No sooner did last year's epidemic of clown sightings subside than the menacing figure has returned with a vengeance, with a new adaptation of Stephen King's It setting box-office records, a band of rubber mask-wearing killers stalking FX's American Horror Story: Cult, and Warner Bros. reportedly considering no fewer than four films featuring The Joker. The balloon-blowing, confetti-throwing entertainer of circuses and children's parties has once more tightened its white-gloved grip on our collective consciousness, and on our nightmares.

IT REVIEW: Come For the Scary Clown, Stay For the Superb Cast of Kids

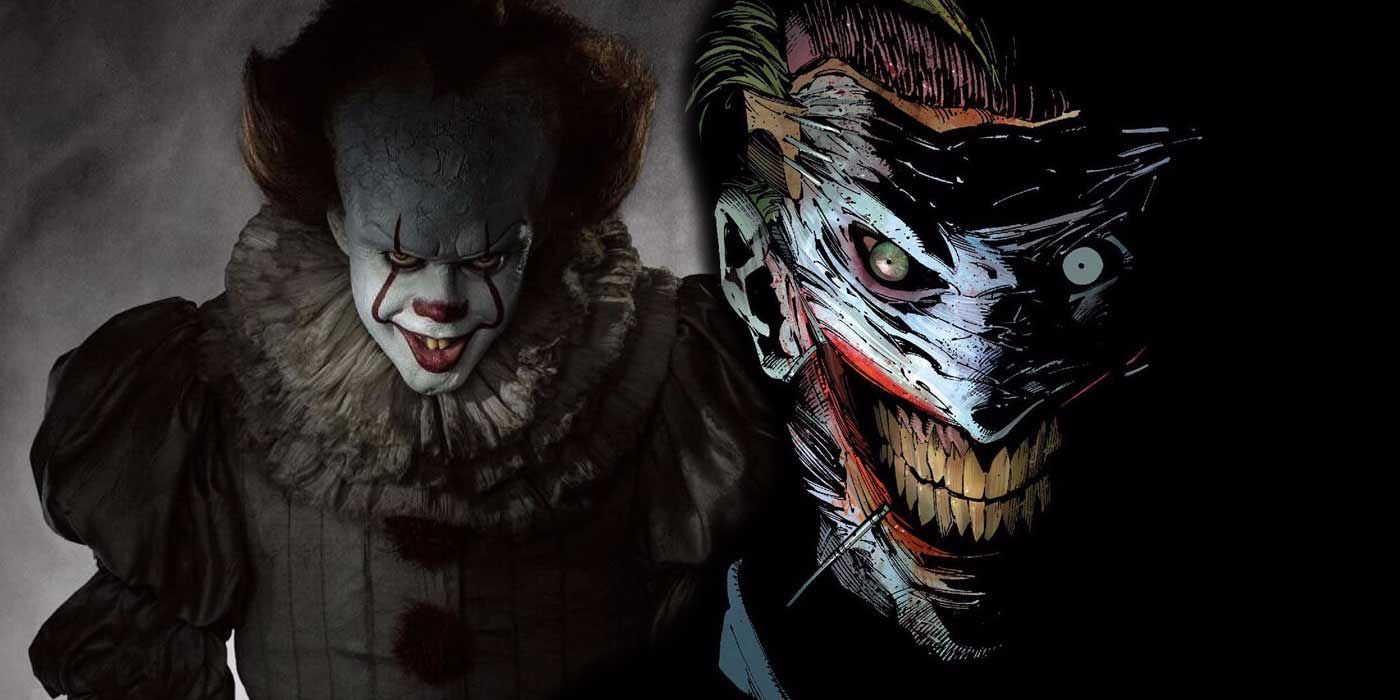

But what is it about clowns that simultaneously amuses and terrifies us, and why do characters like Pennywise and The Joker both attract and repel us, time and again, on the page and on the screen?

A study of more than 250 children conducted in 2008 by the University of Sheffield famously found that hospitals that decorate wards with paintings of clowns with the intent of soothing young patients may actually do the opposite. "We found that clowns are universally disliked by children," researcher Penny Curtis told BBC News. "Some found them quite frightening and unknowable." Subsequent studies raised doubts about those findings, suggesting that therapy clowns may actually ease the anxiety and speed the recovery of child patients.

That apparent disagreement highlights society's own contradictory relationship with clowns. It's perfectly encapsulated in the classic Simpsons episode "Lisa's First Word," in which a young Bart, who idolizes Krusty the Clown, is nevertheless traumatized when forced to give up his crib in favor of a custom-made clown bed: "Can't sleep! Clown will eat me!"

"A clown is funny in the circus ring," horror-movie legend Lon Chaney is said to have once observed. "But what would be the normal reaction to opening a door at midnight, and finding the same clown standing there in the moonlight?" That quote is echoed, whether intentionally or not, in the 1989 film Batman by Jack Nicholson's Joker, who asks, "You ever dance with the devil in the pale moonlight? I always ask that of all my prey."

Chaney, who played a clown on screen more than once (He Who Gets Slapped, Laugh, Clown, Laugh), touched upon an age-old dichotomy: The clown wears a makeup that masks his true identity and emotions, making him inscrutable. He's a liminal figure, not bound by the rules of society, allowing him to exhibit behavior that would get virtually anyone else in trouble. Even at his most subdued, a clown is wildly unpredictable, as likely to throw a cream pie as he is to perform a prat fall.

RELATED: The Joker Should Never Get An Origin Story, in the Movies or Otherwise

That freedom has been enjoyed for thousands of years, dating back to the royal courts of ancient Egypt and China. Although the word "clown," meaning something akin to a boor, didn't enter the language until the mid-16th century, jesters and fools have long enjoyed license to interrupt solemn rituals and publicly mock rulers, acts that might otherwise result in the execution of the offender.

A familiar figure begins to emerge in the late 16th and early 17th centuries with the stage character the Harlequin, and with it the earliest indications of a malevolent nature. "The crude, chaotic Harlequin character (typically wearing a mask and a colorful, diamond-patterned costume) is clearly a clown," author Benjamin Radford writes in his 2016 book Bad Clowns, "but his roots run sinister, as there is a link between him and the diabolical world." The name is associated in legend with the French version of the Wild Hunt, a troop of demons led by the black-masked emissary of the devil, the hellequin, which roamed the countryside, chasing the souls of the damned to hell. The theatrical Harlequin was, in Radford's words, a "diabolical, itinerant trickster," who became paired in the British harlequinade with the buffoonish Clown. (The Harlequin's name and garb, to say nothing of his mercurial disposition, were of course key influences in the creation Harley Quinn, The Joker's sidekick turned hit DC Comics franchise.)

Developing virtually parallel to the Harlequin, the Punch and Judy puppet shows have entertained British audiences -- children, no less! -- for centuries, starring a jester-like serial killer and his often-abused wife. It's easy to detect in them a foreshadowing of the relationship between The Joker and Harley Quinn; there's a black heart whose beat is obscured by over-the-top violence and a thick layer of greasepaint.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='Joker%2C%20the%20Man%20Who%20Laughs']

Joker, the Man Who Laughs

However, that darkness surfaced in the early 19th century with English actor Joseph Grimaldi. The first fully recognizable ancestor of the modern clown, the animated Grimaldi wore full makeup and colorful costumes on stage, where he was famed for his physical, and often violent, slapstick comedy. Off stage, he led an unbelievably tragic life, marked by childhood abuse, depression, the death of his wife in childbirth, and the loss of an adult son (a clown who drank himself to death); Grimaldi died penniless. With the posthumous release of Grimaldi's memoirs, edited by Charles Dickens, the image of humor being used to mask something dark took hold. That was certainly only cemented in 1892 with the premiere of the Italian opera Pagliacci (literally, "Clowns"), in which the main character murders his unfaithful wife onstage.

Those shadows remained as the clown immigrated with the circus to the United States, which gave rise to characters as diverse as Emmett Kelly's Weary Willie, Bozo the Clown, Howdy Doody's unspeaking partner Clarabell, Ronald McDonald and, yes, The Joker.

Inspired in part by the 1928 silent horror film The Man Who Laughs, the Clown Prince of Crime was introduced in 1940 in Batman #1. The Dark Knight's arch-nemesis, The Joker embodies all of the best (or worst) elements of the clown, stretching back to the Harlequin and beyond. He's the trickster, the serial killer, the agent of chaos. With his green hair, white skin and red permanent smile, he presents an almost comic, yet undeniably unsettling, facade; in recent years he even had his face removed and then reattached as a mask, adding another layer to his inscrutability, and his creepiness. Despite repeated attempts to tell The Joker's backstory, in comics and on film, he's resisted a definitive origin. "Sometimes I remember it one way, sometimes another," he says in 1988's Batman: The Killing Joke. "If I'm going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!"

RELATED: Alan Moore Insists He's Not the Northampton Clown

“Where there is mystery, it’s supposed there must be evil," Andrew McConnell Stott, author of The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi, told Smithsonian Magazine, "so we think, ‘What are you hiding?’”

Of course, that doesn't apply to fictional killer clowns, like The Joker and Mr. Punch, but to those in real life. The most famous is John Wayne Gacy, who in the late 1970s appeared at children's parties as Pogo the Clown, even as he was secretly raping and killing teenage boys and young men, and burying most of the bodies in the crawl space of his home. It was with Gacy, according to psychology professor Frank T. McAndrew, that "the connection between clowns and dangerous psychopathic behavior became forever fixed in the collective unconscious of Americans."

It was with Gacy's 1980 conviction for 12 of the at least 33 murders fresh in a nation's mind that Tobe Hooper and Steven Spielberg released 1982's Poltergeist, with its attacking clown doll, and Stephen King published his 1986 horror novel It, in which a supernatural entity terrorized the children of a small town in the form of the clown Pennywise. Despite decades worth of fictional killer clowns in film and television, from Killer Clowns from Outer Space and Carnival of Souls to American Horror Story: Freak Show and Killjoy, it's Pennywise who looms largest in our nightmares.

That's in no small part due to the 1990 television adaptation that starred Tim Curry as the malevolent clown, which was viewed by nearly 18 million households and an untold number of children and teenagers (unlike the R-rated It film, now in theaters, the TV miniseries bore no restrictions that might limit its exposure to a younger audience). If Gacy and the inherent disconcerting nature of clowns hadn't already scarred generations, then It certainly did, leaving us with unforgettable images of Curry's Pennywise holding balloons, peering out from a sewer grate or from between sheets hanging from a clothesline. And while "phantom clown" sightings predate the release of either King's novel or its 1990 adaptation -- the first such wave in the United States dates back to at least 1981 -- the resurgence last fall was bound to evoke haunted memories of It.

RELATED: Stephen King Was Surprised How Good the It Film Is

“The clown furor will pass, as these things do," King told the Bangalor (Maine) Daily News last fall, at the height of the clown sightings, "but it will come back, because under the right circumstances, clowns really can be terrifying.”

It's not necessarily an irrational fear, either (coulrophobia isn't recognized as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association).

"Being afraid of a clown making balloon dogs at a circus is a clown phobia; being afraid of that same clown sadistically twisting a live dachshund into a grotesque, furry tube of spine and dripping gore is not," Radford writes in Bad Clowns. "There is nothing at all odd, pathological, or unreasonable about fearing a clown chasing you with a gun or a meat cleaver."

Or, as King himself noted, "If I saw a clown lurking under a lonely bridge (or peering up at me from a sewer grate, with or without balloons), I’d be scared, too.”