Grant Morrison and Chris Burnham's "Nameless" #5 is built around a classic horror genre tactic: raising doubt about sanity and perception. In the last issue, Nameless seemed to be the last man standing, the last one to succumb to malevolent alien possession. "Nameless" #5 is a flashback issue that reveals how the main character might not be what he thinks he is.

This is a classic horror moment of truth: the evil the protagonist fears has already made its home inside him without his awareness. This re-framing works to stir up some surprise, but it doesn't max out the potential shock value. This kind of inversion works best when the reader has built up significant trust in one person's version of events, which isn't the case here. Nameless seemed more trustworthy than the other characters, but that's because he was the only character with any dimension; the world-building was always too mind-bending and chaotic for the reader to develop any sense of security.

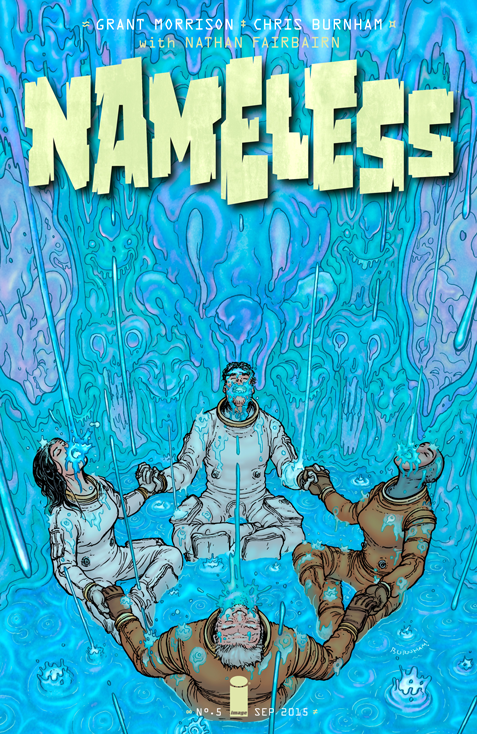

To say that "Nameless" is uneven is an understatement. It's all atmosphere and no solid ground. Morrison intends for the mood to be suffocating and disorienting, and it is. Burnham's page compositions are deliberately fragmented, so that reading "Nameless" #5 feels like a hallucination or a nightmare. The breaks in scenes suggest possible memory gaps or psychotic breaks. His linework has a crazily impressive amount of variation, too. His textures make settings look more imposing or more viscerally disgusting. The alien seance scene shows his ability to make a setting clean and orderly for once, but the other scenes emphasize how his squiggly line easily conjures up associations with infestation, intestines and crawling things.

Fairbairn's dense gray fog outside the Ghost House adds thick heaviness to the air. His red background on the page where the "superbrains" are introduced makes the foreshadowing heavy-handed but clear. The electric neons in the planet scene are surprisingly pretty and enhance the shock of Burnham's abruptly crisp linework.

However, atmosphere and tone can't carry an entire comic. "Nameless" #5 sags under the weight of too many captions and word balloons filled with too much explanation. Morrison injects too much esoteric mysticism into the story and he doesn't have enough plot structure or characterization to hang all these ideas on. He seems to be mixing concepts from Erich von Däniken's "Chariots of the Gods" with infectious psychosis, gore, drug-induced amnesia and justifiable paranoia. However, so far these ideas aren't building towards anything but more of the same fears. In "Nameless" #5, the text in the captions begins to feel like noise. The supporting cast and their names and descriptions feel like wallpaper patterns in the room of an asylum. It's irrelevant and overwhelming at the same time. Once that happens, Morrison loses his ability to keep the reader invested and the story loses much of its initial ability to evoke dread, awe, wonder or disgust.

The fleshy gore and uncanny ambience of "Nameless" #5 still make it distinctive, but the success of the story as a whole is reduced by its lack of lucid moments and connective tissue. Burnham and Fairbairn's art is effective and there are a lot of interesting ingredients in Morrison's vision, but they aren't coming together to become something more powerful.