News bulletin: The Walking Dead is a friggin' huge deal.

I'm not sure how to measure it, but at least culturally I think the zombie-survival tale by Robert Kirkman, Tony Moore and Charlie Adlard is on track to become the biggest deal to come from indie/creator-owned comics since Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, circa 1988. I think it surpassed Todd McFarlane's Spawn during Season 1. Heck, it might even be giving some corporate-owned properties a run for their money.

Fortunately, we haven't quite hit Christmas special saturation, but there are plenty of items in the AMC Walking Dead shop: action figures and figurines, board games, T-shirts, calendars, posters, costumes, busts, music from the show, a companion book, even dog tags.

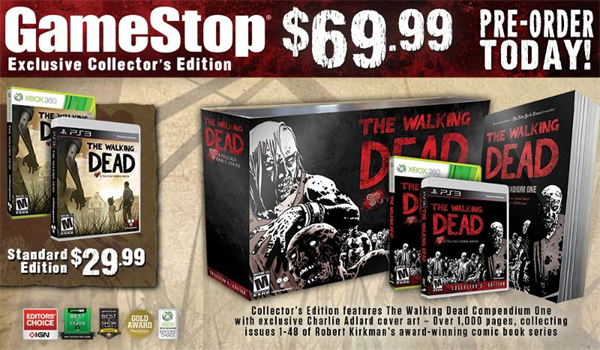

But Kirkman has been doing something with the success of the show that too few comic book adaptations do: He constantly reminds viewers that this hit television drama comes from a comic book. The most recent example is the inclusion of The Walking Dead Compendium One, which collects the first 48 issues of the comic, in the collector's edition of the video game. It also boasts box art by Adlard. That strategy, of visually associating the TV show with the comic, is something Kirkman seems to try to sneak in whenever he can, and it's effective to people who may initially only care about the AMC series. The cover to the special edition of Season 1, the Official Companion Book, and some posters all use imagery from the comic or from comic artists using aesthetics and styles more from the comic than from the adaptation. There have been other strategic connections made: The big zombie obstacle course at Comic-Con International was more about the comic reaching Issue 100 than about the AMC show. And of course there's The Talking Dead, the talk show that follows each episode of the AMC series. Kirkman is often there, and while the focus is on the TV adaptation, he invariably mentions the comic book as the source material. Host Chris Hardwick has also stated that he's read all of the comics. And the Michonne origin story in Playboy definitely received enough press outside of comics circles to reach non-readers. Perhaps most surreal of all, that "Drive to Survive" contest with Hyundai featured Adlard art from the comic book wrapped around the car.

For some this may read as lip service, and sure he could do more. (And some may think it's unnecessary, and I'll get to that in a moment.) But I'm hard pressed to think of a single creator who has used his 15 minutes to try to push attention back to the medium more than Kirkman. I don't know how much he's had to fight to get each of these plugs but from my experiences with Hollywood, I would bet every instance was a headache. Fortunately, it pays off, with The Walking Dead comic collections appearing regularly on the bestseller lists. For instance, the very first volume, originally released in 2004, has become a perennial favorite; it's No. 10 on this week's New York Times graphic novel chart, joined by The Walking Dead Compendium One at No. 3, and Compendium Two at No. 1. Something is directing new readers to the comic.

So, yay, Kirkman. But you might ask, "What about Stan Lee?" Shouldn't he get some credit? I agree he's an amazing public figure who has done a lot to bring comics to Hollywood and, in turn, to public awareness. So, yes, he definitely gets points, but awareness and active participation are two different things. I'm aware knitting is still an active industry thanks to my mother. That doesn't mean I'm buying yarn. Even Lee has admitted he hasn't read a Marvel comic book in years. He might remind people comic books exist, but he doesn't actively point people to them. Kirkman is actively directing people back to his comics, and through his Skybound imprint and his position at Image Comics, to titles by others.

It's an important distinction (and here's where we get to why it's important to do at all). Because as far as comics have come (and we've come far in the last 10 years), they are still primarily seen as a secondary form of entertainment, as stapled storyboards for future movies and TV shows instead of an end product and art form in and of themselves. Imagine if Marvel or DC Comics put a proportionate amount of effort in merging the movies and TV shows with the comics in the public's eye as Kirkman has? Sure, there's the occasional minicomic in a DVD or Blu-Ray box, but nothing on the level Kirkman has been doing. That should change. And yes, that might mean committing the apparent cardinal sin of dipping into one of the immense buckets of money from the movies. But once again, because I know big companies need to be reminder of this: If you like money, it's a good strategy.