"Grab hold of me 'cause I'm your favorite fella; all they got inside is vacancy"

When I was at the Rose City Comic Convention in Portland a few weeks ago, Jonathan Case was nice enough to give me a copy of his new graphic novel, The New Deal. I say that he was nice enough because I had already pre-ordered it, and it was showing up at my comics store the following week, so I didn't want to buy a copy from Case himself, even though in a perfect world I'd buy all my comics directly from the creators so they get all my money.

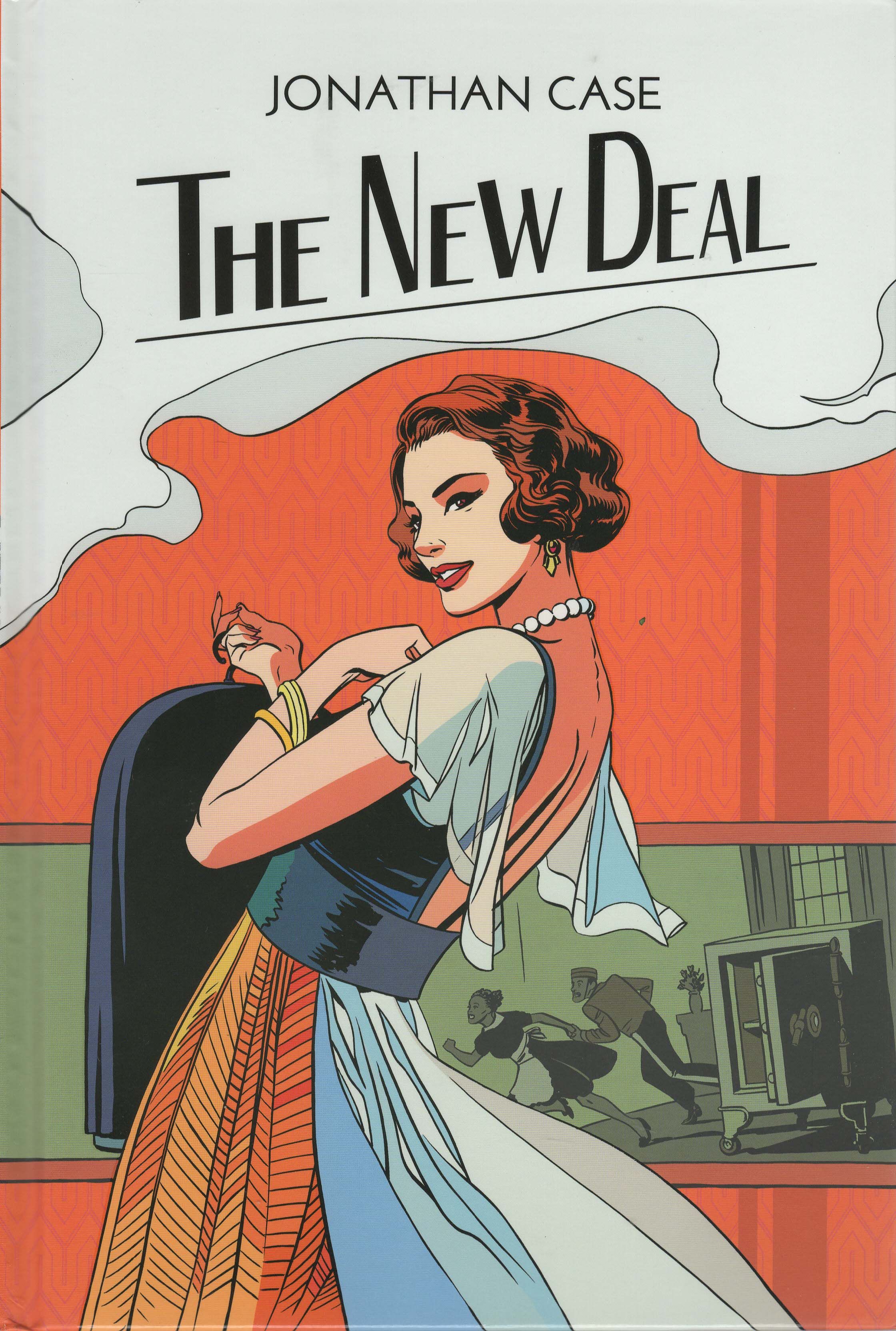

But he gave me a copy anyway and signed it (which is always nice), and I appreciate it. Now I've read it, so I get to write about it! The New Deal is published by Dark Horse and edited by Spencer Cushing and Sierra Hahn, and it costs $16.99.

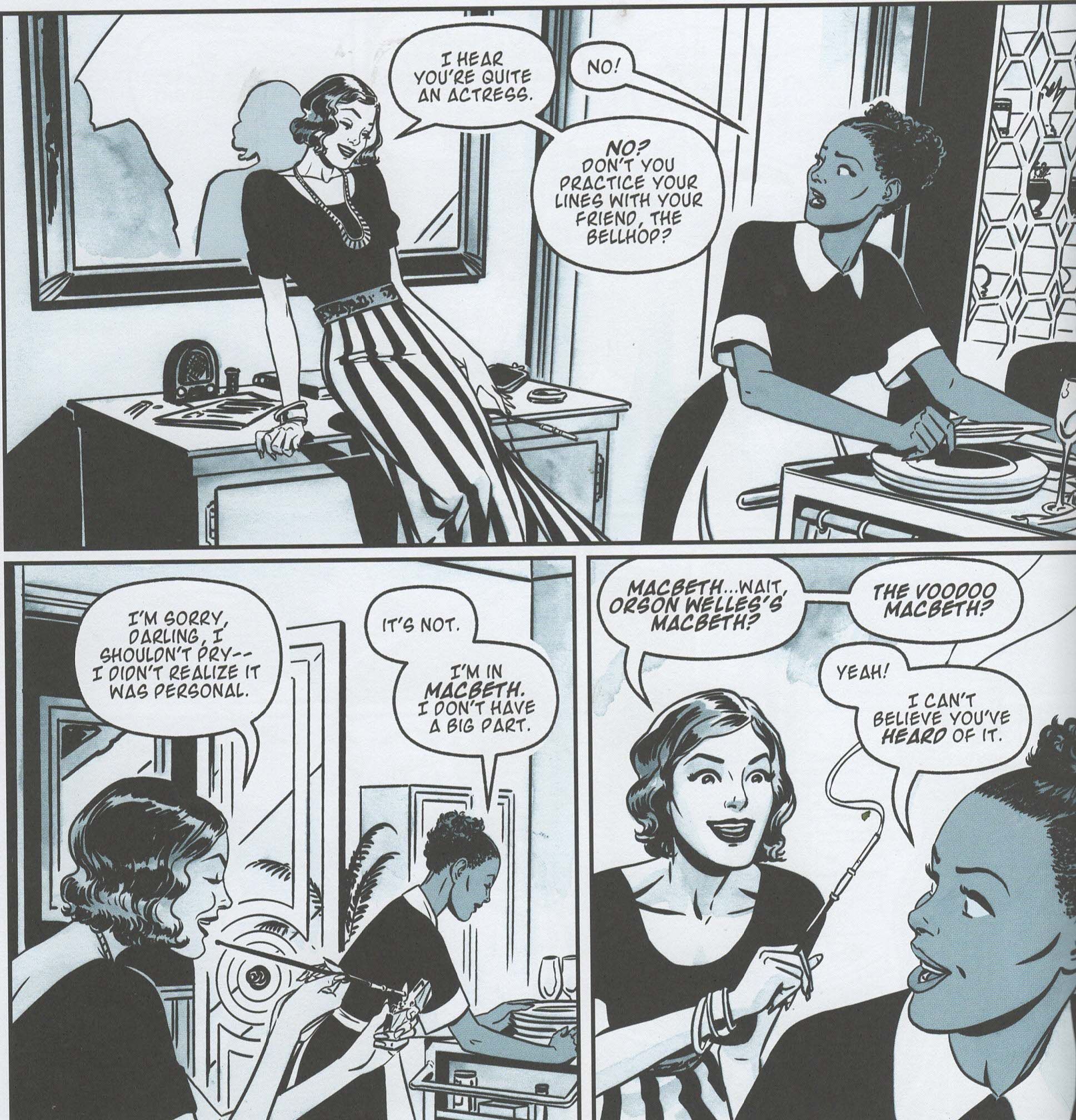

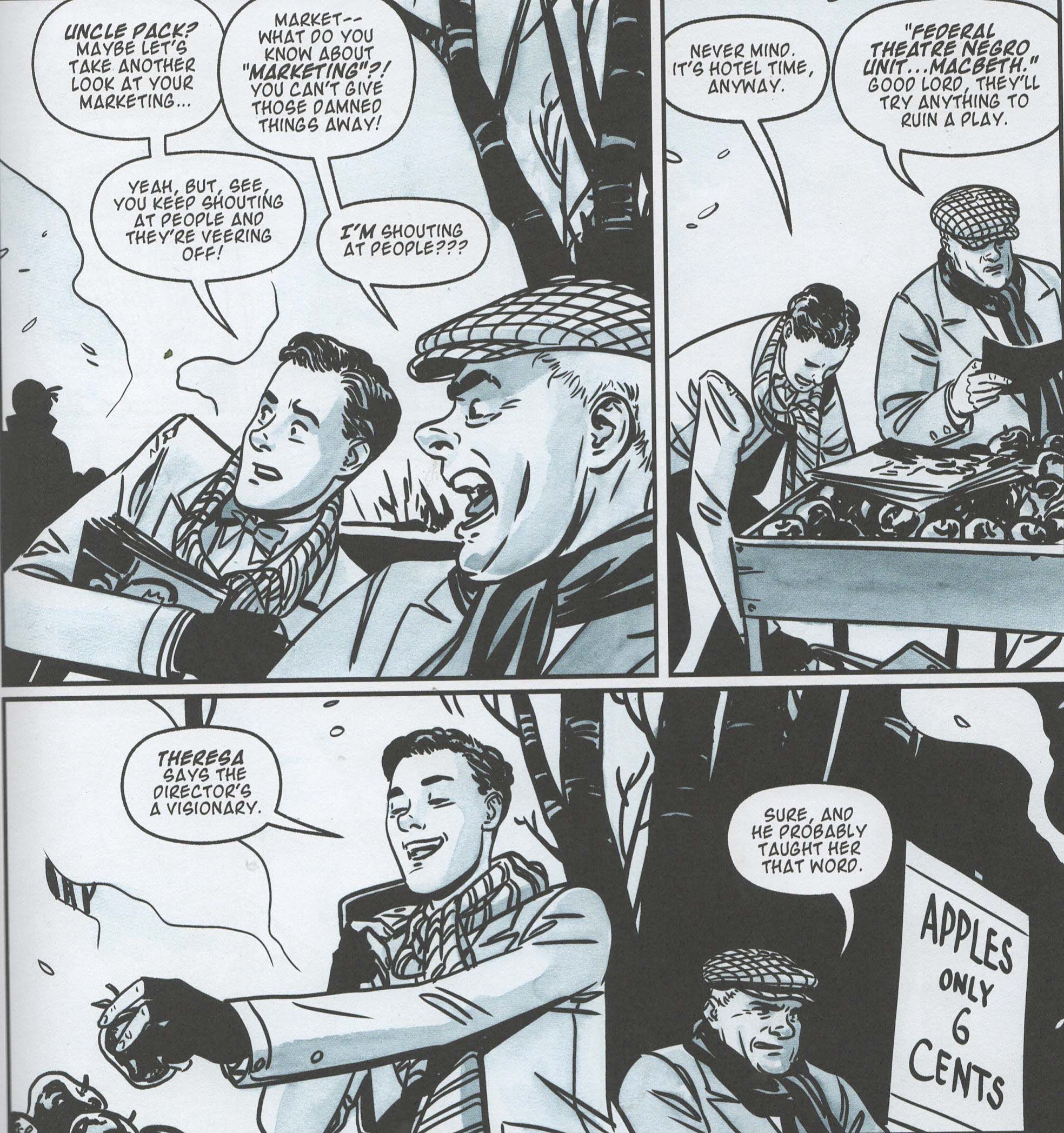

I've been a fan of Case's work for a few years now - Dear Creature is quite a nice comic, and in a artistic talent pool as deep as the one that works on Batman '66, his issues are the best - so I was looking forward to this book. It's a story set in 1936 New York, and it's interesting in that it couldn't be set in many other time periods - too many stories are set in different time periods just so the artists or writers or stars (depending on the medium) can draw/write/wear different clothing, but The New Deal really has to be set during the Depression, for any number of reasons. First of all, this is a time period when women were automatically discounted, and while I'm sure many people can give examples of that happening even today (I know, shocking!), it's not as automatic as it once was. It's also a time period when black people could have gainful employment at someplace like the Waldorf-Astoria, but that didn't mean that white people trusted them. But it's also a time period when black culture was beginning to interest white people, so Orson Welles's voodoo take on Macbeth is part of the story.

The social strata of whites is also part of the story - it's not stated but it is implied that Frank O'Malley, the male lead in the book, is Catholic, and Catholics during the 1930s were not trusted by the upper class, either, while it's also implied that the hotel manager is Jewish, so he's "low class" when looked upon by the guests, but he's higher up than the Catholics and blacks. Case also touches on the idea of inter-racial romance. The 1930s were also a time during which a good deal of the globe was still mysterious, so a treasure hunter like Jack Helmer could be a media sensation and get away with the theft of cultural artifacts without anyone raising many objections. Case takes all these elements and puts them in an interesting story, one that is indicative of its time but also speaks to larger themes in American cultural history.

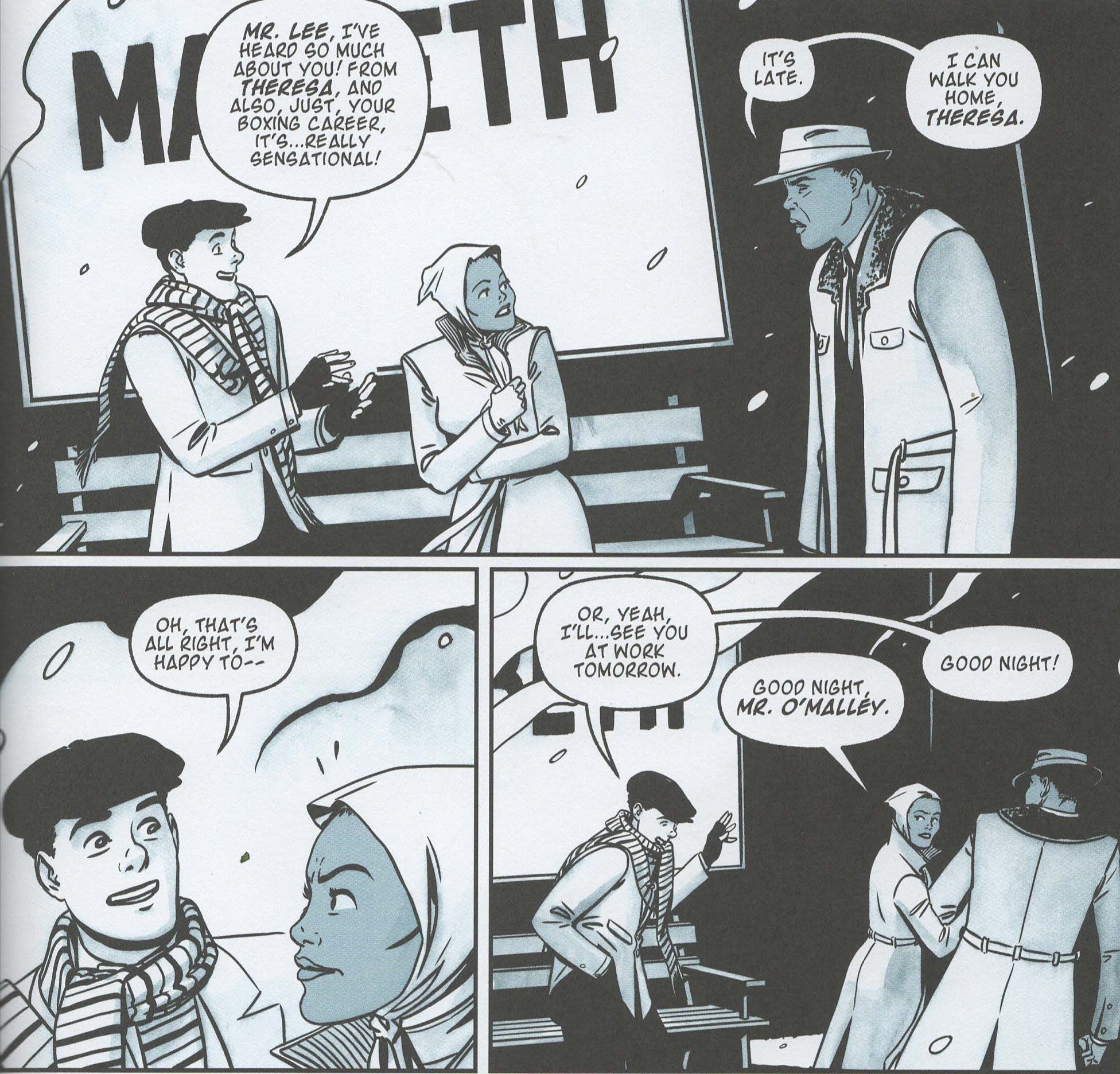

The plot, oddly enough, is slightly madcap, as Case manages to touch on all these topics without getting too heavy. Frank O'Malley is a bellhop at the Waldorf-Astoria who has a gambling problem - he owes $400 to Jack Helmer, a Howard Hughes-type adventurer who enjoys a good game of poker. Frank maintains a flirtatious relationship with Theresa Harris, a black maid who acts on the side (she's one of the witches in Welles's Macbeth, and Frank helps her run lines).

The comic reads a bit like a 1930s screwball comedy at times, with Frank and Theresa bickering like a couple deeply in love but not willing to admit it, and Case's dialogue is very crisp, revealing quite a bit about both characters. Theresa is more serious than Frank, but neither character is too serious nor too flippant. Frank doesn't know how he's going to raise the money, and Helmer has the power to get him fired, which in 1936 was a dire predicament. Meanwhile, a woman named Nina Booth checks into the hotel, and she is quite dazzling. Frank (and every other man) is smitten with her, and she treats Theresa like a person, so Theresa is a bit smitten, as well. Case puts all these characters in place and then cranks up the plot: something is stolen, and suspicion falls on the black maid, naturally. Theresa manages to keep her job (thanks to Nina's intervention), but Case cleverly shows that everyone is in need of money, so Theresa might be the culprit, but so might Frank. Or even the upper-class guests like Nina or Jack Helmer. The identity of the thief isn't really the point, as things get sorted fairly quickly, but what is the point is that during this time period, desperation might drive anyone to steal. And in a charged atmosphere like we get in the book, the ugliness of humanity's nature rises to the surface as well. Everyone is quick to suspect Theresa, and when Frank tries to defend her, he almost loses his job, not because of his actions, but because the veneer of respectability is everything to the manager of the hotel.

It's the idea of "high society" that allows some people to act with impunity and causes others to attract attention from the law - there's no proof that Theresa did anything wrong, but because a respectable white woman claims she did, she's a suspect. When Theresa is no longer under direct suspicion, Case once again plays with this idea to set up a bigger scheme involving Theresa and Frank. This isn't a new or unique idea, but it's a fertile one, and Case is able to use it quite deftly to give us a nicely-plotted crime comic. Those are always fun.

As I noted, he introduces plenty of more serious subjects, but handles them well. Theresa and Frank obviously dig each other, but that step is too much even for them - they both seem to fear the consequences from others, from Frank's racist uncle to Theresa's disapproving black friends. Case links the theft of the trinkets at the hotel to Helmer's thefts of cultural artifacts, and why is one worse than the other? Theresa quits Macbeth because she says she doesn't want to take orders anymore, and Case cleverly subverts this declaration of freedom and Theresa's yearning for independence (Welles's somewhat subtle racism contributes to her decision) by her explaining a different reason for quitting (which I don't want to give away, so I won't). Is Nina truly enlightened and doesn't care about race, or does she treat Theresa well because she's a woman and she knows that people overlook her (she seems to imply that) or because of something more sinister? And could it be all three reasons?

Case does this kind of thing very well - he introduces complicated ideas and doesn't answer them, letting the reader speculate about the motives of the characters. This allows him to keep the tone light while still bringing up themes that delve into the problematic society of the United States, both in the 1930s and today (where we're confronted by many of the same issues). The book is still genteel, but there's darkness at its core.

Case's art, naturally, is wonderful. He's become more "realistic" over the years, but he hasn't lost that cartoony fluidity that makes his art so stylish. He grounds the book in the reality of life in 1936 New York, but doesn't dwell on the seediness of the lower classes - the idea, as with the writing, is to turn this almost into a comedy of manners, so when the crime aspect comes up it's jarring, but Case cleverly links the idea of respectability in the writing with the Art Deco romance in the art. The few times he ventures outside the Waldorf-Astoria, the realer world intrudes, and while those few scenes don't overwhelm the fairy-tale world that people like Mrs. Pendleton, Nina, and Jack Helmer inhabit, they do show that it is a fairy-tale world, and they're hiding from the tragedy outside their bubble. Case's characters are terrific - Frank is a bit more cartoony than most of the characters, so his naïveté when it comes to, say, poker (both he and Theresa know she's better at lying than he is) comes through on his face, while Theresa is a bit more hardened by the world, showing us that as bad as Frank's situation is, it's not as bad as Theresa's. Nina is utterly dazzling, as Case not only draws her stunningly, but puts her in amazing clothing throughout.

He does some wonderful things with the servility of the hotel staff juxtaposed against the brashness of the upper crust, too - just the way he shows their body language is enough to show us who's on the top of the pecking order and where everyone fits. I really don't want to spoil anything, but when the identity of the thief is revealed, Case is terrific at showing the way the thief changes from before the revelation, and he does it all just by the way the thief moves and looks at other characters. And in the climax of the comic, Case not only plays on what society expects, but draws a character in just such a way that we can believe the plan said character is enacting. It's really well done. As with any good visual medium, the characters have to "speak" non-verbally at times, and Case does wonderfully with that to make points about the society in which these characters live that would be too blatant if he wrote them down. It's all part of his subtle look at the culture of the times (and our own) and how he doesn't provide answers, just makes us think about it. Like the writing, the art keeps the tone light but hints at the darkness underneath.

"The New Deal" refers to Roosevelt's economic plan, of course (which Helmer disapproves of), but it's a nice play on words, too. Many characters in the book are dealers, and whether they can play the game well or not indicates whether they will change their lives or not. Case does a terrific job balancing the lightness of a high-society crime spree against the realities of life during the Depression, and he makes the book far more complex than it appears on the surface. The New Deal is a very good comic, and if you enjoyed Case's work on Batman '66, you should definitely check it out.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆