The National Coalition Against Censorship has written to Lee Ann Lowder, deputy counsel for the Board of Education of Chicago, questioning the school district's authority to remove Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis from seventh-grade classrooms. The letter is signed by NCAC Executive Director Joan Bertin and Comic Book Legal Defense Fund Executive Director Charles Brownstein, as well as representatives from PEN American Center, the National Council of Teachers of English, and other organizations. I don't usually find myself on the opposite side of an issue from these folks, but my own opinion is that this case has been overblown.

Here's the backstory: On March 14, employees showed up at Chicago's Lane Tech to physically remove Persepolis from classrooms and the library and ensure no one had checked out any copies. This seemed sinister, to say the least, and word spread literally overnight. As parents planned a protest on March 15, Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett backtracked and said the book was to be removed from seventh-grade classrooms but not from school libraries. Byrd-Bennett said the district would develop guidelines for teaching the book to juniors and seniors, and possibly in grades eight through 10 as well, but it's not clear whether the books also were removed from those classrooms.

I think the issue here is really not the removal of Persepolis but rather the way the Chicago Public Schools handled it.

There is a difference between removing a book from the library and not making it mandatory classroom reading, which is what happened here. In our Good Comics for Kids discussion, Esther Keller, who's a middle-school librarian said this:

My gut tells me that this isn’t a title for 7th grade. I remind you, I’ve been working in a middle school for 10 years now. I might not be an expert, but I do know the age well. They’re not all that mature. And while I wouldn’t exclude it from a school library, I don’t know that it’s an appropriate classroom choice.

Keller's point is an important one. As a professional, she makes choices as to what to include and exclude. That's what educators do. Are the Chicago Public Schools violating the First Amendment by not teaching MPD-Psycho to seventh-graders? No, they are not. There's a whole universe of books that aren't being taught to Chicago seventh-graders right now. It's the school district's job to make choices. What attracted attention here is that they changed their minds and, having changed their minds, they handled it badly.

The NCAC's letter begins by questioning whether the Chicago Public Schools have the authority to remove Persepolis from classrooms. The letter juxtaposes two Supreme Court decisions, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette and Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, arguing that the first case compels boards of education to respect the First Amendment, and the second emphasizes that government cannot restrict expression because the content is objectionable.

The two cases are apples and oranges, though. Barnette was about whether a school district could compel a student to say the Pledge of Allegiance (answer: no). The question in Brown, on the other hand, was whether retailers could be required by the state to prohibit minors from buying or renting violent video games. In that case, the government is an outside enforcer interfering in a private transaction, as it would be if it were trying to get Persepolis removed from local bookstores. But the Chicago Public Schools weren't taking books away from kids, and in fact, they kept them in the school libraries (although this was a reversal of an earlier mandate). They simply stopped teaching the book in seventh-grade classrooms.

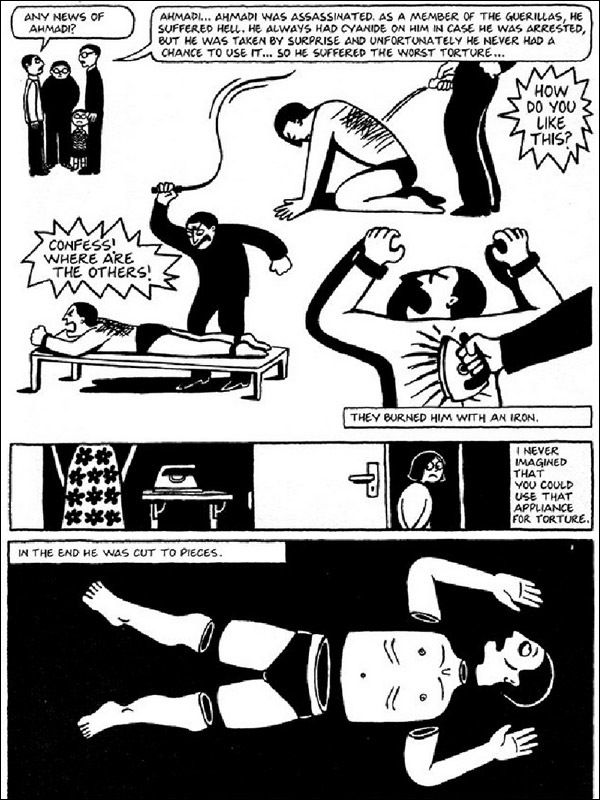

The letter makes a number of arguments about how fairy tales are violent too, and that violent imagery should be included in curricula, and there's a separate rationale for including Persepolis in the curriculum, which is all well and good, but at the end of the day, it's all about choices, and it's the educators' job to make those choices. No one is saying Persepolis should not be taught at all; what the school district is saying is that administrators don't think it should be taught to seventh-graders. That they reversed a previous determination makes for bad PR, but at the end of the day, nobody's rights were taken away.

In fact, let's flip this around and ask whether school curricula should be determined by outside organizations such as the NCAC and the CBLDF. Because basically, they are introducing a political agenda into the schools by trying to overrule school administrators. It's the NCAC's job to fight censorship, yes, and I salute its defenses of library challenges, but this is not that. This is an outside group trying to dictate curriculum in opposition to educators. Do you think that's a good idea? A couple of years ago, a ballot question banned bilingual education in Massachusetts. Because we haven't had any ballot questions on the new math or whole language vs. phonics reading instruction, it's hard to deny that at least some voters had a political rather than educational agenda in mind. In the end, the dropout rate is up but other academic measures have remained constant, so regardless of intentions, it harmed some students and didn't benefit the others much. Politics and academics don't mix.

However, it is true that a school system should be at least somewhat transparent to the public it serves. I think it's entirely legitimate to ask how the decision was made. After all, there's nothing sinister about a curriculum specialist in an office choosing one book over another, but when someone shows up at your school, unannounced and with no explanation, and demands every copy of a given book — that's just creepy, and it's not surprising that people reacted the way they did.

There's an underlying suspicion here, implied but never overtly stated, that there was a single individual behind the abrupt removal of Persepolis. Perhaps a child was upset by the book or a parent felt their child wasn't ready for it. That's a poor basis for a library challenge but perhaps a better one for a classroom challenge; it's one thing to make a book unavailable to everyone because someone didn't like it, but another thing not to make a captive audience read a book that at least some children find upsetting. That's why Keller's point is so important. She works with seventh-graders all the the time, and she knows that some of her students wouldn't be able to handle the book. That seems to me like a good reason not to teach the book in seventh grade, but to hold off until a later grade while still making it available in the library.

I think the NCAC is right to ask for an explanation, but I'm not sure the group will get one, or for that matter, what purpose it would serve. An internal administrators' meeting isn't like a board or commission meeting where minutes are taken. The notes and e-mails the NCAC is looking for may simply not exist. Trust me, the people in the back office know a mistake was made, and they are likely to be more careful next time. To my mind, the school district's chief sin was a lack of communication. If it had waited until the end of the school year to change the book, or if it had explained to teachers and principals why Persepolis was being removed, the incident would most likely have attracted little attention.