Failure (Alternative Comics): Faithful readers of ROBOT 6 may recall the name of cartoonist Karl Stevens from a fall 2012 story about his Boston Phoenix strip Failure being canceled after an installment referred to Bud Light -- one of the paper's advertisers -- as "diluted horse piss." The Phoenix denied this at the time, and, coincidentally, several months later ceased publication all together (after a brief time in which it was split into five different newspapers with five different editors — Cyclops, Emma Frost, Namor, Colossus and Magik — until Cyclops assumed control over all five papers and it took the combined might of all of the Avengers to stop him ... there's a comic book joke for you!).

While that history may not be particularly relevant to readers, Stevens covers his side of the incident in his introduction to the Failure collection, which packages the final installments of his strip — right up to, and a few past, the "horse piss" one — into 150 pages of gorgeously drawn material.

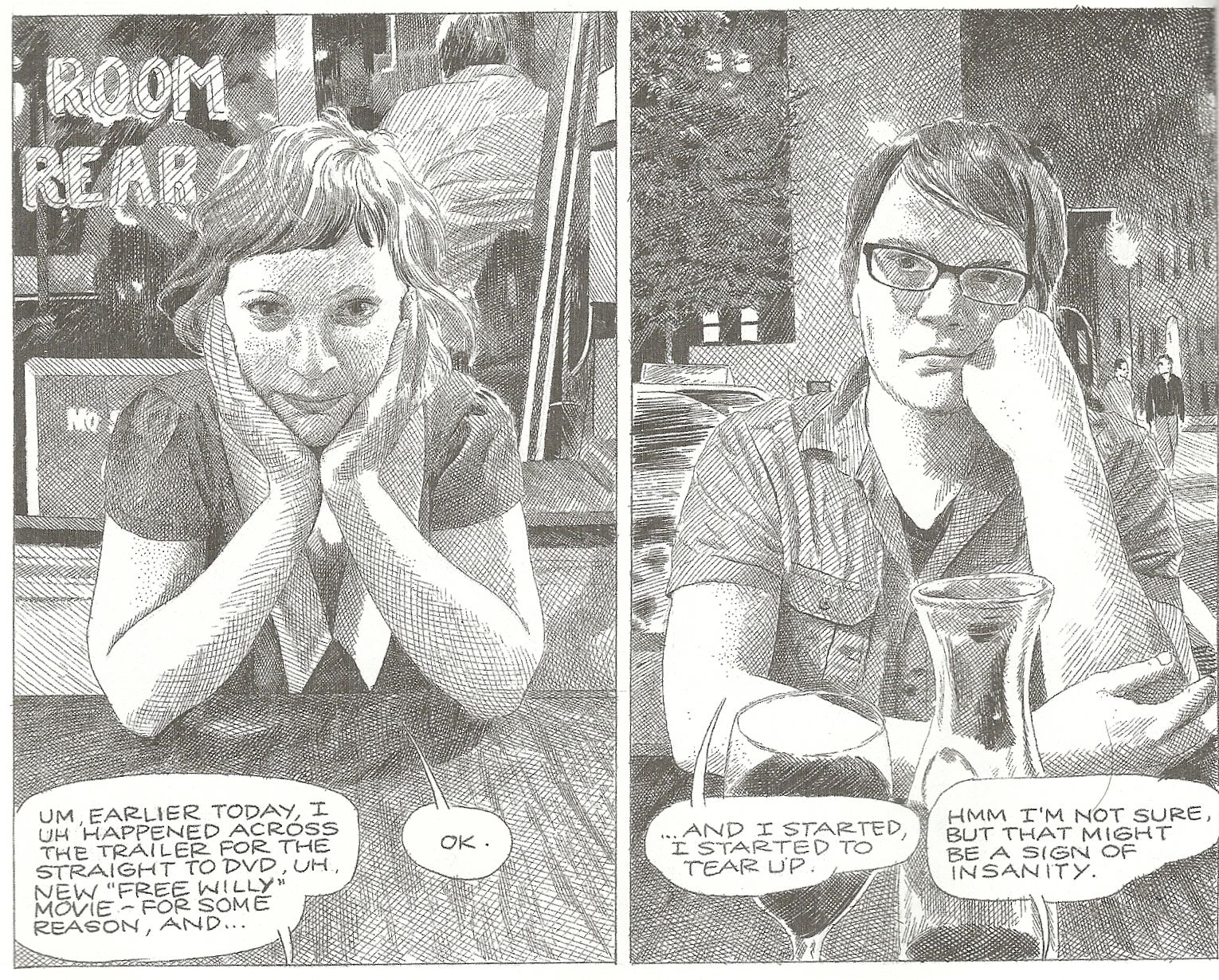

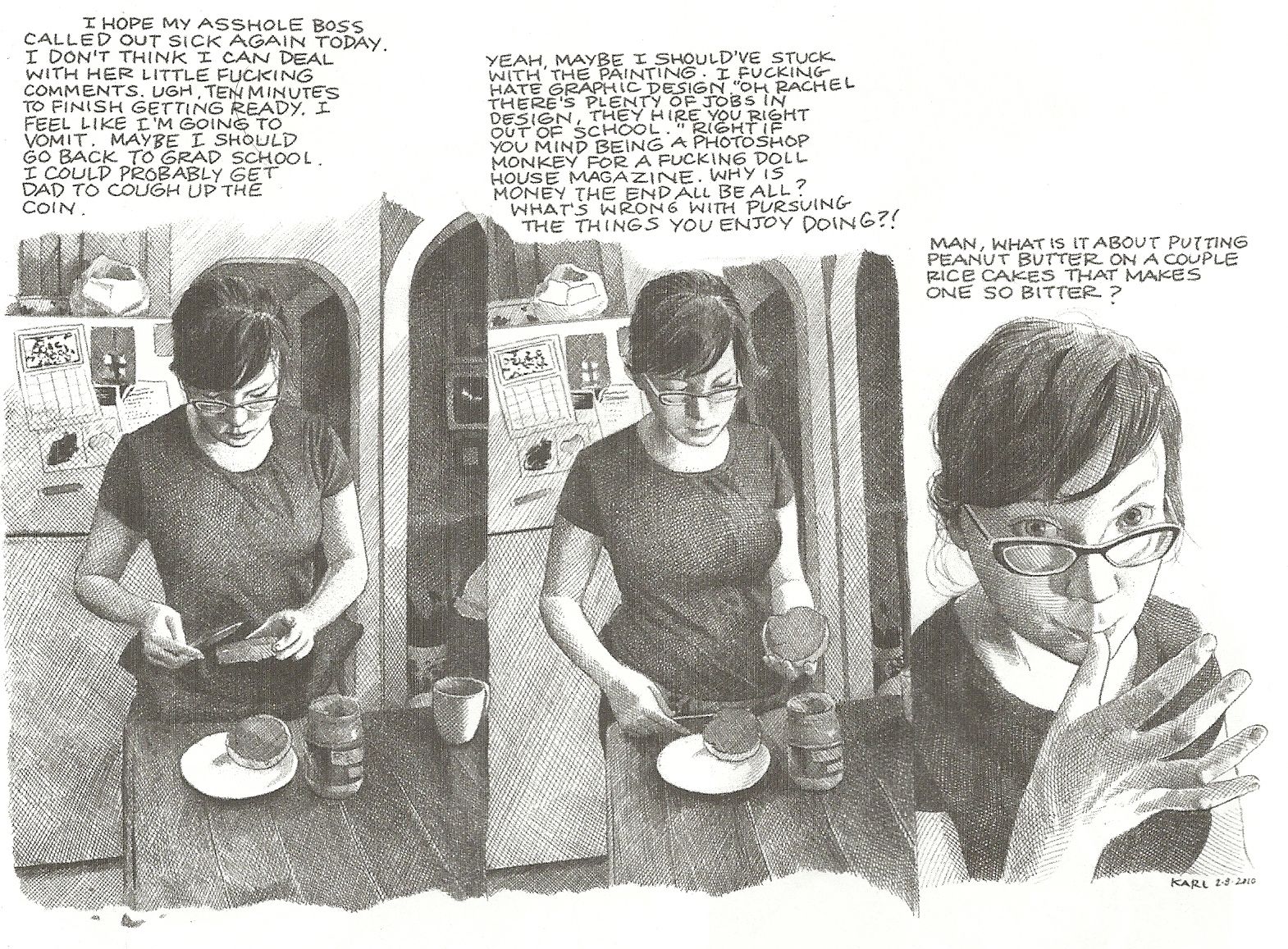

What is important is that this is some great work, of the must-read variety. Failure, at this point in its existence, had become a sort of slice-of-life strip, with one to four panels devoted to anecdotes from his own life, including his relationship with his girlfriend, funny things his friends said or funny things he overheard. There are, additionally, plenty of flights of fancy starring his descendant in the far-flung future, and recurring characters like Bongbot, a time-traveling robot bong, and Pope Cat, a cat who is also the pope (if I've got that right).

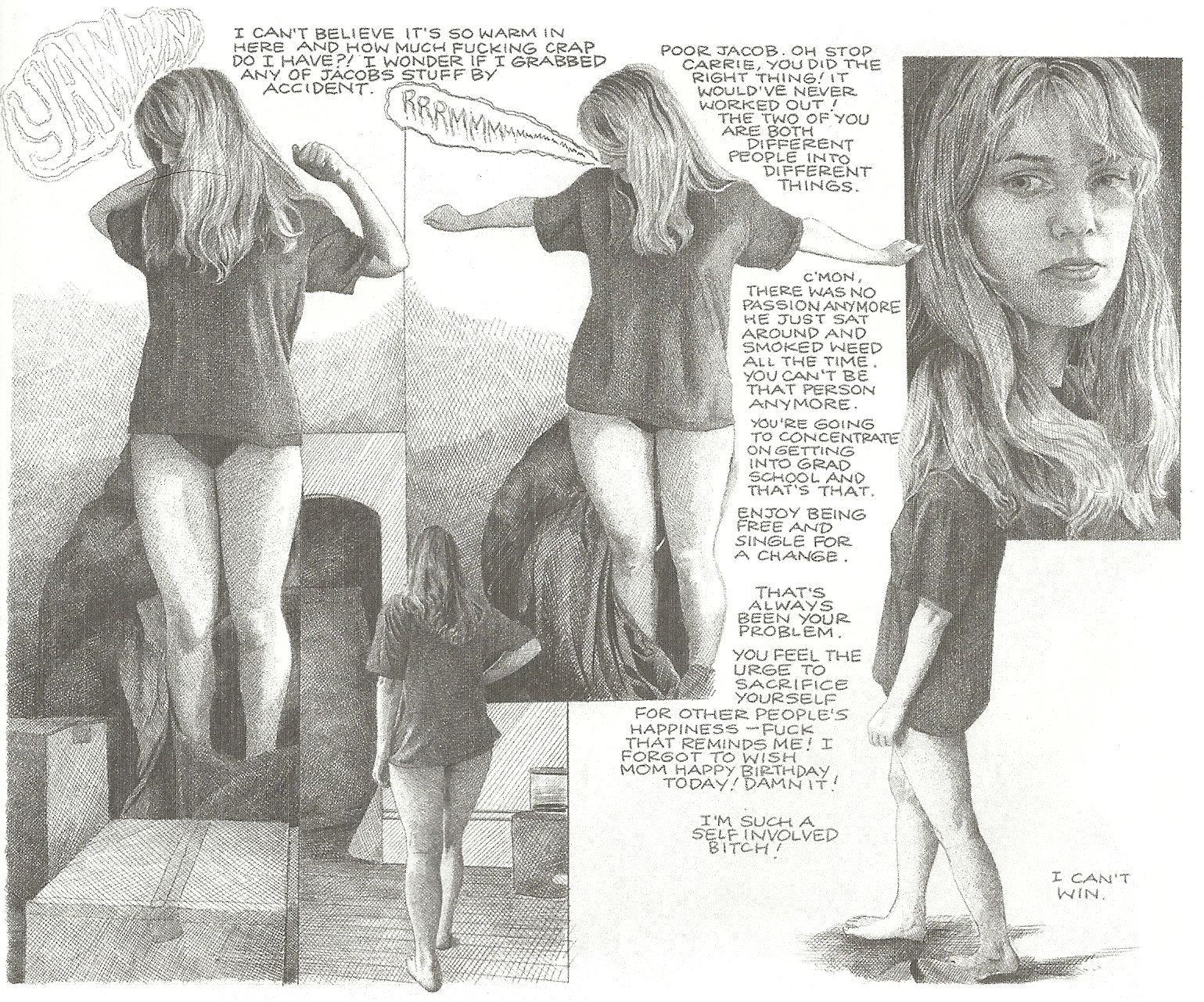

What keeps Failure from being as mundane as you might imagine it, based on how I just described its premise, is what an incredible artist Stevens is. He works in a lush, highly detailed, representational style, as if he were drawing portraits rather than cartoons. Check this out:

That's some real Leonardo da Vinci-looking shit, isn't it?

Stevens actually draws in several styles throughout the book, with some pieces in full color, some in that delicately cross-hatched black and white, some in a rougher, more comic book-y style, a few more sketched than drawn, with the lines for spacing out the lettering still visible. There are even a few strips aping of the styles of Jim Davis and Bil Keane

It's pretty appropriate given the general subject matter— the life of a young, hip, urban, creative class-er and the city around him — and while those who dwell in that city will likely get the absolute most out of the strips, as they'll recognize the backgrounds and names of bars and restaurants referenced, the experiences are universal enough that this isn't for locals-only or anything.

As I finished reading it, I had two thoughts that wouldn't leave me. First, Karl Stevens has got some serious drawing chops. And second, Bostonians used to get this stuff for free every single week? Stupid, lucky, spoiled Bostonians...

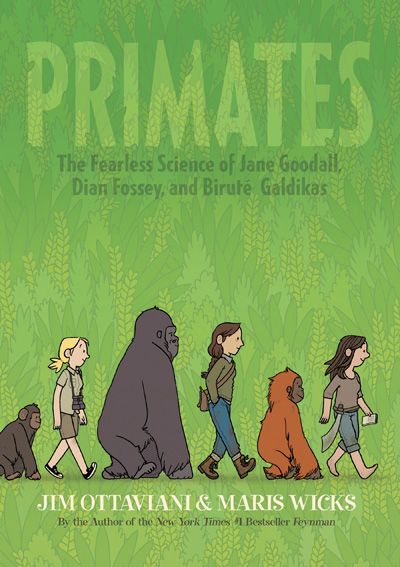

Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Diane Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas (First Second): Jim Ottaviani -- who is perhaps best known for Two-Fisted Science or Feynman, but whose Bonesharps, Cowboys and Thunder Lizards remains my favorite of his works — teams with artist Maris Wicks to tell the amazing story of a three amazing women who revolutionized our understanding of our fellow primates through a combination of patience, endurance and courage.

All three share a lot in common, aside from their gender, their accomplishments and that they each studied a specific group of primates (Goodall chimpanzees, Fossey gorillas and Galdikas orangutans). They also all got their starts from Louis Leakey, who believed women had the patience and attention to detail that field research required in greater abundance than men.

Ottaviani uses these commonalities, and Leakey's presence in each of their lives, to braid their biographies together, but each woman was very different from one another, and their stories even more so. Their individual characters are therefore all the more starkly drawn by appearing side by side within the same volume.

Wicks' simple, cartoony art and its bright, warm coloring makes for a graphic novel with a broad appeal, and the stripped-down design elements serve to define the characters by calling attention to how much they visually have in common and what visual quirks differentiate them and, whether intentionally or not, demonstrating how similar humanity is to the other primates (Human or chimp or orangutan, we've all got little black dots for eyes, for example).

Simple isn't the same thing as simplistic, of course, and as minimalistic as aspects of Wicks' art can be, she is an incredible cartoon "actor," and the range of behaviors and emotions she's able to summon in the characters — particularly the animal ones — is pretty astounding.

This is one of those too-rare books where it's easy to recommend it to just about anyone, and hard to imagine anyone who wouldn't like it.

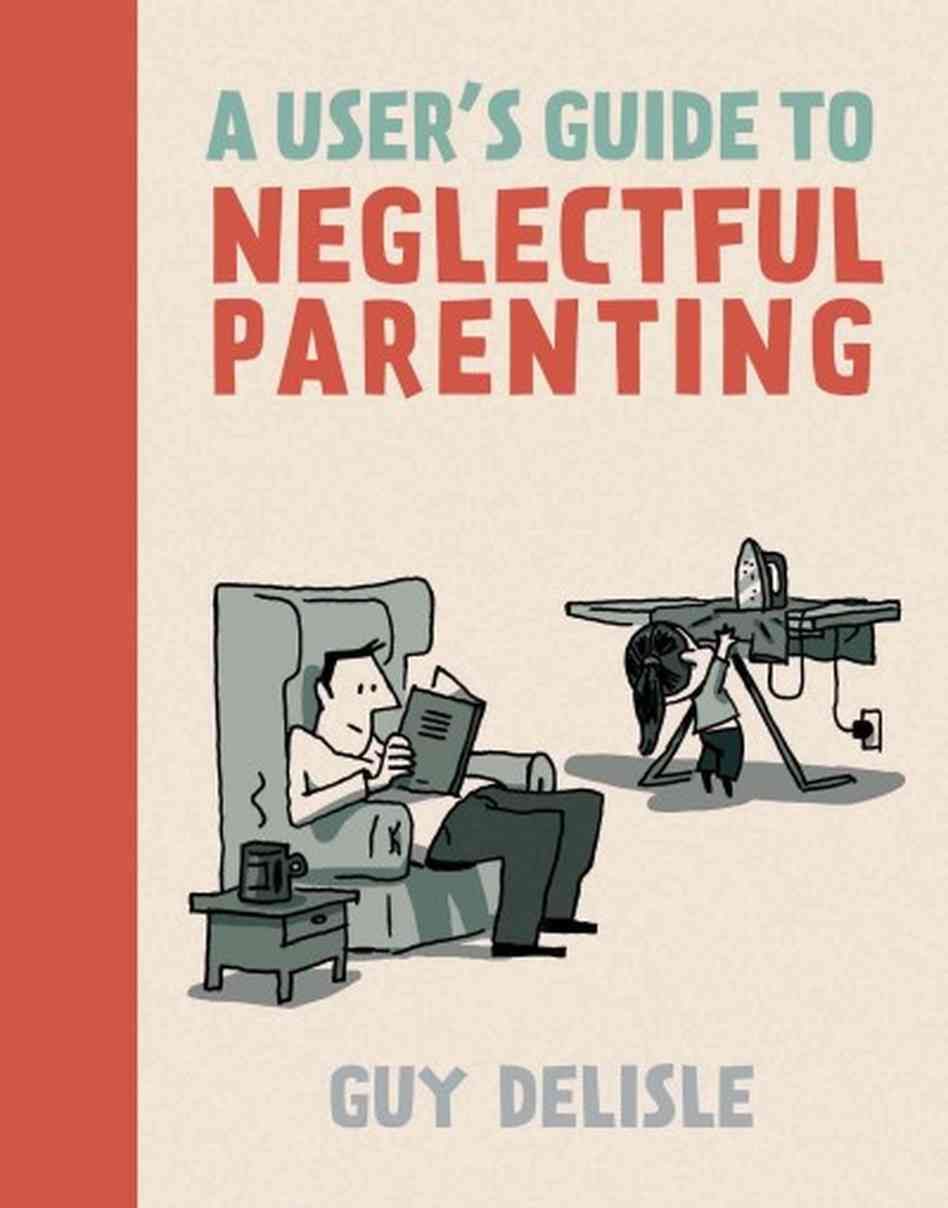

A User's Guide to Neglectful Parenting (Drawn and Quarterly): What's this? Guy Delisle, just sitting around at home? Yes, this delightful little book by the cartoonist best known for his sharply observed, extremely relevant graphic novel travelogues of time spent in some of the hardest/least desirable places to visit (Shenzhen, Pyognyang, Jerusalem and The Burma Chronicles) is nothing but short, funny stories about Delisle (or his cartoon avatar, anyway) interacting with his two young children.

The subject matter is pretty different, at least as organizing principle, and so too is the format: There are hardly any backgrounds here, and the "panels" are all implied ones, with about two images per page, the stories stretching out to as many as 20 pages or so.

The art style is certainly familiar, however, and it's a treat to see Delisle's art so big and with so much room to breathe, as its given here, allowing a reader to better appreciate his line work and his mastery of the simple mechanics of telling a story through comics.

As the title implies, these are mostly stories of the author/author's avatar being a less-than-perfect father, as when he tries to keep a straight face while talking about the Easter Bunny, or repeatedly forgets to play the Tooth Fairy, or accidentally has a frank discussion of sex when his son asks about something in the context of a Zelda video game, or looks over a drawing his daughter made for him and replies, "I'm gonna tell you straight out, you're not bringing home an Eisner with this stuff."

It's a quick — probably too quick, honestly — read, but then I've yet to read a Delisle comic that I didn' t wish were longer than it was.

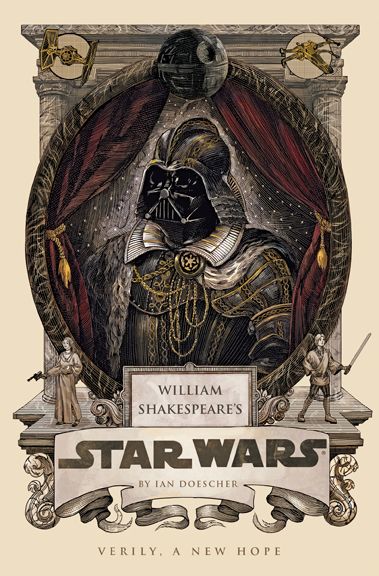

William Shakespeare's Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope (Quirk Books): This is not — I repeat, not — a comic book, a graphic novel or an example of sequential art by any stretch of the imagination, but I'm going to go ahead and cover it here anyway because a) an awful lot of you fall into the shared space on a Venn diagram of People Who Read This Blog and People Who Like Star Wars, b) at this point, the Star Wars characters are as much — if not more — comic book characters than they are film characters, regardless of what the original medium they emerged from was, and c) I want to.

The premise of this slim hardcover volume, which is actually the work of one Ian Doescher rather than Bill Shakespeare, is as simple to explain as it must have been difficult to execute: What if the script for the original Star Wars movie were re-written and presented as one of Shakespeare's plays?

There's an afterword in which Doescher talks a bit about the similarities between certain characters of George Lucas' creation and those of Shakespeare's creation, and that Lucas studied Joseph Campbell, who studied Shakespeare, but it basically boils down to the fact that it would be kind of funny to see Star Wars reimagined thusly, complete with R2D2's beeping and Chewbacca's roaring in iambic pentameter, and stage directions for a production.

Doeeschler certainly pulls it off to a remarkable degree, finding equivalencies between certain characters and lines of dialogue, with C3PO serving as lowly comedy relief, for example, and R2D2 given lengthy English speeches made in aside, while he plays the foolish, beeping droid, not unlike King Lear feigning madness. There are some more obvious bits where the parallels aren't just suggested, but over-emphasized to a groaning degree ("What light through yonder flashing sensor breaks?" for example, or "A plague on both our circuit boards" or "Friends, rebels, starfighters, lend me your ears")

As impressive an accomplishment as Doescher's book is, I think to a general audience, it's a funny idea, and reading all the way through it doesn't necessarily make it any funnier than simply hearing about it. For Star Wars fans, there's certainly the curiosity factor, of wondering how a particularly well-known line might be Shakespeare-ized ("'Tis but the ship that hath the Kessel run/ Accomplish'd in twelve parsecs, nothing more," for example).

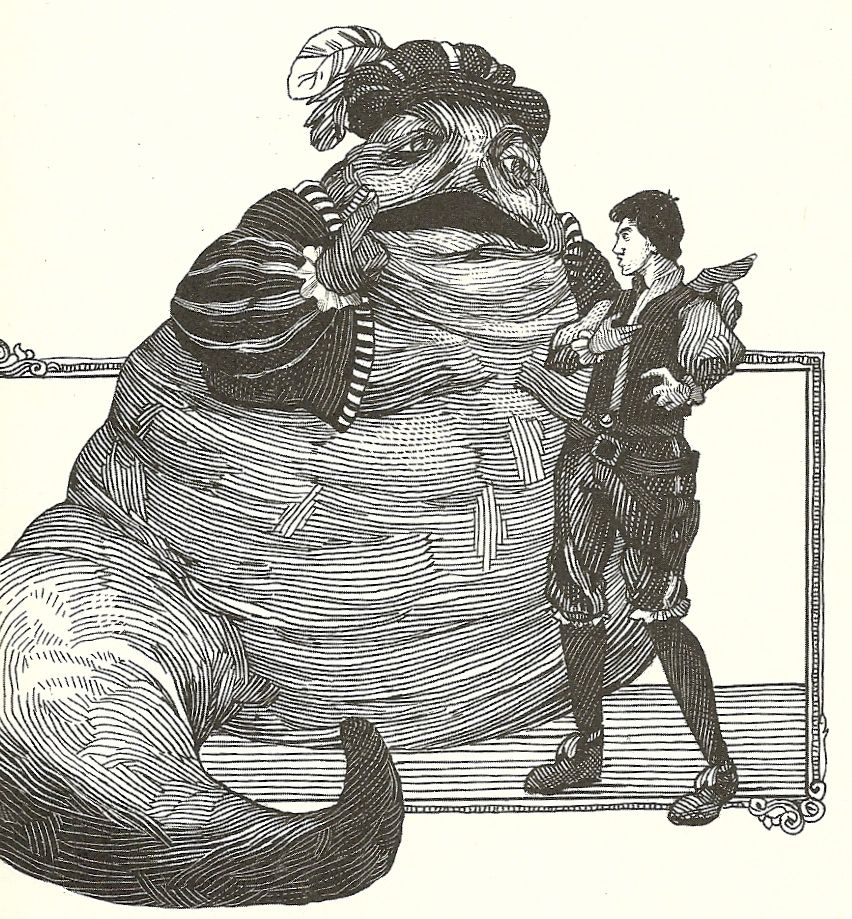

My favorite part was probably illustrator Nicolas Delort's drawing of Jabba the Hutt wearing a cap and jacket ...

... although I quite appreciated the way in which Doescher dealt with the discrepancy between the original film's portrayal of the Han Solo/Greedo scene and the later version. The stage directions say merely "They shoot, Greedo dies."

And the scene ends with these lines from Han:

[To inkeeper:] Pray, goodly Sir, forgive me for the mess.

[Aside:] And whether I shot first, I'll ne'er confess!