"You don't have to wear that dress tonight, walk the streets for money"

The second Caliber book I bought recently is Storyville: The Prostitute Murders, which is written by Caliber Grand Poobah Gary Reed, drawn by Wayne Reid (with a short sequence by Mark Bloodworth), and lettered by Nate Pride. It will set you back $19.99 if you choose to pick it up.

In case you've never heard of Storyville, it was the red light district in New Orleans between 1897 and 1917.

This comic takes place in 1910 and it's set in the district as well as St. James Infirmary, which is an insane asylum near the district. While the book is a murder mystery, Reed is as interested in the places and the people who live there as he is in the actual mystery. He introduces us to the main characters - Brian Donahue is the detective assigned to the murders, and he is told to use Dr. Eric Trevor, the new psychiatrist at the infirmary, as a consultant. Donahue resists at first, but he finds in Trevor a valuable ally. Reed also introduces us to the famous madams of Storyville, as well as many other colorful characters. The interesting thing about the book is that the murders, while not exactly an afterthought, are a symptom of a much bigger issue in the city, and even the title of the comic is a misnomer, as the prostitutes are not really the target of the murderer. Perhaps "Prostitute Murders" had a better ring to it, but their deaths, even more than the deaths of the intended victims, are a symptom of the times rather than the point of the murderer.

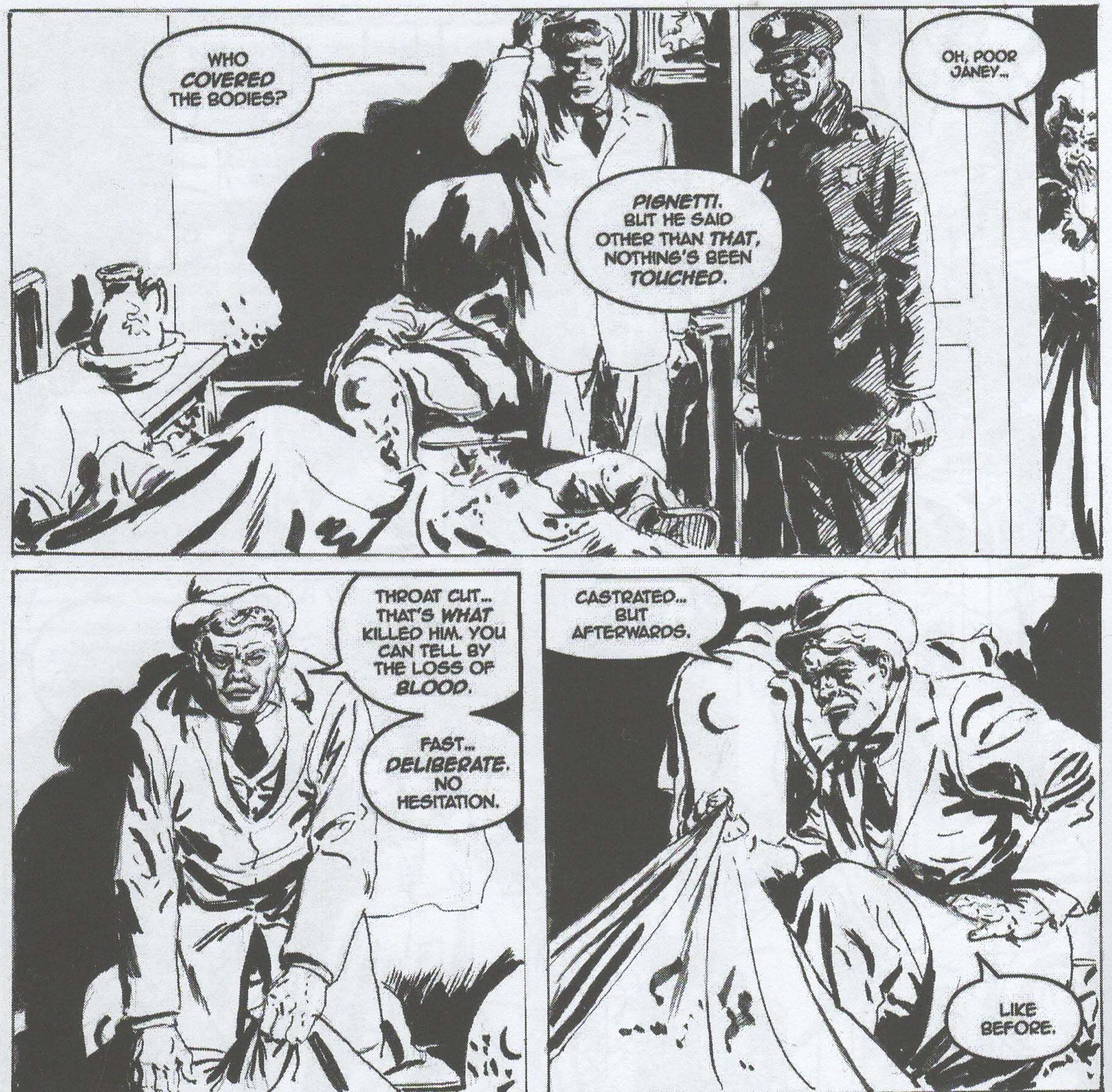

Reed spools out the case well - with a lot of murder mysteries, there's always the temptation by the writer to withhold information from the reader, and while I understand that, I've never liked it, and Reed resists here. We find out things fairly naturally, mostly as the characters do, and when the murderer is revealed, it's in an amusing and fairly naturalistic manner.

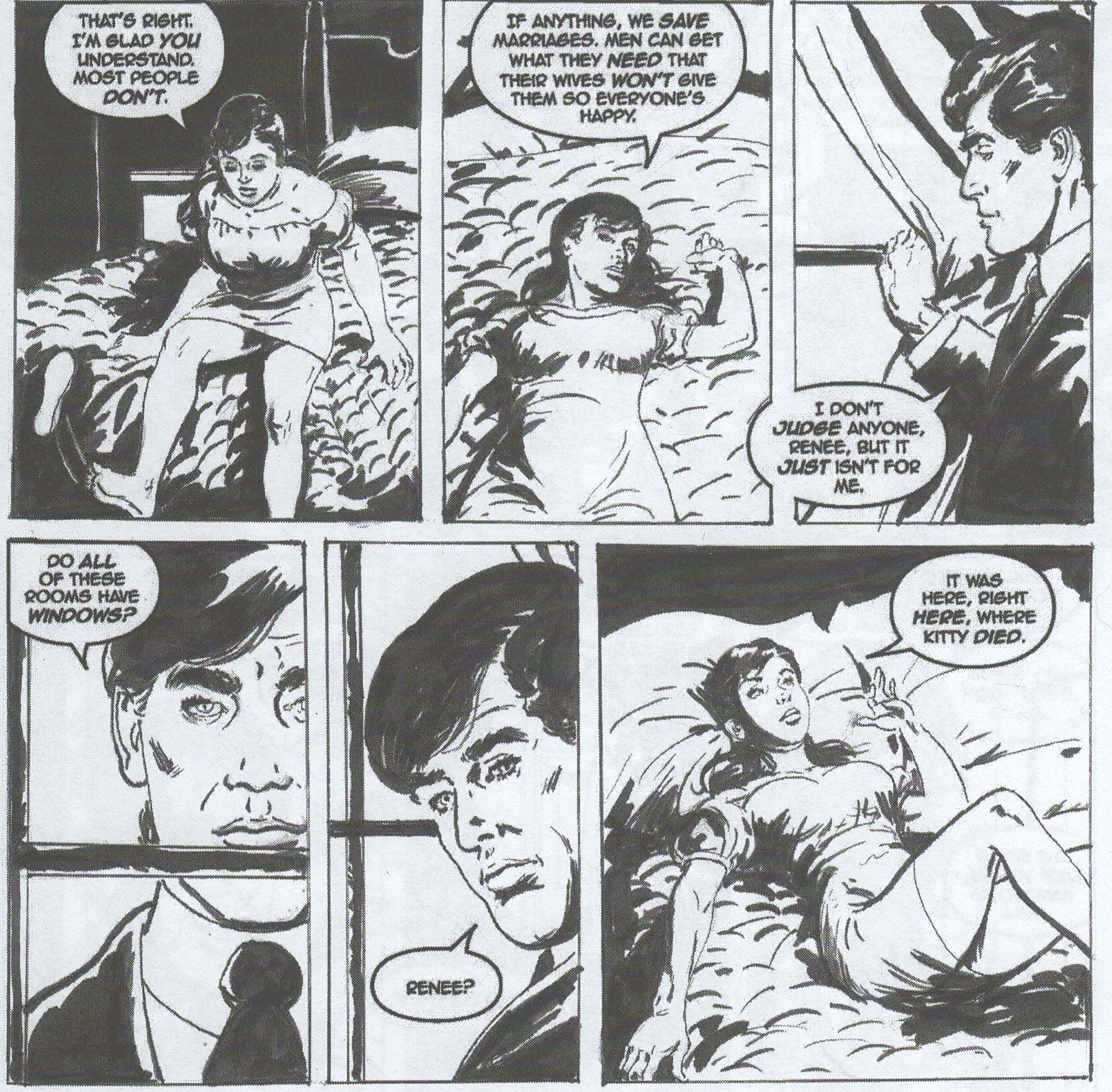

As I noted, Reed is more interested in the conditions in the city in 1910, so he spends a lot of time at the "infirmary" with Dr. Trevor trying to delve into the mind of a 15-year-old boy who inexplicably murdered two 9-year-old girls and then turned himself into the police. Trevor can't understand why the boy did it and why he doesn't seem to feel any guilt about it - he turned himself in, Trevor believes, because he knew society would say it was wrong, not because he felt that way. Reed takes us into the infirmary to show how insanity was treated in the early 20th century, and while Trevor still does some unusual things, he's far more progressive than those he replaces (he's the new administrator as the book begins). Donahue is similar - he's a cop from Chicago who is unused to the racism of New Orleans, so he gives a job to a black man even though the man is not allowed to be on the actual police force (until Donahue forces the mayor's hand at the end of the book, when he has some leverage). Donahue tries to investigate based on following evidence rather than just scapegoating, and he faces an uphill battle as well. Reed gives us interesting female characters too - the two main ones are a former prostitute who is moving into the administrative side of the business and Dr. Trevor's new secretary, who is trying to focus on work and shuts down the little romantic interest that Trevor shows in her even though she wants to indulge herself.

It's a reminder that romance at this time meant that the woman would immediately give up their job and become a wife, even if that job was prostitute - Renee, the ex-prostitute, doesn't let herself become romantically attached because even that would mean she'd have to become a housewife.

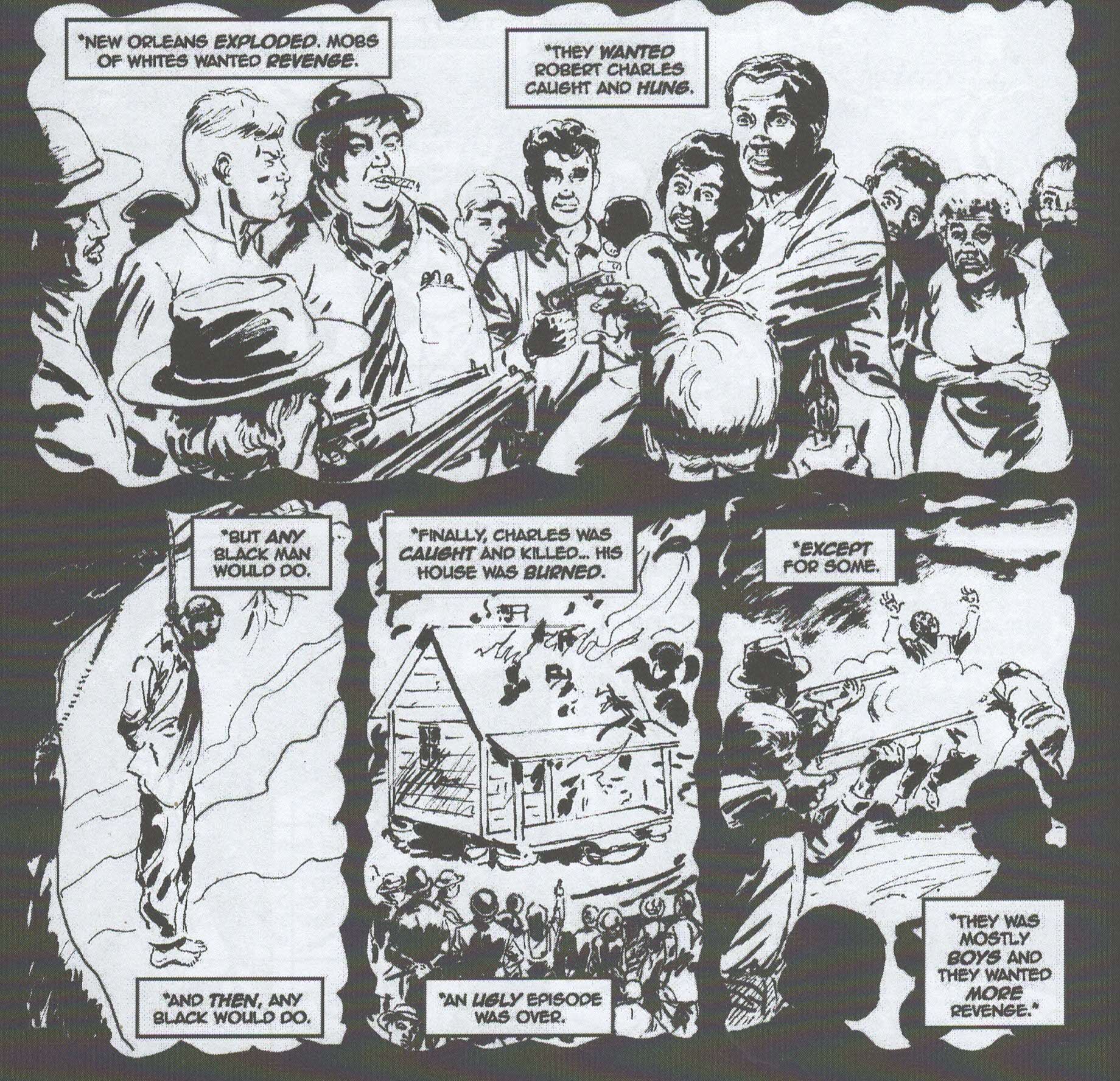

So we have a lot of social issues going on, and the murders are a consequence of what happens when you pack so many different kinds of people into a small space. Reed gets into the hypocrisy of the white elite a little, but it's more than that - the rich white men frequent the brothels, of course, but they don't interfere with the businesses, they just want things to remain discreet. When it seems that they're trying to cover up the murders, it's more because it would be bad for business rather than because they're protecting one of their own. As Donahue digs into the case, he learns of the existence of a cabal of businessmen who seem to be connected to the murders, but Reed resists the immediate assumption on our part that they're evil. They're connected to the case, but not in the way you might think. He shows us how the rich whites in the city might want segregation, but they're also concerned about the health and welfare of the black community. Reed doesn't shy away from racial tensions - the black "cop," Mordecai, tells Trevor about ugly race riots in the city, and even that ties into the murders, if only indirectly. But Reed doesn't let the characters become stereotypes - even the minor ones and the seemingly evil ones have reasons for their actions, and they're completely understandable. The book is more complex than you might expect, which is nice. Reed draws us in with the sensational - the murders of prostitutes in a city-ordained red light district - but he uses that to get into the society of the time, turning it into an interesting microcosm of American life 100 years ago.

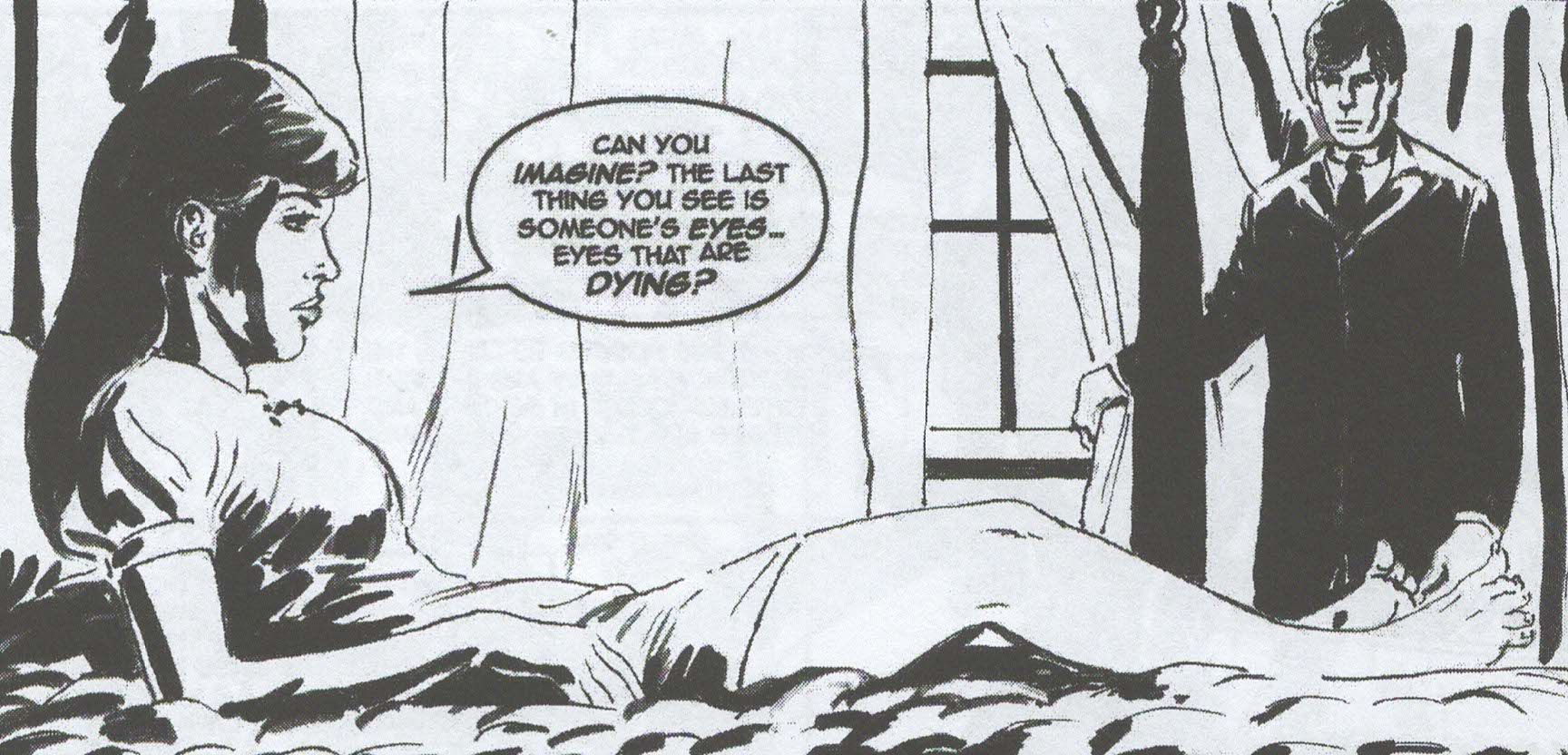

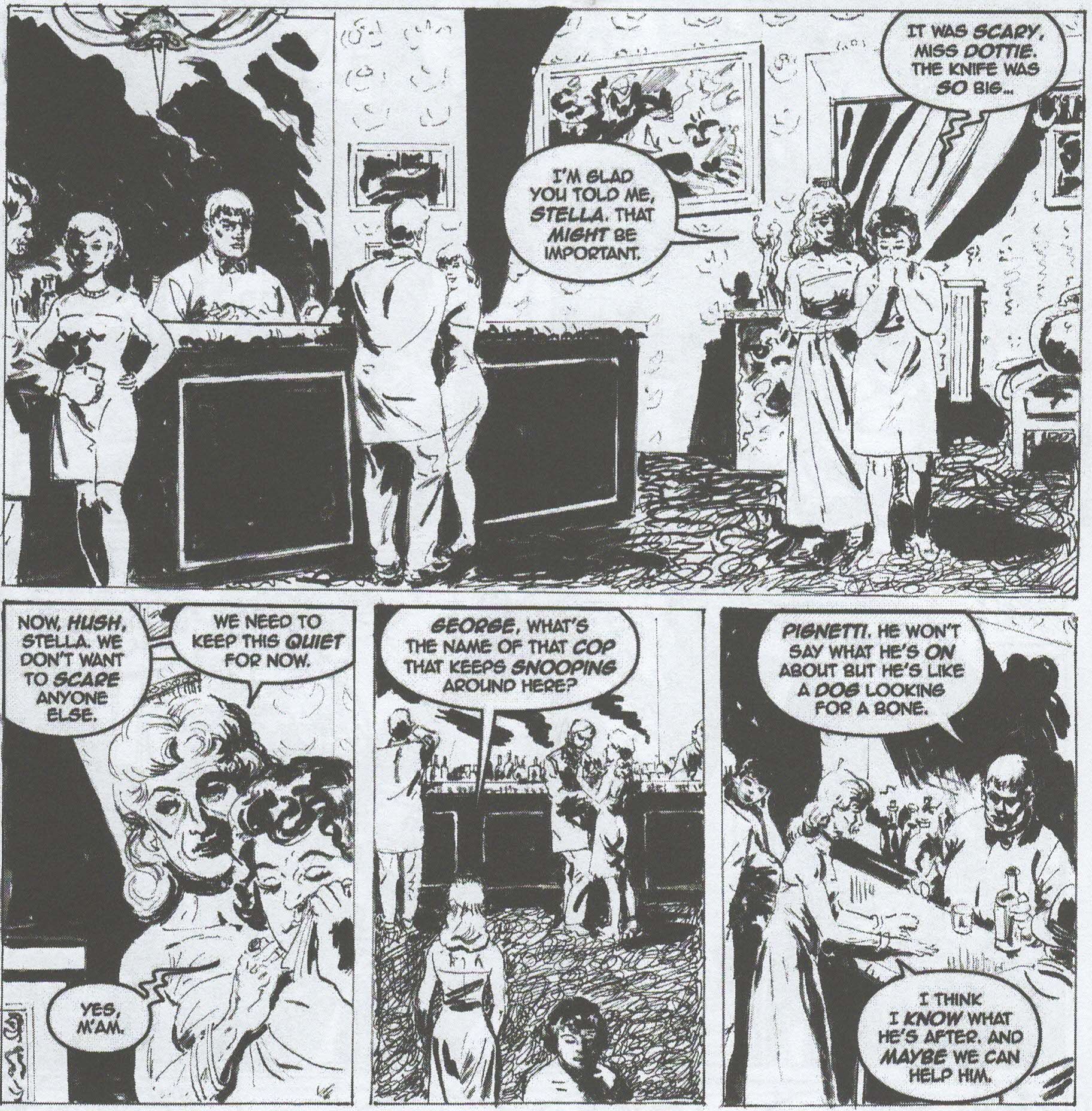

Reid's art does the job, although Reed doesn't give him too many opportunities to shine. Reid uses a smudgy brush for a lot of the book, which allows him to add texture to the sky above New Orleans - it looks polluted, which I imagine it was - and to the grimy streets.

He uses a slightly thinner line inside the brothels, but even there his brush makes the interiors look a bit more seedy than the madams would probably admit to them being - there's a veneer of class but the roughness of the settings is still obvious. He uses blacks really well, both too reflect the dark tone of the book but also to show that in a world where electric light was still a novelty, there were more shadows. Reid doesn't get to draw too much action, but he does fine with it when he does. His characters are well drawn, distinct enough that it's not difficult to tell them apart, which in historical comics is occasionally hard, as the men all tend to have mustaches and wear suits all the time. The interesting thing about his women is that they look a bit too modern. Throughout the book, Reed drops in photographs of actual prostitutes from Storyville, from a book published in 1912. Reid's women are perfectly fine, but he doesn't quite get the hair styles and even the body types of the women in the photographs. Drawing women from different eras has to be, I imagine, one of the most difficult things in a historical setting (far harder than drawing men), because of the different ideas of beauty that society has had throughout the centuries, and Reid doesn't quite get it. Still, that's just something that struck me when I looked at the actual photographs, because otherwise, Reid's women are done well - unlike a lot of artists, he does manage to differentiate the many women in the story from each other. That's not a bad thing.

Storyville is an interesting comic because it's far less sensationalistic than you might expect from the title. Reed is concerned with the murders of the women, but at the same time, he seems as or more interested in the idea of Storyville, the people living in it, and the way New Orleans society reflected American values of the time. This is a good time to set a murder mystery, because so much of society at that time is familiar to us but it's also still foreign enough that things seem strange. Lots of things were happening that America is still grappling with, and Reed manages to bring them up within the context of the story, so they don't feel shoved in just to fit an agenda. It's not a bad trick. Reed has always been a clever writer, and it's nice to see him be a bit less melodramatic and more naturalistic. So if you're at all interested in American history, especially Gilded Age history, this is a nice book to check out.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆ ☆