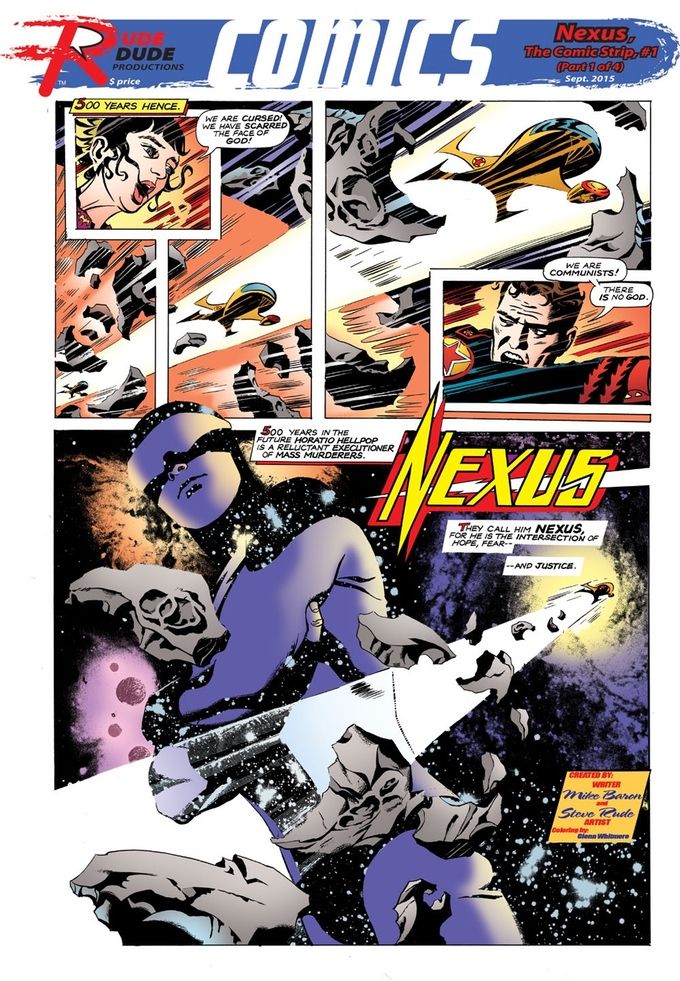

In the 1980s, Mike Baron flipped the superhero genre on its head with Nexus, a comic about a reluctant executioner of mass murderers. Meanwhile, on television, a bunch of surprisingly dark characters were running missions in a futuristic helicopter on Airwolf. Now, 30 years later, Baron has written a story for the upcoming Airwolf graphic novel, which will be released in August by Lion Forge.

Baron came up with an interesting twist for the Airwolf comic, pitting the high-tech chopper against some very low-tech World War II-era planes. He's also still writing new Nexus comics, and artist Steve Rude is running a Kickstarter campaign to publish the newest story online and in print.

Baron spoke with ROBOT 6 about Airwolf, Nexus and his other projects, and he threw in some advice about writing comics as well.

ROBOT 6: Were you a fan of Airwolf when it was first running, or was this job your introduction to it?

Mike Baron: It was the latter, actually. I was aware of Airwolf because I kind of followed the career of the actor Jan-Michael Vincent. [Lion Forge editor] Shannon [Denton] asked if I would be interested in writing Airwolf, and I said “Sure, I’d love to!” The first thing I did was look at the Airwolf comics they produced before. The comics, while based on the TV show, are kind of sui generis. They recreate the scene with fresh characters.

What sort of parameters were you given for the story, in terms of characters and continuity?

When I read the previous Airwolf material, I grasped the concept right away, and the marketing and age group at which it is aimed. It’s light PG-13 — you can allude to heinous acts but you can’t show them on the panel. I love the milieu. It’s the milieu we grew up in — The Man from U.N.C.L.E, James Bond, I Spy — coupled with the latest in technology, which is kind of a sub-theme of shows in the '80s. If you think of The A-Team and Knight Rider, they are tough guys with technology. That’s what Airwolf is, only in this case it’s a superhero copter.

In your story, the villain uses World War II vintage weapons and aircraft against the high-tech Airwolf. Was that your idea?

Yes. I have been thinking about that for a while, how dependent we have become on technology, that if something were to happen to the technology and it were all to go away, and we were deprived of our computerized weapons, we would be a sitting duck for the old technology. Everybody thinks every country is working on a giant EMP [electromagnetic pulse] weapon, a low-altitude nuclear detonation which would wipe clean all the computers and render them useless. If it happened when planes are in the air, it would be big trouble. It’s not that this low-rent general [in the comic] had an EMP, it’s that he was working with what he had, and he was also smart enough to recognize that modern technology doesn’t allow for old technology, so he could use his weapons to take down Airwolf.

This comic has a lot of action scenes. Do you have a particular technique for writing that sort of material?

First I write the outline of the story, so that everybody who reads it can understand the story arc and the characters and their motivations. You have to have the personalities of the characters first. That will affect their action style and fighting style. When I get to an action sequence, I sometimes will draw it out by hand for the benefit of the artist because I think it is important for the reader to see the action unfold in a clear and realistic manner. I have always tried in my comics to show the action unfolding in a clear and logical manner. And when it comes to hand-to-hand combat, that means you hold the camera steady and let your figures move, and avoid extreme closeups. You have to show both combatants in an establishing shot. A good action series is a whole series of establishing shots, showing the whole scene and the action as it unfolds. For instance, if someone is showing a roundhouse kick, you have to take into account the stance of the two combatants, where that leg is, and where the kick is going to go. In the same way, when you are doing aerial combat, you can’t just show a close-up of a jet firing a rocket and a plane blowing up, you have to have an establishing shot so you can see both combatants in the same frame and their physical relationship to each other.

You have been writing comics since the 1980s. How have the themes in your stories changed over time?

I feel that it is still me learning about writing all the time. Although I’m still in a place where I’m happy with a lot of the stories expressed in Nexus in the '80s, I have changed, and I hope the stories reflect that. I always tried to portray Nexus as a thoughtful and moral man — not Lobo! The basic contradiction is he’s a good guy who is forced to go out and kill, but since he’s also a man who understands there is such a thing as evil in the world, he is able to do it. He is able to carry out those executions because he believes it is the right thing to do, with almost no exceptions. That hasn’t changed at all.

We are trying to be less overtly political. A lot of those early Nexuses were obvious riffs on situations that were occurring in the world. We are still dealing with that. The people who read the comics are not aliens. We are all human beings, so for the story to make sense, it has to make sense in human terms. All the problems that are with humanity since we crawled out of the cave are still with us; technology progresses but the basic human being is still the same. Nexus still has inner doubts, self questioning, bouts of anger, but he is doing the best he can.

How did you learn to write comics?

I always wanted to do comics, and I started out by writing my own comics and trying to illustrate them. I was a half-assed illustrator, but I think that’s how people learn. I always had an instinctive understanding of the form and just knew how to write it. I never had any natural skill with anything in my life except writing comics. It was just this conviction, and I guess I was pretty close on the target when we started in. My understanding of comics has evolved over the years. It hasn’t changed drastically, but it has helped me understand the form much better. I have certain principles that I follow, and the first, the most important, is to “Show, don’t tell.” We have all seen that panel where an apple falls from the tree and hits a guy on the head, and the caption says “An apple falls from the tree,” and the guy says “An apple!” There’s always that urge to add words to the panel; you say, “I’m a writer. I’ll add words!” But that’s not the case. Show, don’t tell.

The action flows from left to right, it should unfold in a clear and logical manner, the readers should be able to see the action unfolding, so you hold your camera steady and let the participants move.

Denny O’Neil said you should never have more than 36 words in a panel. There’s a good point to that. You don’t want to overload a page with text. It becomes a bit confusing and off-putting — unless that’s the point, but readers who are used to going through a comic at a certain pace are going to get frustrated. A writer can control the pace at which a reader goes through the comic. The writer sets the pace by the number of panels, varying the size of the panels — there’s a rhythm. I learned this by reading Uncle Scrooge comics by Carl Barks. He was a master of setting the pace.

What else are you working on?

I will be adapting my novel Biker for ComicMix. Chris Cross is the artist. It’s the first in a series. I have completed two more Josh Pratt novels, nothing supernatural, very tough, crime-oriented stories about Josh Pratt, a reformed motorcycle hoodlum who gets out of prison and becomes a private directive. Pretty grim, but pretty cool too.

And a new Badger comic?

Badger will be five connected stories, but they cover so much, it will be a world tour. The first issue is grim. There’s nothing there that would send you running to the cops, but when you tell the story of multiple personalities, they never arise out of happy situations, and most multiple personalities arise out of childhood abuse. I’m just trying to show the pressures that form the Badger. It’s a new origin story.

It's five issues — I wrote them a while ago, they were done, although we are continuing to tinker right up to the end.

What about Ginger Fox? I was reading your interview with Chris Arrant from a couple of years ago and you mentioned you had a new script.

Yes! It’s a sizzling script. All I need now is a publisher. I suppose we could throw it together and find someone to take a flyer on it. It’s a really good script. I was bummed about Ginger; I felt I could do a better job. The new script absolutely sizzles. I would love to see it in print, but right now I can’t even think of anybody [to publish it]. We could go online, but that would require an artist to put in his sweat equity.

Are you more comfortable with long-form or short-form works?

I enjoy them both. Writing a novel compared to a comic is like skiing down Mount Everest as compared to water skiing. In both cases I do a detailed outline. I carry a notepad with me and I jot down ideas constantly. When I get enought ideas together to do an outline, I can see the overall arc of the story, where the beats are going to be, and the outline has to be highly readable. If you give it to someone who has no interest, they have to say "Hey, I want to see the finished story!" or else the outline has failed.