Horror movies, whether classified as "elevated" or made for mass appeal, are time-honored vehicles for social commentary. They often hold a metaphorical mirror up, mining the depths of more real-world traumas to explore as metaphors. As societal fears and unrest evolve, so do the main monsters or tropes. Here is how movie monsters mirrored real-life fears across the decades.

The 1930s Featured Vampires, Mummies and Xenophobia

As the Great Depression took hold, audiences hungered for an escape, from screwball comedies to immersive horror stories. Contrasting American normality against the supernatural allowed an outlet for daily anxiety onto something less close to home and more classically scary: monsters and insidious creatures pulled right from the pages of classic tales. Being scared of something on-screen is a safe way to allow the anxiety, stress and foreboding that already exists inside of an audience to be released, and the Depression was certainly a time when people had plenty of fear bottled up.

At the same time, a more insidious and painfully real monster was also taking hold: xenophobia. The so-called "exotic" villains, mad scientists and vampires with foreign accents, were a manifestation of desperate times fostering an undercurrent of racism. After all, what was scarier than a foreign outsider preying on all-American (white) purity? Other movie monsters, such as mummies and their curses, took colonial guilt and extrapolated it onto the silver screen.

The 1940s Saw Wartime Violence and the Beasts Within

By the time the '40s took hold, Americans and the world at large were trapped in the all-too-real horrors of manmade violence as World War II waged on. All of the horrors of wartime detoured society's underlying fears from "othering" the monsters to exploring something a little more introspective: the monster within. Humanity's own inner propensity for violence, a dormant beast just below the surface, was overtly explored with Lon Chaney Jr.'s iconic Wolf Man, striking a nerve with a world realizing in real-time how easily the violence of men could truly be unleashed.

The 1950s Spotlighted Nuclear Fears and Giant Mutant Dinosaurs

It's not hard to trace the root of the fears in the '50s. From omnipresent Cold War threats to the ongoing guilt of America dropping a nuclear bomb on Japan, the fallout manifested rather literally in mutant creatures and alien invasions, such as the huge, mutant ants in Them!. Godzilla rising from the seas of Japan, freshly radiated into power was a direct result of the true horror of nuclear bombing.

On the homefront, alien invasion movies, from Invasion of the Body Snatchers to The Day the Earth Stood Still to the film adaptation of War of the Worlds, began pumping out, amplifying a double threat of uncertainties. Americans lived in daily fear of foreign threats, namely the Cold War and nuclear annihilation, not to mention the American government's Communism phobia. At the same time, the space program was ramping up, and the unknowns of other planets were becoming more tangible. Who knew who or what the country might find out there beyond the stars?

The 1960s Tackled Civil Rights, General Uncertainty and the Grip of Racism

Societal unrest and tensions ran high as racist values clashed with progressive calls for civil rights in the '60s. Protests and marches took up the call for racial equality, and Hollywood mined racial tensions for stories. Zombies, having roots in historically African voodoo traditions, began their rise to popularity in the 1960s. George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead was a gruesome masterclass in social realism and pointed to the dangers of mob mentality, be it through propaganda or brain-eating zombification. Scenes of police and K9 units aggressively searching for zombies looked purposefully similar to real-life cops tracking down civil rights activists. When Ben, the movie's staunchly human protagonist, is mistaken by the police for a zombie and shot, they coldly shrug it off by saying: ''That's another one for the fire.'' The fact that the movie finished filming merely days before the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was cruelly prescient.

Outside of the civil rights movement, this was a decade of profound uncertainty all around, with generational divides showing more clearly than ever. There were protests on the news, women were gaining autonomy over their lives, gayness was more openly discussed, and the younger generation was rebelling against the Vietnam War. Combine a generation of progressives with a loosening of censorship rules and that decade saw a rapid influx of horror movies that allowed audiences either an outlet to process all the change or worked as cautionary tales against betraying traditionalism.

Movies such as The Haunting took a skeptical and scientific eye to typical ghost stories while weirder, more surreal horror such as Carnival of Souls more overtly explored the nightmares of one's own mind. By the end of the decade, movies like Rosemary's Baby, for example, tackled women's bodily autonomy and the reticence of the old guard and religious fanaticism to allow female empowerment.

The 1970s Revealed More Material Fears - Slashers and Serial Killers

Moving into the '70s, fears became more based within the mortal realm. As the era of serial killers began, unspoken fears naturally centered on being the next unwitting victim of a homicidal maniac. Combine that with the general feeling that, after a decade of so much turmoil, the suburbs were no longer the idealized safe harbor of the American dream sold to nuclear families and the slasher genre was ripe for stardom. Female empowerment was again the base for cautionary tales, too, as the "have sex, get killed" stereotype took root. Demonic possessions and hauntings such as The Exorcist coincided with the uncertainty of societal upheaval, a pattern that would also repeat in the 2010s with a booming interest in The Conjuring films.

The 1980s Focused on Themes Surrounding Automation, Corporations and Aliens

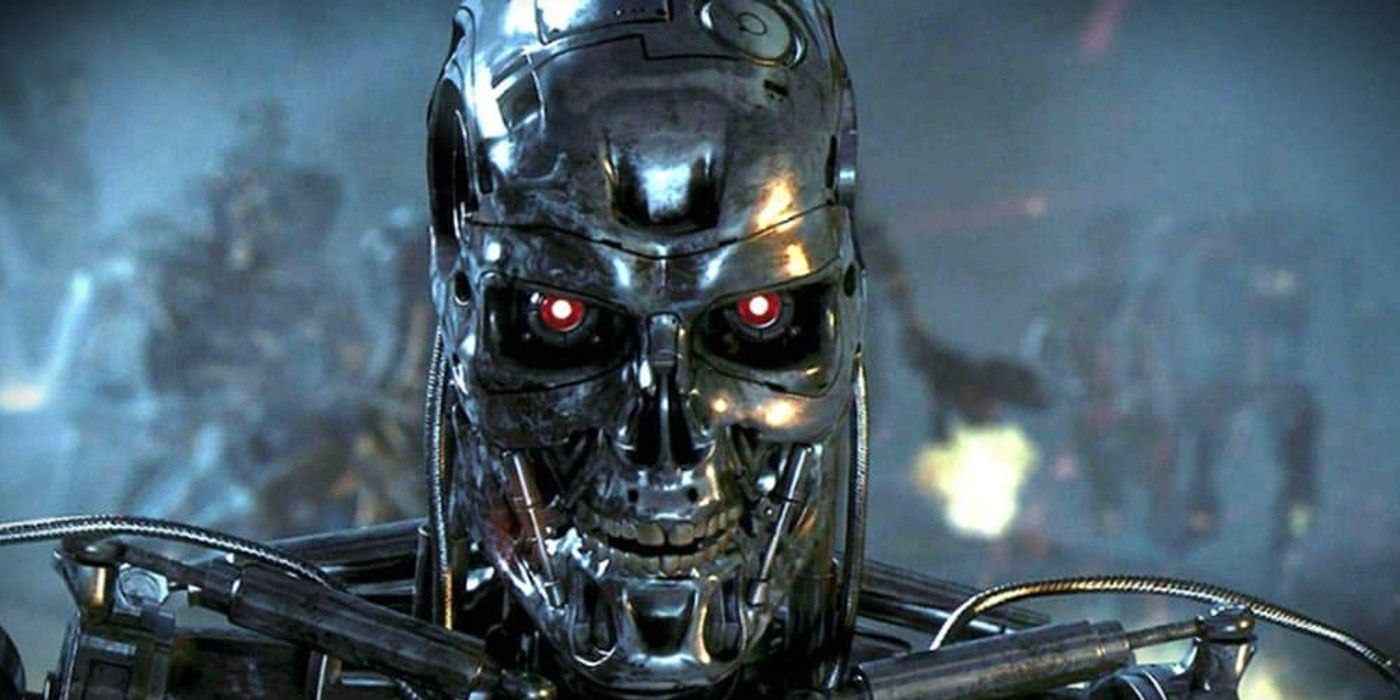

Reagan-era America ushered in a whole new level of subconscious uneasiness. Increases in automation created fears of obsolescence, while the trickle-down corporation heaven of the '80s created a looming threat of total Big Business control. AI villains such as in The Terminator spoke to universal fears of technology outpacing people, while blockbusters such as Ridley Scott's Alien (released in 1979 and spawning a franchise into the 1980s) took the corporate overlords threat (the Company, a faceless corporate monolith at peace with sacrificing people in the name of quarterly goals) and magnified it into the vacuum of space.

The 1990s Waved In Riot Grrrl Feminism and Witchcraft

Grunge and new-wave feminism took hold in the 1990s, with everything from Daria's hyperintelligent yet cynical takes to the punk feminism subculture of Riot Grrrl. From left to right, girl power separated greatly from any male dependencies was coming in waves, and a patriarchal establishment was unsettled by women coming into full power. So naturally, witchcraft and witchy movies took over. While movies such as The Craft, The Blair Witch Project and The Crucible were cautionary tales meant to show the terrifying effects of female power (in the form of conjuring here) gone too far, other witch-starring movies like Practical Magic boldly spliced scares with emotional messages about the loving power found in sisterhood, female independence from men and traditionally sidelined domestic roles.

The 2000s Double Downed on Found Footage and Ultraviolence

The 2000s were all but fully defined in America by the attacks of September 11th. That was a sobering loss of innocence for an entire nation, swiftly switching gears all around from the optimism and progression of the 1990s to a reactionary and anxious track. Horror movies reflected that change, too, shifting suddenly from the magical and the mystical to gruesome, hardened horror that could theoretically be played out at any time in real life.

In a post-9/11 world, people quickly became hardened, extremist and pessimistic as everything was heightened. Gory and violent "torture porn" films such as Saw or Hostel found great success as did found footage films. Watched by an audience so far removed from the event and helpless to do or know anything other than that a brutal, unhappy ending was in store, found footage reflected feelings of disconnect and alienation and the fear that we were ultimately doomed and alone, far removed from help, hope or the risk of emotional involvement. Extreme violence and found footage observations summed up an entire generation of the overwhelmed and disconnected.

The 2010s Hammered Home the Monster Is Us Theme

As audiences and storytellers moved into the 2010s, people's biggest fears took another inward turn. The calls were coming from inside the house -- the personified house. Were the real monsters humanity all along? Social commentary horror hit its greatest highs since Rod Serling's Twilight Zone stories of the 1960s with auteurs like Jordan Peele carrying the torch into the pit of man's fears. Get Out became an instant classic by tapping into more personal and cerebral fears, namely the sinister effects of sugar-coated, sly racism. And if the monsters weren't our darker, crueler human selves, they were the grief we carried with us, such as in The Babadook.

The 2010s/2020s Transitioned to the Idea That the Monster Is Trauma

As we continue on through the later 2010s through the early 2020s of today, horror continues to creep inside of us. There is a new influx of ghost stories in tumultuous times, found in Mike Flanagan's The Haunting anthologies or the sins of generations coming to a head in the Fear Street trilogy, representing collective fears of personal and generational pasts literally coming back to haunt. A Lynchian sense of dread pervades the landscape, rich with feelings of being trapped in a life people never envisioned for themselves, like the eerie claustrophobia of Vivarium.