“Max will know what to do.”

That’s what Mickey Spillane, creator of Mike Hammer, said to his wife before his death in 2006. “Max” is Max Allan Collins, who befriended Spillane and, as his literary executor, has completed over a dozen posthumous Mike Hammer novels.

Like Spillane, Collins is a prolific writer who knows his way around both comics and novels; Spillane started out as a comics writer and originally created Mike Hammer as a comics character, while Collins is the author of Road to Perdition, Ms. Tree and several shelves-worth of mystery novels (some written with his wife, Barb, under the name Barbara Allen).

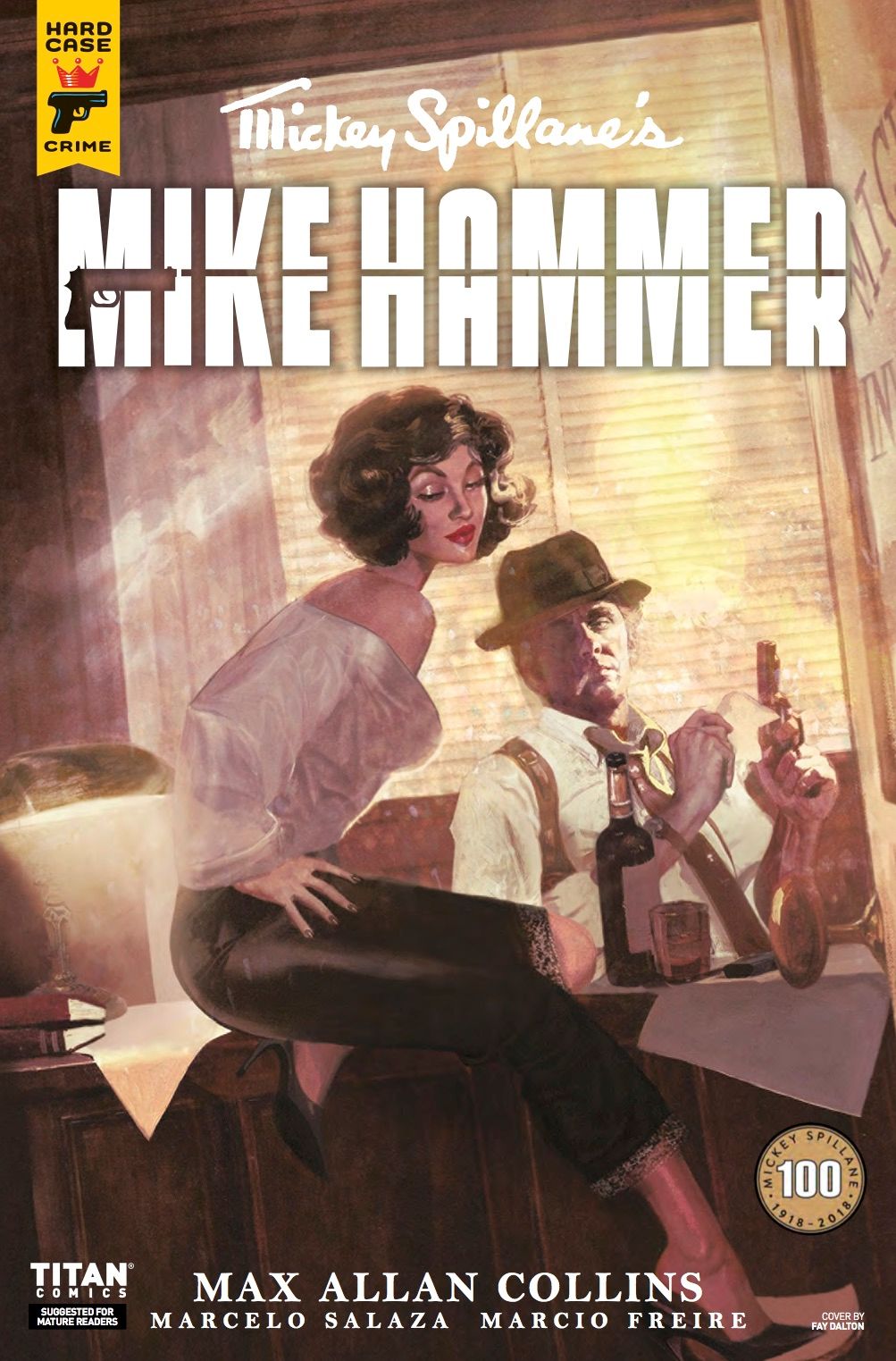

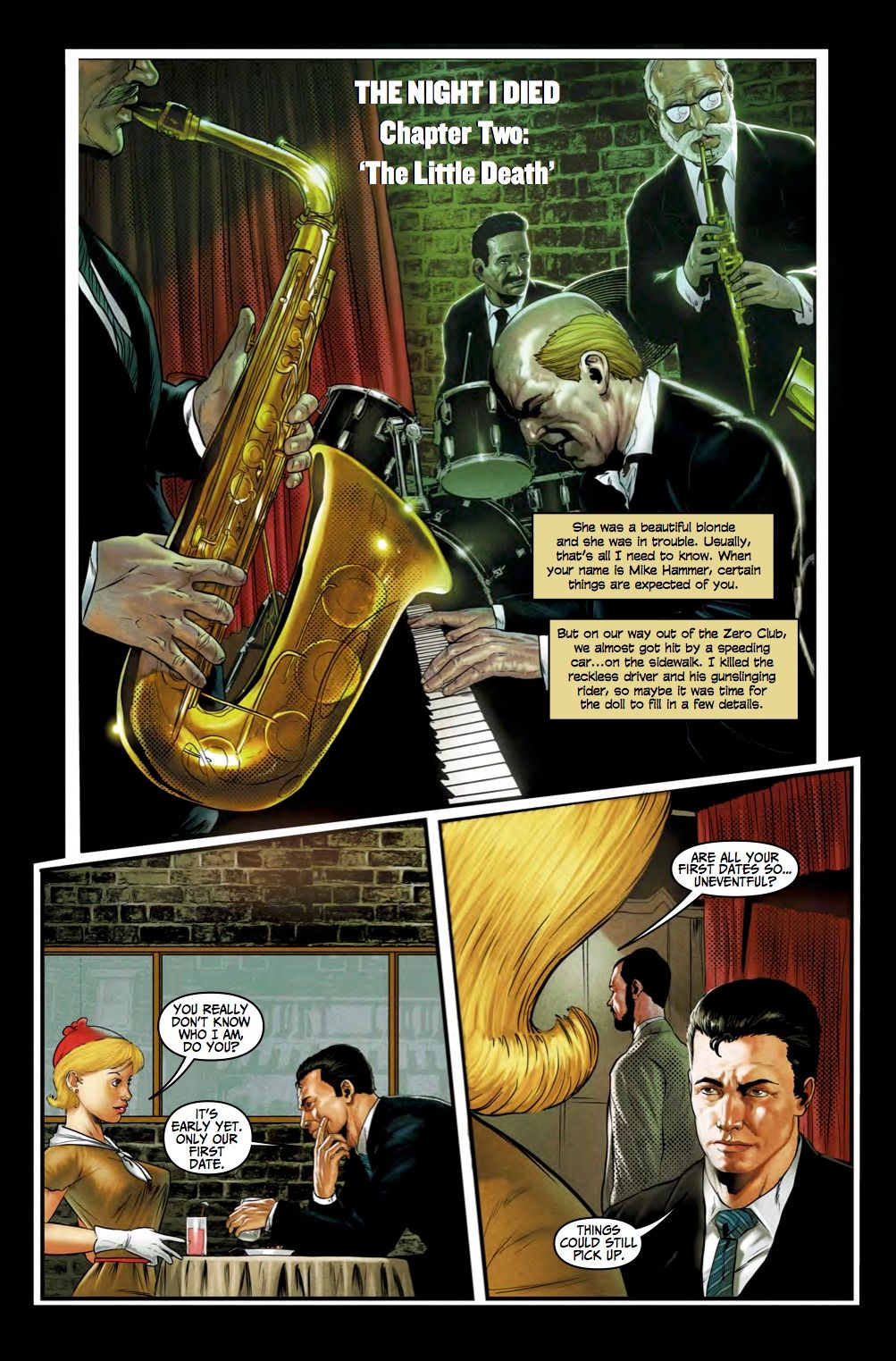

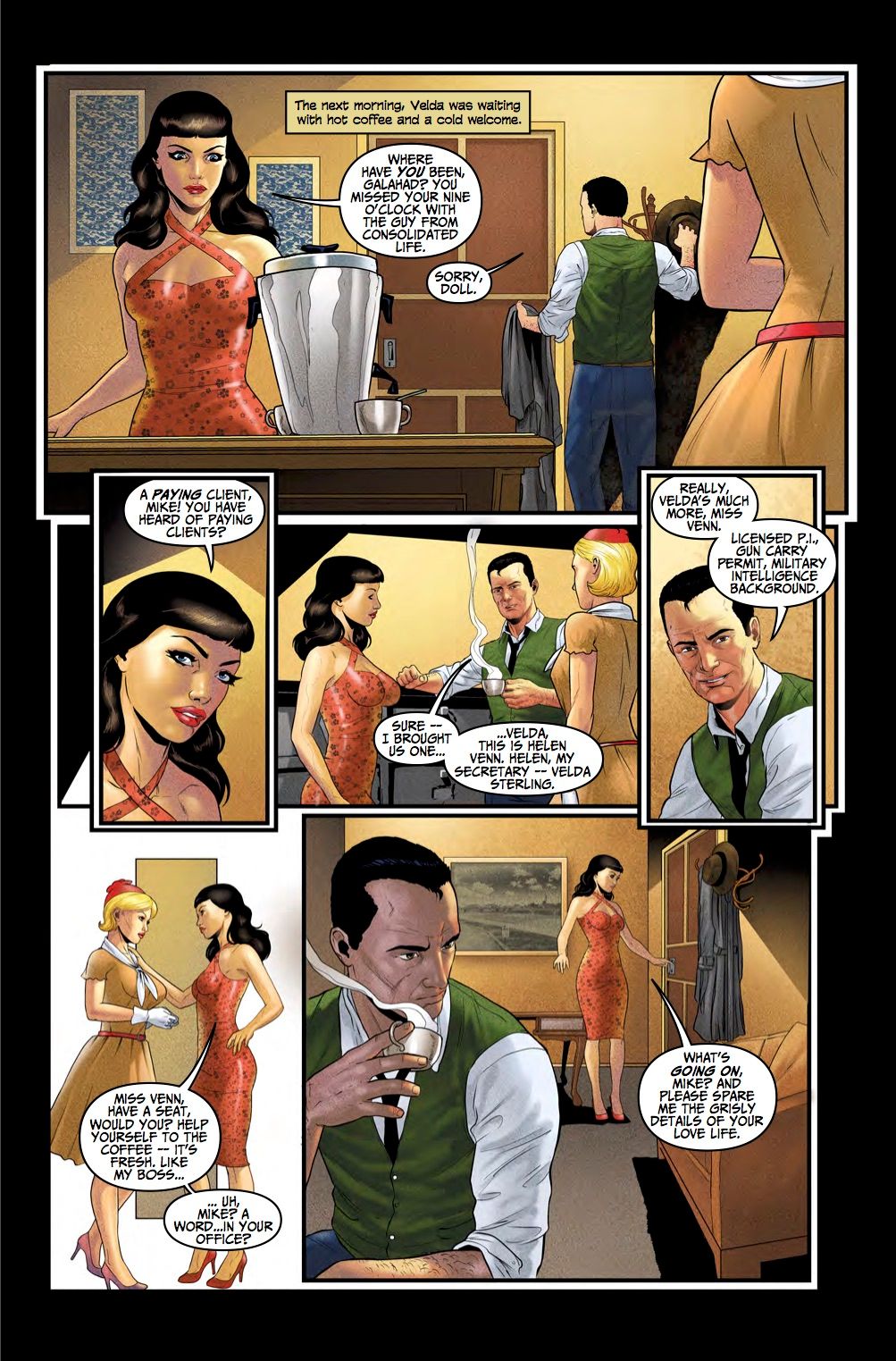

The latest story to come out of this unusual collaboration is Mike Hammer: The Night I Died, which Titan Comics is publishing under its Hard Case imprint (their noir imprint also publishes Collins’s prose novels). CBR had the opportunity to talk to Collins about this new work at Comic-Con International in San Diego, and we also have some exclusive artwork from Issue #2.

What's the origin of this story?

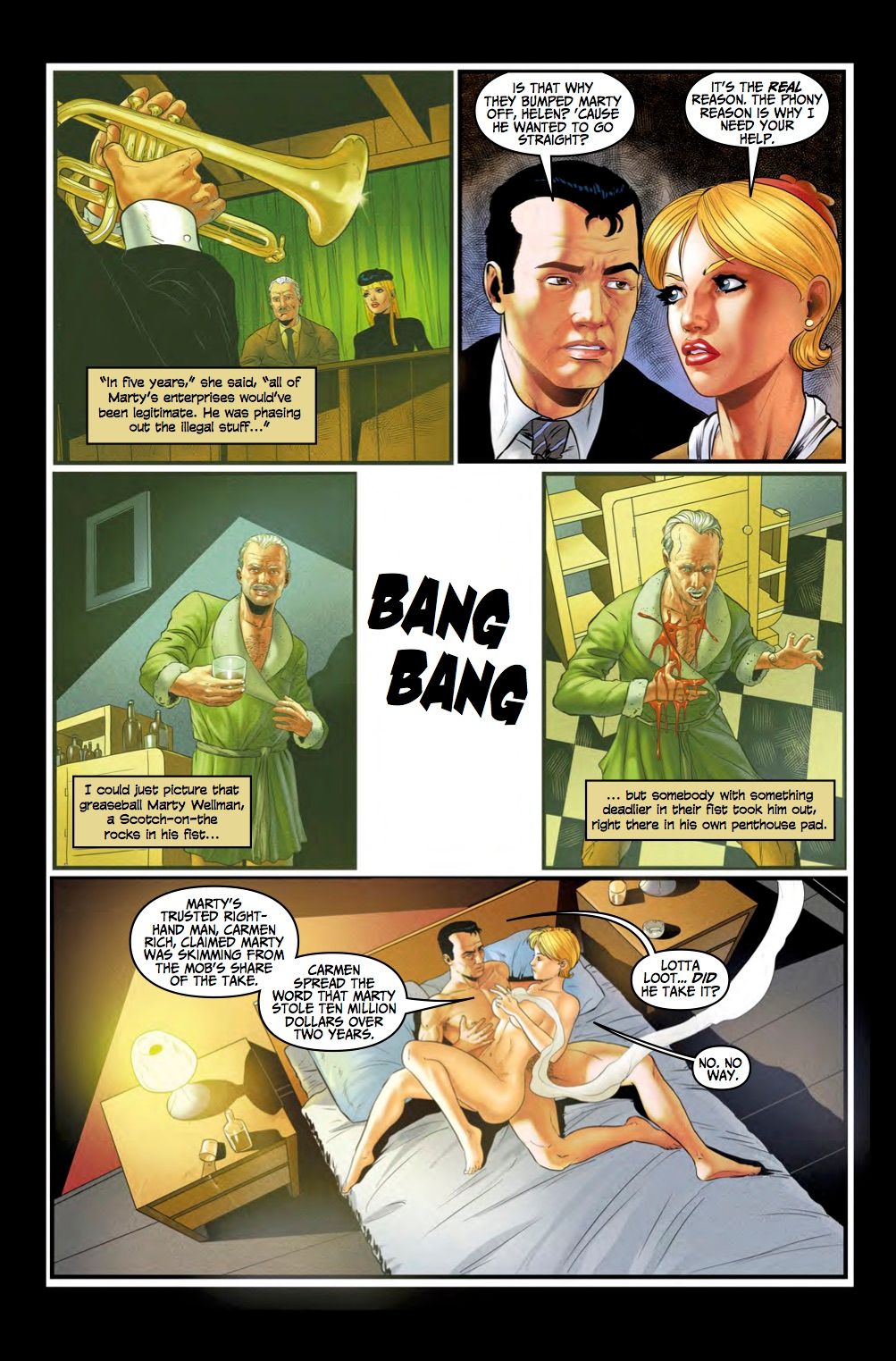

There was a radio show in the early '50s, and Mickey did a script for it that was not used. I found it in his files, and then I also found that he had done an hour TV version of it that expanded it. That was all in the early '50s. Then around 1995, with Mickey's permission, I took the TV version and expanded it and modernized it and turned it into a movie script, which for a while was going to be done by a guy named Jay Bernstein, who was the producer of the Stacey Keach TV show. So it was probably going to be done with Stacey. Then it went into a drawer, as certain things do.

What did you bring to this that wasn’t in the original?

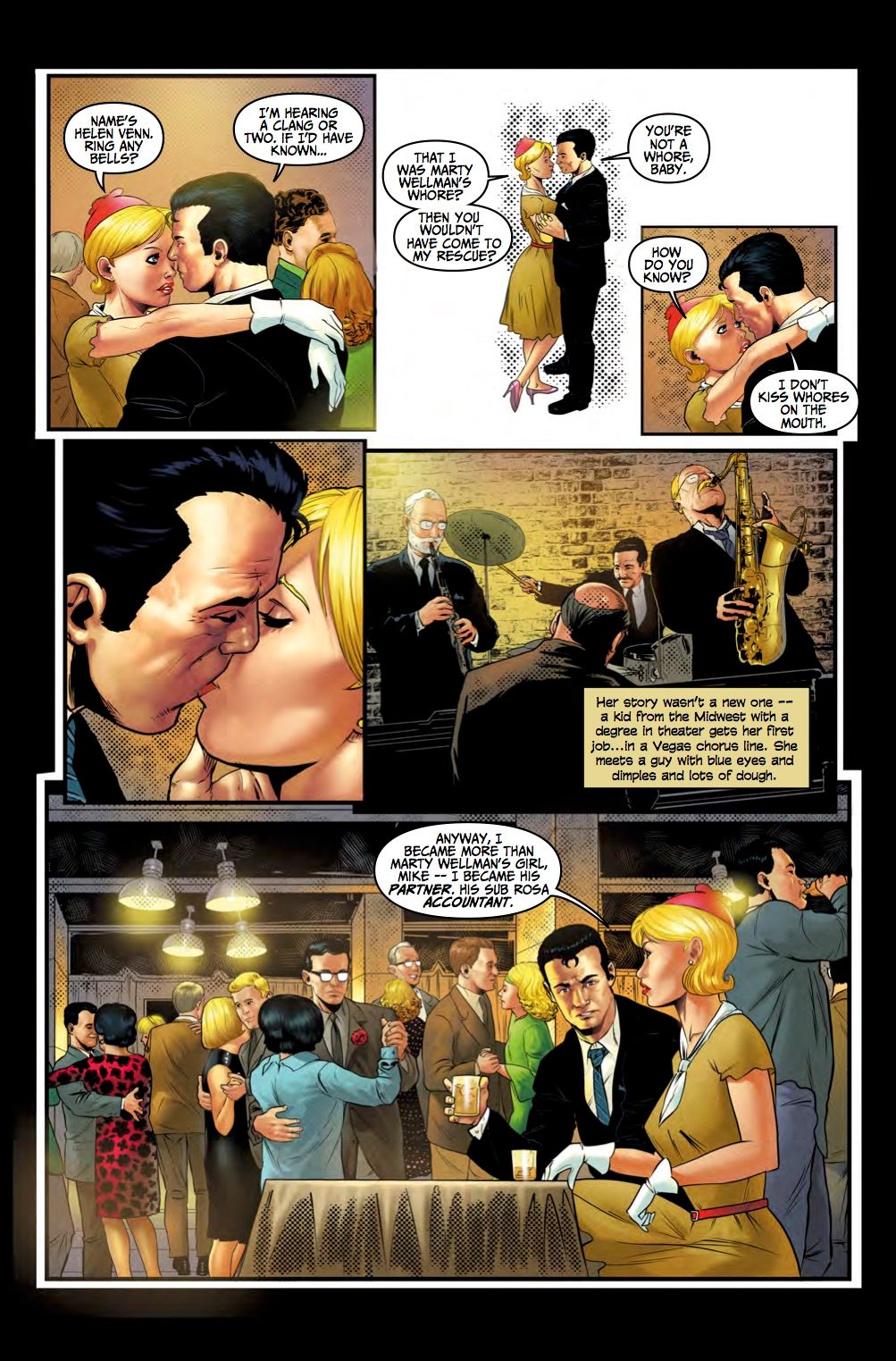

I tried to bring in elements of a typical Mickey Spillane story that maybe his earlier scripts didn’t hit all the bases. I wanted it in some level to be very reminiscent of I, the Jury, without just doing I, the Jury, but also to make sure we understand who the Velda character is, who I think is extremely important, and understand who Pat Chambers is.

[Mike Hammer] has a very small world. It’s really just his best friend, Pat Chambers, and his partner, Velda. Since Mickey even to this day gets accused of misogyny, it is very interesting to me that Velda, although she is his "secretary," is really his partner. She has a private detective’s license and she mixes it up. And they are very much in love.

Was that an element in the original Mike Hammer stories?

Yes, but it grew. It was something that built. It actually was a bit of a problem for him, because Mike Hammer was this randy character, one of the first guys who would sleep with women, but as he fell in love with Velda, that starts to feel wrong. The end game in The Goliath Bone, which is the last book chronologically, was that they get married.

So she has a more prominent part, then?

Yes, she has quite a prominent part in this. She gets rescued, but after she is rescued, I think she shoots more people than Hammer does.

That’s saying a lot!

You want to be careful who you kidnap, because people can sometimes get ticked. Particularly if Mickey Spillane created them.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='Max Explains How, Exactly, He Knows What To Do']

Tell me about how you write in his voice.

I get asked this quite often, and one of the things they ask me is “Are you intimidated?” because he was my hero when I was growing up. I took this stuff like vitamins. I don’t sit down and say, “I’m going to write like Mickey Spillane.” Some of that is already in there. My emphasis is to try to do the character right. And it's first-person. So if I do the character right, I don’t have to write like Mickey Spillane because Mike Hammer is writing the story.

But sometimes I do feel like there have been a few supernatural moments. I was sitting in my living room watching some of the crazy political stuff that’s on. I was working on the book, and I was about three chapters away from the ending. I grabbed a piece of paper, and the ending came to me. The last three paragraphs of The Goliath Bone is so pure Mickey Spillane, and it really did just arrive. I guess he wanted to write the last three or four paragraphs of the last Mike Hammer book.

What’s the first moment that you remember when you were going from working with him to doing something he was not part of -- when you took that first step off the diving board?

One of the nice things about the reviews for the books I have done for Titan is they’ll say “We can’t tell where Spillane stops and Collins starts.” I have always taken Mickey’s, say, 100 pages that I have to turn into 300 pages, and I don’t plop his 100 pages down and then write 200 pages. I take that 100 pages and I expand it, I look for scenes he skipped, and I put some of my English on the ball. I do more description than he does. I approach it as a collaboration. I don’t go in like I have been given eight of the ten commandments and I have to think the last two up and I gotta do God's voice. That’s not the deal. It’s that he said, “Max will know what to do.”

That’s quite a vote of confidence.

That's what he told his wife: “Round everything up, and he’ll know what to do.” I figure if he believed in me, I believe in me. I just try to make them the best books I can. Because I'm melded in there with his work, when I do take over, a couple of things happen. One is I have been in that world, so I just maintain that kind of dual voice, and the other one is that it’s almost like the way a rib eye steak is marbled with fat, you can't separate it. And that’s what you want it to be.

There are some elements of my work that get in there. I think there’s more humor. There’s plenty of humor in Mickey, but I think my Hammer is a little bit more of a wise guy. I can’t keep it out because that’s me. It’s supposed to be a collaboration.

There are certain elements that readers expect to find in hard-boiled novels. How do you balance staying within those expectations and breaking them to surprise the reader?

I have to admit that I don’t really sit down and say “It's a noir novel, so we gotta have a femme fatale, we gotta have this or that.” I just try to think of a good story, and because I'm in that noir context these are things that come along. You do want to play with people's expectations -- sometimes the obvious femme fatale isn't a femme fatale. One of the Titan books, I won’t say which one, seems to be leading up to Mike Hammer killing the bad guy and then he instead figures out that someone else has killed the bad guy and goes after that person. When he catches up with the person who killed the bad guy, he says “I just wanted to thank you for saving me the trouble.” You play with the expectations, have a little fun with it. And Mickey was so good on endings that you really have to write toward that ending. There's no extra chapter.

My wife Barb, who writes the Barbara Allen books with me, always says there's no Perry Mason scene at the end where Perry explains [everything] to Della and Paul -- and Paul says “Perry, why’d you have me drop a buffalo over the Grand Canyon from a helicopter?” You don’t get that because Mickey wanted it to be like a joke. There's a punchline and you’re out. He had great writing strategy, and I think I have learned a lot of his writing strategy.

When I'm doing an action scene it's pure Mickey Spillane, because that’s where I learned to write them. But otherwise I like to think that there’s a mixture of [Dashiel] Hammett and [Raymond] Chandler and James M. Cain and all these people I grew up on, and then I like to think there is some originality in them too.

Page 3: [valnet-url-page page=3 paginated=0 text='If You Want To Write For A Career, Learn As Many Mediums As You Can']

You mentioned the action sequences. The first couple of pages are wordless --

I wrote those pictures!

And then other sequences are very visual as well. How do you approach those when you are writing them?

I think thinking visually is what it’s all about, and I think with Spillane, because he was a comic book writer -- this is a guy who wrote Captain America and Sub-Mariner and all kinds of comic books, so he thought in pictures. And of course the screenplay this is based on is visual.

I had good responses to this, but I had a couple of people complain that when this story starts, you’re already at the end of a story. Well, that’s the idea. I wanted to bring you right into Hammer’s world and say: “We’re at the end of this adventure. This is who he is.” So at the end of this opening, you’ve seen how he deals with the bad guys.

You write prose novels and you write comics. Is there a difference between the two for you as a writer?

Well, I’m going to turn that around on you a little bit, because I get asked questions a lot by people who want to be writers, and they ask what advice I have, and my advice to them is to try to master as many different narrative forms as you can, because when the phone rings and someone says, “Can you do a comic book?” you want to say, “Yes, you bet I can do a comic book!” If Hollywood calls and wants a movie script, you say yes -- but you should be prepared, because these mediums are not the same. It’s storytelling that I love; it’s not necessarily the form that I love.

Sometimes I have the luxury of saying, “What would be the best way to tell this story? Would it be better in comics or would it be better in prose? Should it go straight to a movie script, because you can always turn that into a novel?” And then there’s the other thing where maybe the phone hasn’t rung in a while and they call up and they don’t have a novel. They have a comic book. And you’re a professional writer. You can say, “Yeah.”

With Road to Perdition, for example, I did two sequels in prose, and then I had one more book and I was not asked to do it so I went back to the comic book company and said “Would you like another graphic novel?” And they did the graphic novel. So it allows me to move if I have that ability to work in the different areas. And then I also think it keeps you fresh as a writer to be trying different things and reaching different audiences.

A part of Mike Hammer’s concept is that he is going to stay in his own time. He is not going to get a cell phone, is he?

Well, he does have a cell phone in the last few books, because Mickey wrote Mike Hammer in his lifetime. Mike Hammer in The Goliath Bone is a man in his late 60s, early 70s, so there are references to World War II, but when we decided to do the comic book, we really talked about it. We are not terribly specific about when the era is, but the idea is we’re late '50s, very early '60s. Now with the novels, the prose novels, I work very hard to figure out when Mickey worked on the story and to set it in there so there’s a chronology. And in the back of the Titan books, the novels, it gives a chronology -- if you’re one of those comic book people that wants to read the stories in order, start here. Even if they weren’t written in that order. In fact, we have a book out right now that was the very first Mike Hammer novel, it’s called Killing Town, and I found that in his files and completed it, so now I, the Jury is not the first Mike Hammer novel. Killing Town is the first Mike Hammer novel.

So you have participated in the first and the last. You’re like the Alpha and the Omega of Mike Hammer.

Or I’m the bread on a Mickey Spillane sandwich. [laughs]