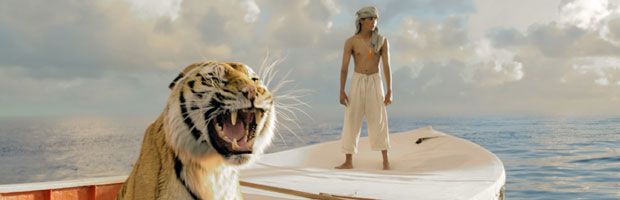

Yann Martel’s fantasy adventure novel Life of Pi was long considered unfilmable, largely because it centers on the relationship between a boy and a Bengal tiger trapped together on a lifeboat. It’s a cinematic, if not necessarily cinema-friendly, scenario.

"We're always told, 'Never make a movie featuring animals, kids, water, or 3D,’” director Ang Lee said last month during the premiere at the New York Film Festival. He hit the superfecta with his latest undertaking, though not just in theory: In its best moments, Life of Pi is an absolutely stunning celebration of the marriage between vision and substance. This is the director of Brokeback Mountain, The Ice Storm and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon most decidedly in his element – again exercising his prerogative to be as concerned with the intricacies of all that surrounds humanity as with humanity itself.

Lee wastes no time establishing his ability to explore childhood angst, confusion and wonder to brilliant effect with the film's buildup, which introduces us to adult Pi (Irrfan Khan), an Indian man living in Canada, who is visited by a writer (Rafe Spall) claiming Pi's uncle "said you have a story that will make me believe in God."

Pi narrates the tale of his early days growing up in Pondicherry, "the French Riviera of India,” where his pragmatic father (Adil Hussain) owns a zoo, his muscle-bound honorary uncle teaches him to swim, and the somewhat-lewd pronunciation of his full name Piscine (after one of France's most wondrous swimming pools) incites jeers and jokes from his schoolmates. We see young Pi (Ayush Tandon) overcome pre-teen adversity by seeking solace in the numerical metaphor of his self-given nickname, along with the transformative respite offered by religion. Pi soon finds himself enamored with, and actively practicing, Christianity, Hinduism and Islam.

Although his mother indulges his enthusiasm, his father laments, "Believing in everything at the same time is the same thing as not believing in anything at all." Pi's disenchantment with the magic of the world comes in the form of the zoo's Bengal tiger Richard Parker (in one of the many parallels between Pi and the massive cat that so entrances him, we're treated to a backstory regarding Richard's unusual name). When naive Pi attempts to feed Richard, he's caught by his father and shown the true nature of the beast. It's something that never leaves Pi as he gets older (this version portrayed by Suraj Sharma), although his fascination with Richard remains steadfast.

When Pi's father decides to move the family overseas, they're ushered onto a ship along with the contents of their zoo, until a storm interrupts the voyage, marooning Pi and Richard in a lifeboat in the middle of the Pacific.

The bulk of this film – its heart, soul and visual splendor – lies in the harrowing days man and animal are forced to survive together. It's also what serves as a reminder that big-studio movies can still be sparse yet surprising; character-driven and meaningful yet harrowing; deliberate yet never boring. Pi's faith and savvy is tested, and Richard – to Lee's great credit – is never humanized on an obvious level. There were four real-life tigers playing the part, but CG technology filled in many of the gaps. While the animal is undoubtedly emotive, and his relationship with Pi unfolds into faceted developments throughout their time together, we're still very much aware of the early lesson Pi's father wrenched upon him: Richard's humanity lies almost entirely in his human name.

To rewind for a moment, the film's shipwreck is an absolute marvel. The excellent sound design in Life of Pi is showcased to full effect, creating an overwhelming vortex of loud, crashing chaos into which Pi is wrenched. The spectacle is as disorienting for the audience as it is for the film's protagonist. We're confronted with the horror and claustrophobia of diving and being sucked into a narrow, flooded hallway as a zebra conversely floats from an open doorway. Pi clings to a railing and looks onto a deck beyond as crewmen are swept out to sea, an eerie glow cast from their flashlights the only indication of their whereabouts in the churning darkness. These images are as beautiful as they are terrifying – this is a sinking that gives Titanic a run for its money.

And that's only scratching the surface. For all intents and purposes, the bulk of Life of Pi is a one-location set, but Lee creates an environment of jaw-dropping magical realism and colorful, graphic intrigue. Almost every shot could be a screensaver or a billboard or a postcard – overhead images of illuminated plankton backlighting a whale as it swims below the dwarfed lifeboat, a deluge of flying fish barraging Pi and Richard, a side view of the boat blown out on a sunny horizon, underwater-to-above-water camera movements – as Lee leaves no angle unexplored with his location. It's a perfect canvas upon which to paint the film's themes of survival, trust, belief in a higher power and the tests of nature versus faith.

Newcomer Sharma is, frankly, a revelation as Pi. It's all in his eyes – often the expertly controlled emotions don't bubble beyond, but when they do, they're palpable. The fact that most of his scenes were acted out against nothing (Richard Parker was added in post-production) is a tribute to Lee's ability to coax his young actor, as well as Sharma's well-honed intuition. And, for the most part, Richard Parker is dually impressive. There are moments when the tiger's CGI strings show (when he's wet, for example), but they're fleeting. Where the technology truly falters is some of the undersea scenes, when darting fish and massive creatures alike are splashed across the screen to awe, but end up coming off as a big-screen version of a National Geographic channel recreation. The moments when the film shifts focus from its key players Pi and Richard – whether they prove quiet or combative – is when it falters.

Although I consider 3D unnecessary unless its function is innately interwoven in a film's premise (see last year's Hugo and Cave of Forgotten Dreams), the technology is incredibly effective when it comes to immersing the audience in certain moments (the shipwreck and flying fish scene are perfect examples). I don't necessarily think the 3D makes or breaks the film's visceral and emotional impact, but if you have a choice I'd tip the scales in 3D's favor.

Life of Pi is one of those films you'll find yourself immediately endeared to, visually and emotionally. You'll chew over its themes and scenarios long after you exit the theater, and some of the imagery is impossible to shake. While Lee is a filmmaker who hasn't always gotten it right in the past, he can be trusted upon to explore the heart of the matter – and Martel's novel gave him ample material with which to exercise the depth of his vision. Whatever your approach or takeaway, with Life of Pi Lee proves that subjectivity is reality, and he leads by example.

Life of Pi opens nationwide Nov. 21.