The Upside-Down World of Gustave Verbeek: The Complete Sunday Comics 1903-1905

Edited by Peter Maresca

Sunday Press Books. 120 pages, $60.

Forever Nuts present: Frederick Burr Opper's Happy Hooligan

Edited by Jeffrey Lindenblatt

NBM, 112 pages, $24.95.

Dread & Superficiality: Woody Allen as a Comic Strip

by Stuart Hample

Abrams, 240 pages, $35

The daily comic strip isn't the only art form to rely upon repetition and formula -- plenty of TV shows and films, not to mention pop songs, do the same -- but certainly a lot of strips, both modern and ancient, trade heavily on familiarity to garner interest and appeal. Beetle Bailey will always be a goldbrick and Sarge will always hector him. Dagwood will always get harassed by his boss and have a sexual fetish for overly large sandwiches. The Family Circus kids will always make cute malapropisms and stay under the age of 10. It's not just the simplicity of the base concept that attracts, it's also the fact that said concept will never, ever alter in any broad, significant fashion that charms readers. Blondie may get a catering job, the Family Circus mom may change her hairstyle, but the core concept remains the same. It's that seemingly endless cycle of repetition and the minute variations that cartoonists attempt to find within that limited scope, that seems to keep (or at least has kept until now) people returning to the funny pages day after day.

Three new comic strip collections underlined for me how integral that feeling of repetition and familiarity has been to the inner workings of the comic strip over the years. (At least as regards the gag strip. Certainly more story-based strips like Terry and the Pirates don't rely on such constant repetition of formula, though certainly you could argue it's present, just to a much lesser degree).

The Upside Down World of Gustave Verbeek brings to light the work of a very early comic strip pioneer; someone who's name and work has been frequently mentioned but -- unless you've got a collection of yellowing newspaper in your closet -- has only been glimpsed at in the occasional Bill Blackbeard anthology.

Verbeek himself has been something of a question mark apparently; little was known about him up till now. The son of Dutch missionaries, he was born and grew up in Japan before emigrating to Paris and later America. As a result of his early travels much in the book is made of the Eastern influence in his work. It certainly is present in his choice of colors and gentle tone, though his work has a decided Western sensibility nevertheless.

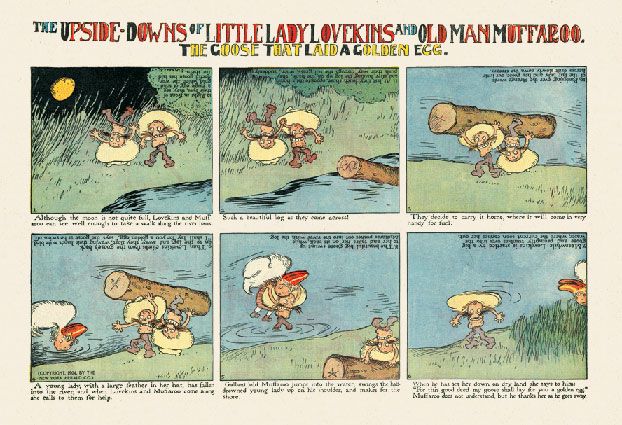

The central focus of the book is Verbeek's most well known(at least today) strip, The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffarooo. This was a Sunday strip where the basic premise lay in the novelty of its design. You first read the story normally, left to right, but then had to turn the paper 180 degrees to get to the conclusion. Turned on their heels, the drawings would take on new shapes: Muffaroo would magically turn into Lovekins and vice versa. Clouds of smoke would become a giant bird. A little old man would turn into a monster. Someone climbing a tree would now be falling, and so on.

That was the basic idea anyway. Oftentimes you really have to stretch your imagination and squint a bit to pretend that the "woman in a big cloak and turban" is actually a woman in a big cloak and turban and not the upside-down chicken it looks like. Little Lady Lovkins' hat never looks makes for a convincing chapeau, but instead resembles an upside down pair of pants flailing in the wind. There are occasional visual surprises, but all too often the upside-down trick is all too obvious, or results in an odd blob that resembles neither thing it's supposed to be.

To ensure the strip's constant turnabout novelty, Verbeek followed a pretty simple premise. Lovekins and Muffaroo go walking, they come across something strange, are assaulted by a creature, and then everything rights itself and they go home. There's no character development to speak of, even compared to other strips from the same time. Narrative comes second to the thrill of formalism. In order to carry the strip's central, formalist conceit, characters, dialogue and extended narrative had to give way to a simple repetitive formula. As a result, the strip's charms -- and the strip is charming, make no mistake -- remain fleeting and ephemeral. As fun as Upside-Down is, shapeless blobs or no, it also remains curiously trapped by its premise.

In addition to Upside-Down, the book also contains samples of other Verbeek work, including Loony Lyrics of Lulu, in which a little girl who thinks up amusing limericks about peculiar animals while her father is routinely attacked by them, and Terror of the Tiny Tads, another "kids strip" that ran for much longer and at the time seems to have been more popular than Upside-Down.

The plot in Tads is just as basic as in Lulu and Downs: a loose group of scraggly youths (tweens initially who regress later to tots) come across a strange creature that's some sort of cross-breed between an actual animal and an inanimate object, like the elephantbrella, that either menaces them or becomes their friend, or, on the rare occasion, becomes their meal. Again, as in Upside-Down, the basic conceit is enough for Verbeek to repeat ad infitum, with little variation.

Like most Sunday Press books, this is a lavish affair, printed at the original newspaper size and featuring several essays as well as illustration material Verbeek did for magazines, advertisements and other outlets. The end result is a handsome, high-quality book that will be of great interest to comics scholars both amateur and professional, but will probably not have much of an audience beyond that.

Contrast Verbeek's high-minded, storybook fantasy with that of Frederick Burr Opper's Happy Hooligan. The premise is even more of a fixed constant than in Upside-Down. To wit: Happy attempts to help somebody, say by aiding them in taking off their coat or covering a puddle for a passing lady, only to have it all go horribly, horribly wrong, to the point where even the person he tried to help is smacking him over the head and declaring him to be the most horrible person alive. And then the cops come and drag him away to jail.

This happens every single time, without fail. He can be in the U.S. or England, with friends or alone, I think there are one or two instances where he manages to escape capture or his gloomy cousin ends up bearing the brunt of the assault, but those are really the exceptions that prove the rule.

This was the sort of lowbrow humor that the middle classes at the time allegedly frowned upon, preferring more wholesome antics like Verbeek's. Certainly Hooligan, with his Brooklyn accent, precarious tin-can hat and ragged clothing was both a parody and symbol of the new, downtrodden immigrant. Perhaps that identification was part of the strip's appeal though early 20th century readers probably just enjoyed watching him get hit on the head repeatedly.

Of course, then there's the fact that Hopper was an agile, clever cartoonist, who knew how to milk a formula for maximum effect. There's an immediate, visceral delight to these Hooligan strips and that not a lot of strips from that era can match. Verbeek's strips have charm, but they merely amuse, whereas Hooligan's antics are genuinely funny.

But compare, if you will, Hooligan's slapstick comic strip shenanigans with that of Woody Allen. Yes, that Woody Allen. Believe it or not, but he had a comic strip that ran in newspapers from 1976 to 1984, and has now been collected in a rather hefty coffee table book entitled Dread and Superficiality.

Allen honestly didn't have much to do with the strip, it was the brainchild of one Stuart Hample, an illustrator and cartoonist who knew Allen back in his early, bitter years of struggle, and suggested the idea to him years later when Hample was desperate to get out of his nine to five job.

Like Hooligan and Upside Down, Inside Woody Allen as it was known, follows a pretty rigid formula. Here, though, said formula is almost entirely verbal, emblematic of the changes wrought upon the funnies pages in the ensuing century, where a greater reliance on "intellectual humor," a smaller reliance on artistic craft due to the ever-shrinking space on the comics page, forced cartoonists to simplify.

Hample is a decent enough cartoonist, with a nice, big-nose, big-foot style (think Mel Lazarus with a bit more craft) but he doesn't do anything with his art. The drawings -- most of them spartan in design -- are all secondary to the jokes, which often read like a stand-up routine. Compare that to Hooligan or Upside, where detail crowds the page and everything is in constant motion (with Verbeek it's a lyrical motion, but still).

The strip basically reflects the "early" version of Allen. It's Woody the put-upon schlemiel, the nebbishy loser. It's an image that was starting to wane even in the years this strip was running, as Allen attempted to shed that persona in films like Stardust Memories and Interiors. (Considering that eight years after the strip ended the comedian's image would be tarnished by his scandal with Mia Farrow and her stepdaughter, one would say it came to a close just in time).

In the forward, Hample notes that Allen constantly sent him suggestions, urging him to push the strip in interesting directions, try extended storylines, add more characters, and generally not be afraid to push the envelope. Hample, however, was facing opposite pressure from the syndicate, who wanted a safe strip that played on Allen's familiar qualities but would still be acceptable in America's heartland. Looking over this book, it's easy to see which side won out. Inside Woody Allen is a fitfully amusing, but ultimately bland strip that never varies from its gag-a-day formula. Here is one instance where the insistance upon repitition resulted in rote material.