SPOILER WARNING: This article includes extensive spoilers for Tom King and Mitch Gerads' Mister Miracle #1, on sale now.

CONTENT WARNING: This article includes discussion and images of suicide.

Can the world's greatest escape artist truly escape death? As DC Comics celebrates the 100th anniversary of Jack Kirby's birth with a raft of new series and specials featuring his creations, the most anticipated and most ambitious has to be the twelve-issue Mister Miracle series by the Sheriff of Babylon team of Tom King and Mitch Gerads.

RELATED: Batman: Tom King Explains the Strange Importance of Kite Man

Whatever fans might have anticipated from the reunion of King, regarded as one of comics' top new talents thanks to his work on The Vision, Batman, and Omega Men, and Gerads, who is also acclaimed for his work on The Punisher, Mister Miracle is almost certain to defy expectations. The first issue breaks the chains of the conventional superhero narrative, while at the same time being deeply immersed in the world of the fantastic. It crashes brightness up against the dark, to incredibly unsettling effect, and presents a world where everything -- everything -- can be turned inside out at moment's notice, evoking the same sort of terror as David Lynch's Mulholland Drive or Inland Empire.

Darkseid Is

The issue opens with Scott Free lying on his bathroom floor, in costume, bleeding out from gashes on his wrists in an apparent suicide attempt. It's a shocking image, but it's not merely shocking; the ways in which Scott's attempt is discussed -- and not discussed -- throughout the issue reveals much not only about Mister Miracle, but also those around him, from his wife Barda to his divine father and brother. There's also significant reason to doubt whether Scott's attempt was truly unsuccessful, or whether his greatest escape may still be in progress.

Because nearly every detail that follows calls into question the stability of Mister Miracle's objective experience.

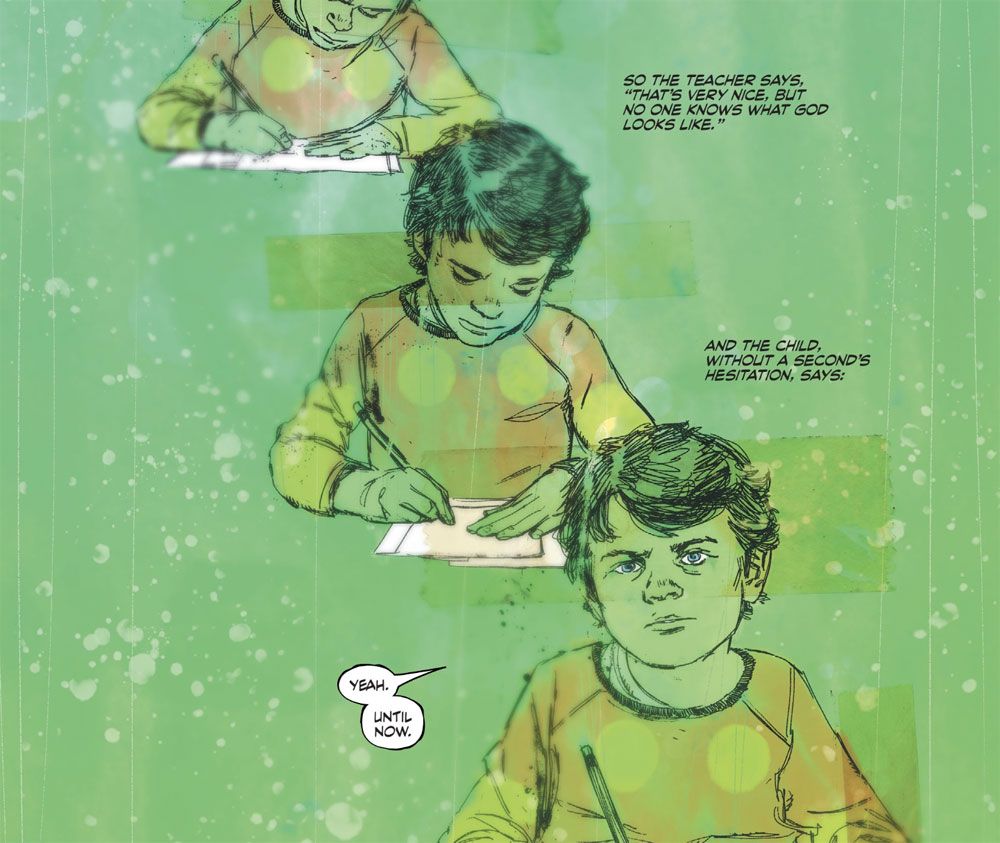

After the suicide attempt comes a page from Gerads that appears simple at first glance, but packs in a ton of nuance. Instead of panels, a sequence of images of a child drawing, alongside a strange sort of joke told in unboxed captions. The child is shown only from desk level up, an isolated figure in repeat. He is recognizable as Scott Free, thanks to his mop of black hair and the hint of the Mister Miracle costume seemingly caused by distortion to the image itself. The background is, or appears to be, a photograph of water, fading to green through age and exposure to sun; each instance of the child has a yellowed piece of tape over his face, not obscuring his image but clearly visible nonetheless.

The child tells his teacher that he's drawn God, to which the teacher replies, no one knows what God looks like. The punchline is, "Yeah, until now."

This joke is repeated later in the issue by Scott's friend Oberon, though Barda soon after reminds her husband he has recently died of cancer.

In between, Orion (the son of Darkseid, raised on New Genesis) Boom Tubes his way into Scott and Barda's apartment to "teach" Scott (son of Highfather, raised on Apokalips) the error of his ways through a solid beating. After Barda puts him in his place -- "Only Granny can teach" -- Orion departs, but Scott is in for an even bigger blow.

It's nightmare-logic. The world is not what you thought it was, and that is a source of indescribable terror.

Oh, and then another stomach-dropping scene. (This issue is relentless.)

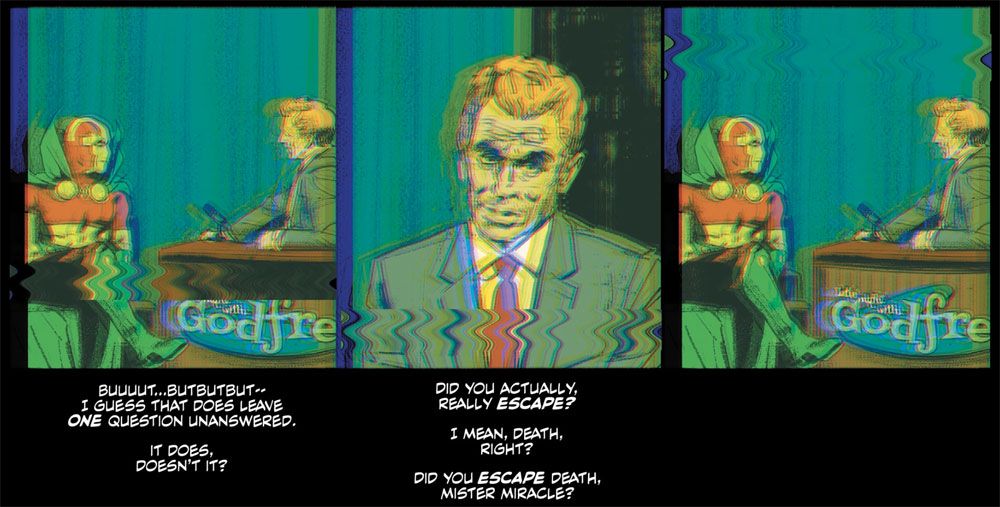

In a sequence heavily warped by stylized TV static and distortion, Mister Miracle performs a gruesome escape on a late night television show before conducting an interview with the host, whose name we see is Godfrey. Kirby fans will certainly recognize this as the Apokaliptian propagandist Glorious Godfrey, though Scott does not appear to make this connection. The escape artist tells Godfrey, in halting tones, that his suicide attempt was "a trick," his search for a greater challenge leading him to consider "what can't I escape from? What shouldn't I escape from?"

"Death. No one escapes from death."

"So I killed myself."

Mister Miracle mimes cutting his throat. The audience roars with laughter. The distortion intensifies.

full

And then Godfrey looks straight at the camera.

The pacing for the rest of the Late Night sequence -- another four panels on a nine-panel grid, in which almost nothing happens -- is remarkably unnerving.

Things accelerate quickly. A scene between Mister Miracle and Highfather, the supreme god of New Genesis, follows, in which we learn that Darkseid has attained the anti-life equation and that Scott does not have a great relationship with his dad. Then the scene with Oberon, and then Orion calls Scott and Barda home to New Genesis, telling him there's a war on and Highfather is dead.

Before they step through the Boom Tube, though, Mister Miracle again confesses that something isn't right. "Everything's wrong … I don't know how to escape this." Barda, in a repeat of Orion's actions earlier, attempts to snap her husband out of his existential dread by knocking him to the floor. For the moment, it will serve. Together they step into the Boom Tube.

Darkseid Is

In addition to the strange episode of the child and his drawing, there are number of intriguing formal elements to this issue. King is, of course, known as a fan of the nine-panel grid made famous by Dave Gibbons' Watchmen work. He and the artists he works with have used it to incredible effect in Omega Men, Sheriff of Baghdad and even Batman. Most of Mister Miracle #1 is on the modified grid, the child page being the most memorable exception, and within this device, there are a few very interesting things going on. The Godfrey sequence contains a conspicuous amount of black ink, as images within the nine panels are reduced further inside to allow for dialogue to run, caption-like, underneath, white on black. Also, as distortion increases, the panels nearly bleed into each other, a blue haze emanating from the "television" and corrupting our view. The black space grows even greater for the punctuating "Darkseid is" panels.

Backing up...

Beginning just after Scott arrives at the hospital on page 3, nearly every page contains an all-black panel containing only the phrase "Darkseid is." (The exceptions are the scene with Highfather, and the final two pages as Mister Miracle and Barda prepare to depart for New Genesis -- does the combined light of these New Gods drive out Anti-Life?) The phrase has seen a good deal of use in Darkseid stories, especially when the god of evil stands triumphant -- Final Crisis, another epic that saw Darkseid bend the universe to his will using the Anti-Life equation, also featured the phrase prominently. In a cosmos devoid of hope, devoid of choice, Darkseid encompasses all of existence. Darkseid is.

The first instance this issue comes after the ambulance and before Scott awakens in hospital -- in other words, if he is in the realm of the dead, this is the very panel he enters it. The panel repeats just before Orion's arrival, and before his "lesson," and before his reprieve. It's astonishingly effective punctuation. It drops in a moment of calm between Scott and his wife, before he realizes her eyes are the wrong color.

But in the Oberon scene, things deteriorate. Now there are two black panels per page, and they seem to come in the midst of mundane activity. And when Barda tells him the truth, now there are four, every other panel, like a checkerboard. The checkerboard reverses on the following page; now five of nine panels are black. Punctuating every moment, every thought. For all of Scott's protestations that his suicide was one more escape act, this reads a lot like depression -- there are a number of ways this could play out, subtly or overtly, over the course of a twelve-issue series, and King and Gerads are strong enough storytellers to pull it off with care.

Then an all-black page. Darkseid is.

Darkseid Is

One more: the issue begins and ends with a carnival barker-style narrator, imploring readers to roll right up for the adventures of Mister Miracle; this narrator is absent through the rest of the issue. King used a similar device in The Vision, setting the scene through a tranquil "voiceover," and here it almost feels like a TV intro and "cliffhanger" spiel. You can imagine the voice, easily. Given the performative aspect of Mister Miracle, though -- we see posters of his death-defying escapes, modeled after actual comic covers, and of course there's the matter of Godfrey -- one can't help but wonder if the narrator is in on the game, whether he or she has some more tangible role to play.

Mister Miracle #1 is a superhero comic with very little action, and yet so much happens. The threat is greater than any giant monster; greater, even, than Darkseid. King and Gerads once again stun with an original and unexpected story, powerfully told. Fans of Kirby's character may on the one hand be dismayed to see their hero put through so grim an ordeal, but there's nothing out of place here in terms of the Mister Miracle concept or Scott and Barda as they have been previously established; this series is a far cry from Justice League International, for instance, but these are recognizably the same characters, their love is strong is precisely the way we've seen time and again. Readers coming to these heroes for the first time should be able to empathize immediately with Scott and Barda, and can easily take the assorted Fourth World conflicts in stride; the relationships are clear, the rest can fill in later.

This issue is an extraordinarily heavy read, but one that is also extraordinarily rewarding.