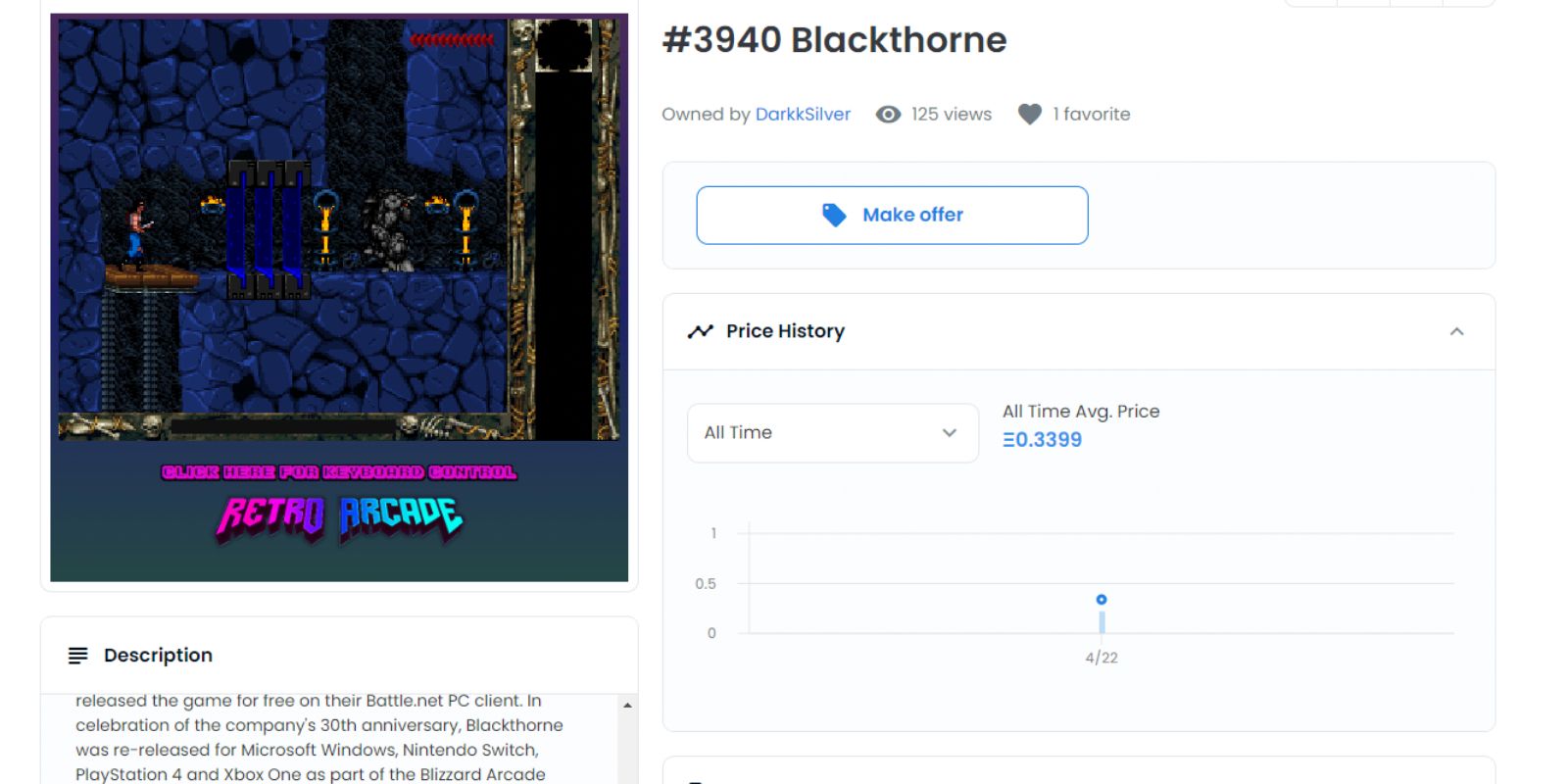

In early May 2022, MetaGravity released the Retro Arcade Collection, and this was noteworthy for two reasons. The first was the novel concept of playable software being minted as an NFT, a technology demonstrated with a collection of abandonware games and demos. The second reason is a lot less flattering: many of the titles that MetaGravity minted as NFTs still have owners that hold the copyright to them.In descriptions of the collection, MetaGravity claimed the games and demos in the NFTs were abandonware being "preserved" by their collection and would be available as playable software for two weeks. Abandonware is a term for games and software that are no longer sold or supported by their owners. There has been an increasing interest in preserving older titles that don't benefit from remakes and re-releases, with websites like Abandonia and My Abandonware dedicated to preserving games and software that are considered abandonware. Games are an artistic medium, and the preservation of art is a noble pursuit. The problem is that MetaGravity's insistence that the games they selected were abandonware seems to have been dishonest. Blizzard's SNES/MS-DOS title Blackthorne was initially released in 1994, but it has since been re-released in 2013 and as recently as 2021, making it a far cry from abandonware -- something that MetaGravity was aware of and even included in the NFT's description. It's hard to believe they would be ignorant of the fact that Blizzard's copyright ownership over Blackthorne wouldn't allow them to mint it as an NFT, even if it was just a demo.Within a week of the Retro Arcade Collection's release, many of the titles that consumers had enjoyed playing through their NFTs were taken down. Buyers who purchased from the collection still had their NFTs but not the original product they had been promised, as the demos and games are no longer playable. Even titles that are freeware (software that has been made readily available by the owners for free) had to be taken down. Just because software is free, does not make it legal to turn around and sell it as a product. One of the collection's inclusions was Remedy Entertainment's Death Rally. It was made freeware in 2021, but they still retain the copyright to that product.

The problem is that MetaGravity's insistence that the games they selected were abandonware seems to have been dishonest. Blizzard's SNES/MS-DOS title Blackthorne was initially released in 1994, but it has since been re-released in 2013 and as recently as 2021, making it a far cry from abandonware -- something that MetaGravity was aware of and even included in the NFT's description. It's hard to believe they would be ignorant of the fact that Blizzard's copyright ownership over Blackthorne wouldn't allow them to mint it as an NFT, even if it was just a demo.Within a week of the Retro Arcade Collection's release, many of the titles that consumers had enjoyed playing through their NFTs were taken down. Buyers who purchased from the collection still had their NFTs but not the original product they had been promised, as the demos and games are no longer playable. Even titles that are freeware (software that has been made readily available by the owners for free) had to be taken down. Just because software is free, does not make it legal to turn around and sell it as a product. One of the collection's inclusions was Remedy Entertainment's Death Rally. It was made freeware in 2021, but they still retain the copyright to that product.

It seems that MetaGravity's approach was to ask for forgiveness rather than permission. Instead of reaching out to make sure they had the right to mint these games as NFTs, they set up a form on their website that companies could fill out to request that MetaGravity take down any games in the collection. This approach is arguably understandable as many games that actually qualify as abandonware may not have a clear owner. Defunct companies, mergers, buy-outs, and expired contracts can leave some titles in a nebulous, uncertain space where it's next to impossible to figure out who, if anyone, actually owns them. Where this argument falls short, however, is the questionable product being sold to consumers and the selection of games presented. For example, Blackthorne and Death Rally have only ever been the property of Blizzard and Remedy, respectively.

Even with games and software that are considered abandonware, they aren't automatically legal to download or share online. The legality of downloading abandonware is usually on a case-by-case basis, but generally, software owned by a party that still holds the copyright isn't legal to download, even if it hasn't been available for sale or updated in many years. With the distribution of abandonware already being shaky ground, selling it for a profit is asking for trouble. That's why reputable abandonware sites offer their selections of games and software for free.

It isn't unreasonable for consumers to assume that sellers have the right to sell their products. While knock-offs and misleading merchandise are nothing new, it's a particularly troubling trend in online spaces and with NFTs. Sites like RedBubble and Amazon are filled with unlicensed merchandise and stolen artwork, but at the end of the day, consumers can at least count on owning a physical product. This controversy with MetaGravity's Retro Arcade Collection proves that the ownership of media minted as an NFT is not as concrete as sellers may want consumers to believe. There could even be legal consequences for anyone unfortunate enough to buy an NFT sold by parties with questionable legal rights to the product.

The ownership of cryptocurrency and NFTs has yet to be tested in a court of law, but there is a legal precedent for consumers being prosecuted for owning and sharing illegally distributed digital goods. When the music industry began retaliating against digital piracy, one of the measures companies like the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) turned to was filing suit against consumers that used file-sharing programs like Napster and KaZaA. RIAA has sued at least 18,000 individuals -- even targeting college students -- for pirating music. It's possible that this same logic could be applied to NFTs in court. Being prosecuted may not be a threat only to the parties minting NFTs of intellectual property that isn't actually theirs but also to the consumers who purchase them.