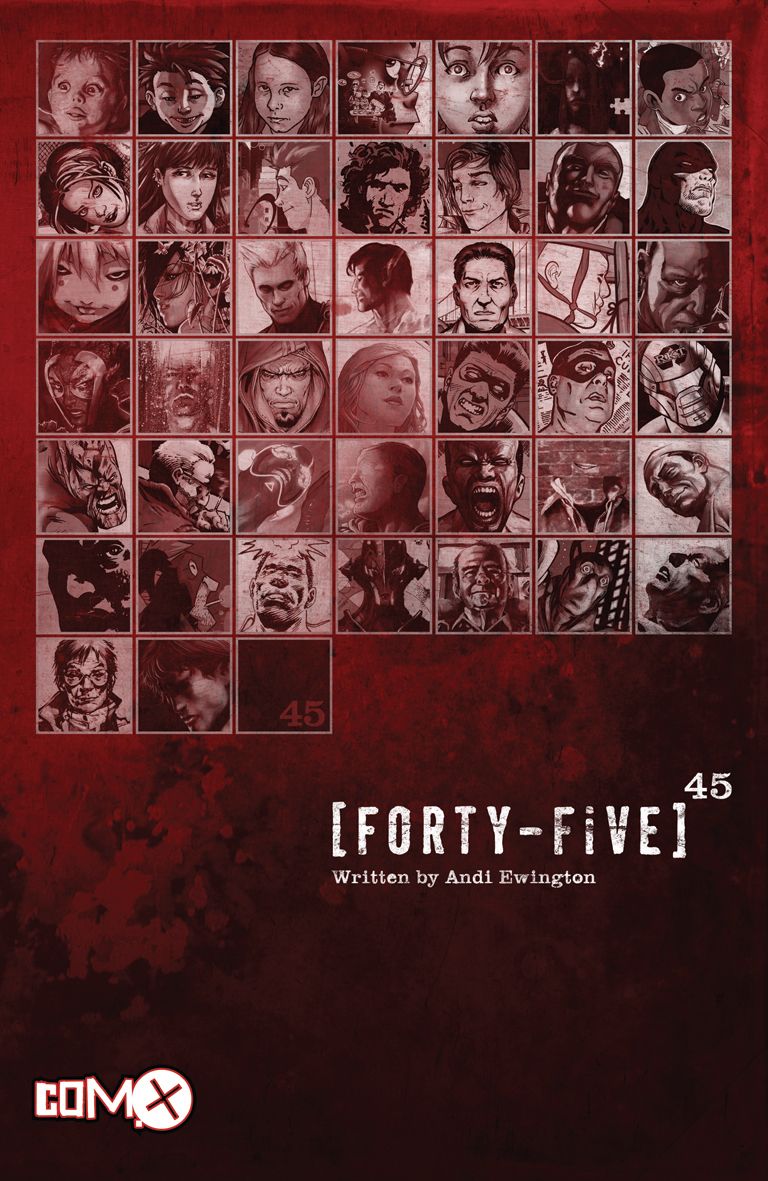

Com.X was nice enough to send me a copy of Forty-Five, a graphic novel (of sorts -- I'll talk about that) about a journalist interviewing various people with or close to people with superpowers. It's a text-based book with illustrations by 45 different artists. There will most likely be spoilers, but since there isn't exactly a plot per se, that shouldn't be too problematic.

Forty-Five by Andi Ewington, 45 artists, and 8 additional colourists.

I really like Q&A interviews. I own a few books that contain just them and they're usually a lot of fun to read. Especially books where there are numerous interview subjects that share a common thread. So, you'd think that Forty-Five would be right up my alley. I had heard of Forty-Five before receiving an e-mail from Com.X asking if I'd like a copy for reviewing purposes. The basic idea: a journalist conducts 45 interviews in a world where some people are born with superpowers, because his wife is pregnant and there's a chance his kid could be Super-S (as it's called there) and he wants to learn more about it. Each interview is a page long with an illustration by a different artist accompanying each interview. A nice broad concept with some interesting possibilities.

But, reading it, I don't think the book ever gets beyond that novel concept to anything deeper or interesting.

The structure, while interesting, is incredibly limiting. Limits aren't necessarily bad, but, here, they make reading the book something of a chore. A series of one-page interviews ordered by the age of the subject? That's a little too nice and tidy, a little too structured -- to the point where the interviews become less and less affecting within these limited confines. With only a page, there isn't a lot of room to deliver strong, deep interviews, so much so that it makes it hard to believe that the journalist, James Stanley, is actually good at his job. Maybe he isn't -- maybe that's the point. But, it does make for a lesser read. Keeping to that strict page structure gives most of the interviews their own set structure of introduction, fleshing out some superficial elements of their characters, and wrapping things up much too quickly. Sometimes, there are glimpses of what's deeper, but most of the interviews are much, much too brief to get beyond the surface. Stanley seems oddly contented to stay there as well.

One of the appeals of books of interviews is that they're free-ranging. There isn't a set limit. The best interviews last as long as they will. Some are short, some are long, but, here, they're all uniform and that seems forced. Some of the interviews work perfectly fine in a single page, like the first one where two parents discuss their child being Super-S a very short period after the birth. They're both excited and there isn't a lot to get at beneath what's covered. But, other interviews, like the ones with career superheroes, could span much more than a page and come off as truncated. Like 'greatest hits' versions of the real interviews with some 'big' questions and topics covered, but very perfunctory on the whole.

Part of the problem is that Ewington has to work with what's already there. Superhero stories have been around for decades. Stories focusing on the 'human' element have been around for a long time, too. He's operating with a subgenre that's been very exposed and doesn't really have anything new to say. Aside from changing some terms (villains being called 'Vaders') or establishing some different socio-political elements, there isn't much here that took me by surprise or gave me new insight. The same could be said for any number of superhero books, but since the point of this one is to give insight, to provide a unique window into what being Super-S is like, I expected more.

Ewington is playing more with conventions and reacting to what's there already. Jokes about how hard it is to find superhero names that haven't been used, for example, pop up a few times. There's a Thing stand-in whose marriage falls apart because they can't have sex or a Daredevil type that retires with dignity. He mentions the interplay of superheroes and the media somewhat. Or, draws an interesting distinction between Super-S heroes and 2nd Degree heroes (those that get powers through an accident or some external means) that I don't remember seeing drawn too much in other comics (aside from Marvel's focus on mutants, but that's different). He draws some attention to the downsides of being a hero: namely working for free, but only has an obviously shallow and arrogant character present the argument that it's not fair that superheroes should do the same jobs as soldiers or the police without pay or benefits. Again, it's a good idea that's only approached and handled in superficial terms.

One case that really stood out was one where the child of a Super-S is born and ages incredibly fast, dying of old age moments after it was born. Except the interview focuses on that as it happens when no real insight can be gained. It happens (and the illustration shows us it happening) and... what? It's an interesting idea, but one done before. The value of it would come out of how the parents react, how it affects their lives, from what happens next. As it stands, it's just a sad little story that doesn't tell us much beyond 'sometimes superpowers can suck.'

The ordering of the interviews really bothered me as well. They are ordered by the age of the Super-S (or 2nd degree, or other subject) and that doesn't present as compelling a look. I would have preferred they were ordered in the order in which James conducted them, which would allow us to see him build upon what he was previously told -- which he does, but it's hard to know during any given interview which ones he's already done. There's a subplot surrounding an American government organisation known as XoDOS as it comes up a lot -- it's basically a shady group that tries its best to employ Super-Ses and seems set on running things in the future. This subplot never gains any real traction because we're not sure how much James knows at any given point. And, if we're to believe that this is the order in which he conducted his interviews... well, that's just as problematic.

I like the idea of the interview/illustration structure, but found the illustrations distracting most of the time. They're presented on facing pages: drawing on the left, interview on the right, and, often, the drawing would showcase a key element from the interview, colouring my perception of it when I read it. It got so frustrating that I was tempted to rip the book apart so I could just read the interviews and look at the illustrations on their own. There's nothing wrong with the drawings by themselves, but I would have preferred to have the interviews stand alone. The drawings feature a lot of talented people like Sean Phillips, Charlie Adlard, Dan Brereton, Simon Coleby, John Higgins, Jock... the list goes on. Obviously, not every picture is amazing, but the overall quality is high. One thing I really liked was that not every illustration is a single picture. Many artists used panels to tell a story, which was unexpected and inventive.

The question that was raised when Tim Callahan and I were discussing this book was if it's a comic at all. He argues no since it's a text piece that happens to have illustrations added and I'm inclined to agree. Once you look at the book that way, it becomes more and more apparent that its current presentation holds it back quite a bit. Instead of delivering longer, more insightful interviews, something possibly akin to Haruki Murakami's Underground, for example, it's trapped in this set format. I think if it were given more room to breathe and allow us inside the lives of these characters even more, it would be much stronger. Maybe that's unfair since that's not the project here -- but that's all I could think as I read it.

If anything, Forty-Five reads like a template, an idea generator -- a place for others to come, take what's here and build upon it to craft better, more engaging stories than what Ewington has written. The structure is so limiting that it's no wonder that the book is all surface. The idea behind the book has a lot of potential, but the execution is underwhelming and frustratingly simple.