As a lifelong comics reader and a woman who identifies as a feminist, there have been plenty of times where the disparity between what I believe in and what I love has caused me heartache. While there have always been women in comics, both as characters and working as industry professionals, the quality of representation hasn't been consistent. Sometimes, it hasn't even been present. Sometimes, its presence has been an echo of the problematic points of view in the real world, reminding me that my gender is frequently, aggressively misunderstood by the industry I love. Lately, we've seen the world (both inside and outside of comics) demonstrate a sickening hostility toward women, one that makes me want to escape into a fantasy world where everything is okay. And while, no, the world of comics isn't perfect, there are some amazing examples of feminism within it. There are creators that get it, who inspire me, give me hope and show me how much I matter as a reader -- and those examples are to be celebrated right here.

But first, let me define how I'm using "feminist" in this article and in my selection process. When I think about feminism, the word that comes to mind is "choice." To me, feminism is empowerment and advocacy for women to make our own choices. This means we have diverse lifestyles, gender identities, points of view, physical characteristics, desires and motivations -- and those need to be represented authentically and without judgment.

For me, a feminist comic is one in which female characters aren't just a plot device providing male characters with an opportunity to react. They aren't a thing to be rescued, fucked, killed and discarded. Feminist comics show women as people, not tits and ass whose stories are only interesting if they're sexy. Their physical representation should be reflective of their character in a way that makes sense. The way they dress, how their bodies are portrayed -- these things aren't just to entice, but to inform. I have nothing against demonstrations of sexuality, and don't feel a 'good feminist comic' means the boobs are covered, but when a female character is sexualized, it should be relevant to who she is. She should have a story, a purpose and a narrative that portrays her as more than a victim or an object of desire.

Below, I present fifteen of my favorite feminist comics, a list curated with love. I encourage you to read with curiosity and to challenge your perceptions about what has been the status quo for women in comics. Mostly, I hope you pass this around and add your own favorites to it. After all, we're a community.

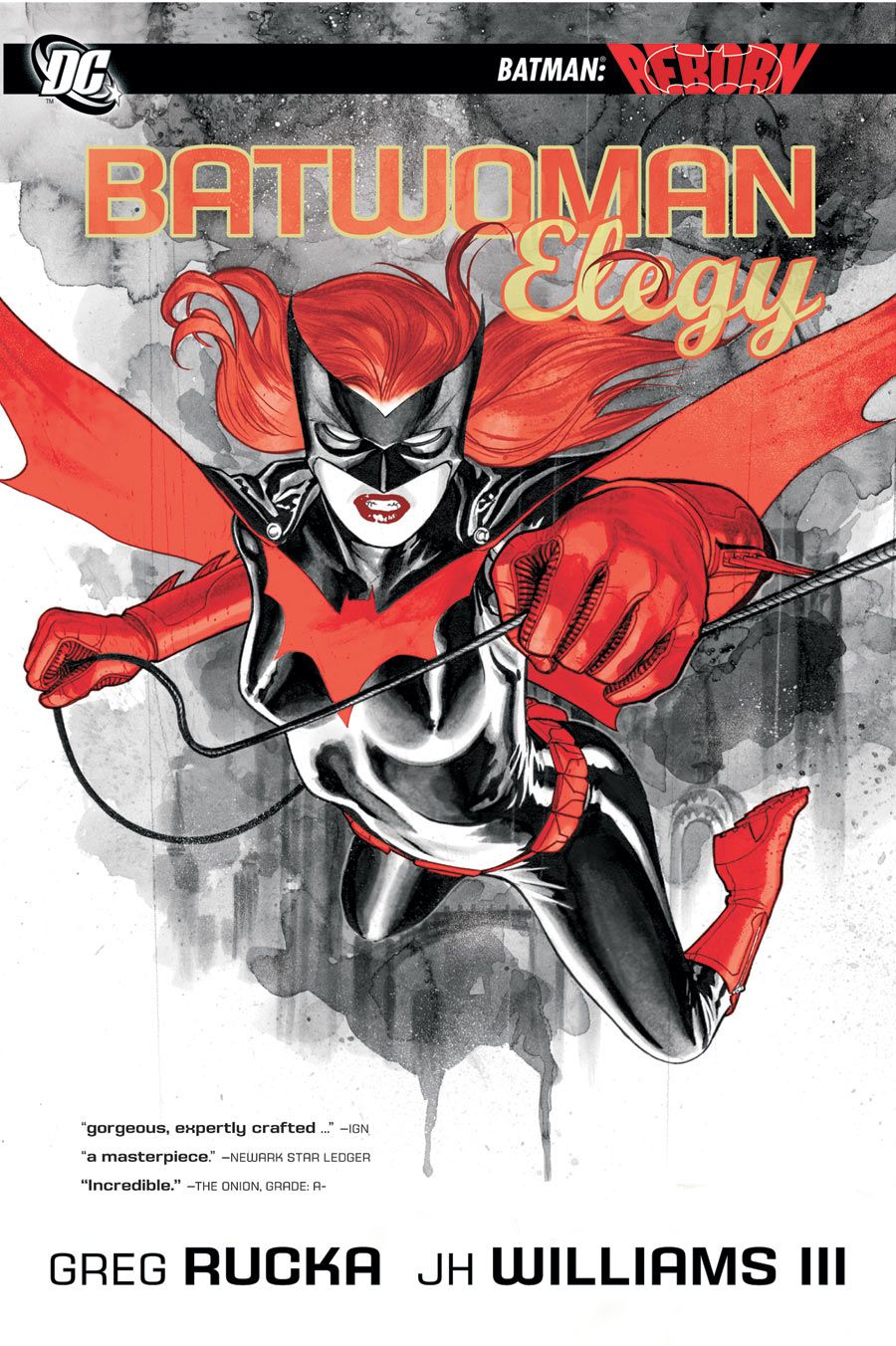

"Batwoman: Elegy" by Greg Rucka and J.H. Williams III

This title is frequently celebrated for being an exquisite example of both diversity and feminism in comics, and Rucka is one of the finest writers in the industry when it comes to penning grounded female characters. His run on "Batwoman" was no exception. Kate Kane took over as Batwoman after Batman was presumed dead in "Final Crisis," with "Elegy" beginning just a few months later. A lesser creator might've felt the need to sprinkle in a basic, boring dose of gender politics, focusing on the perceived obstacle of her femaleness -- but Rucka doesn't do that. He treats Kate with respect, introducing her identity as a lesbian early on but never using her relationships as easy fodder for drama. It isn't even until the end of "Elegy" that you realize just how powerful Kate's sexual identity is, when she rejects an opportunity that would've forced her into the closet. In the Bat Family, personal lives rarely supersede the calling for vigilante justice -- but not with Kate. Rucka's Batwoman respects herself as much as the title, refusing to separate her identity as a woman from her identity as a Bat.

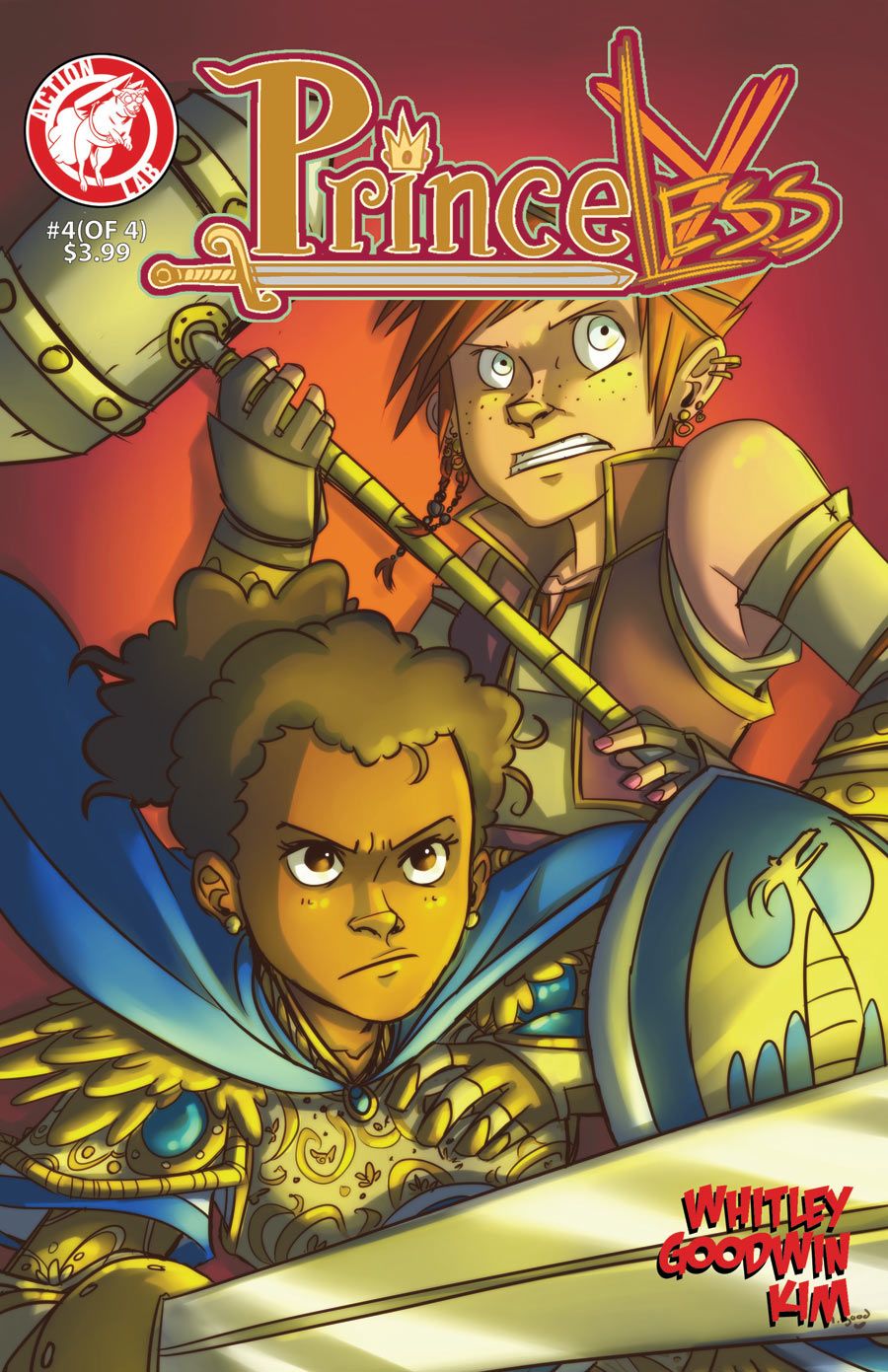

"Princeless" by Jeremy Whitley and M. Goodwin

Princess Adrienne is tired of waiting to be rescued. Unimpressed with the whole imprisoned-in-a-tower thing, she decides to set off -- along with her dragon -- to have her own adventures, starting with freeing her five sisters from their towers. Not only is this book all-ages, but it features a cast with women of color in leading roles. Most of the first arc is dedicated to Adrienne saving herself, which with a lesser creative team could be impossibly cheesy, but Whitley's sharp, sarcastic writing keeps "Princeless" fun and relatable.

"Rat Queens" by Kurtis J. Wiebe and Roc Upchurch

Hannah, Dee, Betty and Violet are the best sword wielding, spell casting, squid-god worshiping, mercenary girl-gang in all of Palisades. From the very first issue, I knew this book was special. Not only does it play in the world of "Dungeons and Dragons" humor with insider wit and knowledge, but Wiebe and Upchurch have created holistic bonds between the characters that speak to a well-thought out story. Upchurch's artwork is expressive with each character, from the studly Captain of the Guard, to the filler orcs, to the Queens themselves, uniquely designed, showcasing a wide variety of body types. The book approaches sexuality of its cast with respect. Betty is a lesbian whose relationship isn't a source of titillation, but an authentic expression of who she is. Violet and Hannah both have steamy flings with men who don't challenge their power, but are attracted to it. "Rat Queens" does every single thing right, including inspiring a line of merchandise designed to actually fit women's bodies.

"Sex Criminals" by Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky

Yes -- the most accurate comic about a teenage girl coming of age and growing into a sexually expressive woman who can stop time when she has an orgasm was created by two men. And they absolutely nail it. This series approaches relationships and sex with genuine tenderness, layering in magnificent filthy humor and plenty of dildo fights. The talented Zdarsky uses models as photo references for the art, resulting in a realism to his characters' bodies that makes them crackle with chemistry. The honesty in "Sex Criminals" takes many forms, from a young Suzie being slut-shamed by her mom for asking questions about sex, to her incredibly unhelpful doctor policing her body, to the discovery of woods porn, to the Dirty Girls in junior high who educate young Suzie about the joys of brimping.

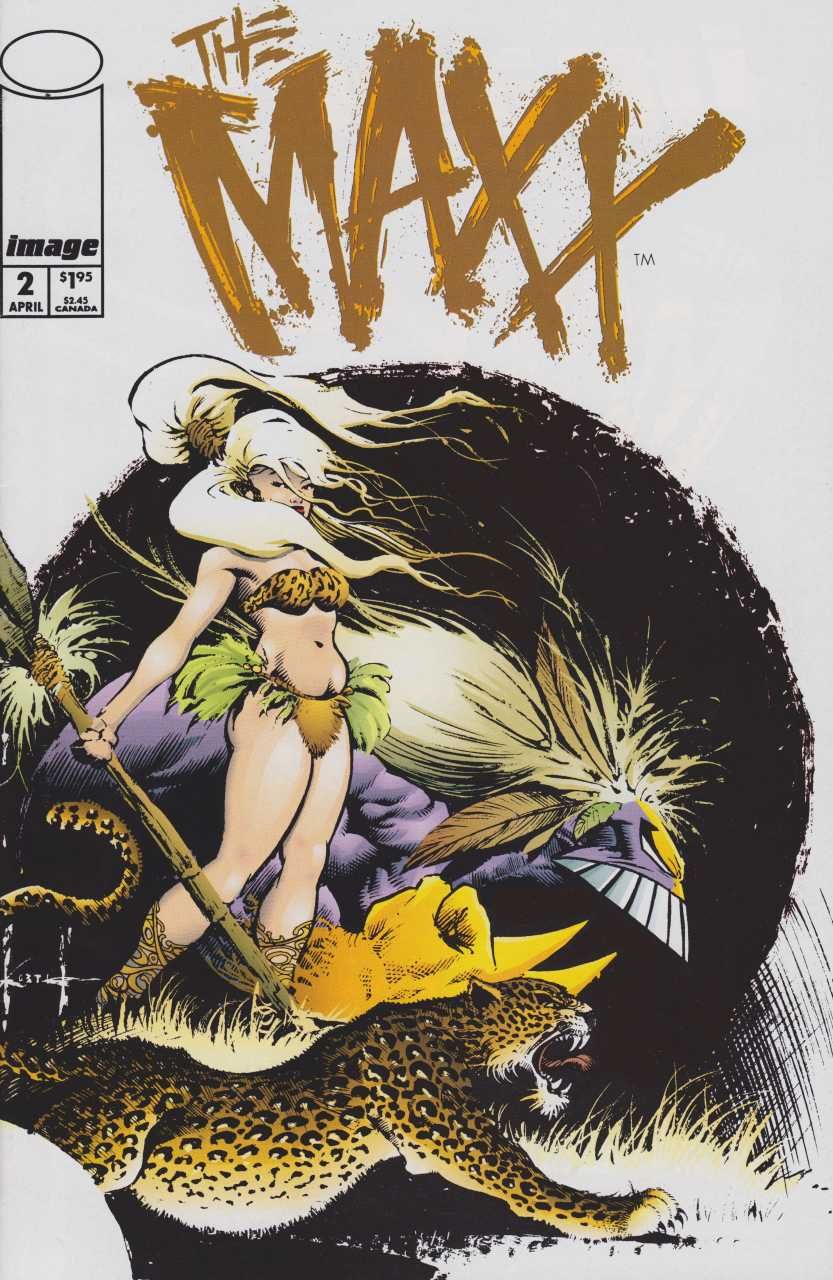

"The Maxx" by Sam Kieth

Julie Winters is a freelance social worker who not only refuses to be classified as a feminist, she's openly disdainful of the title, sparking some interesting ideas about her disassociation and her actions, all of which are incredibly female-positive. Although her tough demeanor is a self-defense mechanism stemming from sexual assault, Kieth never uses rape to define Julie's character, as other, lazier writers might. Instead, he created an even deeper, darker backstory. Julie copes with her pain by retreating into a fantasy world where she is the Jungle Queen, a beautiful, solitary, powerful creature in total control. This world, The Outback, is so compelling that it actually creates the foundation for most of the first arc, including the origin of the Maxx himself.

"Captain Marvel" by Kelly Sue DeConnick

As part of DeConnick's "Captain Marvel" run, the writer introduced a time-travel paradox that allows Carol Danvers to be the source of her own power, disrupting her former origin story and setting the tone for the rest of the series. With so many female superhero origin stories rooted in accidents or victimization, Carol's reinforces a belief in self-sufficiency. DeConnick traded in the "Ms" title for "Captain," and Jamie McKelvie was commissioned to design a new costume which is befitting her rank. Gone is the impractical swimsuit, and in its place is a flight suit which embodies the bold, capable nature of Carol's character.

"Lumberjanes" by Grace Ellis, Noelle Stevenson, Brooke Allen and Shannon Watters

An all-female team writing a book with an all-female (so far) cast? Yes, please! "Lumberjanes" is only two issues deep, but it's made a huge impression on me. It's a rough-and-tumble story following the summer camp adventures of teenage Lumberjane Scouts Mal, Jo, April, Molly and Ripley. The tone is reminiscent of "Adventure Time" and "Powerpuff Girls," maintaining high action and clever dialogue. I can't wait to see what the creative team has in store for the rest of the series.

"Hark! A Vagrant" by Kate Beaton

This simple, strip-based humor comic takes classic literature tropes stepped in sexism and flips them on their heads. Beaton roots for the ladies of books like "Jane Eyre," "The Great Gatsby" and "The Secret Garden" while pointing out the ridiculous patriarchal spaces they inhabit, making us laugh while reconsidering the canon.

"Saga" by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples

There are so many things "Saga" does well -- body type diversity, prominent female characters, characters of color -- but to me, the comic's most unique quality is how Vaughan and Staples depict motherhood. If you are unfamiliar with the series, it follows the forbidden relationship between Marko and Alana, two people from opposing races whose planets have been at war, as they fight for freedom for themselves and their young daughter, Hazel. Alana is a warrior and a woman of power. She doesn't go through an improbable personality shift as she becomes a mother, eschewing her boldness and morphing into a sweet matriarch, but maintains her surly, sexy demeanor. In fact, check the cover of the first issue where she's breast feeding while holding a gun. And then just keep reading, because it only gets better.

"I Kill Giants" by Joe Kelly and J.M. Ken Niimura

Barbara Thorson deals with the pain, fear and awkwardness of coming of age by doing what most fifth grade girls do: Slaying giants with a big ol' hammer. An unlikely protagonist, Barbara is anti-social, bitter, judgmental and, at times, difficult to root for. She retreats into a fantasy world to escape, cocooning herself in power, control and solitude. The reveal behind what Barbara is escaping plays out with excellent pacing and a sense of respect for the circumstances, when Kelly and Niimura could've easily pandered to audiences. Also worth mentioning: Barbara wears bunny ears. Like, all of the time.

"Death: The High Cost of Living" by Neil Gaiman and Chris Bachalo

Gaiman's Death was arguably the most popular female comics character of the '90s. She was so beloved, she starred in her own miniseries, following Death/Dee-Dee as she becomes mortal for a day to learn the value of the lives she takes. Although the main character in the series is a man, the story is driven by Death as she blithely explores the modern world. Along the way, she meets a diverse group of women who are atypical for comics, including a lesbian couple expecting a baby. While the entire "Sandman" series is an excellent feminist comic, Death's story is my favorite, and nowhere are her charms more relatable than this miniseries.

"Anya's Ghost" by Vera Brosgol

In "Anya's Ghost," Brosgol perfectly captures the feeling of being a teenager. The mundane life where everything is yet somehow critically important, the agonizing relationship with body image, the horrendous embarrassment about parents. On top of the standard barrage of teen horrors, Brosgol's protagonist Anya is a first-generation Russian immigrant who desperately wants to fit in with the other kids at her private high school, but in spite of her best efforts always finds herself an outsider. Anya's loneliness motivates her to befriend the ghost of a young girl she meets -- Emily -- who seems nice at first, but is soon encouraging Anya to live dangerously. When it becomes clear that Emily doesn't have Anya's best interests in mind, guess who stands up for her? She does. Anya isn't saved by her parents or a boy or her friends; she solves her own problems, including escaping a murderous ghost.

"Red Sonja" by Gail Simone

Simone began her run on this series last year, reclaiming a character that had long suffered at the hands of indelicate storytelling, often relegating her to just another babe in armor. Simone's She-Devil is lusty, clever, ferocious and wild, making her first appearance in the series passed out drunk at a campfire. This isn't to say that Simone writes her female barbarian like a man with breasts, because it's quite the opposite -- Red Sonja is both feminine and bloodthirsty, with an edge of humor that keeps her infinitely likable.

"Persepolis" by Marjane Satrapi

This biographical story of Satrapi's experience during the Iranian revolution sees the writer grow from girlhood to adulthood as she travels between the Middle East and Europe, trying to find her home. Satrapi's voice as an Iranian woman exploring her relationship to her body, her faith and her critique of Western involvement in her country's political unrest is both gentle and sharp, inviting readers to understand her perspective. Written largely for Western audiences whose prejudices might prevent them from viewing Islamic women clearly, Satrapi shares stories of her mother, who encouraged her to become an independent, cultured and educated person, even while acknowledging the misogyny present in their society. Satrapi's voice doesn't just humanize the women of Iran, it also reminds us of the civilian cost of war and the plight of all women struggling under repressive governments all over the world.

"Locas: The Maggie and Hopey Stories" by Jaime Hernandez

While all of "Love and Rockets" is a wonderful example of feminism in comics, the carved-out stories of Maggie and Hopey remain some of my favorite. "Locas" follows the relationship between two feisty, intelligent, punk rock ladies who drift from lovers to friends over the course of fifteen years, challenging authority and exploring class, gender and race issues in stories infused with Hernandez's signature charm.

Other notable titles include "Pretty Deadly" by Kelly Sue DeConnick and Emma Rios, "Lazarus" by Greg Rucka and Michael Lark, "This One Summer" by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, "Umbral" by Antony Johnston and Christopher Mitten and assorted "She-Hulk" comics (the ones where she's not being a giant green porn star, obviously).