Regular readers will recall that I teach writing and cartooning classes in local schools as part of an after-school arts program. The last couple of years, I've also taught summer school classes in the subject, and that's been a whole different animal.

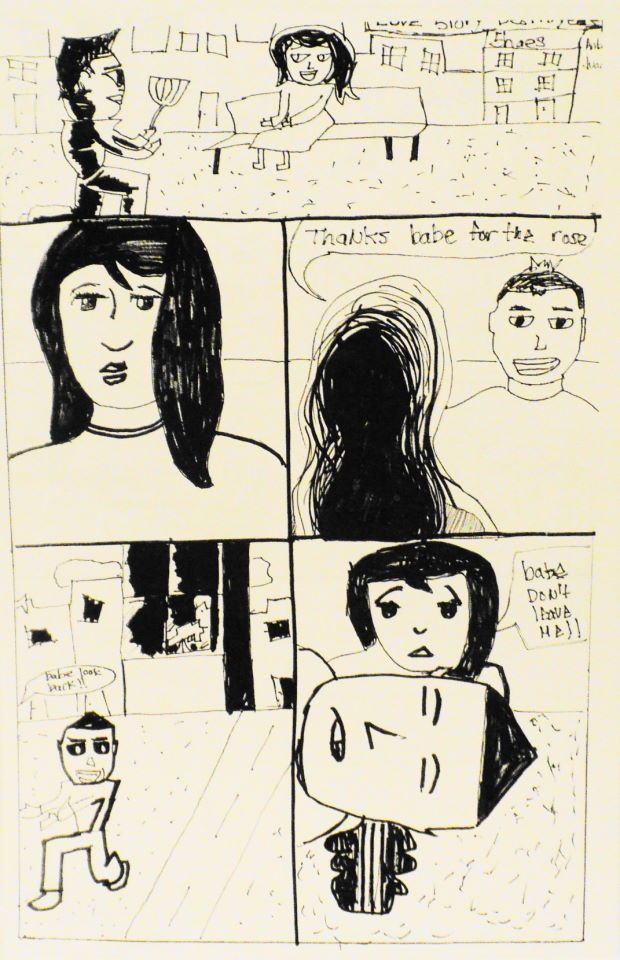

Recently I wrote about the experience for a magazine that was putting together a collection of essays about finding one's true calling. There were severe length restrictions, and I wasn't able to illustrate it with pages my students had actually done, so I ended up cutting it by over half. But I thought you folks might enjoy the original 'director's cut' version, including the pictures. So here it is.

*

I've been teaching writing and cartooning classes for a number of years now as part of our local school district's arts program. Usually for grades six through 12, or thereabouts. It's a lot of fun.

The last couple of summers, though, I've also been doing something more challenging called the "Level 9" program. It's administrated by the YMCA, and what it is, essentially, is a bridge program between middle school and high school-- the program is designed for kids that for whatever academic or personal reason might find high school to be too much for them. Part of it's getting them to brush up on their reading and math skills, and part of it is... well, call it targeted social engineering. Helping kids to be able to fit in better by putting them in a safe place to practice their people skills and coach them a little. The idea is to help them learn to be comfortable as individuals so the prospect of meeting hundreds of new kids doesn't paralyze them with terror.

My Cartooning classes fall under 'enrichment.' That's essentially the reward for showing up for Math and Language Arts in the morning-- the afternoon enrichment classes are things like Cooking and Frisbee Golf and so on... and me, doing my Cartooning 'zine making thing.

Even among the Level 9 group as a whole, who already are a little dysfunctional in the first place, I still tend to get the most introverted and oddball types. The other faculty had a nickname for my class that made me bristle a little when I first heard it: “The Island of Misfit Toys.”

You remember the reference, from Rudolph? The place with all the loser toys no one wants? Yeah, that’s what my colleagues thought of my kids.

The reason it stung is because I used to be a misfit myself back in my own school days. My family was completely screwed up—my parents were drunks who hated each other, and home was a miserable place. Worse, I was good at books and bad at sports, and that guaranteed school was a bad place to be as well. So I retreated into the world of fiction—usually science fiction and comic-book adventure. At first just reading the stuff, then creating my own.

This actually made things worse. It may be hard to believe today when the biggest movies on the planet are superheroes and Star Wars, but when I was a kid, liking that stuff got you jeered at, ostracized, and occasionally even beaten up. Adults were almost as bad. Teachers always said, “Yes, Greg, this comic-book stuff is all very well, but you should do something serious.”

Eventually I got out of high school, though, and what had started as a desperate coping mechanism turned into a joyous hobby, and then paying work. As a colleague of mine likes to say, “You either grow out of it, or you get good enough to turn pro.”

But I never forgot what it felt like, to be desperate and lonely and, especially, so angry all the time. How frustrating it was that no one would listen, that no one cared, that no one ever seemed to get it. And the "Misfit Toys" thing brought all those memories back in a bright sharp surge of anger.

Then something occurred to me. There's nothing actually shameful about that nickname. For me, teaching a comics-making class on Misfit Island is pretty much the perfect gig. I have a job now where I use all those memories, as well as all the junk-culture knowledge gained from those years hiding out from humanity, every day. There’s no course of study to give schoolteachers a background in seventy years of science fiction, pulp, and escapist literature. But I have it, thanks to my own troubled adolescence.

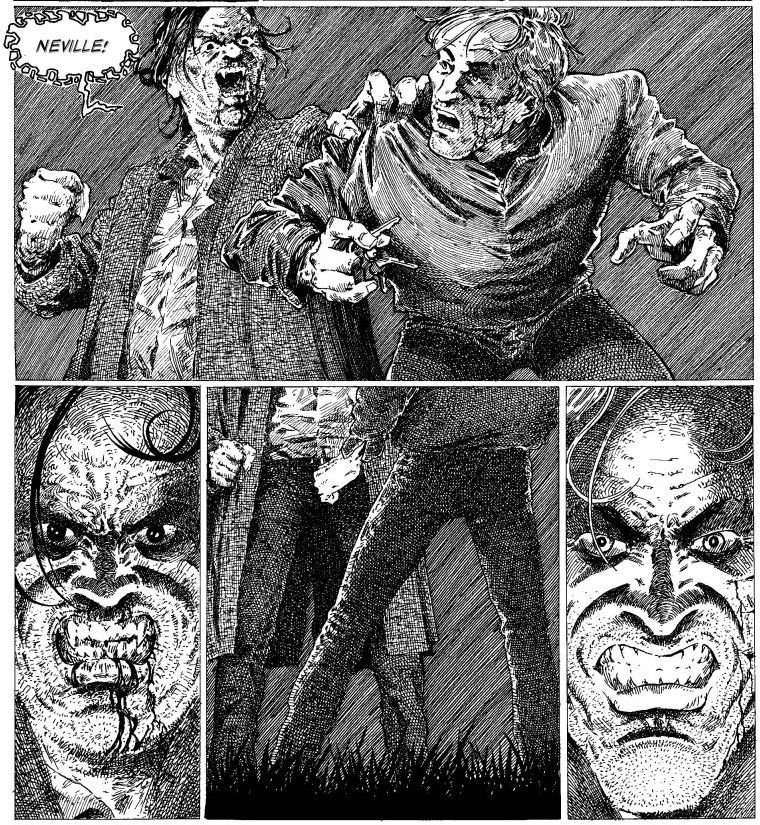

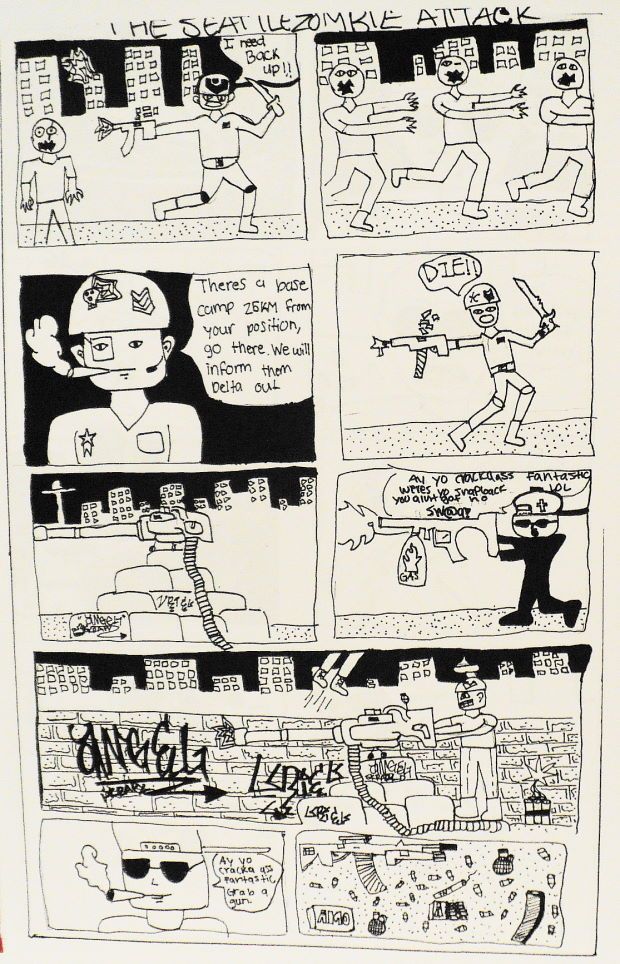

When my kids want to do stories about zombies and post- apocalypse hellscapes, I can talk to them about Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend and how that set the stage for so many that came after.

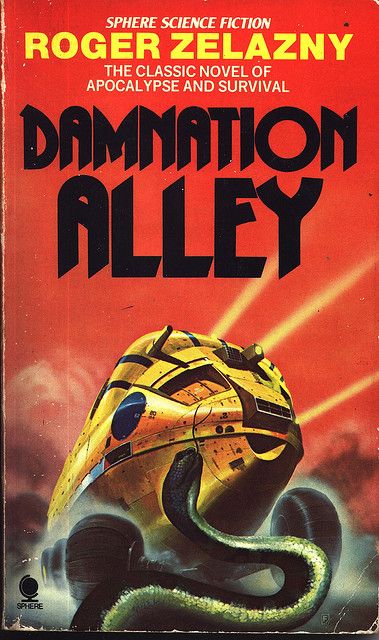

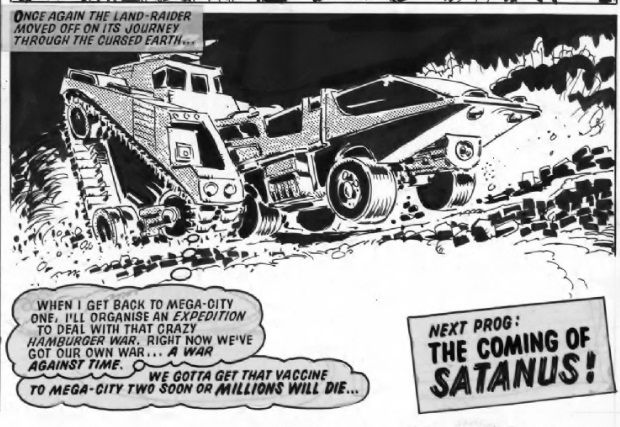

I can tell them about Roger Zelazny’s Damnation Alley, and how that created a bounce reaction in comics with Judge Dredd and "Cursed Earth."

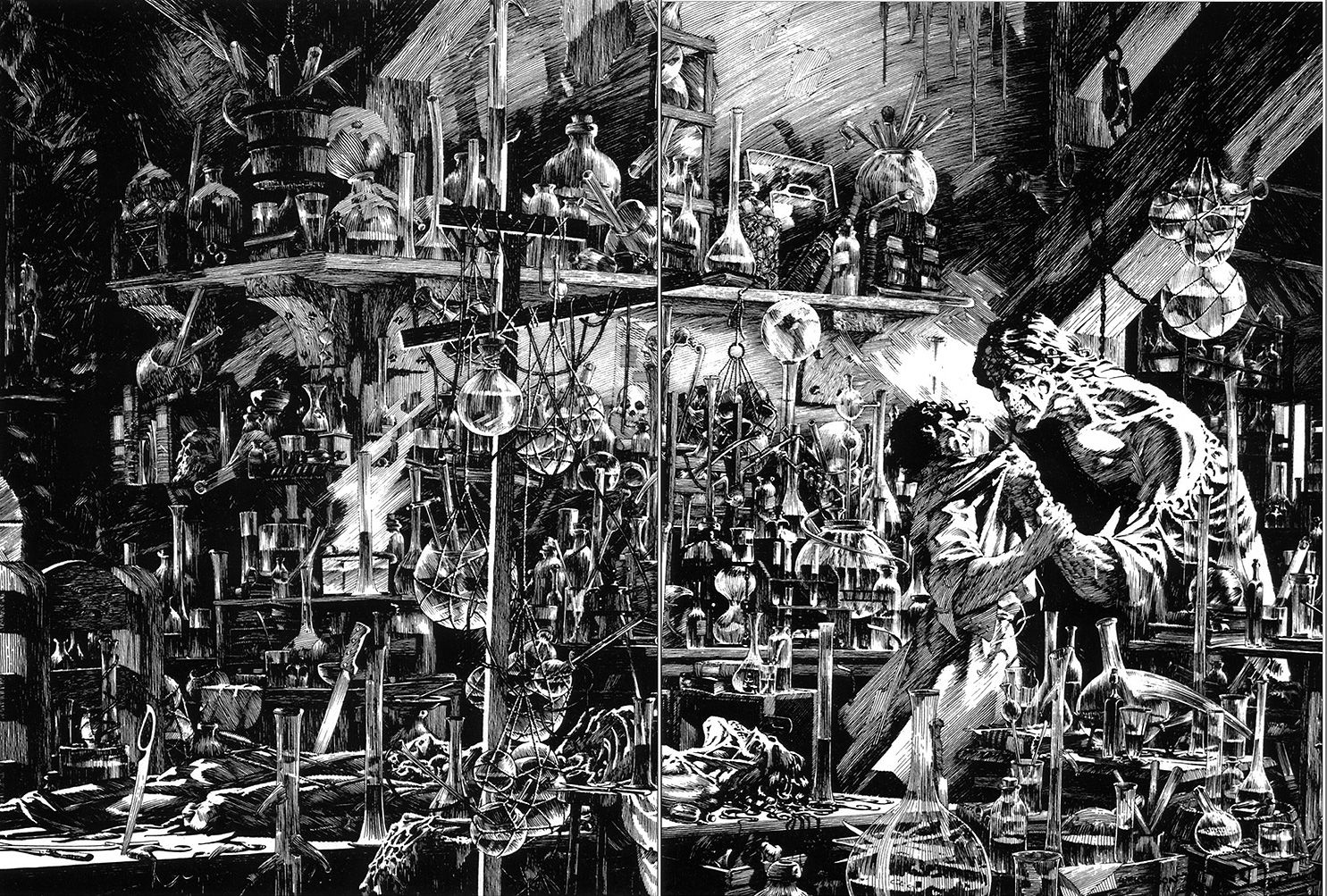

I can show them that there is actually a fine old literary tradition there that reaches back to Mary Shelley and Frankenstein.

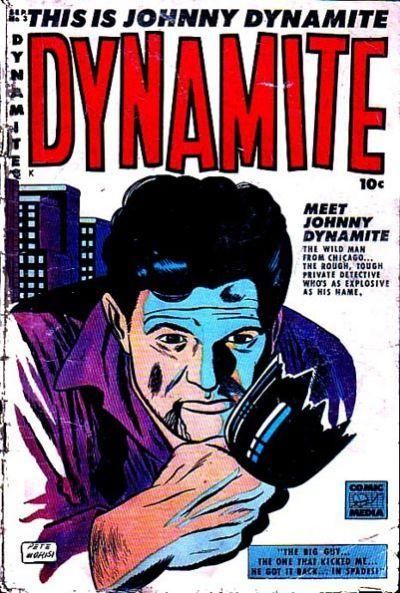

And so on. When the boys wants to write tough shoot-em-ups I can show them some of the great old crime comics by Pete Morisi or the newer stuff from Max Allan Collins, and explain about Hammett and Chandler and talk about the noir tradition and the literary revolution that sprung out of that.

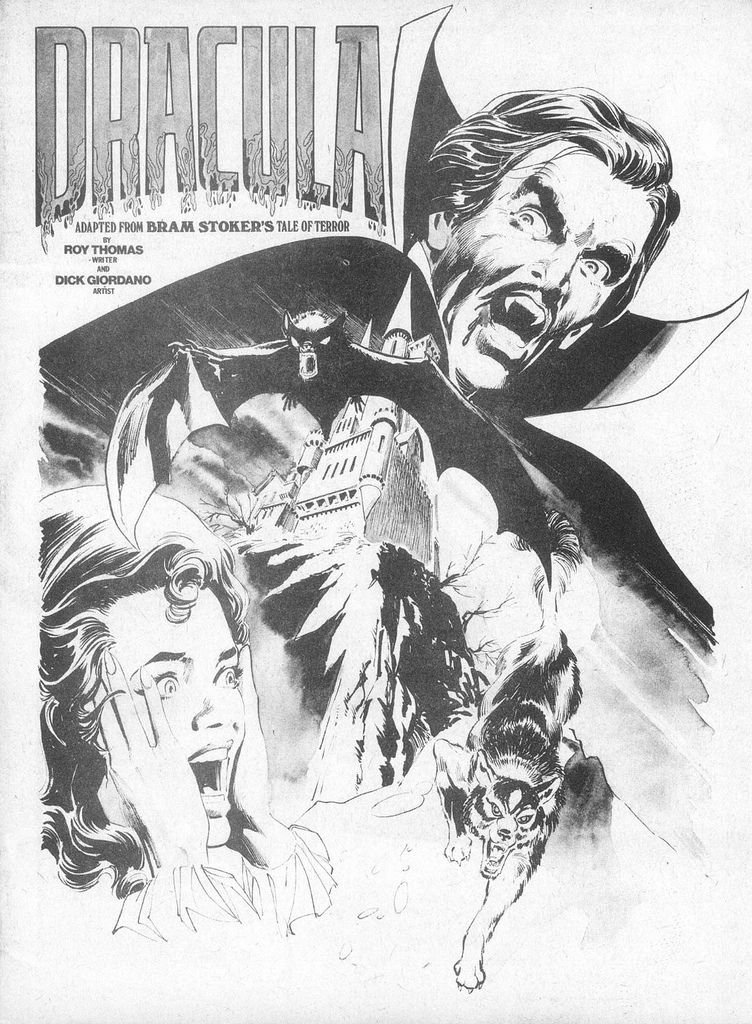

When the girls want to write vampire romance I can talk to them about how that kind of story, when it’s done well, is always a metaphor for the bad choice; whether it’s Dracula or Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

And so on. The one thing I never, ever do is tell them that their ideas are silly or that they should try something more ‘serious.’ Because I remember how that felt, and how it made me instantly stop listening.

Instead, it's about trying to meet them where they are. I had a kid who was very reluctant to try anything. Fernando was completely freaked out over the idea of drawing something people would know was his. I asked him why he'd signed up, if he didn't like drawing cartoony things.

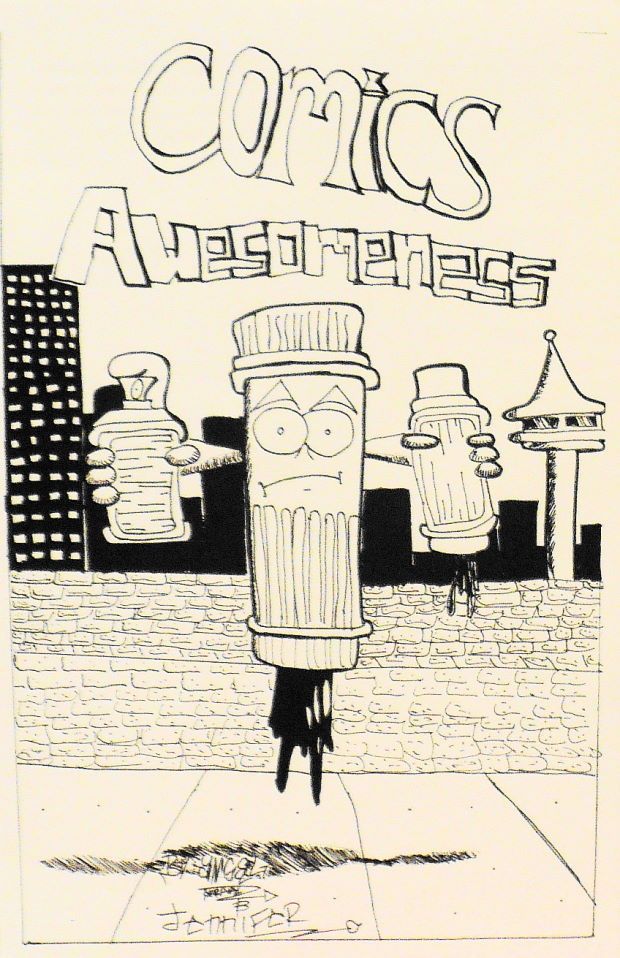

"I like doin' graffiti," he said, sullen, sure he was going to get scolded.

And I had him. I said, "Great, let's figure out something you can do with graffiti art."

It ended up being our cover. It was hard not to feel a slightly smug glow of victory on Showcase Night when he brought his mother and sisters over to our table to show it off, and watching his mother's face as she suddenly looked at her son with new eyes.

There were many, many moments like that-- where instead of just saying "No," I got to say, "All right, let's figure something out," and see a kid pick it up and run with it.

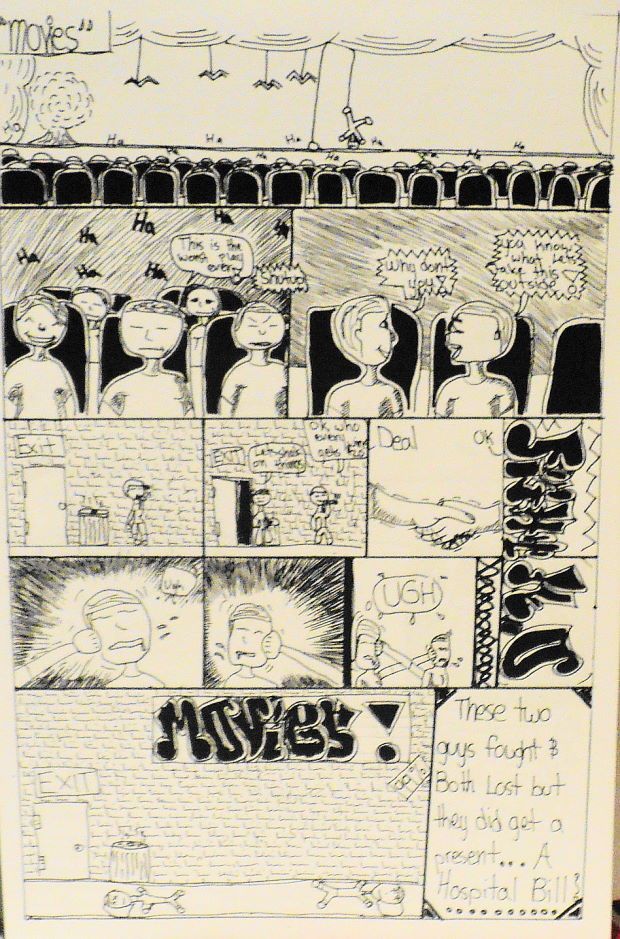

Unfortunately, from the outside it's sometimes hard to explain. The school was in a bad neighborhood down by Rainier Beach, and I had a lot of kids that wanted to do stories about gangs and shooting. Several of my colleagues were a little horrified at what I was letting them draw, but I usually was able to brush them off.

It got to where it was a stock response. "My rule is that there has to be a point, it has to be about something, there have to be consequences. But this is where they live, output is derived from input. I told them if they could meet my standards, and not get us shut down over obscenity or anything, we'd publish whatever they did. I gave them my word. And anyway you're not actually reading what they do. Look again. They aren't glamorizing it. Read the stuff. it's always about how wrong it is, how it hurts people." And off they'd go, somewhat satisfied, but still shaking their heads ruefully over Hatcher's willingness to allow such depictions of mayhem where impressionable children could see them. I occasionally felt like Bill Gaines trying to explain the beheaded woman at the Kefauver hearings.

My favorite part of the school day was usually right at the beginning, when I came to set up my classroom for that day's work. Often the cartooning students would show up while it was still technically their lunch break and start early, rather than staying outdoors with the rest of the Level 9 gang.

I remembered that tactic well-- I used to go hide out in Mrs. Owings' room and she would talk about books with me, back when I was in high school. It was weird-- but fun-- to be on the other end of that, to be the teacher myself.

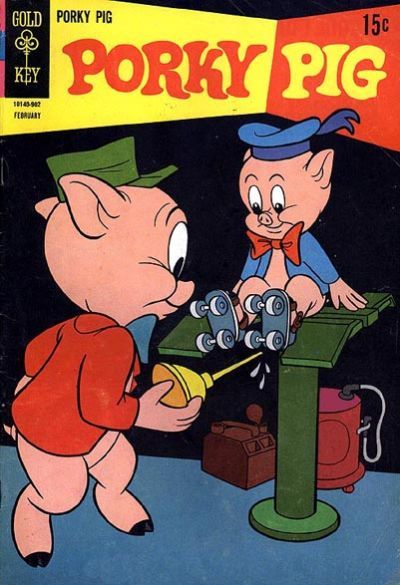

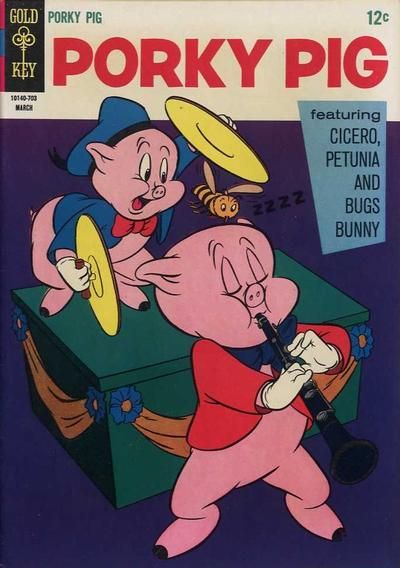

Lisette always wanted to know about comics history. She had several tattered old Gold Key comics she'd scrounged from someone's garage sale and they often perplexed her. She was a huge Looney Tunes fan but she couldn't quite get a handle on why the comics were so different from the animated version. "I don't understand why Cicero Pig isn't in the cartoons."

"Comic book stories have different needs than animation," I told her. "Usually it's about letting your main character have someone to talk to. The Road Runner comics had four little Road Runner nephews that were never in the cartoons. I imagine it was something like that, But let's look him up on the internet and see what we can find."

Lisette was overjoyed to discover Misce-LOONEY-ous even existed. She wallowed in it for lunch period the rest of the quarter, wherever she could find a free computer terminal. Usually it was the one on my desk.

More often than anything else, kids would ask me how I'd gotten to my current position, how did it start, what were my favorites. Haley, especially, would interrogate me about what I liked, how I'd started drawing, what got me interested.

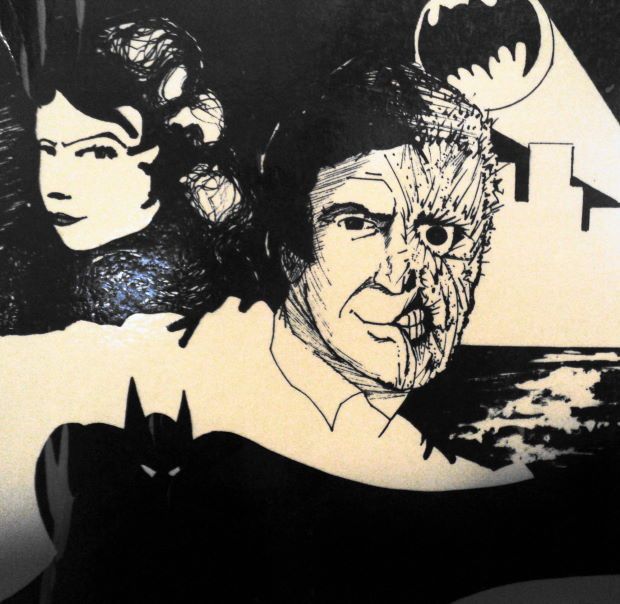

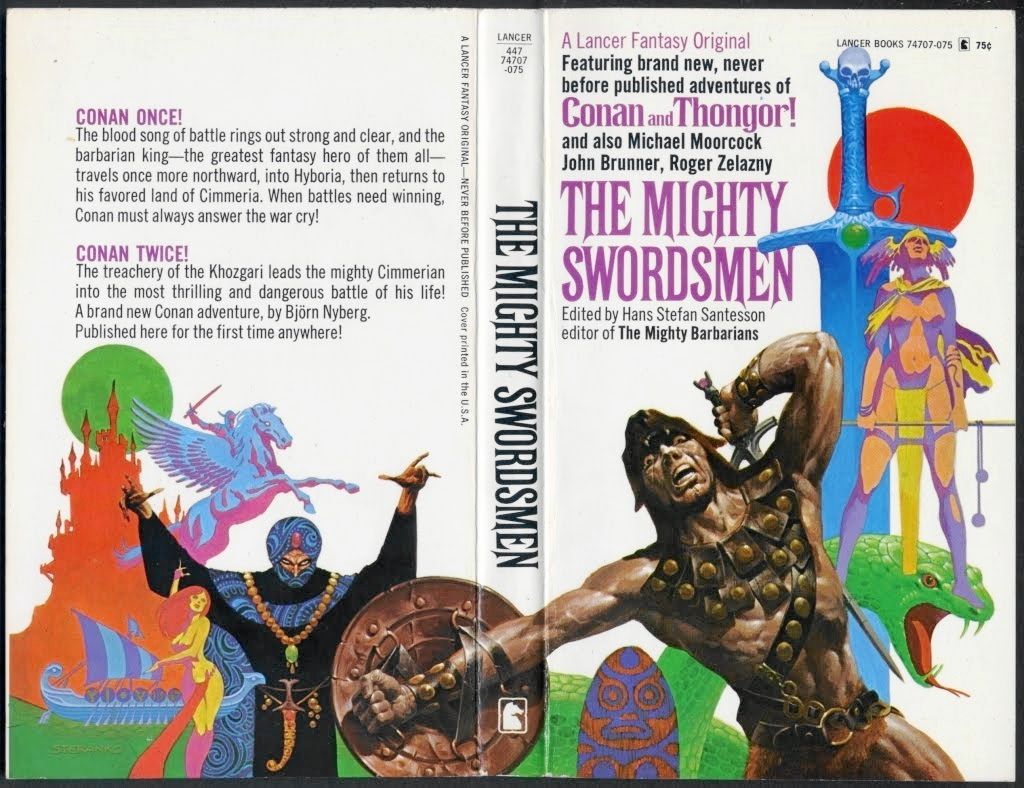

"There was a guy named Jim Steranko," I told her. "He did comics but what I loved were his amazing psychedelic paperback covers. They were really splashy and he worked with a graphics sensibility, the shading was all silhouettes and spot blacks. That was really encouraging to me because it was something I could do, I was mostly using markers and stuff like that. And I loved that collage idea of design, to just jam the images all over each other."

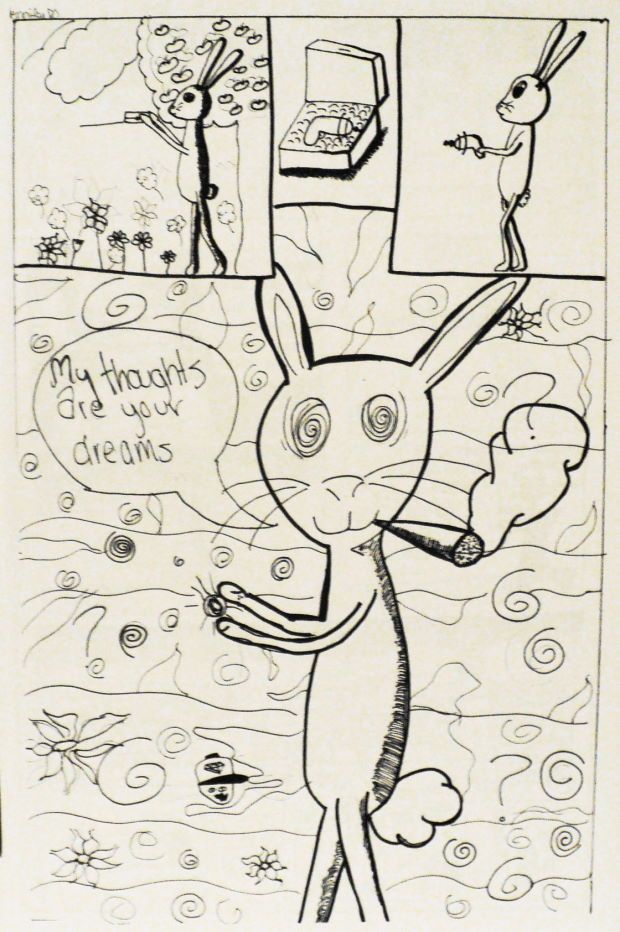

Haley must have enjoyed that, because she ended up doing her own psychedelic collage comic. It horrified some folks but I knew her story was nothing to do with drugs-- the bunny finds an alien ray that transports him into another dream dimension.

What I loved was that it was her trying to do a Steranko thing for me and it was absurdly flattering.

Haley really wanted to see MANHUNTER, as well, after hearing me talk about it, so I brought in my well-thumbed copy of The Special Edition. She loved it so much --after all, Christine St. Clair is a redhead like Haley and a badass-- that I told her she could just keep it instead of sharing in the end-of-quarter grab bag a local comics shop puts together for us of comics and books that the students get as their 'wages' for doing the zines. She lunged at that deal.

After the other teachers saw the books we put out, the jokes and head-shaking were replaced with awe and wonder. “How do you get them to work so hard?” was what I got asked, over and over.

My stock answer was usually, “I let them do zombies.”

But that’s not the real answer.

The real answer is this. Coaching the kids on Misfit Island is the job I’ve been training to do my whole life. Whenever I doubt that there is some sort of plan for the universe, I remember this: I was granted the ability to write and draw, I was forced to learn first-hand what it was like to be a troubled angry adolescent, I hid out in the world of comics and SF until I found a home there... and today I'm in the perfect place to put that lifetime's worth of knowledge to use helping similarly troubled teenagers channel all that angry energy into something constructive. QED.

It was a rough road, getting to my current job on Misfit Island. I hated it while it was happening, a lot of the time. But today... there’s no place I’d rather be.

Fitting in is overrated, believe me.

*

And there you have it. See you next week.