As longtime readers know, I often preach the virtues of “diversity,” whether in genre, style, or approach. Well, now it can be told -- apparently I have been channeling a “Meanwhile” editorial written by Dick Giordano (then DC’s Executive Editor) more than 25 years ago.

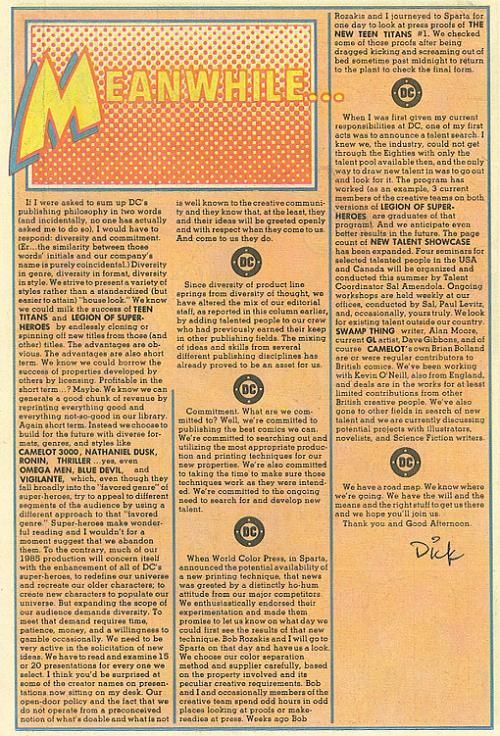

The editorial appeared in comic books cover-dated October 1984, which meant it was actually published around July of that year (August for books bought on the newsstand). Obviously the comic-book marketplace was vastly different then, with both DC and Marvel not yet fully invested either in the direct-sales market or in formats other than 32-page singles. Nevertheless, I thought Giordano’s points were sufficiently provocative to revisit.

Because Giordano writes in very long paragraphs, in the interests of clarity I have broken up the first section, and have also omitted a couple of paragraphs towards the end. Otherwise, here are the pertinent parts.

If I were asked to sum up DC’s publishing philosophy in two words (and incidentally, no one has actually asked me to do so), I would have to respond: diversity and commitment. (Er ... the similarity between those words’ initials and our company’s name is purely coincidental.) Diversity in genre, diversity in format, diversity in style. We strive to present a variety of styles rather than a standardized (but easier to attain) “house look.” We know we could milk the success of Teen Titans and Legion Of Super-Heroes by endlessly cloning or spinning off new titles from those (and other) titles. The advantages are obvious. The advantages are also short term. We know we could borrow the success of property developed by others by licensing. Profitable in the short term ...? Maybe. We know we can generate a good chunk of revenue by reprinting everything good and everything not-so-good in our library. Again short term.

[* * *]

Instead we choose to build for the future with diverse formats, genres, and styles like Camelot 3000, Nathaniel Dusk, Ronin, Thriller ... yes, even Omega Men, Blue Devil, and Vigilante, which, even though they fall into the “favored genre” of super-heroes, try to appeal to different segments of the audience by using a different approach to that “favored genre.” Super-heroes make wonderful reading and I wouldn’t for a moment suggest we abandon them. To the contrary, much of our 1985 production will concern itself with the enhancement of all of DC’s super-heroes, to redefine our universe and recreate our older characters; to create new characters to populate our universe.

[* * *]

But expanding the scope of our audience demands diversity. To meet that demand requires time, patience, money, and a willingness to gamble occasionally. We need to be very active in the solicitation of new ideas. We have to read and examine 15 or 20 presentations for every one we select. I think you’d be surprised at some of the creator names on presentations now sitting on my desk. Our open-door policy and the fact that we do not operate from a preconceived notion of what’s doable and what is not is well known to the creative community and they know that, at the least, they and their ideas will be greeted openly and with respect when they come to us. And come to us they do.

* * *

Since diversity of product line springs from diversity of thought, we have altered the mix of our editorial staff, as reported in this column earlier, by adding talented people to our crew who had previously earned their keep in other publishing fields. The mixing of ideas and skills from several different publishing disciplines has already proved to be an asset for us.

* * *

Commitment. What are we committed to? Well, we’re committed to publishing the best comics we can. We’re committed to searching out and utilizing the most appropriate production and printing techniques for our new properties. We’re also committed to taking the time to make sure those techniques work as they were intended. We’re committed to the ongoing need to search for and develop new talent.

* * *

[Here DG devotes two paragraphs to 1) new printing techniques, and 2) the variety of British professionals and New Talent Showcase alums then working on DC’s books. -- TCB]

* * *

We have a road map. We know where we’re going. We have the will and the means and the right stuff to get us there and we hope you’ll join us.

Thank You and Good Afternoon,

/s/ Dick

There’s a lot to parse in that, mostly in the first (extended) paragraph. Certainly Giordano’s double-barreled dismissal of spinoffs and reprints as “profitable [only] in the short term” jumps out immediately, because DC today devotes much effort (as does Marvel) to exploiting just those things. Giordano also eschews a “house style” and licensed properties; and talks up books which get away from a standard superhero model. Hard to argue against any of that.

To be sure, though, DC’s October 1984 books did include spinoffs (including “clones” of Titans and Legion), licensed books (Star Trek and Atari Force), and reprints (New Gods and the Best Of DC digest series). Giordano mentioned Omega Men and Vigilante as examples of “different approaches,” and that might have been true; but both books were also spinoffs of New Teen Titans. (Omega Men had a good bit of Marv Wolfman and Joe Staton’s Green Lantern in its family tree as well.) Other spinoffs included Infinity Inc., Batman and the Outsiders, and if you really want to get nitpicky, DC Comics Presents.

Even so, those “non-original” books didn’t particularly dominate DC’s lineup, which at the time included the non-superhero Arak, Arion, Sgt. Rock, and Swamp Thing, as well as the original runs of Warlord and Jonah Hex. Generally, I read in Giordano’s editorial a desire to develop DC’s “farm system,” for lack of a better phrase, in order to cultivate not just popular creations but loyal professionals.

Regardless, with all that’s happened to comics in the meantime, how useful is Giordano’s editorial to us today? Alongside the market’s ups and downs, DC has gone through periods of expansion and contraction, sometimes embracing spinoffs and “clones,” sometimes experimenting with eclectic, diverse books. Relationships with talent have been rocky too, from a flap over a ratings system a couple of years after this editorial appeared to its current alienation of Alan Moore. A DC “farm system” also sounds rather self-important today, considering the avenues which have opened up for comics creators in the past two decades. As for “diversity of format,” the late '80s saw DC divide its comics by price and paper quality. Today the vast majority of DC’s monthly books run $2.99 for 32 pages of story and ads, with little (if any) difference in paper stock.

Furthermore, the publisher has plunged wholeheartedly into the secondary market of reprints and collected editions. (Thanks to royalty issues and perhaps other matters of which I am unaware, DC apparently remains unable and/or unwilling to reprint certain material from several years in the 1970s and ‘80s. Ironically, this may cover works like the two Nathaniel Dusk miniseries* and the cult-favorite Thriller.) Again, that makes it hard today to understand Giordano’s argument that reprints are only good for the short term. Back in 1984, DC’s reprints tended to come in the form of digests, miniseries, and oversized special issues (like that year's 72-page Manhunter special).

Accordingly, Giordano’s editorial may work best to illustrate DC’s continuing struggle between a conservative approach and a more experimental outlook. Certainly today’s DCU publishing lineup looks very conservative, at worst geared specifically towards pleasing an ever-shrinking, ever-aging fanbase. Perhaps Giordano’s idea of diversity is most active at Vertigo, whose current business model depends both on monthly single-issue sales and the collected-edition market; and which is not reliant on a core group of long-running titles. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the Vertigo model would work for the DCU books, just that it seems to be working for Vertigo. Off the top of my head, I suspect that the DCU books help subsidize the other imprints. Such a relationship would necessarily reinforce a more mercenary attitude for the DCU books while allowing the other imprints to experiment.

And yet I come back to Giordano’s statements that “expanding the scope of our audience demands diversity,” which in turn “requires time, patience, money, and [an occasional] willingness to gamble.” Now, I cannot help but observe that this umpteenth column on diversity is being written while DC celebrates its Blackest Night-driven dominance atop October 2009's sales charts. Still, the question remains: what next? If Marvel’s Siege marks the end of its particular cycle of events, will Blackest Night likewise wrap up the various storylines which started with Identity Crisis (or even Donna Troy’s death)? Even Giordano’s editorial alludes to the sweeping changes just six months away in the pages of Crisis On Infinite Earths. Perhaps DC’s choice might be expressed more specifically as between “campaigning” and “governing”; that is, between Events designed to churn the marketplace, and storytelling which has less quantifiable goals.

“We need to be very active in the solicitation of new ideas,” said Dick Giordano twenty-five years ago; and today I suppose it depends on what you mean by “new.” In 1986, DC turned professionals like John Byrne, George Pérez, and Frank Miller loose on Superman, Wonder Woman, and Batman. (Marv Wolfman and Jerry Ordway and Mike Barr and Alan Davis also had memorable tenures on the World’s Finest heroes.) In 1987, Mike Baron and Jackson Guice helped the new Flash find his way; and Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, and Kevin Maguire shook the stodgy out of the Justice League. Indeed, for most of the rest of the decade, DC traded pretty heavily in revamped and/or relaunched takes on familiar characters and concepts, and most were received pretty well. (In this respect DC hit something of an exacta with the Shadow, since both Howard Chaykin’s miniseries and Andy Helfer and Kyle Baker’s ongoing offered wildly updated takes on a licensed character.) Some, like Sandman and Suicide Squad, shared only a name and a general concept with their predecessors. However, the truly original books (Amethyst, ’Mazing Man, Electric Warrior, Wasteland) didn't have a particularly long shelf life -- and again, for whatever reasons, haven’t been revived in collections.

Accordingly, it’s easy to look at DC’s history since Crisis and see that the safest bets are with the familiar superheroes. The publisher’s success at putting familiar faces (back) in familiar costumes has been front and center the past few years, first with Hal Jordan and Barry Allen and now with Dick Grayson; and now with Blackest Night we see that all coming together under an Event umbrella.

But how long have these elements taken to converge? If Blackest Night is the culmination of a journey whose first step was six or seven years ago, does that mean readers must wait another several years for a similar payoff? Does DC really want to build the bulk of its publishing around long-term buildups which produce short-term gains?

Clearly not; and clearly that’s not how DC views its current strategy. Maybe Blackest Night and the new Batman really are expanding DC’s readership. Maybe DC has looked so deeply into its own navel that it’s come out the other side with more accessible books. If all this has actually made DC stronger, I can’t really argue.

If not, though, I still think Giordano’s editorial contains some solid fundamentals. At its heart is the notion that ultimately, all that matters is producing good comics. Sure, Giordano’s assertion that “we’re committed to publishing the best comics we can” sounds rather obvious; but when it’s fleshed out with talk about new approaches and fresh talent it picks up a little more steam. DC’s 1984 line was in transition, not only between sets of market conditions but between creative approaches; and history shows that it didn’t quite live up to the ideal described in Giordano’s editorial. (The spinoffs and clones of the early '90s definitely didn't help Giordano's arguments.) Still, that’s no reason DC should dismiss Giordano’s words, regardless of the differences the years have brought.

It’s probably obvious as well to assert that good comics are timeless; but in a very real sense that’s Giordano’s point. I wouldn’t be surprised if two of those anonymous proposals he mentioned were The Dark Knight and Watchmen, each now perpetually in print. The true test of Giordano’s legacy is the longevity of such works, whether they have been collected in more permanent forms or survive only as memories.

Dick Giordano was DC’s Executive Editor for some twelve years, from 1982 through 1994. During that time DC reinvented pretty much its entire superhero line, while establishing new imprints such as Vertigo, Piranha, and Milestone. This was one of the most fertile creative periods in the company’s history, and although the excesses of the early ‘90s speak for themselves,** I’d like to think Giordano’s principles of diversity and commitment weren’t forgotten. Today, as DC enters the home stretch of its latest round of events, it should honor those principles in hopes of doing even better.

+++++++++++++++++++

* [Nathaniel Dusk was a four-issue private-eye-noir miniseries (February-May 1984) written by Don McGregor and drawn by Gene Colan. It was noteworthy for using only Colan's pencils, and was popular enough for a sequel (October 1985-January 1986).]

** [I won’t try to speculate whether he felt completely faithful to this “Meanwhile...” in the ten years following its publication; but he did recently apologize for helping usher in the “grim ‘n’ gritty” trend.]