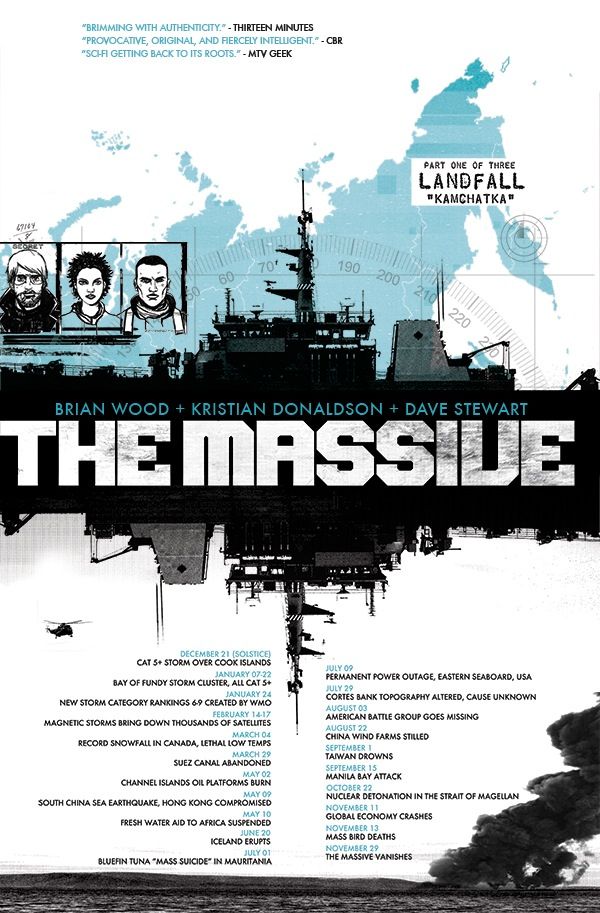

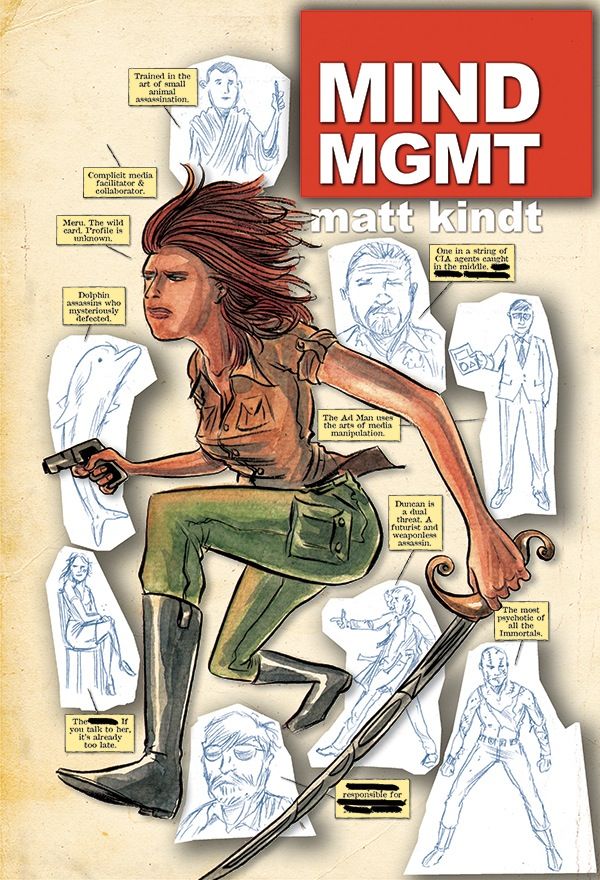

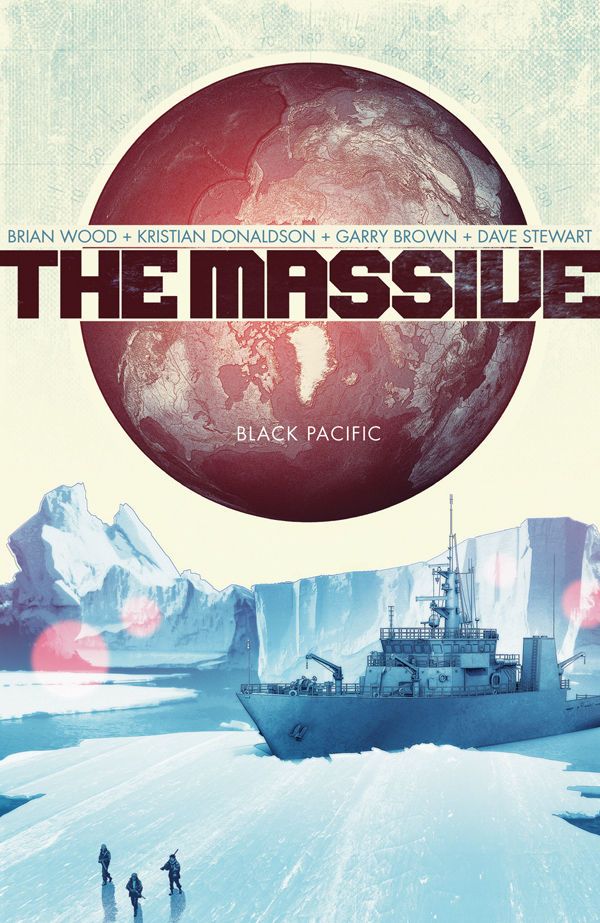

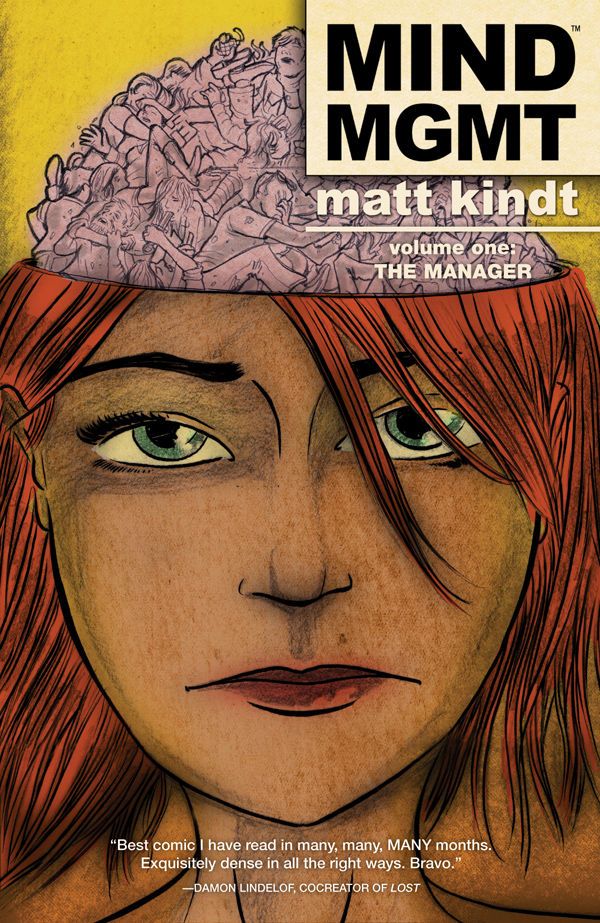

In March, Dark Horse will reprint the first issues of Brian Wood's The Massive and Matt Kindt's MIND MGMT at a special $1 price. The Massive follows a group of environmentalists after the Earth undergoes a massive ecological disaster, while MIND MGMT is the story of a group of psychic super-spies and a journalist who's pursuing their story. Both reprints will be listed in the new Previews catalog, out Jan. 30, but we have exclusive cover reveals here. And, to make it more fun, I started an interview with Wood and Kindt, and then let them take over.

Robot 6: Each of these comics is set in a universe in which one thing has changed significantly; in MIND MGMT it is not clear right away what has happened, while in The Massive it is obvious, at least in its outer manifestations. What was your inspiration for these, and why did you think they would make for interesting stories?

Matt Kindt: I'm not sure that there is one significant change in Mind MGMT so much as there is just a specific genre choice I made. I try to pick one thing, whether it's spies or crime or science fiction (in the case of MIND MGMT) and sort of apply that to real characters/people and see how they'll react. To me it's more of a "what if" scenario. What if you grew three stories tall? (3 Story) What if you were a spy and hated being one? (Super Spy and 2 Sisters) What if the abilities of the mind were pushed past any known limit? (MIND MGMT) That's usually where I start and then just create some personalities to populate and react to my “what if.”

Brian Wood: It's sort of the same thing Matt said. I find a lot of pleasure in creating very flawed, very relatable characters and then putting them through the worst situation possible. So that’s a version of a "what if" story, but in the case of my big world-building books it's a really exaggerated "what if," usually involving war and the end of the world. The character dramas, though, those are universal in any setting.

Since these are first issues, you have to give the reader a lot of background information about everything that has happened before the story starts. How did you come up with ways to do that?

Kindt: I've tried to use the format of the comic itself and the design of the issue to give me a little more space to tell the story and build the world. There is a "MIND MGMT Field Guide" that runs up the side of every page that is sort of a manual for “how to be a MIND MGMT agent.” And there are two back-up stories, one on the inside covers and the other at the end of the main narrative that branch out and begin to reveal other supporting characters. In addition to that, I'm lucky enough to have a format where I don't have to have ads—so I've designed my own back cover ad that seems real but also begins to put some layers into the story and backstory.

Wood: Well, one of the things I learned from writing my DMZ series is not to be too mysterious at the start when it comes to backstory and world-building. So for The Massive I drop the reader in the deep end right away but keep cutting away to give context and a bit of history, so by the time that first short arc is done, the background is there.

I also did a bit of backmatter, not exactly stories, but in-series information and additional narrative information that builds the story out a bit more.

What do you think is the best way to introduce your characters to the readers?

Kindt: Just by dumping the character and the reader into the situation. Any situation really. But there's also some fun to be had with that as well — by playing with voice over narration and the voice of the narrator in general you can set up expectations and then bring them all crashing down.

Wood: Give the reader a point of access, have the character do something relatable, or be in a relatable situation. Having said that, it's possible I didn’t follow my own rule right away in The Massive #1, but it's still a good rule!

You have very different approaches to the pictorial space of the page; what defines your approach to paneling and composition? (Brian, I know you work with an artist, but I assume you do thumbnails?)

Kindt: I think storytelling and pure cartooning are the most important thing. Is there pacing? Is the reader able to read through the issue in a controlled way that keeps up the pace and doesn't bog down? I hate tons of heavy text pages and I hate splash pages by themselves — they tend to slow the reader down too much, or, by contrast, make the reader flip the pages too quickly. There's a balance there that I always am conscious of. In addition to that I think color and paper choice are just as important as anything else. I really like making a comic that, when you're holding it, makes you feel like you're actually holding a piece of the story. Like you've picked up a document that you maybe shouldn't be reading and maybe isn't all that safe to be seen with.

Wood: I don’t thumbnail when I write, but coming from an illustration education and background, I am composing the page as I write, keeping an eye on space and panel counts and the page- urn, making sure text-heavy panels are also visually simple panels to allow for space, etc. I probably do too much of that, actually, but I can’t turn it off.

In the end I always defer to the artist if they have a better way to go. That’s the OTHER thing being an artist myself has taught me, when it comes to collaborating.

Let’s talk about format a bit: Dark Horse is offering these Issue #1s as a way to introduce new readers to the story. Why do you think that is preferable to waiting for the trade?

Kindt: I don't think it always is a preferable way to do it. However, I've really made an effort to make the individual issues the true reading experience. The collection/TPB is secondary. It's the first time I've done a "standard" comic book format and I chose that format deliberately. Publishers, agents and editors tried to talk me out of it but I really had to kind of insist on it. I had an idea that fit the format and doing it as a book first would have just watered it down. I want to write something serialized that is read in monthly bites. The collections will still work but they'll work more like watching an entire season of Breaking Bad in one evening rather than spreading it out over the course of a few months.

Wood: I see the collection as the primary format, actually. It’s certainly the permanent format, it’s the format most readers will read the story in, and it’s the format that gets translated and published around the world. Compared to the single, which has a limited release and, at best, a few months on the shelf, the collection can last for decades.

That said, The Massive is the first time in a long time I’ve put as much oomph into the singles as I have. I’ve gotten used to the fact that, in my career, my singles will sell 8,000 copies and the collections, eventually, over 100,000. So I wrote accordingly. But I wanted people to walk away from reading a monthly Massive comic feeling like they got a lot of bang for the buck. A lengthy, substantial read. So to that end I have dense stories in shorter arcs with a lot of those as one-shots.

Matt, you even mention in your intro that you don’t read floppies. Why is that, and has making one changed your attitude? Do you read floppies now?

Kindt: It's changed a little but not really. I still think most monthly books are written with the collection in mind. Which is fine, because those will end up being good reads. The problem now is that I get a lot of the monthly mainstream stuff for free so I'm reading it monthly again, but I'm not sure I'd buy it monthly. But a lot of the reason is I'm so busy working making comics that I don't have time to keep up monthly. I'm sure the guys at my local shop think I'm a deadbeat pull customer — but I do come in and buy up a bunch of stuff every month or so.

Brian, you have talked in the past about different ways to make single-issue comics unique, to provide something other than what is in the trades. Have you done any of that with The Massive?

Wood: I have written supplemental backmatter for The Massive, material that’s unique to the single edition. It’s all part of this goal to beef up the single issue reading experience. I did that for the first six issues, and after a short break, will continue producing that material but for the web, for everyone to read.

And for both of you, how does the monthly-issue format affect your storytelling?

Kindt: It's definitely more of a constraint than I'm used to. Writing graphic novels is relatively easy. It begins and ends whenever I feel like it should. The chapter breaks are arbitrary and just end up breaking naturally. With a monthly book it's got to be like what it's like writing an episode of a television show. The pacing has to be just right, get enough information in that particular "episode," and end with both a satisfying conclusion but also a thoughtful teaser that leaves you hanging. Each 24-page installment has to do a lot more heavy lifting than any 24 pages in a larger book. And that's the fun of it to me. It IS different than what I've been doing for years. And that's the appeal. It keeps me on my toes and keeps me thinking differently about everything I'm doing. It keeps me interested when my goal every month is to make something in that format that hasn't been done yet/ever.

Wood: I started my career off in comics as a graphic novel writer, but for the last 10 years I've been writing almost exclusively monthlies. Come to think of it, in all that time I've done only two slim graphic novels. So the monthly format is the norm for me; I really have nothing to compare it to. I've really come to love it, frustrations and all.

Since I am NOT a comics creator, I’d love to hear a bit of shop talk between the two of you about the challenges of writing comics and what you think worked particularly well — or didn’t work — in these comics.

Kindt: Brian, I don't know about you, but the things I struggle with from month to month are keeping my head straight. I'm writing MIND MGMT but I've also been writing some stuff for DC and Marvel, and switching gears is something that I definitely have to consciously do. That took some getting used to. I have a week or two where I have to just switch my head over to MIND MGMT completely — I think about it before I go to bed, when I wake up and when I'm in the shower (that's where a lot of the best ideas come). Then I have to set a day or two aside to only think about Frankenstein or Spider-Man or whatever else I'm working on. But I've definitely had to make that mental space between projects so I can give them each the time they need.

That's something I had to learn on the fly. I just assumed I could write Spidey in the morning and MIND MGMT in the afternoon, and that's pretty hard to do. But doing only comics and not having to do any design or illustration work leaves me plenty of time to get my schedule in order.

The other big challenge on this kind of monthly series is that it's bigger than anything I've ever done. The longest complete work I've ever done was Super Spy at around 270 pages, but when MIND MGMT gets to the end it'll be around 900 pages. That's a lot of comics.

And finally, the one thing I always thought was kind of strange was reading reviews for single issues of comics — and now that I'm doing one, I kind of love/hate it. It's great, because you end up getting more immediate feedback and you can tell what is working and what readers are reacting to immediately but on the other hand, there's a stressful couple of days every month when you're waiting to see how the issue is received. That call and response is ultimately what makes the monthly experience more satisfying than anything else I've done in comics.

Wood: Switching mental gears is a trick, to be sure. I’m writing five monthlies right now, which generally means that in any given week I have my hands in two different books, and sometimes, like around big holidays like this, I’m working on different books within the same day. I keep extremely detailed notes, longhand, in books dedicated to each series, so when I switch gears I can do it much easier by reading cheat sheets and getting up to speed immediately. Having a good editor is also very important.

The biggest frustration comes from the business side of it all. Dealing with, or at least worrying about, low sales, contract bullshit, news cycles, foreign rights, media rights, royalty statement irregularities, red tape, editorial drama and so on. I am very hands-on, on the business side (often to the surprise of new editors and publishers) and put as much effort into maintaining that side of my career as I do the creative side. And it's frustrating ... the business of comics does not follow the same rules as the rest of the world, and having to make that allowance wears me down.

Matt, you need to break that habit of reading reviews ... no good will come of it. It took me FOREVER to learn that and to break the habit — a habit forged as a small-press guy who often had to go out and do my own PR, as maybe you did, Matt. It's just pointless — we're writing for ourselves first and foremost, and literally every single one of my elder peers has warned me never to read reviews. It's taken me most of my career to learn that, but the feeling of not doing it has had a noticeable affect in my overall mood.

Lastly, and this is something that comes from my wife, who is not only a business owner but also someone who knows nothing about comics except what she sees from me: This is a job. This is a business, not a hobby or a social activity. That may sound a little cold, and it doesn't mean I don't get immense creative satisfaction from doing what I do (if I didn't, I'd go be a stockbroker or something) but it's about finding the right balance. Not making business decisions based on being a fan, or social pressure, or making too many allowances for the quirks of this industry. I’m 41 years old, this is my life, this is what I've committed to and made the promise to feed my babies by doing, so to say I take it all drop-dead serious is actually an understatement. So I keep a sharp eye on the business, find great friends within the industry and plenty others outside of it, and write the hell out of the comics I write. The right balance and perspective allows me to find the fulfillment in this career and keep the B.S. to a minimum.

At this point, Matt and Brian took over and started interviewing each other.

Kindt: You have kids (I think?) — ever thought of doing a kids' book/comic/GN? I ask because I have a 9-year-old daughter and I'd love to do a book for her but I've been having a lot of trouble writing something that satisfies both my needs as a creator and her interests as a reader. I'm sure there's a way to do it, I just haven't figured it out yet.

Wood: I have a 6-year-old daughter, and she’s only recently been reading on her own ... maybe the last six months. Comics are a hard thing for her to figure out, visually, and honestly she has so many things already to read that I don’t push it. Also, I think one of the keys to my continued sanity is to keep my work life and my family life completely separate. I value being able to “clock out," shut my office door, and leave all that behind for a few hours while I hang out with the kids. I imagine as they get older (I also have a 2-year-old) that'll be harder to do.

I do look forward to the day when my daughter can at least LOOK at something I’ve written.

Kindt: Don't you think every writer should take some design classes and be forced to draw at some point in their life? (Leading question, I know.)

Wood: I think any writer that has some sort of visual arts training is probably a better writer than if not. I'm sure that sounds snobbish, and there's bound to be exceptions, but I think it's only logical. Being aware, if only on a basic level, what it's like to have to compose a page of comics will help everyone involved in the process. I have a BFA in Illustration, and I have a lot of pride in the fact that the artists I work with can tell that about me. It also helps me feel less bad about still being $45,000 in debt from college ... I’m using my degree!

You obviously do both and have been for a while, but now that you’re writer-only on some DC stuff, how hard has it been to write for another artist, and to give up that amount of control over the finished page?

Kindt: It's actually the most fun part. Writing is easy. It's the freaking weeks of penciling, inking, coloring that sap all my energy. So handing that off to an artist to take care of was a strange kind of relief. It's been fun collaborating and letting an artist tweak a layout or come up with a different way of showing what I was imagining. I end up doing thumbnails before I write the script, but those are only for me. I write visually first. I can write a script without thumbnails, but it just takes longer. I end up sitting there trying to picture the page and the action rather than actively imagining it with a pencil and thumbnails. So thumbnails end up saving me time. But I never show those to the artist — 'cause as an artist I'd hate having thumbnails given to me.

Do you think the WAY you break into comics is important to how your career ends up going?

Wood: I don’t know ... Maybe in extreme cases? Like, if you break in through pure luck, or by being an asshole, or through some other way that doesn’t involve having a strong work ethic and a lot of patience, sure, it's not going to go well for you. But if you mean whether or not to break in self-publishing and going the small-press route versus hitting the jackpot and launching a career at DC or Marvel ... I think there's pros and cons to both, but once you're in the door it's sort of up to you what happens next.

Kindt: Why is the end of the world so cool?

Wood: Vicarious living combined with deep-denial guilt because with every minute of our day we're doing something to ruin the planet.

I love hearing how other creators structure their day, especially when they have kids. What's the schedule? How many hours a day, or a week, go into making comics?

Kindt: That's the true hardest part. The beauty of making comics is that I get to stay home all day and work. I don't have to leave the house unless I want to (cabin fever). My daughter is 9, so during the school year my schedule is 8:30 a.m.-3 p.m. weekdays while she's in school. I stop working when she gets home and we do family stuff. I usually skip lunch (by forgetting to eat) during those days. When I get super-swamped or behind I end up having to go back to work again at bedtime around 8:30 or 9 until whenever I get done.

During the summer it's really hard. Between comic conventions and family stuff I really have to just set times and days aside where "daddy's gotta work." I'm lucky also that my wife is a freelancer so we're both home and can swap work days in the summer.

And my daughter is old enough now that she gets an allowance, but instead of taking out trash or something she gets paid to scan my artwork in and paint the flesh color on all the characters. So in that way I find that letting work and family mix can be a good thing. I feel like we're showing our daughter a different way to live. Where you don't have to go into the office somewhere every day and only have weekends and evenings off. And having her see us actually enjoying our work — to the point that it really isn't "work" — is important.

Wood: Do you do conventions or signings? How much of that is too much, do you think?

Kindt: I do probably eight conventions a year on average — all over, East and West Coast. I started doing them when my first book came out in 2001 and I just started seeing that as another aspect of the "business" part of the job like you were talking about. I think it's just as important as contracts and publisher relations, etc. To me it's the equivalent of being in a band that has to tour and play shows and meet fans, etc. I don't think you can do too much. Every year I say I'm going to take a year off because I'm exhausted by the end of it, but then I take the winter off and I don't mind going back out again in the spring. It's hard, though.

But to me that goes hand in hand with reading reviews. I never understood not reading reviews. It's like shooting a gun with your eyes closed. Did I hit the target? Are people getting what I'm trying to do? Is it too complex? Does it make sense to anyone but me? Those are the things I think matter. It's the difference between a play and a movie, really. That immediate feedback (relatively) from the audience is fun and it also lets you know what's working and what people are reacting to. At the end of the day I start out doing a comic for myself—to make the perfect comic that I would love to read. But by the end of the process I've thought about it and worked on it so much that I can't stand reading it. So readers enjoying it for me is critical to my process.

Wood: I do a fair amount of writing longhand in a notebook, usually in bed. How much of what you do is dependant on technology or being chained to your desk? I heard a story about a prolific comics artist who draws on a fold-out table in front of the TV eating a bowl of cereal.

Kindt: Ha! I have one of those fold-out tables and I usually do all my painting/coloring on it in front of my giant TV. Coloring is SO boring. Honestly, it's the most mindless part of the process, and I can't get through it anymore unless I'm watching something while I do it. And it's the only time I really get to watch TV so I actually look forward to it now — watched Homeland during the last issue and it was great! That said, most of my process is by hand. I print a ton of pages with a nine-panel grid — each panel is a page of the comic. Then I put that in a binder and thumbnail out six issues at a time. I love the binder because I can sit in a coffee shop or in bed or where ever I feel like. Working in bed is the ultimate perk of our job, right?