Mata Hari is a fascinating character: an exotic, enigmatic woman who used her fabled powers of seduction to extract secrets from the enemy. Or did she? Peel away the veils of history, and her story looks very different; modern scholars see her not as an unscrupulous spy but as a victim of politics and the sexual mores of the time.

RELATED: Karen Berger Aims for ’Something Different’ with Berger Books Lineup

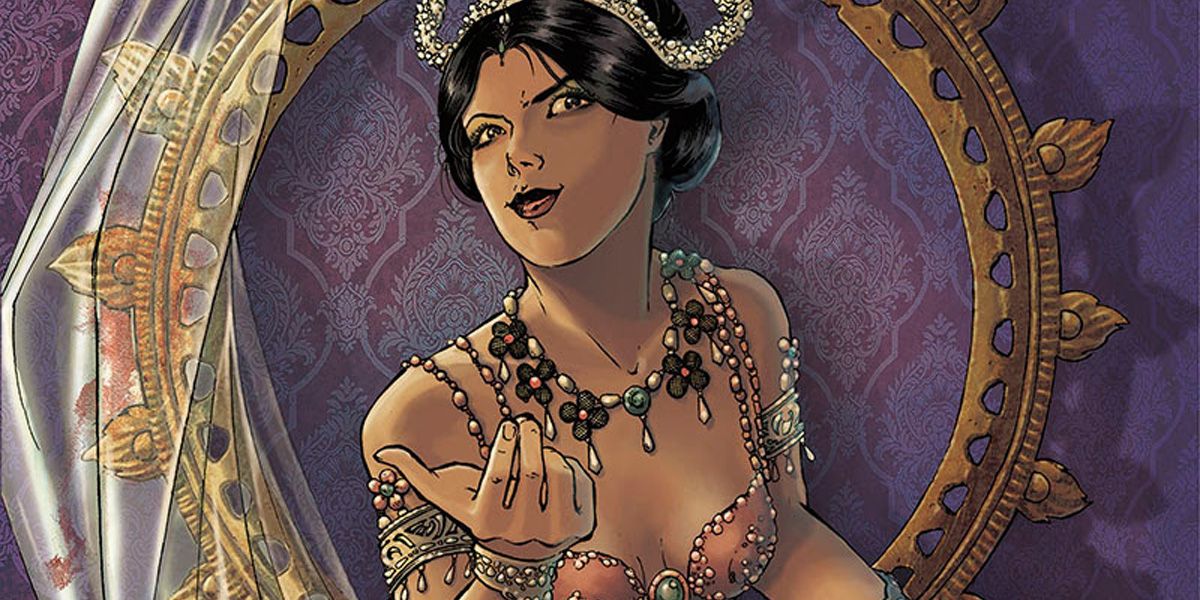

There's another view: Mata Hari, a.k.a. Margaretha Zelle McLeod, the person, who lived from 1876 to 1917. In the five-issue series Mata Hari, part of the new Berger Books line from Dark Horse Comics, writer Emma Beeby, artist Ariela Kristantina (Insexts) and colorist Pat Masioni tell the story of Mata Hari from her own point of view -- although, and this is part of what makes her so interesting, she is the ultimate unreliable narrator.

CBR talked to Beeby about what it was like to go deep into the story of the world's most famous spy for Mata Hari, which debuts in February.

CBR: How did you first hear about Mata Hari, and what interested you initially? How has your view of her changed from your first impression?

Emma Beeby:: I have no idea when I first heard of her. She's part of the popular consciousness, this femme fatale archetype -- a spy, a seductress, someone daring and amoral. A female Bond, or something. I happened to come across a biography and wanted to read about that. But she was more interesting and extraordinary than even that expectation. She says she's a princess, she runs away to the circus, she goes from disgraced penniless girl with no prospects to the toast of Europe, only to fall back into disgrace as a double agent and is executed. There's a bit of everything in her story: rags to riches, classical tragedy, Icarus fable, sex and spectacle, plus all the patriarchal crap she deals with makes it feel very relevant to what's happening in the light of #MeToo. I try to connect to the best and worst of her. I don't want to hide the bad to show her in a better light. She did that, but I won't.

How did you come together to do this story?

I loved Ariela's work, particularly on Insexts, and sent some of that to Karen. We agreed she'd be perfect, we wanted to try to get her on board, and thankfully Ariela said yes! We're all continents apart, so mostly we talk by email, but we did manage to meet up last year at a convention, which was lovely, and not just because Ariela gave me an early watercolor version of the first cover, now proudly displayed on my wall.

Last October was the 100th anniversary of Mata Hari's death. I know the French government was supposed to declassify some of their documents on her. Did any of that play into the story?

I was already into the writing by then, and the more I read about the farcical foregone conclusion of the trial, the less value I saw in trying to learn more about the case than was already out there, beyond doing it for my own curiosity. There's some weird things in the case that maybe will be revealed in those documents: like the key evidence of telegrams that seem to conclusively name her as a German spy, that were sent in a code the Germans knew was broken. The originals apparently disappeared, several had dates that didn't match up, and not all of them made it to the investigators. Maybe there's more pieces of evidence to go through like that. The trouble is, the case was never about the evidence. So, I leave going through all that to historians!

What sort of other research did you do? Was there anything that surprised you?

I read biographies, newspaper articles from the time, anything and everything, barring fictionalized accounts. But knowing about her wasn't enough to write her. I wasn't that great on modern history before starting this project. I did minimal history in school, I got interested later, so I've read intensely about some periods and places, almost all prefaced with "ancient." I started many days with coffee and World War I documentaries. I read up on Dutch colonialism, and that was equally horrific. I read letters of a real Javanese "princess" from the time, so I could get that perspective on what Mata Hari was claiming she was. I read Oscar Wilde's play Salomé because she was obsessed with it. I needed it all to step into her head and that world with confidence. It's mostly invisible, but it matters to make it feel authentic.

The only thing that, well, I don't know if it surprised me, but it really challenged that narrative of her unashamed pursuit of sex. There's a time just after her divorce where she writes in a letter that her husband "left me with a distaste for matters sexual" and the creation of Mata Hari makes more sense knowing that. She came to see her body as her only real asset, so she used it in a way that was safe, she seduced roomfuls of men and gave them her naked body, but no one touched her. She billed it as sacred, as art, and robbed it of much of the lechery.

You present Mata Hari's story as a memoir that was never published. Do you know of any such memoir? Why was it important to you that she speak for herself?

She wrote a memoir but it never made it to her publisher, and it was almost certainly destroyed. I don't know if it ended up in the Seine, but I wondered what kind of a story she'd tell. She never told the truth if it looked bad, and with her life and the circumstances, it all looked bad. So I run with that as it unfolds. It's what she hides by lying that is the key to understanding Mata Hari.

In the first issue we see Monsieur Bouchardon, the prosecutor in her case, calling her a whore, and the audience in the courtroom jeering at her. Why was this an important aspect of her case?

A lot of that part is Bouchardon's own words. The case was flimsy. They had no real evidence of specific acts of espionage; one of the charges was just that she was in Paris during wartime! But it didn't matter. The thinking of the time was that a woman who left her husband and showed off her body was criminally insane and clearly capable of the greatest kinds of evil. Being a spy wasn't about what she did or didn't tell Germany. It was about her moral character. That was enough. She had no chance.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='Distinguishing Fact from Fiction, Working with Karen Berger']

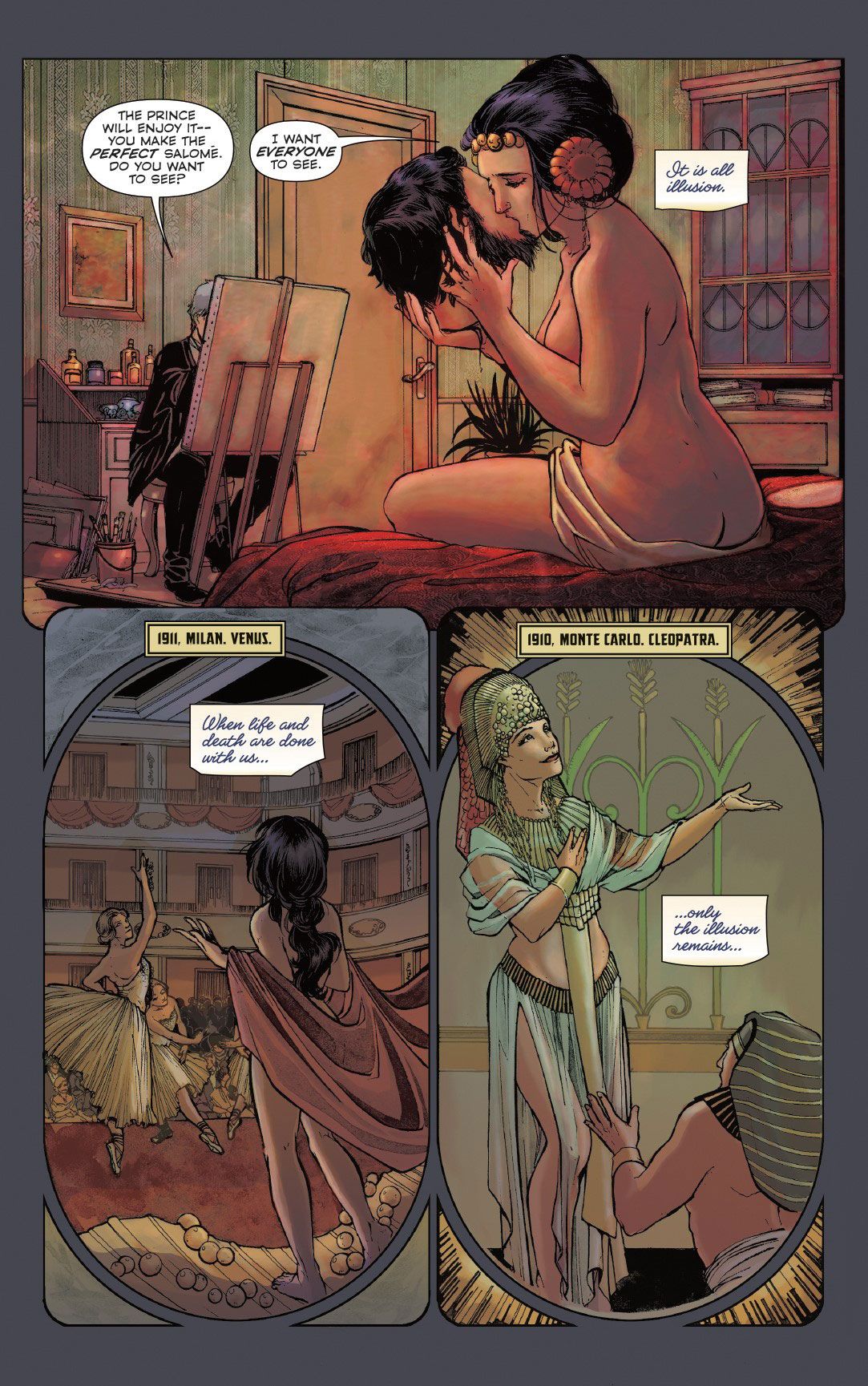

You intersperse the courtroom drama with vignettes of her dancing and appealing to the god Shiva, and you also flash back to her childhood. Why did you choose this way of telling the story rather than a straightforward chronology?

It was the only way that occurred to me to tell it because there were so many parallels and repeating themes in her life. I wanted to put them together. Ultimately, it's showing competing narratives. There's Bouchardon's damning narrative, her romantic memoir, her life events, and the dance. The dance is based on the first dance she did in a Paris Arts Salon that led to her fame, she explains what each veil represents as she casts it off, eventually falling naked before Shiva, all pretensions cast aside and the veils become themes for the episodes as well.

We did an interview back in 2013, when you were the first woman to write a Judge Dredd story, and you were also writing Survival Geeks for 2000AD -- both of those with Gordon Rennie. How has your career progressed since then? What sort of stories do you like to write, and how does Mata Hari fit into your body of work?

Writing Dredd was never an ambition, it was a breakthrough, and I didn't plan that. It led to my writing more for 2000AD, like Judge Anderson, and I'll have a new series with her starting in March.

It led to my working with Gail Simone and other amazing women like Marguerite Bennett and Erica Schultz on Dynamite's Swords of Sorrow series. Then I went to the DC Writers' Workshop in 2016, and they let me team up Catwoman and Wonder Woman. It's been a pretty amazing few years.

Putting it in context, Mata Hari is the thing I've wanted to write since before I even started writing comics. I wasn't ready to do it before. I needed more experience and time. It also feels like the right moment to tell this story, with absolutely the best editor to guide it and artistic team to bring it to life.

How is being a solo writer different, for you, than writing with a partner?

I've always written solo. I started out writing screenplays. I write with Gordon on things we enjoy writing together, and we're writing more Survival Geeks now. I like having another brain in on making stuff up, especially comedy, as it's better to have a person to joke with instead of just a screen.

We do work very differently. He doesn't really plan a lot. I outline every page. We tend to alternate episodes and then redraft each other's scripts.

He'd call it twice the work for half the money. But he's the grumpy one.

How much of Mata Hari is factual and how much is fiction? What facts did you change, and why?

I stick to the main facts of her life, but I can't fit it all in, I have to simplify. Such as, Bouchardon didn't present the case in court, but he might as well have because it was his case: He led the investigation. Where details are not known, fiction is all I can do. It's informed fiction, and most important to me is to try to stay true to who she was, at least as I see her.

In some places, I take a view that her biographies differ on. The biggest one is the alleged affair with her school headmaster, which started when she was around 15 and he was 51. Because of who she became much later in life, it's often assumed it was consensual, that she initiated it. I take the view that she was groomed, that it was an abuse of power; that it was rape. She received all the blame, while he kept his position and reputation. Not an unfamiliar scenario even now, sadly.

Did you create any new characters, or are they all based on real people?

Pretty much everyone is named and real, they often say what they said, they look how they looked; we have their pictures. There's only one character I outright invented, and we meet him later on. He is almost the equivalent of the other Bond girl, you know the one, doesn't get a name, leaves Bond's bed with no further plot purpose and never seen again. Margaretha needed someone to seduce her with La Belle Époque Paris, which in reality took a few years. He takes her to the finest restaurant, performances, and hotel. Then he's gone, having introduced her to the life she wants. This was a typical evening for the woman she later becomes there. It's not too much of a stretch.

RELATED: Racial Drama Incognegro Returns with New Edition, Prequel Miniseries

What sort of responsibility do you feel you have to the characters other than Mata Hari -- are you concerned about presenting them accurately and fairly, or are you regarding them simply as characters in someone else's story?

I'm very concerned with being fair and accurate. I try to use their real words where I can. To only take little jumps, not giant leaps, in my assumptions about them. It would be so easy to turn it into something it's not, the super sexy spy thriller; the female Bond. To fill it with assassins or actually try to turn her into the thing they said she was: the most dangerous spy ever caught. I feel that would do her further injustice.

How has Karen Berger influenced your story? Is she involved in the creative process or strictly afterwards?

People often assume she's just the name on the banner, but Karen is our editor and contact on every aspect of this and every book she's got coming out. She's doing it all.

Karen has been invaluable. I knew the rough structure, I'd written some pages, but she's helped shape it and inspired it to be stronger. We talk through the episodes outline, plans, and scripts, and I'm in on each stage of art from thumbnails on. We all get involved.

Mata Hari #1 is scheduled for release on Feb. 21 from Dark Horse Comics.