Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

By Roz Chast

In Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? Roz Chast has produced an amazingly honest and clear-eyed memoir of her relationship with her parents in their declining years. It's both a universal story of something many of us will go through and a very particular account of a single family of quirky individuals.

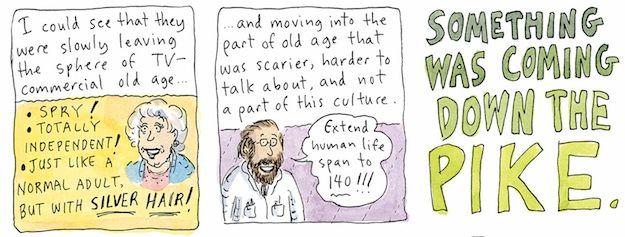

Chast had an unusual upbringing: She was an only child (a sister died at birth 14 years before she was born), and her parents had her late in life, so she always felt like a bit of an interloper. Her mother had a domineering personality and a sharp temper — she described her own outbursts as "A blast from Chast." Her father was quieter, easier to get along with, but also plagued by anxieties and phobias, which led him to rely completely on her mother. They were, as Chast describes them, "a tight little unit," and they seemed to believe that if they carefully avoided the subject of future unpleasantness, nothing would change. She depicts this perfectly in a single panel in which the hooded figure of Death roars "What's THIS??? The Chasts are talking about me! Why, I'll show THEM!!!"

And that right there is what makes this graphic novel stand out: Chast doesn't flinch from the serious stuff, be it her difficult relationship with her mother or the indignities of age and illness, but she tells her story with a strong dose of humor.

The other thing that makes the book so fascinating is that it's solidly grounded in her family's everyday life, embracing the pedestrian and the terrifying in a single set of images. Chast's parents have their little ways — her mother writes poetry, her father has to cut up his food just so, they have a million little bank accounts they opened to get a free blender or toaster. These are all part of the narrative, as much as their progressive illnesses and health scares, and in fact the two are often intertwined — Chast's father's agitation about the bankbooks is a sign of his increasing dementia, for instance. At one point, after Chast moves her parents out of their apartment, she photographs the belongings they left behind. It's strangely poignant to see the everyday objects of their life, once fresh and new, now old and shabby (not retro — just old), spread out in rooms that once buzzed with life. There's another moment, right after her father's death, where the family goes home and has pizza. "It felt surreal: I'm eating pizza. My father just died. Do you want another slice?" For those of us who were fortunate not to have had a lot of illness and death in our lives until our parents began their decline, that's one of the jarring things about this period: The juxtaposition of everyday life with death and dying, the way you go from the sickroom to the supermarket, from your father's deathbed to your kitchen counter.

Although this book is in graphic novel format, Chast doesn't tell her story in a single continuous stream of panels. It's broken up into little episodes, some told as single-page comics, some as images with text, and occasionally, as when she gathers the cautionary tales told by her father into "The Wheel of Doom," she fills the page with a single image. Breaking up the story this way allows her to vary the mood—from serious to funny and back again—and also keeps it from feeling like a long slog, the way a story like this might. In fact, that's how caring for elders often goes, in fits and starts, and in this way, art is imitating life.

As someone who has lived through this set of experiences, I could relate to a lot of what Chast wrote, and I appreciated her bluntness and her humor. The realities of illness and death are hard, but there are moments of grace and laughter as well. It could be depressing: Chast never resolves her unhappy relationship with her mother before she dies, and the details of aging are not for the faint of heart. But it's not, and not just because Chast can make a joke in any crisis; it's because she acknowledges the pain and moves forward anyway. This is a book with a lot to say, both to those of us who have already been through this journey and those for whom it lies ahead.

There's a good-sized preview at the New Yorker site, and Alex Dueben interviewed Chast at CBR.