Marvel Comics creators gathered at New York Comic Con to discuss the topic of diversity through 75 years of Marvel history. Editor Daniel Ketchum moderated Editor-in-Chief Axel Alonso "Ms. Marvel" co-creator and editor Sana Amanat, Kurt Busiek, Kelly Sue DeConnick, writer Kieron Gillen, editor and colorist Marie Javins, editor and "Sabre" writer Don McGregor, and editor and writer Ann Nocenti.

Ketchum started by explaining the theme of the panel: "The World Outside Your Window." "Ever since I started at Marvel, one of the comments that I've heard over and over is that Marvel Comics should reflect the world outside your window, meaning that we aim to capture real-life experiences in the adventures we put on the page, as well as showing that the makeup of our diverse cast of characters -- we want our characters to match the diversity of our audience." Although that has not always been the case in the comics industry, the panelists were eager to discuss the history of diversity at Marvel and suggest ways to make comics more inclusive.

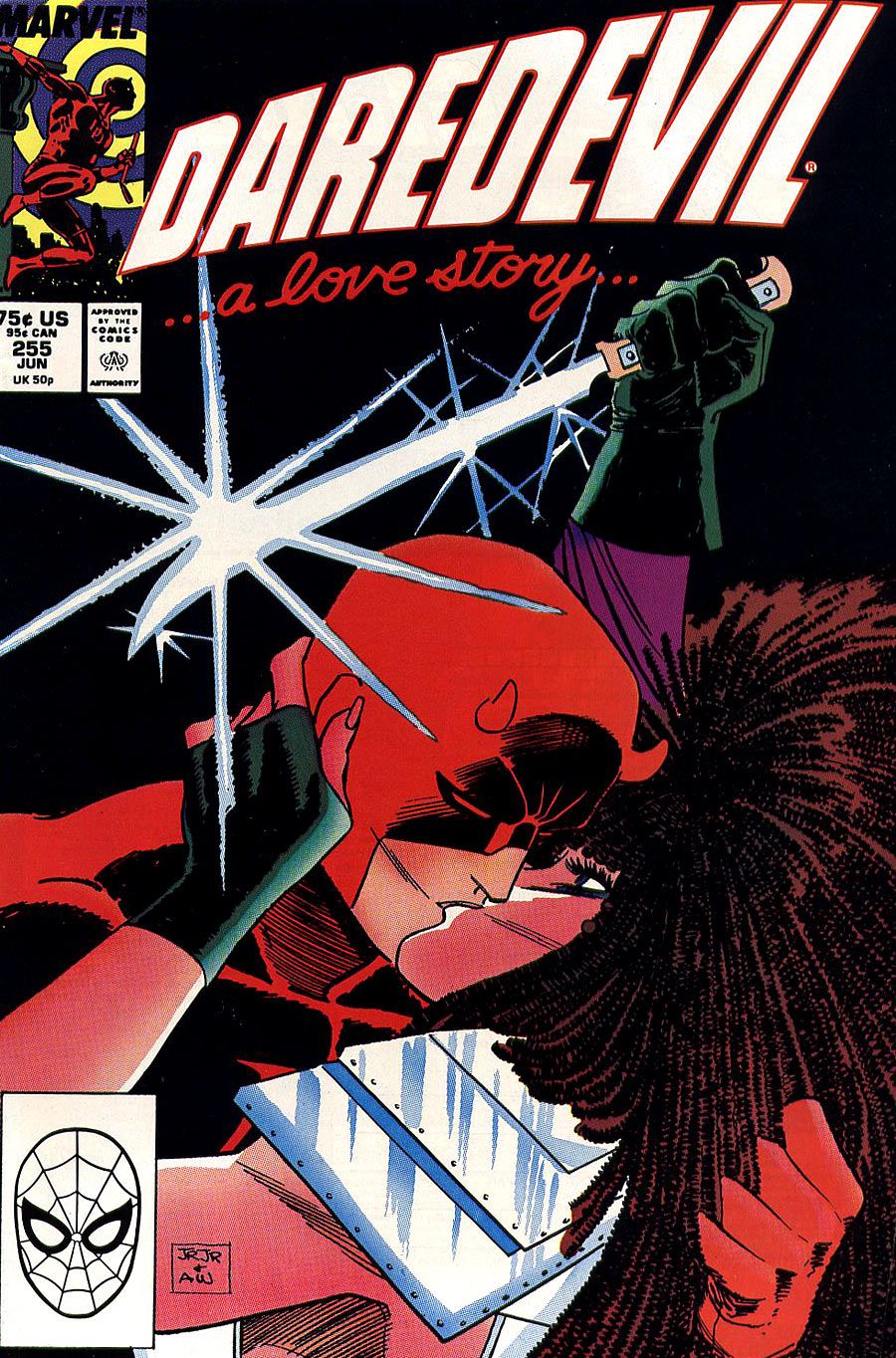

Talking about working with Chris Claremont on "Uncanny X-Men" in the 1980s, Nocenti said, "I remember that gender, color -- it was really all the same to him Diversity just happened very naturally working with Chris." She also talked about creating a new female character in the Marvel Universe. "Typhoid Mary was created because I wanted to explode the idea of gender and have one female who was [both] virginal and kind of a man-killer, literally a man-killer." Introduced in 1988, Mary's split personalities allowed for her to become representative of the depictions of women in comics at the time. "It was a very wide range of females in one female. That was my way of dealing with how, at Marvel, at the time, you had Mrs. Fantastic, who was a really, really good lady, and then you had really evil women. And there wasn't all that much in-between."

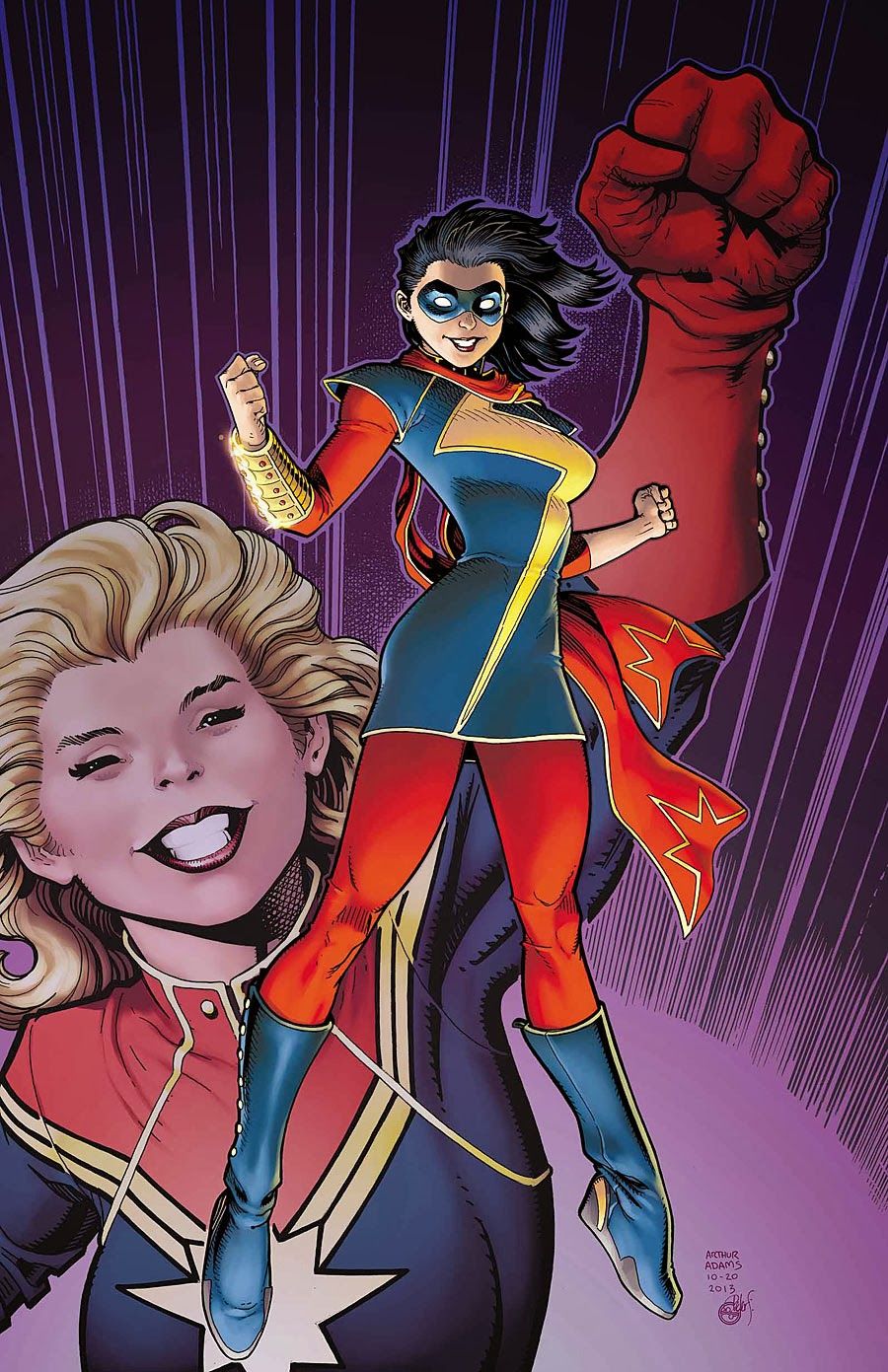

Amanat said that she thought the success of the new "Ms. Marvel" is a good sign that the industry is moving in the right direction on diversity. "There's a Muslim-American superhero that's a woman, and people are actually buying the comic. Twenty years ago, I don't think we thought that was possible."

When he was working at Marvel in the '80s, Busiek related, the world depicted in Marvel's comics did not look much like the world where he lived. "There were a couple stories, almost back-to-back, where a villain came through Washington, D.C. and put a serum in the water that turned everybody into serpent people. And then shortly thereafter, some other villain put a serum in the water that turned everybody in Washington, D.C. into werewolves. I joked to people that the week before that, someone had obviously come through Washington, D.C. and put a serum in the water that turned everybody into white people, because Marvel's Washington, D.C. did not look like Washington, D.C." Busiek said that things have changed, "in a pretty big way," since that time. "If I had to create a new character, kind of the operating rule was, 'This character doesn't need to be a white guy, does he?' Because the Marvel Universe has been overpopulated with white guys since 1939."

Javins explained that some problems with depictions of minority characters were in part due to technical limitations. "You guys probably remember some pretty embarrassing representations of Asians, Native Americans, African Americans. That was because you had only maybe 50 colors that you could choose from. So you probably remember orange people. It's embarrassing looking back at it now, but it wasn't that we didn't know that people are not orange."

"You write what you know, and for me it was just easier to write white females," said Nocenti. "Some of it comes from, how comfortable are you writing something that isn't yourself." As more women and minorities enter the pool of creators, more diversity comes through in their stories. "More voices are being brought into comics, which I think is better than trying to force it and have writers write about something that they don't really know."

McGregor said that he pushed himself to write characters that were unlike himself, sometimes modeling them on his friends. He said that he tried to incorporate homosexual characters and interracial relationships into his stories in the 1970s, but he received pushback from editorial staff. "I think comics is a great medium to tell any kind of story with any kind of character. Any time they told me no, my thought was, why would you want to alienate all these other people who love comics and want to read comics and not include them in the books?"

While in the '70s the censorship was explicit, explained Busiek, in the '80s the rationale was that the books wouldn't sell well. "Look at 'Power Man.' It never sold very well, and that was cancelled, so clearly you can't do another one. Well, what about this series featuring a white guy that got canceled. Does that mean you can't do any more white guys?" DeConnick interjected, "They still make 'Aquaman' comics."

In writing his own books, Busiek made an effort to populate his stories with a diverse cast. About "The Power Company," his 2002 series, he said, "After I had written four issues, somebody pointed out that the only straight white guy in the book was the one character that I didn't create.

"We have not come far enough, and the two things that I think we are not seeing enough of are, we're not seeing enough representation of diverse characters. We're seeing much more than we used to but we're still not seeing enough. And we're not seeing enough participation," Busiek continued. "Diversity doesn't just come from making the characters more diverse; we need a diversity of voices."

"There is a tendency to overlook the editorial staff," said Javins. She pointed out that women often entered the industry later than men, who had trained to become artists from a young age. Women were working in comics, she argued, just not necessarily as writers and inkers. "The bullpen in the 90s was as representative of all cultures in New York as taking a ride on the subway," she said.

"Women have always read comics," DeConnick agreed. "We have this myth that women have recently found comics," she said. "And that is just bullshit." DeConnick blamed target marketing for the dearth of female representation in comics, pointing out that in the 30s and 40s comics magazines for girls were very popular.

"Because women and minorities are lower status, they were actively discouraged from reading books because no one wants to identify down," she explained. "We happily cross-identify with someone who is higher status. But anyone who is higher status is actively discouraged from cross-identifying down because you don't want to do that, you want to aspire. But what this teaches us is a lack of empathy."

DeConnick asserted that this has larger implications than marginalizing female characters and readers. "It teaches women that we are supporting characters in other stories," she said. Though target marketing can be a profitable business strategy, "As an artist, you have a responsibility to push against it." Gillen recalled hearing a complaint from a male reader, who said, "All the good characters are girls, and I can't understand who to identify with."

Busiek shared an anecdote about Dwayne McDuffie, the legendary Marvel writer and editor, recalling how he made "a list of all of the male African American characters in Marvel Comics and breaking it down to what percentage of them were criminals, what percentage of them rode skateboards, and what percentage of them dressed like chickens. I'm not kidding; it was a high percentage."

While the panelists agreed that there is still a ways to go before Marvel's comics truly reflect "The World Outside Your Window," the publisher is on the right track. They encouraged the audience to support diverse comics and diverse creators, and for young creators to write stories that reflect their own experiences.