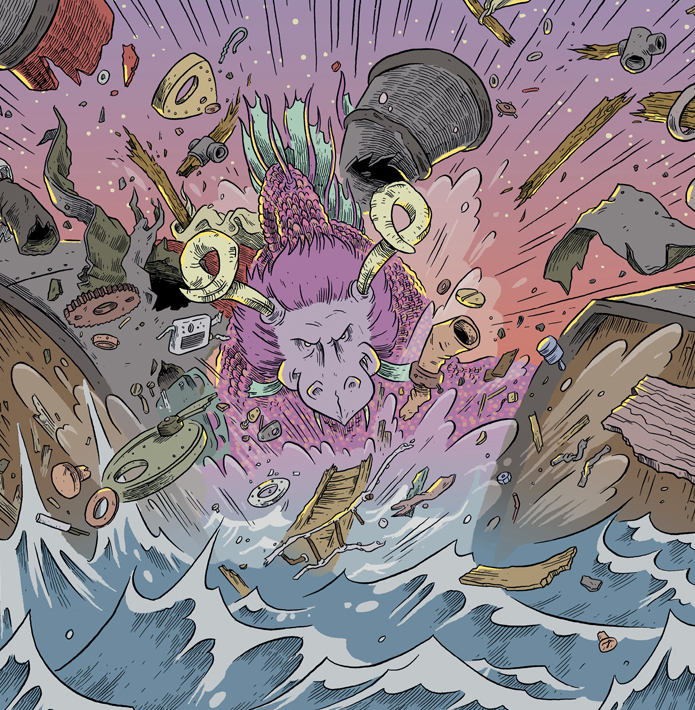

After four years and an Eisner nomination, Ben Towles' Oyster War is coming to an end. The webomic is based on an obscure chapter in American history, in which oyster pirates and legal fishermen fought over the rights to the harvest in Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac River. (Apparently, oysters used to be much larger and way cheaper before overfishing devastated the entire industry.) Don't expect a straight history lesson, however: Towles' version is visually more cartoon; he also embellishes his story with some fantastical elements, like a witch who turns into a seal, and a sea monster.

The old-school aesthetic of Oyster War recalls a style popular during the early 20th century, and the seaside town of Blood's Haven, with its narrow corridors and piers that stretch past the shore, resembles Thimble Theatre's Sweethaven. While backgrounds are simple and minimalistic, close-ups are lovingly textured. The characters are simple cartoony designs: bulbous noses, brush-like mustaches, block-shaped heads and stocky bodies.

Blood's Haven's entire economy revolves around oysters -- the harvest brings in the cash, and shucked shells create more land to develop. But pirates are starting to cut into the fragile ecology; a sailor named Treacher Fink is using an illegal oyster dredge to scoop massive quantities of oysters from the sea bed.

Enter Commander Bulloch, a grumpy former Confederate officer who's given the noble task of recruiting an Oyster Navy to bring an end to the pirate menace. He's a good choice, as he's a capable leader who recognizes resourcefulness when he sees it. Unfortunately, he's also given a limited budget that will only permit a rusty paddle wheeler and a ragtag (yet multicultural) crew. Most sport gray hair; they're "a bit long in the tooth," as Bulloch says. This motley crew is full of surprises, however, as a pirate attack is effortlessly repelled through the generous application of fisticuffs. The crewmen have other valuable qualities as well: A practical man and rational thinker, Bulloch's biggest blind spot is that he doesn't believe in magic, which leaves him stymied by the mystical unknown. Fortunately, there's someone on his crew who does believe, giving the Oyster Navy a crucial advantage.

Towles has a confident sense of pacing, and finds magic in laying out the methodical nature of manual labor. For example, there's a scene in which the crew has to find and resurrect and old Civil War submarine that Bulloch had hidden some time ago. Step one: finding the submarine. Bulloch marked the spot with a log and hid some tools in a tree. Step two: setting up the rigging. Rope, blocks and tackles are attached to two trees and to the chains that lead to the sub. Step three: after the men pull the ropes to bring the sub to surface, Bulloch drains the tanks to establish buoyancy. It would've been simpler, I suppose, to gloss over the entire process in two or three panels. But Towles dwells on the process, and it's quite fascinating as a result.