Ah, the autobiographical comic. Is there a genre more maligned and misunderstood. Apart from superhero comics I mean.

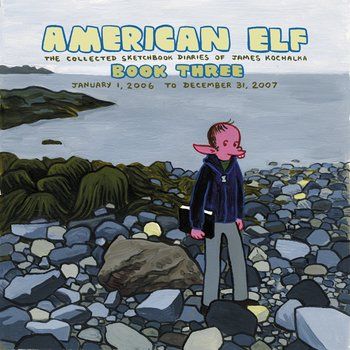

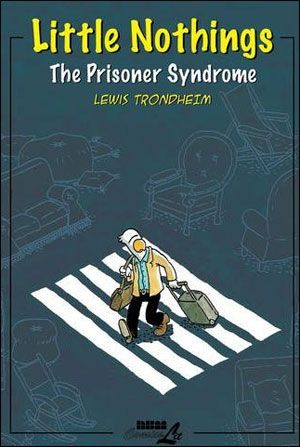

It's a genre that tends to get lumped together as "too much of the same thing," a criticism I really don't agree with. Two recent autobiographical diary comics -- Little Nothings: The Prisoner Syndrome by Lewis Trondheim and American Elf Book Three by James Kochalka -- for example are very similar in execution and style (both are diary comics) but very different in what they reveal and the ways they present themselves to the reader.

As with the first Little Nothings book, The Curse of the Umbrella, The Prisoner Syndrome is filled with the sort of low-key and everday musings that we all have during our daily travails. Each page is a single entry, with the author worrying about wasting toilet paper, congratulating himself on remembering a fan's face (he credits playing Big Brain Academy on the DS with sharpening his memory), freaking out over blowing his nose and battling a mute woman for control of an ATM machine.

And, as readers of the first volume know, it's all done with Tronheim's traditional flair, stunning watercolor work and sharp wit, so that even the most banal musing becomes funy and charming. It's not the event itself that makes the punchline, but Trondheim's reaction, his reflections on the events that plague and delight him that provoke laughter.

The thing that strikes me about the Little Nothings series, though, is ultimately how insular it is. We don't really ever get a sense of what Trondheim's wife and children are like or his relationship to them, nor his friends or fellow cartoonists. The only real extended sequence of family life we get is when the cat dies and we really only see Trondheim's reaction to it. For all the detailed drawings of buildings and towns and cities, Little Nothings takes place primarily in the author's brain.

The picture that Trondheim chooses to present of himself then, is of a slightly superstitious, and slightly obsessive compulsive, but very witty and mischievous man; one perhaps a bit surly but overall far from unlikeable. But it's important to remember how selective this portrait is. At one point his wife chastises him for not telling the entire truth behind an earlier story. "It's one thing for you to depict yourself and make yourself into something you're really not," she says, "but not us." It was moments like that made me realize just how insular Trondheim's world is here and how little he really shows us.

By contrast, Kochalka's diary strips feature his wife, children and friends almost as much as they do Kochalka himself. Whereas Trondheim's musings lean more towards the interior life of the mind, Kochalka's focus more towards the exterior world around him.

That's not to say that Kochalka isn't given to the sort of musings that inhabit Trondheim's book; he is. But easily the bulk of the book is given towards recounting amusing or insightful conversations or anecdotes with those in his inner circle. Kochalka wants to show how he interacts with the world around him as much as how he interprets it.

And whereas Trondhem paints himself as a somewhat cranky but lovable amateur philosopher, Kochalka wants you to see him as a cool, hip guy, not to mention a great dad. I'm not saying, mind you, that the Elf strips are nothing more than a daily form of self-aggrandizement. Kochalka isn't above showing his ugly side and there are plenty of strips that portray him as petulant, annoying or selfish. And Kochalka's outer lying themes and sense of humor is universal enough that readers can take pleasure in the book without worrying about whether the author is trying to sell a portrait of themselves that may or may not be entirely truthful.

Ultimately though, I have no idea how consciously Trondheim and Kochalka are attempting to shape their cartoon personas in these books. Acknowledging those aspects of the books, however, brings their differences into sharper relief, and can even make for a richer and interesting reading experience.

Little Nothings: The Prisoner Syndrome

by Lewis Trondheim

NBM, 128 pages, $14.95.

by James Kochalka

Top Shelf, 192 pages, $19.95.