"You're wondering who I am - machine or mannequin"

Sydney Padua's charming comic about Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace is a hulking slab of a book, 317 pages stuffed with cartoons and text, which is why Pantheon Books priced it at $28.95. But who cares about price when you're reading such an educational and entertaining (an "edutational," if you will) comic? No one!

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage is not exactly a dual biography - Padua takes care of the basics of their lives in the first 28 pages (plus the voluminous, glorious endnotes, which take up another 7 pages) - but a comic about their adventures in a "pocket universe" where Babbage actually built his "analytical engine" - the world's first computer - and Lovelace was able to "program" it, and then the two of them encountered all sorts of fascinating Victorian characters, including the queen herself, Marian Evans (otherwise known as George Eliot), and Charles Dodgson. Through that fun conceit, Padua is able to dive even further into Babbage's "invention" (he never actually built the Analytical Engine) and Lovelace's contributions to it, as well as giving Lovelace a happier ending than she got in real life (she died of cancer when she was 36). That also allows her to have a lot of fun with the characters, and the book is very humorous as well as being educational. That's always cool, right?

If you don't know who Charles Babbage or Augusta Ada Gordon was, this is the book for you. Babbage is probably better known - today he's regarded as the father of computers - but Ada (calling her "Ada Lovelace" is incorrect, as Padua points out, because she was technically married to William King, who later became the Earl of Lovelace, making her a countess, but everyone apparently called her "Ada Lovelace," so whatever) should probably be as famous, especially considering that she was Byron's daughter.

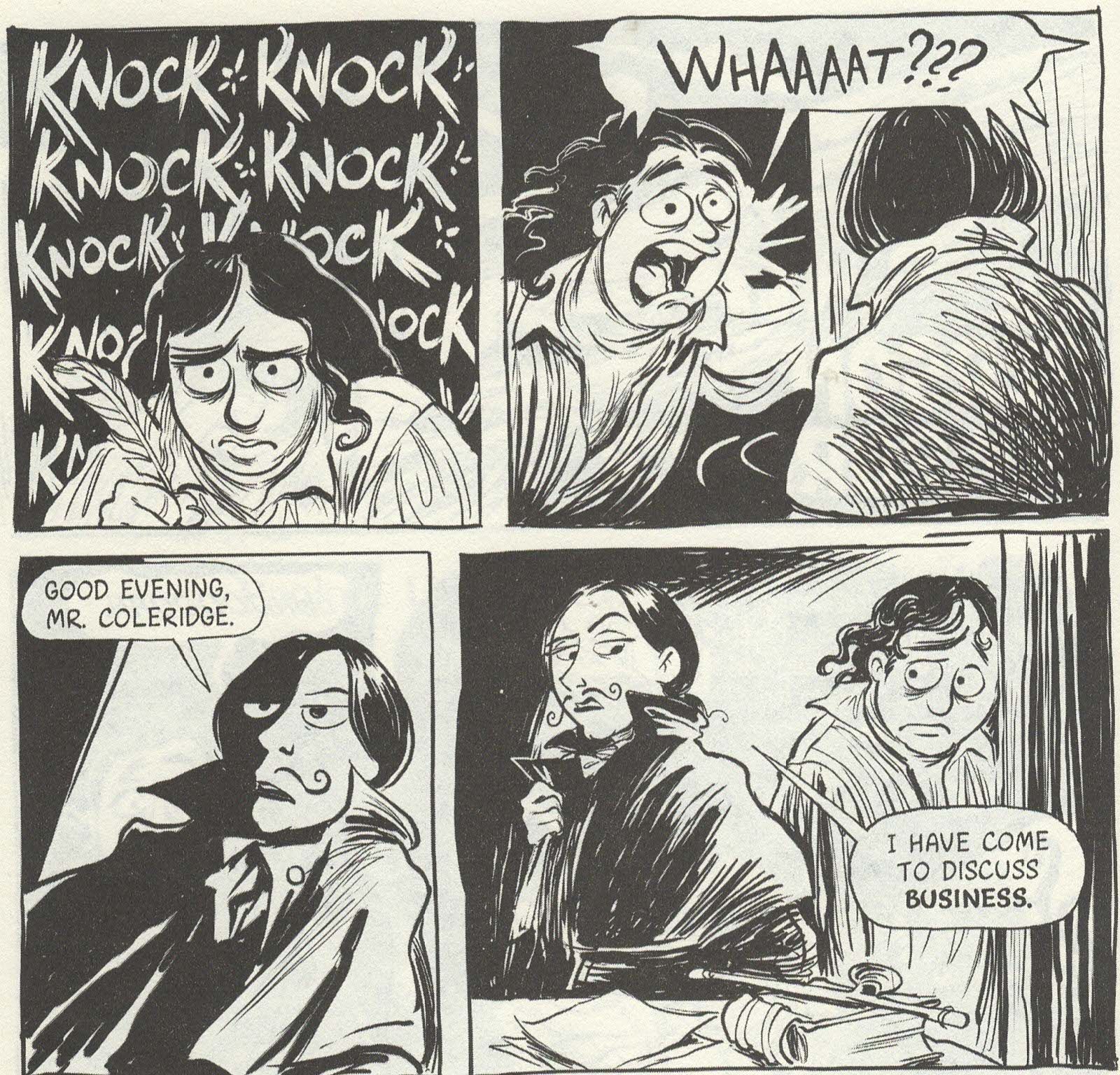

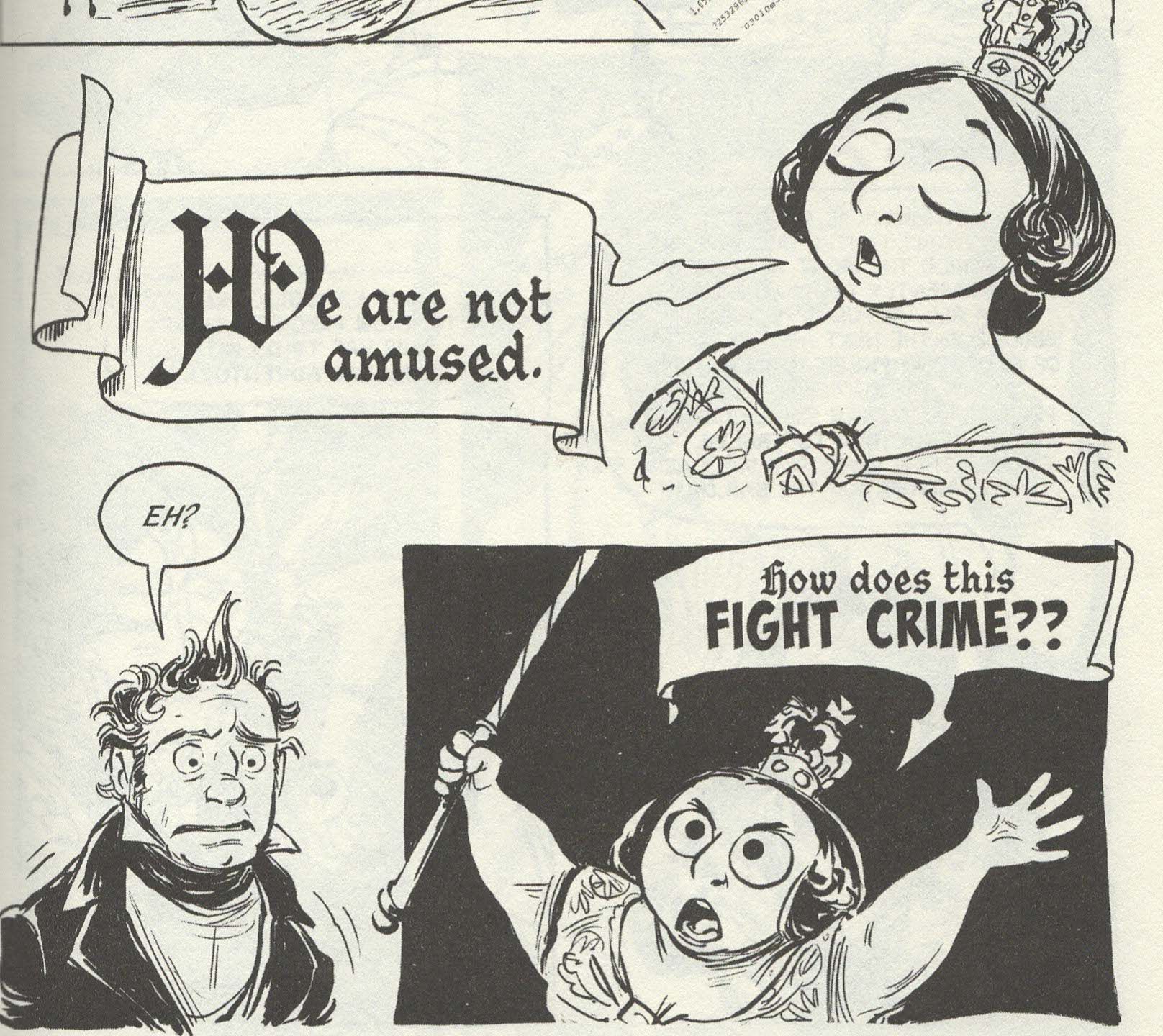

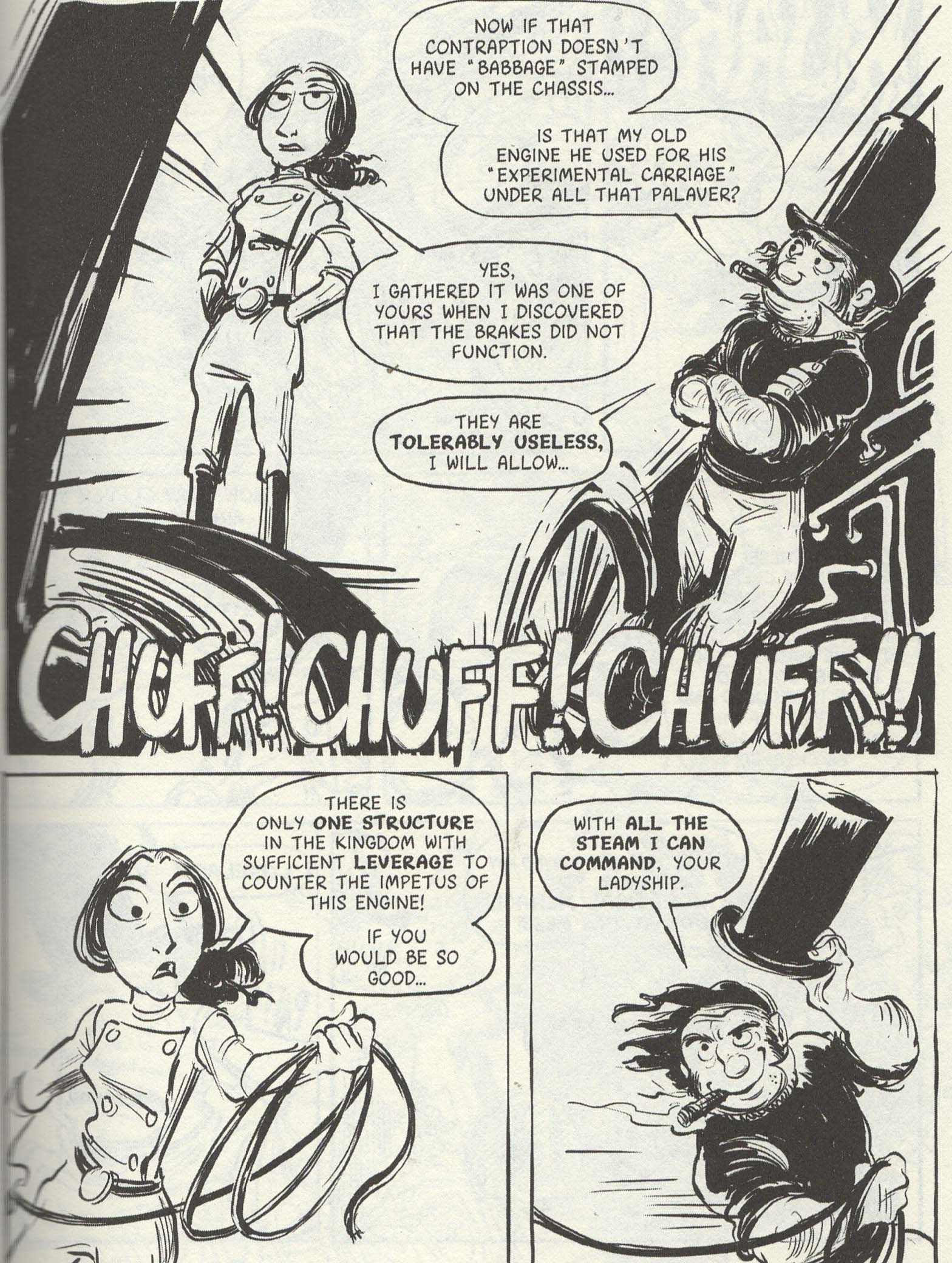

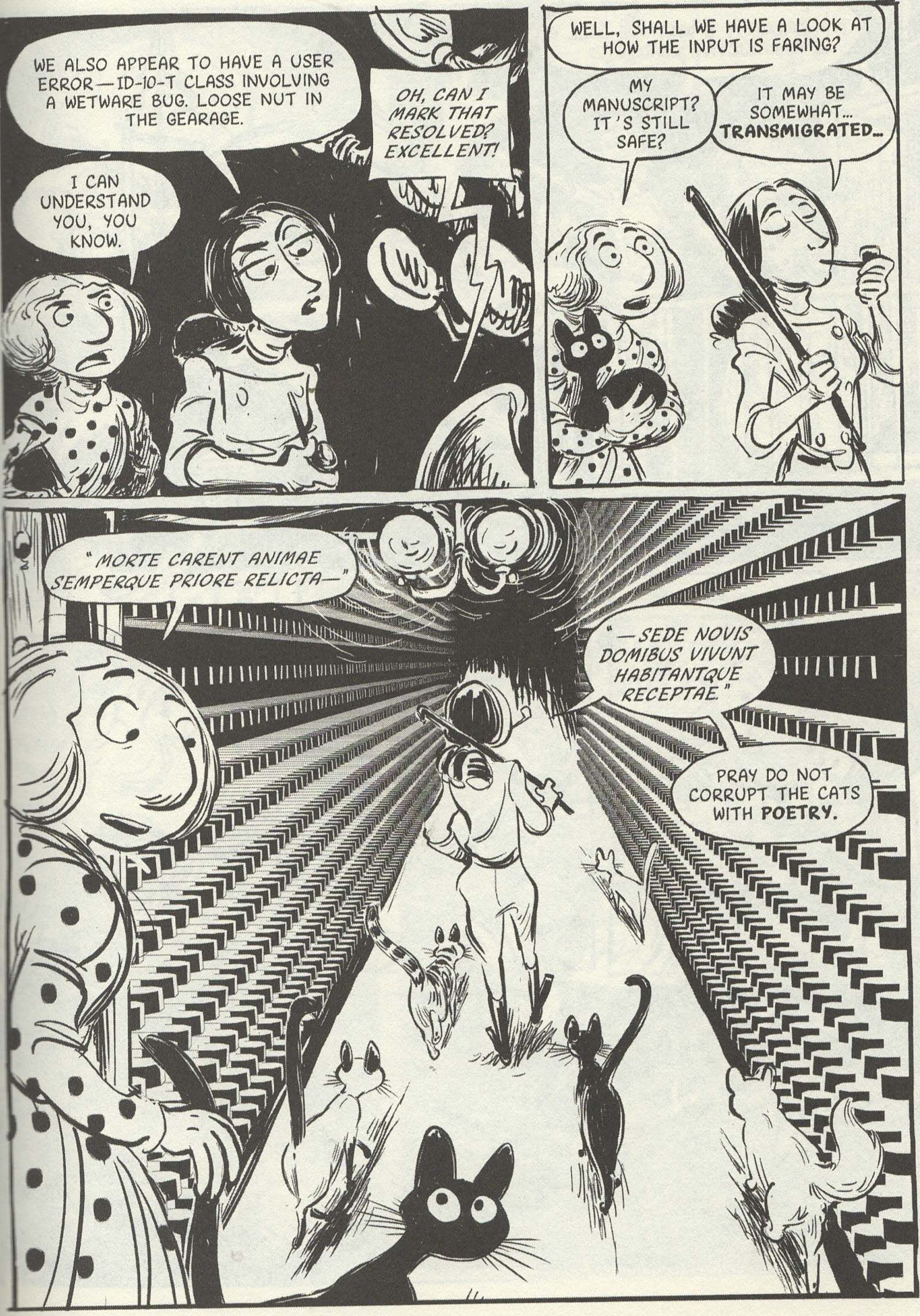

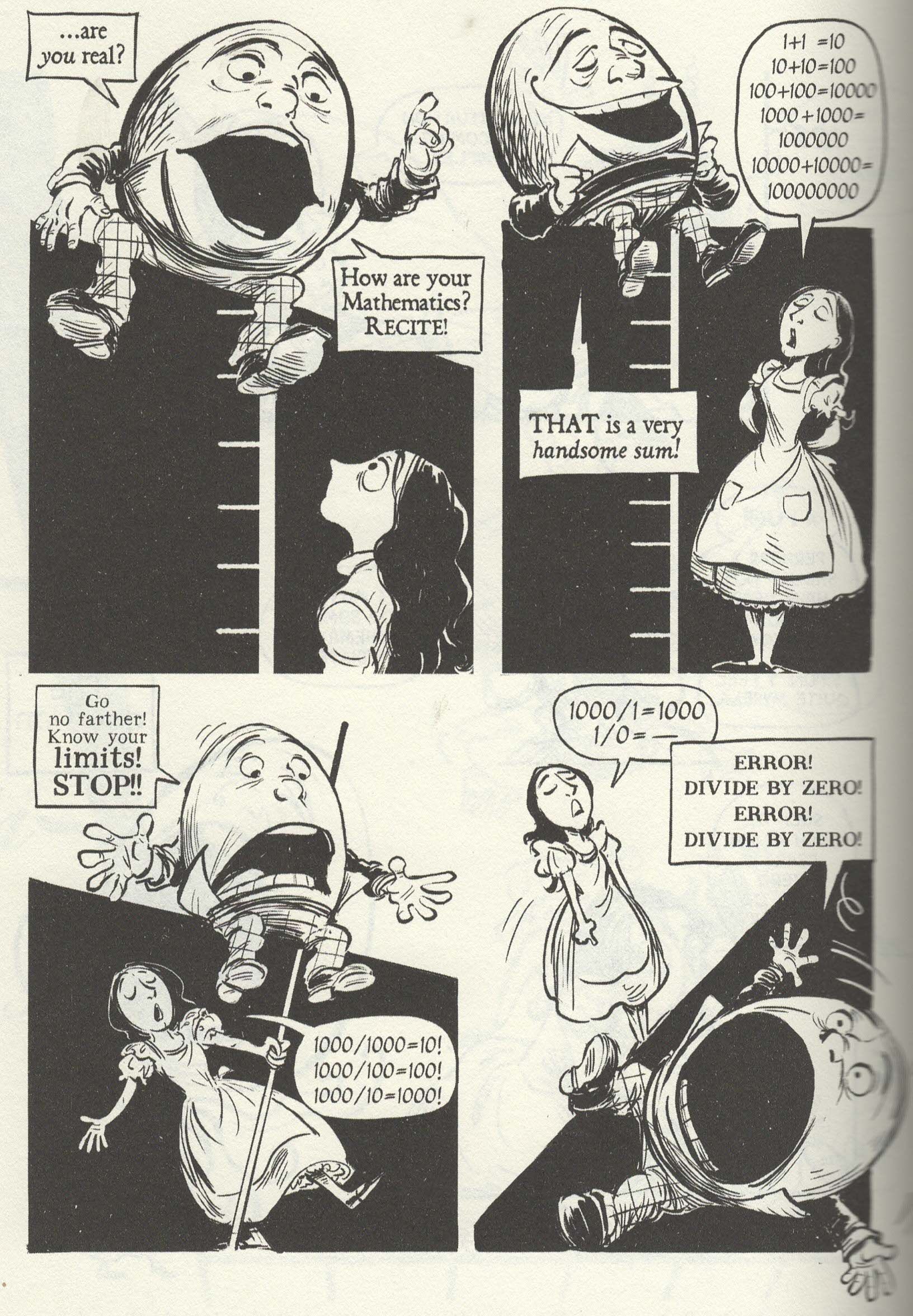

Padua introduces the two of them and sketches out how they knew each other - they probably met at a dinner party when Ada was around 18, and she was already well-versed in mathematics due to her mother's insistence that she have nothing to do with poetry, because she feared that Byron's madness would infect their daughter if Ada was too "poetical" - before positing a world where Babbage, who only drew up plans for a "difference engine" and "analytical engine" but built neither of them, actually built them. This transforms Victorian England, obviously - a steampunk computer will do that - and Lovelace and Babbage become celebrities. Padua writes several vignettes about their adventures, from Lovelace deliberately destroying Samuel Taylor Coleridge's writing of "Kubla Khan" (which Padua argues, convincingly, that she may have done in "real life") to Babbage saving the English banking system during the Panic of 1837. The very young Queen Victoria shows up to find out what Babbage's machine can do and leaves satisfied (it involves kittens); Isambard Kingdom Brunel shows up as a hard-smoking, dashing, rough-and-tumble rogue; Marian Evans wanders into the Analytical Engine when Babbage feeds her first manuscript into it so it can be "corrected," orthographically; and Lovelace tries to marry mathematics to poetry, gets caught up in imaginary numbers and Wonderland (spurred on, no doubt, by the impending visit of Dodgson), where she encounters some very sad dimensions.

Padua is a good enough writer that when Lovelace seems to come across her "real life" counterpart, it's kind of a gut punch - we know Lovelace died young and didn't live a particularly happy life, but through all the adventures she and Babbage are having, we kind of forget it until Padua briefly revisits it. It's very nicely done. It's not a depressing book by any means (and, I mean, Lovelace has been dead for 160 years, so it's not like her fate is too sad), but Padua is clever enough to remind us that despite her accomplishments, Ada was still a woman in Victorian England, so her lot in life wasn't great.

While the adventures of the two are funny and clever, Padua takes the time to give us plenty of factual information about the principals and the computer. Whenever a historical figure shows up, we get extensive footnotes AND endnotes (seriously, it's glorious) about them, and she goes into great detail about how Babbage's Analytical Engine and Lovelace's programming would have worked had it been built. Even the footnotes are funny, as Queen Victoria interrupts a particularly long one at one point, Evans is happy there aren't any on one page, and a few times they're written on the top of the page because we have to read the book by turning it over.

So we not only get some fun comics, but the book will tell you any number of things about great Victorian figures and allow Padua to have some fun with them (she reserves a lot of her gentle teasing for Carl Gauss, who wasn't a Victorian figure but who was nevertheless a genius; Padua claims that he didn't publish a lot of what he came up with because he didn't want to take credit for everything in mathematics). She also adds appendices, the first of which she uses to show many letters either written by or concerning our protagonists and the second of which she uses to explain how Babbage's Analytical Engine would have worked. She tackles the controversy over Lovelace - many people think she contributed nothing to Babbage's theories and was simply a scatter-brained young lady that he befriended and then bounced ideas off - and, while she can't say with total conviction that they're wrong, she does show that she was far more than that. She also quotes a terrific letter from Lovelace's tutor to Lovelace's mother on the danger of teaching mathematics to women:

[T]he very great tension of mind which they require is beyond the strength of a woman's physical power of application. Lady L. has unquestionably as much power as would require all the strength of a man's constitution to bear the fatigue of thought to which it will unquestionably lead her. It is very well now, when the subject has not entirely engrossed her attention; by-and-bye when, as always happens, the whole of the thoughts are continually and entirely concentrated upon them, the struggle between the mind and body will begin.

What a charming fellow!

Padua's cartoonish art fits the somewhat light tone of the book - the few times it gets dark, she uses thicker inks on Lovelace's hair, turns it loose so that it flows over her head instead of staying in a relatively neat bun, and underlines her eyes just enough to show her fractured state of mind (she may have inherited some of Byron's "madness" after all).

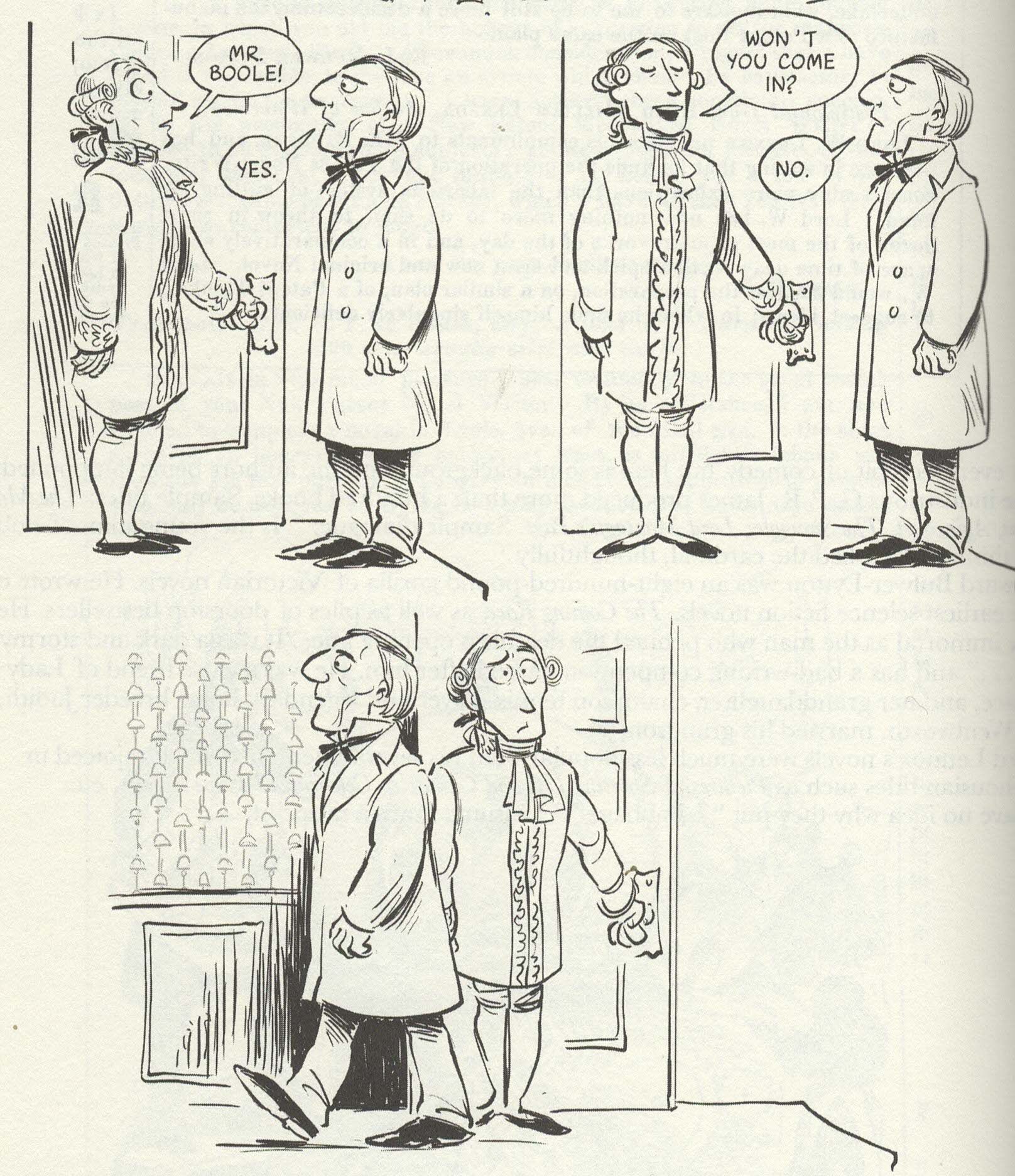

For the most part, Padua has fun with the artwork - Lovelace and Babbage always have a slight mad look on their faces, as they love doing what they're doing so much, and Padua gives Lovelace a pipe in some stories, so she looks even more composed and rational (which makes it funnier when she rants to Babbage or anyone else). The artwork seems to work well in a Victorian setting - it's exaggerated, but thanks to the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites, I (at least) have a vision of the Victorians as snapping at any moment; they might act all cool and collected, but any break in the edifice makes them rage or celebrate excessively, and Padua does this wonderfully with not only her protagonists but the many other characters who wander through the book (Coleridge is angry that his poetry-writing is being interrupted; Queen Victoria wants to take over the world - which Padua points out she kind of did; Evans thinks her manuscript - The Sad Fortunes of the Revered Amos Barton, her first work of fiction - has been destroyed). Her drawings of the Analytical Engine - which keeps expanding - are marvelous, especially when Evans wanders into it and Padua takes us on a tour, twisting and turning through it until we have to turn the book upside-down to follow what's going on. Padua's line is loose enough that the "action" scenes - there aren't many of them, but the characters are in motion a lot - are wonderful, with a lot of beautiful brush strokes that create a nice sense of movement and keep her figures from being too stiff. Even the relatively unnoticed inking - Babbage's tremendous hair, for instance - is amazing.

She uses nice grayscales throughout the book, too, adding nice texture to the drawings and making everything look more organic, especially when she uses it to contrast two different worlds late in the book. I don't get all the math in the book (to be fair, I'm kind of dumb!), but Padua does a good job drawing a lot of the conceptual stuff, and her depiction of the Analytical Engine in Appendix II is excellent.

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage is the kind of comic I wish would be more prominent, mainly because most people still think of comics as "superhero stories," despite so much recent evidence to the contrary. It's great that "real" publishing houses are putting out comics and more people are figuring out that they can be for everyone, but it would still be nice if some enterprising teacher, for instance, brought this into a math class and made students read it. It's not only very entertaining so it might be easier for students to deal with, but it's also full of fascinating knowledge about not only math and computers, but Victorian England in general. It's an excellent comic, the kind of book that gets better the more you think about it, and it's just another example of how amazing comics are. But you already knew that, didn't you?!?!?

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆