"If you voted for the man you're wasting time, he's got his fingers dipped in everyone's pie"

There are people in this world, if you can believe it, who find history boring. I KNOW, IT'S CRAZY!!!! They believe that because history is simply a recitation of "what happened," that it's boring and has no relevance to today's world. I would argue that if certain politicians knew history, they would have known that invading Afghanistan was a fool's errand and the trauma of the past decade would have been extremely lessened (of course, they could have just listened to Wallace Shawn, because even William Goldman knows history!!!), but that's not important right now.

The point is that history is far more than just a recitation of "what happened," as we're always learning new things about what happened, so we're constantly revising our ideas about the past. Part of the problem is historical writing, which is often terribly dry. Historians don't tend to be good writers, and that hurts them when they're trying to reach a wider audience. So those who are predisposed to dislike history don't get any incentive to learn more about it when they read dry accounts of "what happened."

It's at this point where I'm supposed to tell you that Nina Bunjevac, the writer/artist of Fatherland: A Family Memoir (which costs $22.95 and comes to us from Liveright Publishing), makes history come alive through this comic about her father and his experiences in Serbia during the 1940s and 1950s and in Canada during the 1960s and 1970s. I'd like to tell you that, but I can't. Bunjevac might not be a historian, but it seems like she thinks she needs to write like one, and the book suffers greatly for it.

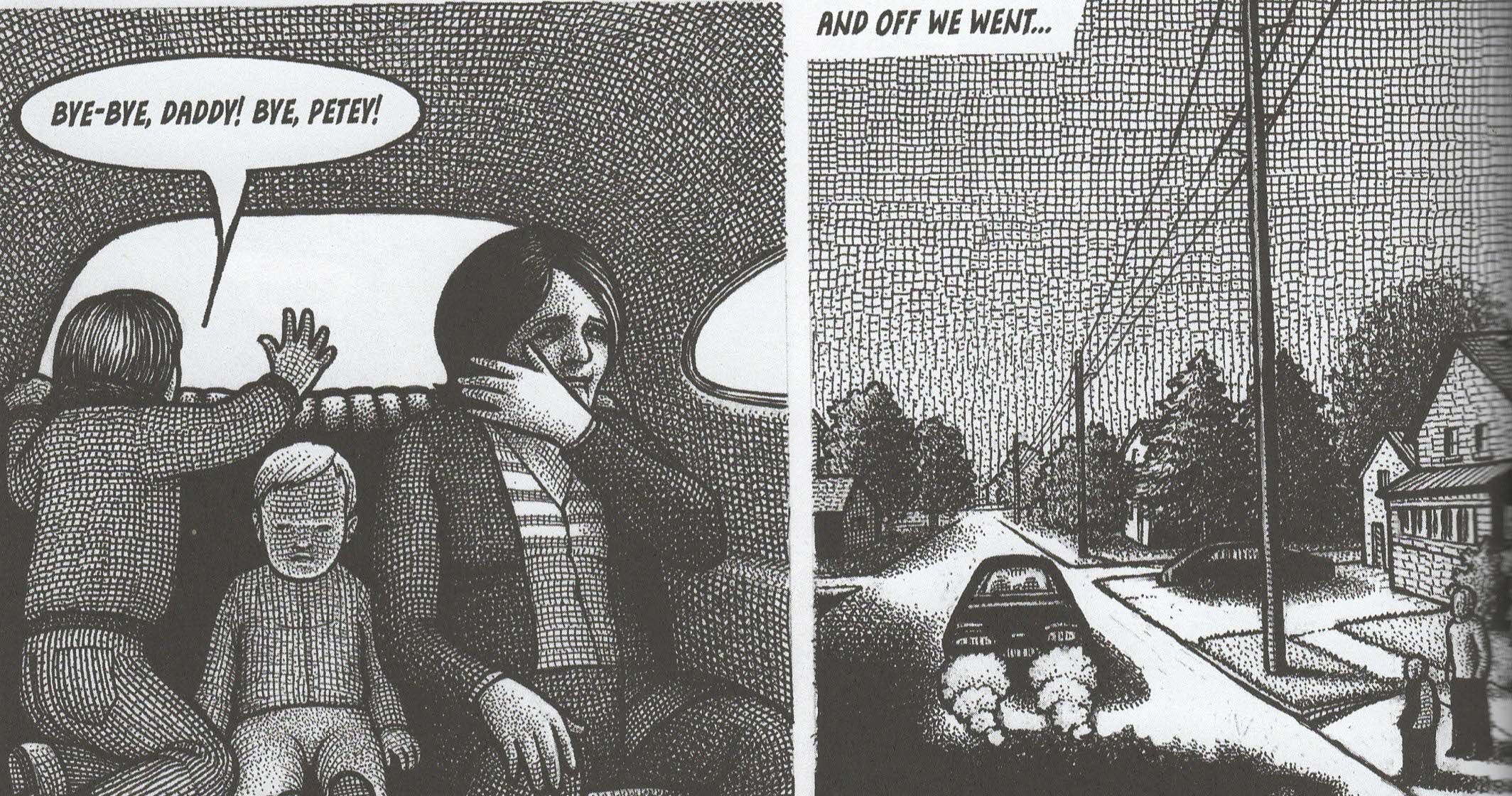

There's a fascinating story here, as Bunjevac tells us about her mother leaving her husband, Nina's father, and fleeing Canada for Yugoslavia in 1975, taking her two daughters but leaving her son behind, and not returning until after Peter Bunjevac died making a bomb a few years later. Peter is a Serbian terrorist, and Nina's mother can't deal with that, so she leaves. This is the stuff of great fiction, even great non-fiction, but Bunjevac isn't up to the task. It's very frustrating.

Part of the problem with the book is that Nina didn't know her father very well at all. She was born in 1973, so she was only 2 when the family left and only 4 when her father died. So any emotional connection to her father which might complicate her relationship with him and his terrorist activities is lacking. Yes, it probably was a bit traumatic to find out her father set bombs across Canada and the United States and was killed making another one, but it couldn't have been that emotionally crippling, and Bunjevac herself doesn't seem that affected by it.

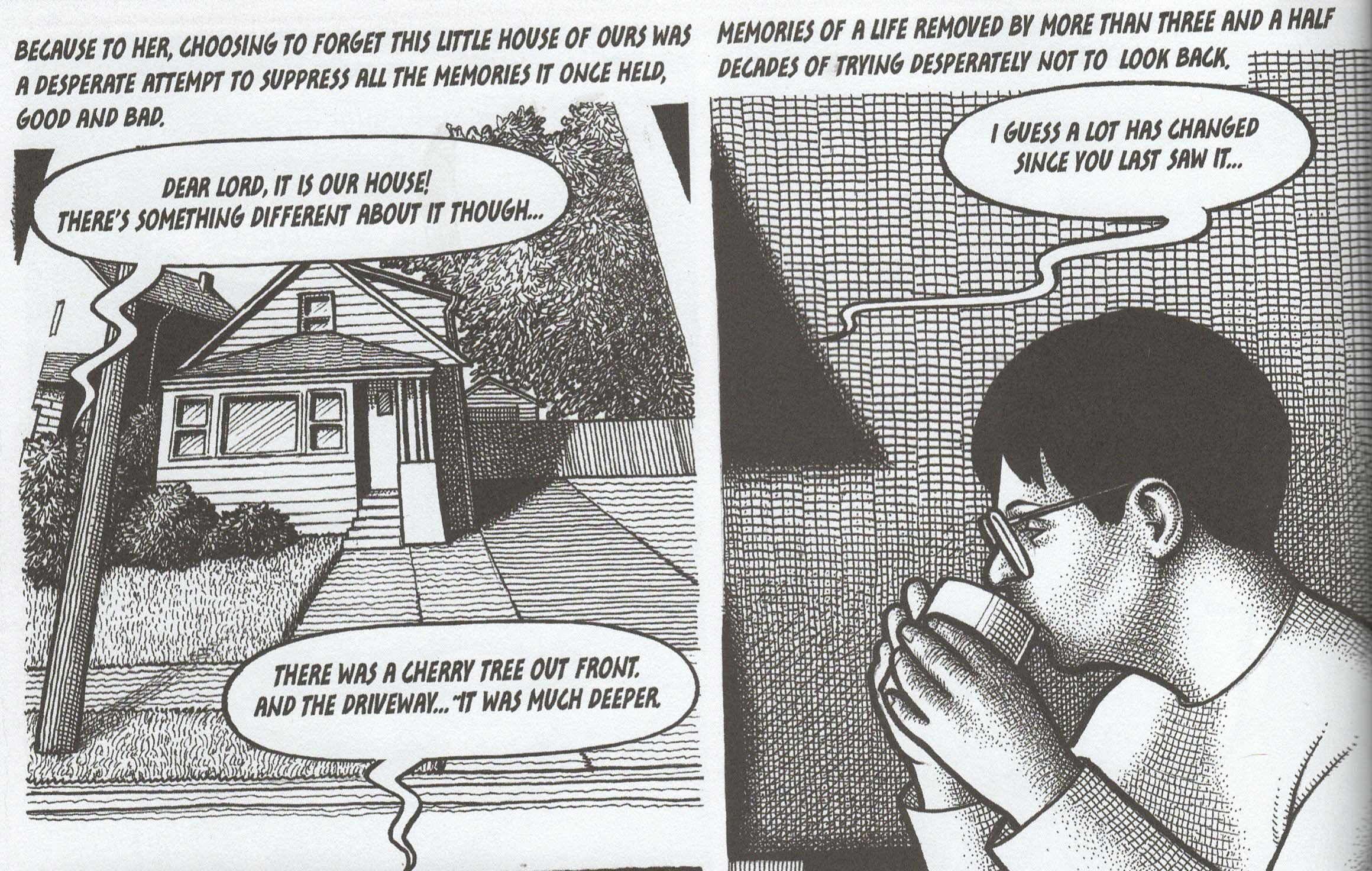

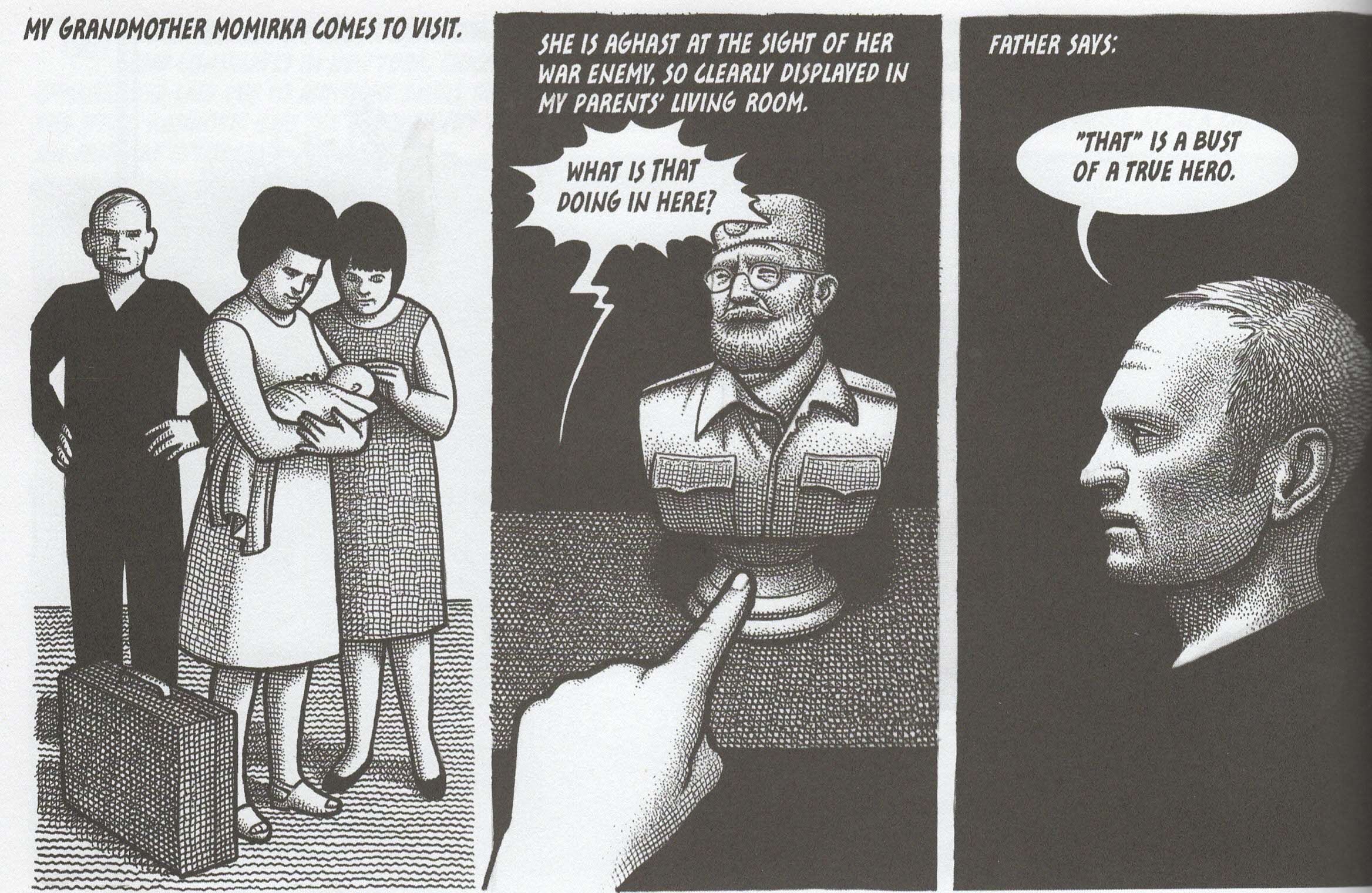

Her father was dead by the time she was old enough to understand what kind of a man he was, and there's nothing in the book that shows us her own inner thoughts about her father and his legacy. The adult Nina isn't much of a presence in the book, in fact. She talks to her mom after finding a photograph of their old house, and her mom reminisces about her husband and her family in Yugoslavia. So that is second-hand knowledge, and naturally filtered through everyone's own biases. But even with that potential, there's very little drama in the book. Nina's mother's relationship with Peter is sketched out in very few pages, and although we can guess it takes a great deal of strength to leave him (and her young son) behind in Canada to return to Yugoslavia, of all places, very little of that comes through. Nina's grandmother is the most interesting character in the book, but because she just rants unopposed, we don't get any challenges to her version of history. She hates Peter because he's a royalist who hates Communists, and as Yugoslavian Communists fought against the Nazis, they're revered in the country. However, even Nina's grandmother admits that the post-war Communist government isn't the greatest, but that part of the book isn't explored at all. Bunjevac isn't that interested in exploring the divisions in Yugoslavian society, circa 1977.

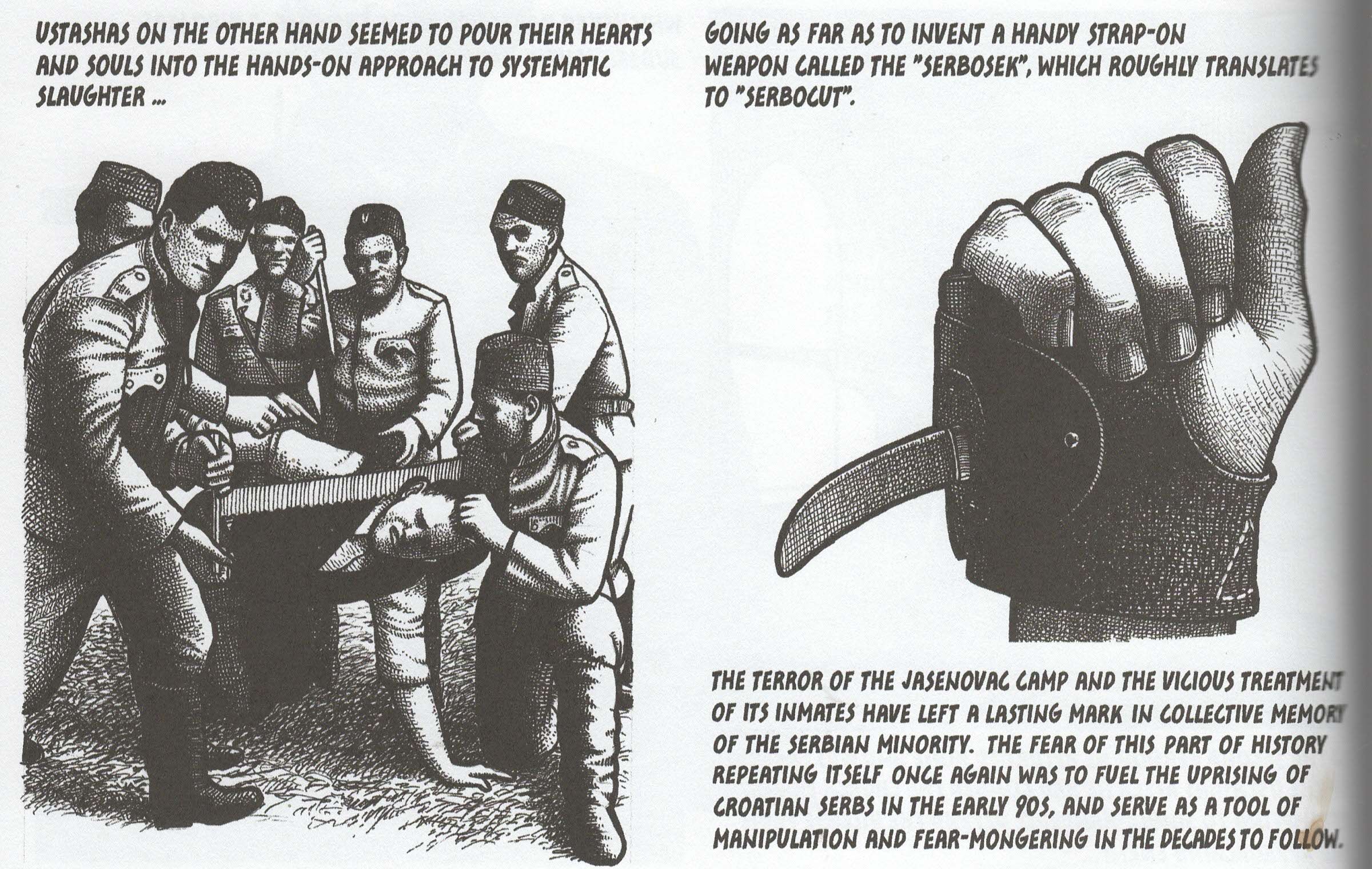

What is she interested in? Well, in the second half of the book, she delves in Balkan history, and while Balkan history is complicated, violent, and tragic, she manages to make it fairly dull. For a good deal of the book it's simply a dreaded recitation of facts, with the grand events of Balkan history interspersed with Peter's personal history, neither of which Bunjevac manages to instill with much drama.

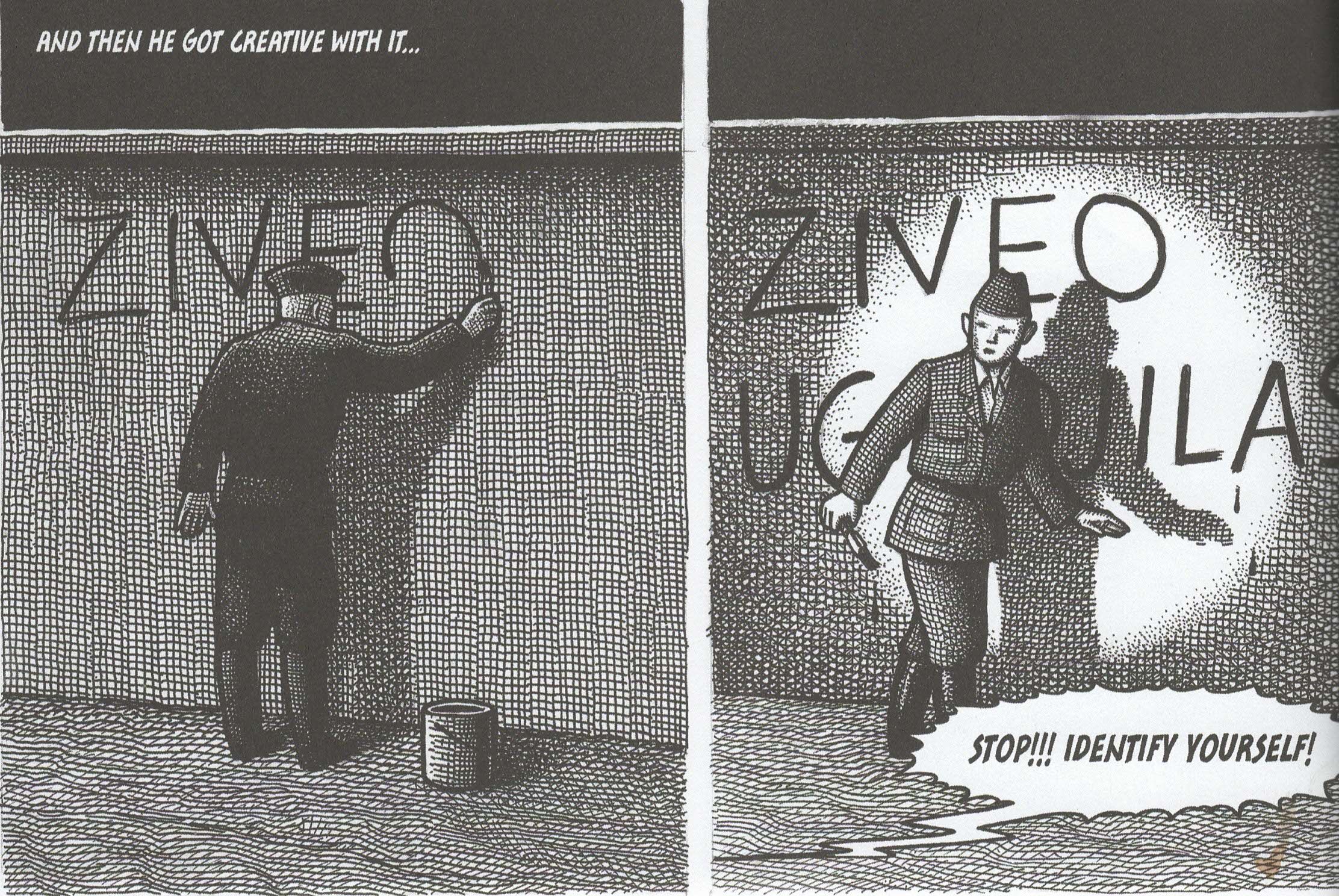

Peter was beaten by his father, who eventually ended up in a concentration camp in 1945, from which he never returned. Peter's mother died not long afterward, and he became a thorn in his own grandparents' side. He spent time in the military, but was imprisoned when he supported one of the Communist leaders who criticized Josip Broz Tito, the long-time ruler of Yugoslavia. After prison, he fled to Canada and drifted into the orbit of Serb nationalists. There's no sense of Peter or his personality, so there's no sense of action on his part - events just conspire to move him from place to place, and Nina herself writes that when he read about a meeting of Serb nationalists he felt "compelled to attend." Why? Prior to his moving to Canada, there was no indication that he was a fervent Serb nationalist. His hero is Draža Mihailović, a World War II general who remained loyal to the Yugoslavian dynasty, which meant they occasionally collaborated with the Axis to fight against the Communists. We can infer some things about Peter - his father beating him and then fighting for the Communists, his friendship with a German officer during the occupation, his military career - that might point to a royalist, anti-Communist leaning, but Bunjevac makes these connections so vague that his extreme commitment to the cause seems a bit off-kilter with his previous life.

Sure, I can buy that he might hate Communists, but would that lead him to blowing up innocent people? It seems like a leap.

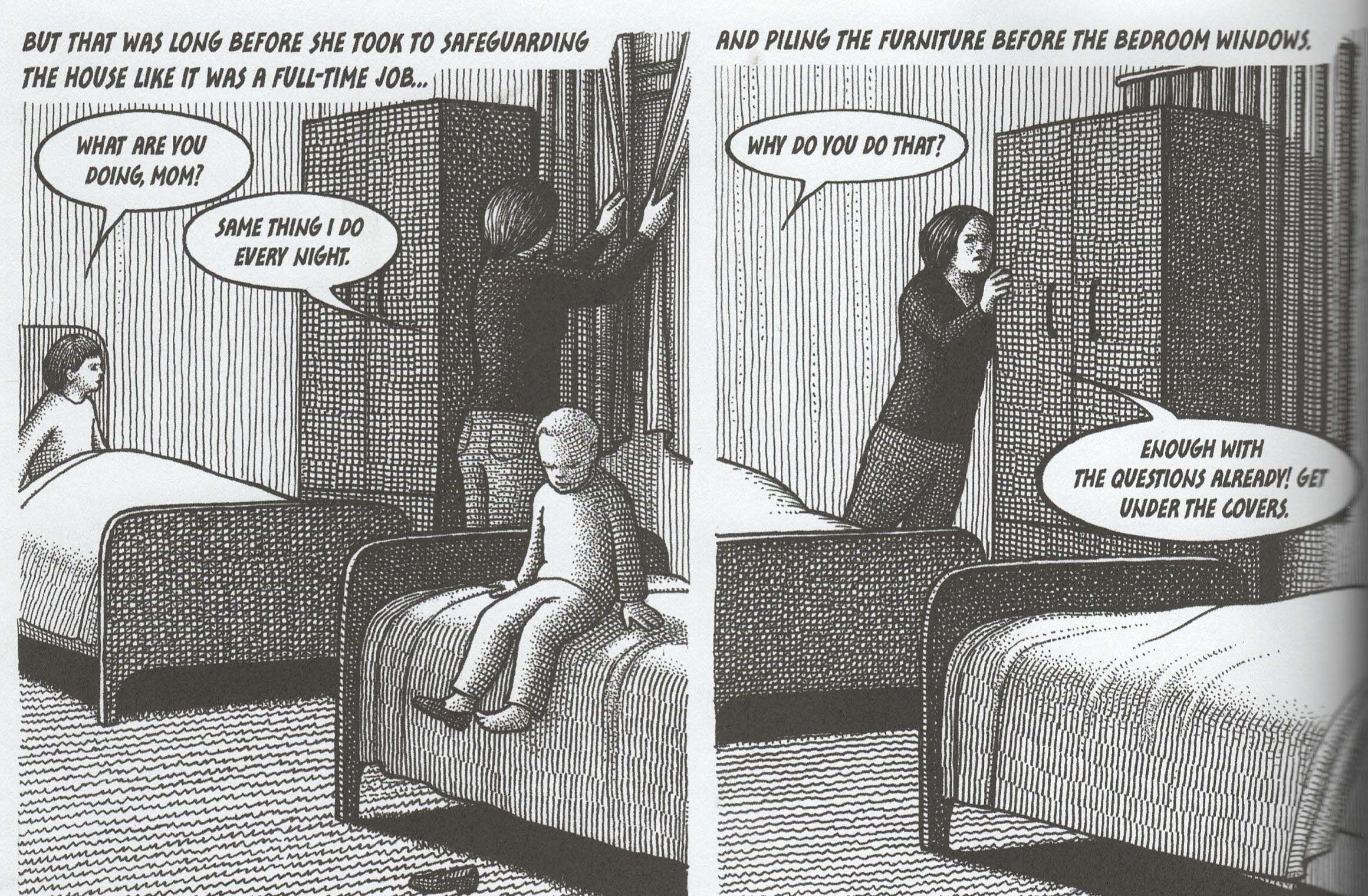

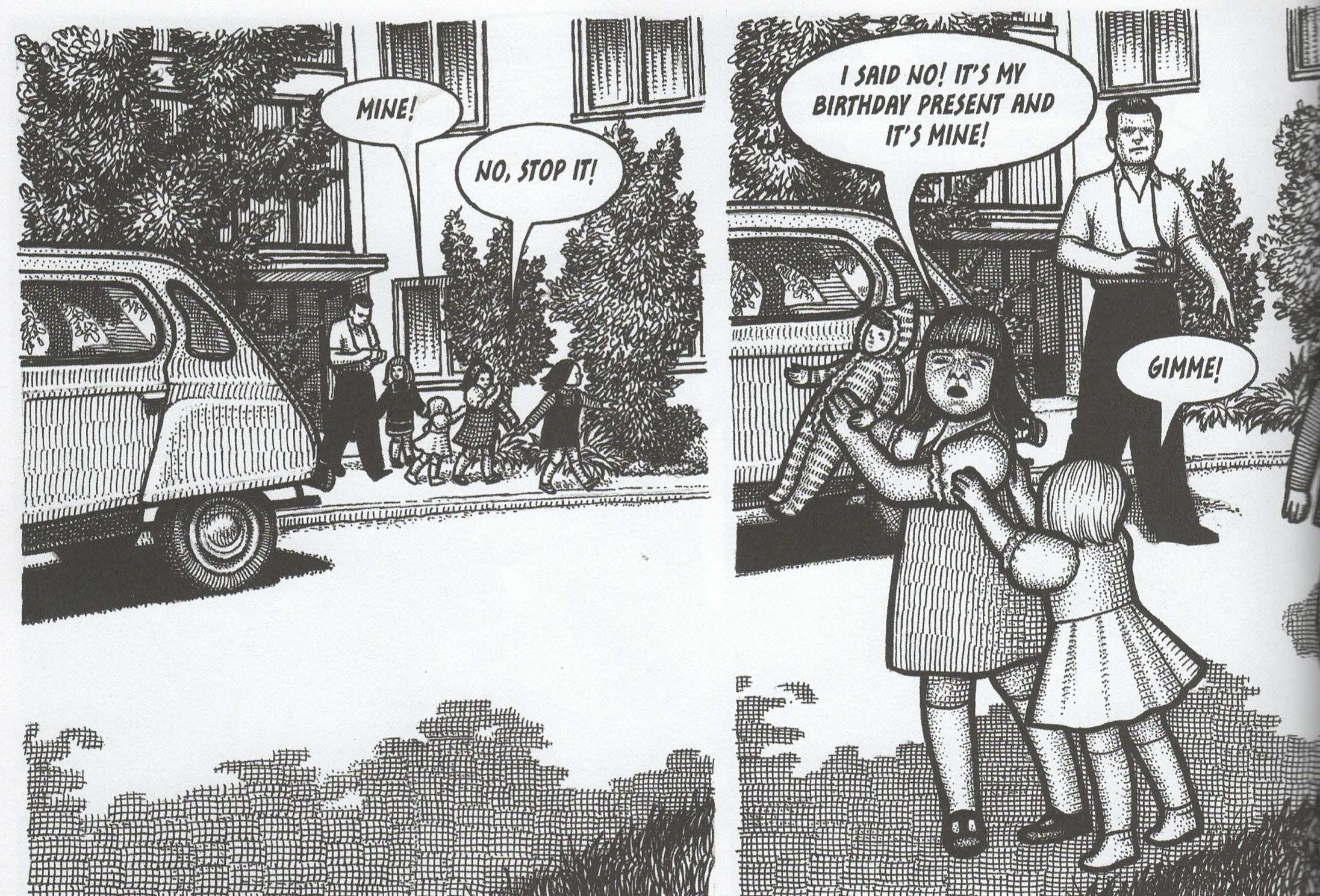

This detachment from people extends to others, too. The book ends oddly, with an emotional moment between two ancillary characters who Nina hasn't bothered to develop too much, and it doesn't feel earned at all. Nina's sister remains a cipher, as the only time she really comes alive is when the toddler Nina wants to play with the doll she just received for her birthday and she doesn't want to let Nina have it. The most emotionally affecting scenes are the ones between the adult Nina and her mother in 2012, when Nina probes about her father a bit. Bunjevac keeps the conversation simple, which allows her to load it with more allusions than the rest of the book, and the terrific way she draws her mother refusing to look directly at Nina speaks volumes. But those scenes are short, and they certainly don't make up for the stilted style in which she tells the rest of the story. A tale about the struggle between Communists and their enemies in Yugoslavia and a terrorist in the Canadian heartland shouldn't be this dry, but it is, sadly.

Bunjevac does a nice job with the artwork, however. It's not fancy, but her attention to detail is very nice, as is the way she uses an almost pointillist style and many short lines to add texture to everything. She gives everyone in the book a weathered, beaten look, which shows the tribulations they've gone through quite nicely.

She doesn't give us too many exterior shots of Yugoslavia in the 1970s, but even those details give us a good idea of the different society, and when she shows Peter's childhood, she gets more into the rural life in the Balkans during the 1940s and 1950s. She does an excellent job with the period details with regard to fashion, never being showy about it but understanding the way people dressed and wore their hair. As I noted above, the best part of the book is when Nina is talking to her mother in the present, and the art is excellent in those periods, but this extends to Yugoslavia in the 1970s, where Nina does a nice job with the emotions of the participants without having to put them into words. Her imperious grandmother, especially, is drawn very well - she's a kind grandmother, but Nina draws her in such a way that we see the steel beneath and know why she is so angry about Peter's devotion to the dynasty. Bunjevac's art doesn't get bad during the "Peter's history" portion of the comic, but like the script, it doesn't soar in any way, either. She simply uses the pictures to back up the writing, and neither are that compelling.

I'm very bummed that I don't like Fatherland more, but such is life. It sounds a lot more interesting as a plot summary, but Bunjevac just doesn't do a particularly good job of telling the story. As a history, it exhibits the worst qualities of historical writing, taking a fascinating period and making it dry, while as a family memoir, it doesn't give us much insight into the family with which it is concerned. It's a shame, because I had high hopes for the book, but except for a few scenes and, you know, the fact that I didn't know about the terrorists operating on North American soil in the cause of Serbian nationalism, it doesn't work for me. Obviously, mine is just one opinion, and the very wise Sonia Harris, for instance, very much enjoyed the book. But that's what we do here - let you guys know about comics you might have missed, and you can make up your own mind!