Cartoonist Nate Powell is in the middle of a long journey, but that doesn't mean he has no time for short side trips.

As the artist of Top Shelf's award-winning "March" graphic novels detailing Congressman John Lewis' experiences in the Civil Rights movement, Powell recently completed Book 2 of a series that he told CBR will likely expand from a planned trilogy into four volumes of comics history. Meanwhile, he's working on a brand-new original graphic novel called "Cover," as well as a new Dark Horse series with writer Van Jensen.

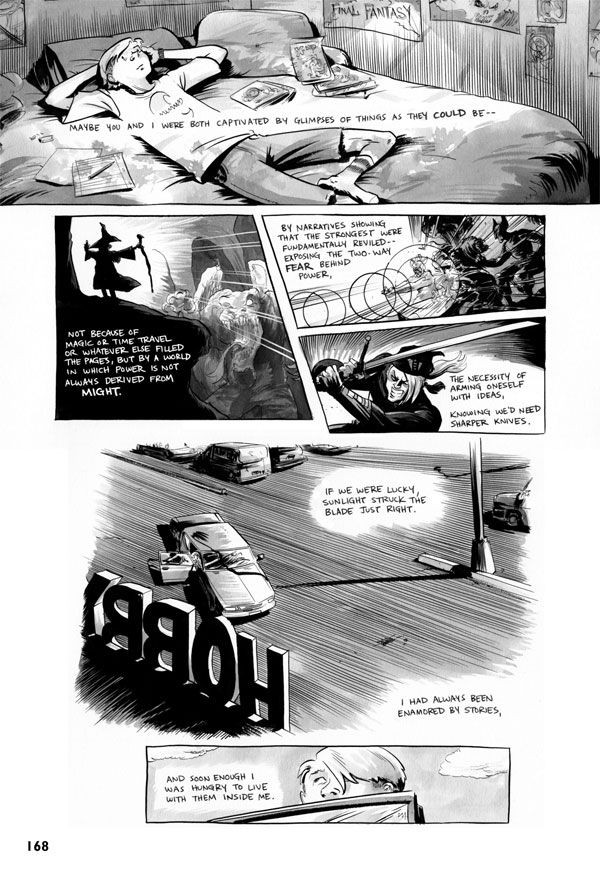

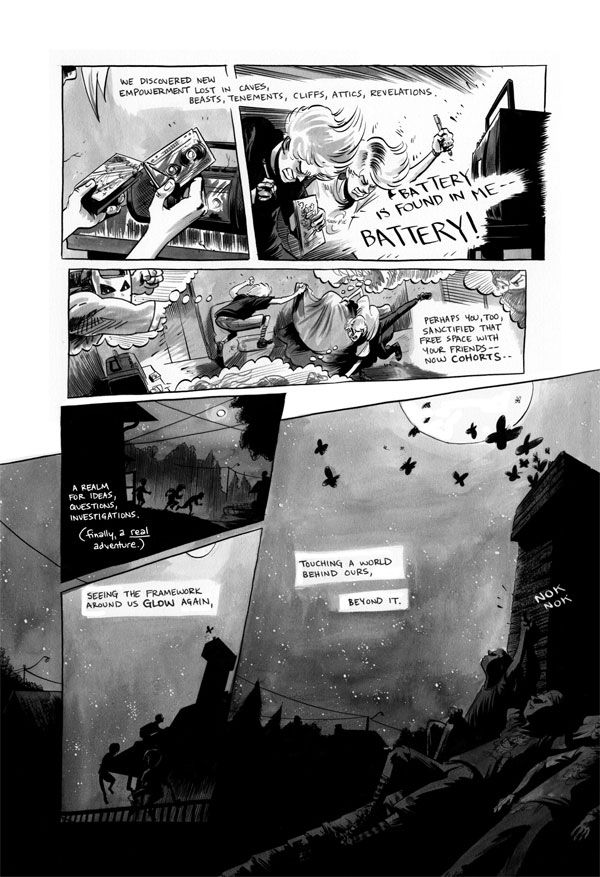

But his next release is a much more personal project. May's one-man anthology "You Don't Say" compiles the cartoonist's short comics from 2004 to 2013, serving as a companion to his previous decade's collection "Sounds of Your Name." While that book assembled his many self-published mini-comics, "You Don't Say" brings together a wide range of essays, short stories and collaborations that Powell created during a time when his career was blowing up in alternative comics circles. The work coincides with his breakout graphic novel "Swallow Me Whole" (a deleted scene from which appears in the new collection) and his follow up "Any Empire." It also includes material from his previous collection "Please Release," the online hit "Cakewalk" and nearly a dozen other short stories and comic essays about music, identity and relationships.

RELATED: Powell Talks Real Life Violence in "March," MLK's "I Have a Dream" Speech & More

In discussing "You Don't Say" with CBR, Powell explained that the book isn't merely a collection of random work but a portrait of his evolution during the period when he set aside his D.I.Y. punk rock roots in order to embrace life as a professional member of the comics community. The wide range of styles and ideas on display in the book not only feed into the massive undertaking that is telling Lewis' story in "March" but also feeds his idiosyncratic creative needs as he continues to move forward in the long path to completing one of the most acclaimed comics projects of the decade.

CBR News: Nate, "You Don't Say" is only your most recent collection of short comics stories. I get the sense that no matter what other big projects you're working on, it's become important to you to not give up on the short form stuff. What does this work offer your creative life? Do you feel you need to do this work as a balance to your longer graphic novels?

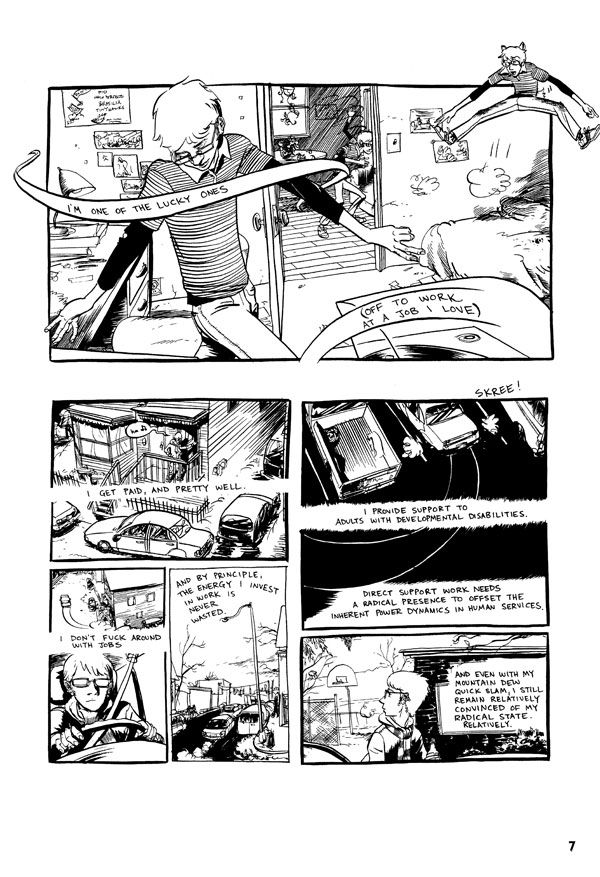

Nate Powell: Yeah, I think that's what it pretty much boils down to. I obviously started my major adult wave of comics by doing these short stories, and a lot of that was because, A) I was in art school at the time, and B) I was 20 years old and impatient. I couldn't fathom doing a story that was 200 pages, then. But once I finished "Swallow Me Whole," I went back to that.

The oldest stories in "You Don't Say" are the ones that make up [my previous short collection] "Please Release," and a lot of that was me trying to change gears in life and to figure something else entirely. But once I had finished "Swallow Me Whole," I did a couple of short stories intentionally to cleanse the pallet, I guess. I was already writing and I think I was already penciling "Any Empire" at that point, but I needed something to give me the sense that it was possible to sit down with something and then two weeks later have something to show for it.

It was so refreshing, and that's especially because the dialogue and feedback that came out of the story "Cakewalk" was exciting and interesting. So then I made it a point that whenever I would finish a major work to take the time of at least a week or two to knock out a short story. I think it's good for my mental health as well as my creative health.

I first came upon your work when I was in college and the bass player of my band kind of shamelessly took some of your art from "Walkie Talkie" and used it on a promotional single we made. So, thanks for that! [Laughter] But I found it interesting, because I started to read your stuff, but I never bought it at a comic shop. Your zines were sold at the record stores in town, and the subject matter dealt a lot with that subculture of young people and music and trying to break out of a small town. Fast forward to today, and I feel like the stories in this new collection reflect a much different time in your life and feature quite a few autobiographical works. Did shifting your career out of that indie rock scene and into the alternative comics culture empower that shift in focus in any way?

More than anything else, once I finished up the stories that made up "Please Release" I kind of stepped outside that area. Really, the stories before "Please Release" that make up "Sounds of Your Name" were all created in a vacuum. I would define those early stories from before 2004 as half-fiction. They were strongly autobiographical, but the narratives themselves were kind of these stitched together fictions. And then I completely turned around and worked through these non-fiction essays of "Please Release" that kind of turned on these aliens inside my brain and inside my voice, I guess. That made me interested in saying different things with fiction and with my made up comic stories.

Really, the way the "You Don't Say" collection works best is seeing it as an entire decade's transition. By the time I had finished "Swallow Me Whole" at the beginning of 2008, I wasn't really going to many [rock] shows anymore. The band that I had been in for 13 years had finally stopped playing music and playing shows. I was starting up one more band, but I was really gearing up for a major transition. I was going to more comic conventions, and I was creatively invested in comics, but I hadn't yet made the jump into comics as a community. I think it was fall of 2008 when I finally realized, "I'm not participating on a personal and emotional level in this yet."

What we're really talking about here is the transition away from punk as a subculture being my identity and my community and then moving into a world in which I'm embracing that comics is my world and my community. By the time the fall of 2008 rolled around -- about halfway through the stories in this book -- I was more or less done with shows and done playing music, but there's always this baggage that goes with underground punk. In retrospect, it has to do with the pretense that the punk subculture or community is the only subculture that can carry some kind of integrity. The idea that it's the only group that can really claim some kind of community. Around that point, I realized that was kind of bullshit. [Laughs]

To put it another way, my wife is one of the most iconoclastic people I've ever met. She has nothing to do with anything. Knowing her has been such an incredible experience. But politically and even aesthetically, she doesn't have much in common with my friends that I grew up around through punk and music. She pointed out at some point that the basis of punk as a culture is its exclusivity. It defines itself by what it isn't. So there was always that thing where I would go to a comic convention -- Emerald City or SPX or MoCCA -- and try to book my convention trip around whatever show would be going on in the area that night. Basically, I would do whatever I could just to not even step into the world of comics personally or emotionally. Then around 2008, I finally made that transition and realized that I'd been a ghost in my life as a cartoonist for years and years. All of a sudden, I was able to let go of my former life and realize what I really was doing. At that point, everything changed.

In a narrative sense, I think what happens with those stories is that I'm finally catching up with my own life. Instead of still writing from a perspective that I'd left behind in life a few years prior, I had all these other doors open for me in terms of my narrative voice.

The style of your line changed a lot over that time, too. Do you feel those two things are connected?

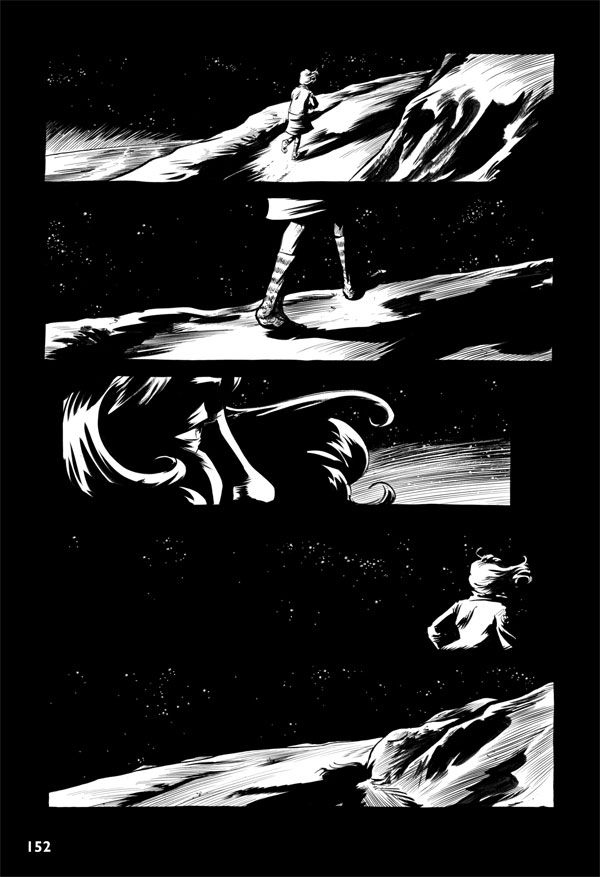

I'd say a lot of it is that. A lot of it is just finally putting 1,000 pages behind you and having a kind of shorthand that changes naturally over time. I think there is a bit of transition that occurred where there was a simplification of my line that happened. It didn't cut out any detail or content, but in between "Swallow Me Whole" and "Any Empire," things got a lot more clear in terms of the division of black and white space.

The last, maybe, ten pages I did for "Swallow Me Whole" had the transition page for my style that I can actually mentally pinpoint. It's one of the pages during the "Baby Ruth" scene that happens in class, when Ruth has her outburst. There was just a way I started drawing the characters where the other students in class started to loosen up and lighten, and it got very 19th century pen-and-ink illustration-y. I thought, "Oh! Why is this getting so clean?" From that point on, I started cutting back from the amount of rendering I was doing, and a few months later I started working on "The Silence of Our Friends" and using these grey washes, and I realized that that's what I was looking for all along. So then when I went back to my flat black and white art, I ended up using less hatching and rendering as a result. A lot of that I think is just a natural transition.

There's a section of "You Don't Say" that is a "deleted scene" from "Swallow Me Whole," and it's presented in the book mostly as rough pencils and lettering without any finished line work. Looking at that, I wondered how much time you spend redrawing pages for a major project. Do you have multiple drafts of each page or work on one board all the way through?

I do a lot of my thinking in the thumbnail stage. Something like "Any Empire" is a 300-page story, but I actually ended up penciling 500 pages for that book. A lot of that, maybe 100 of those extra 200 pages, were penciled, but not super-tightly. They were sequences that I ultimately just redrew completely. Then there were about 100 pages that I just cut, that never made it into the final book.

When I'm doing rough pencils, I like to leave it so that I do most of my thinking during the inks. I can do a penciled page in maybe 20 minutes after it's ruled out. And it feels really nice knowing that after the pencil phase, I can just throw that page out if I need to. Then I can just go out and keep the energy and the dynamism of making the page centered on the final product itself instead of trying to get that in a rough version and then lightboxing it or transferring. I try to avoid as much of that transference of line as possible.

For my newer book that I'm working on now -- "Cover," which is still a few years off -- I'm working on thumbnailing and writing it still, but I've already penciled two versions of the book. I've drawn the first 60 pages of the book, and then I realize it's not time yet. So I just put those pages in a corner, and months will go by, and I say, "It's so much better written now! That means I can start penciling." Then I do another 50 pages and get distracted and think, "It's still not time."

So there's a lot of redrawing. I probably still have 300 or 400 pages of rough pencils for comics that never got finished or have been publishing in different forms.

Aside from the autobiographical essays and some of the newer solo stories, you've got a lot of work in here that are collaborations where you're working off another writer's script. "Cakewalk" you mentioned before which was written by Rachel Bormann who also wrote a story about Carlos Santana you drew for the late, great indie anthology "Papercutter." And there are some other stories from folks you've drawn for in the past scattered throughout. What's the attraction to that kind of collaboration? Is it a similar change of pace to what the short stories offer from your loner work?

Oh, definitely. Back in the late '90s, I did (relatively) a lot more collaboration, though it was much shorter stuff. I did a lot with Emil Heiple, and some of that is in "Sounds of Your Name" along with stuff from other zine writers. But once I started writing and drawing these more long-form graphic novels, I guess that "Cakewalk" and "Bets Are Off" [from a Pretty Girls Make Graves song] were the first time I'd done collaboration in any sense.

But really [the change came from] doing "The Silence of Our Friends" right after that where I was drawing that at the same time as I was writing and drawing "Any Empire." Usually I would ink a page of "Silence" [from Mark Long and Jim Demonakos' script] every morning, and then I'd ink two pages of "Any Empire" in the evening. I did that every day, six days a week. Doing that -- working off someone else scripts and under a certain set of parameters -- very quickly made me pay attention to things that I'd always taken for granted. In a lot of ways, I felt like working with writers -- even on shorter projects -- is like the free school I get to go to for the rest of my life.

Since I finished the stories in "You Don't Say," I've gotten to collaborate with Scott Snyder and also a couple of Italian writers on some short stories, and those experiences have been really satisfying. I think of it as getting to go through an intensive writing program for a few weeks, and I can always bring the lessons back to my own work.

I feel that a lot of your fully-solo work explores ideas about identity or sometimes Southern life amidst this very magical realism kind of tone, but most of your collaborations have been strictly realistic and most often non-fiction. That must give you a set of creative constraints to push up against in a way that breaking the rules of your own narrative reality never does.

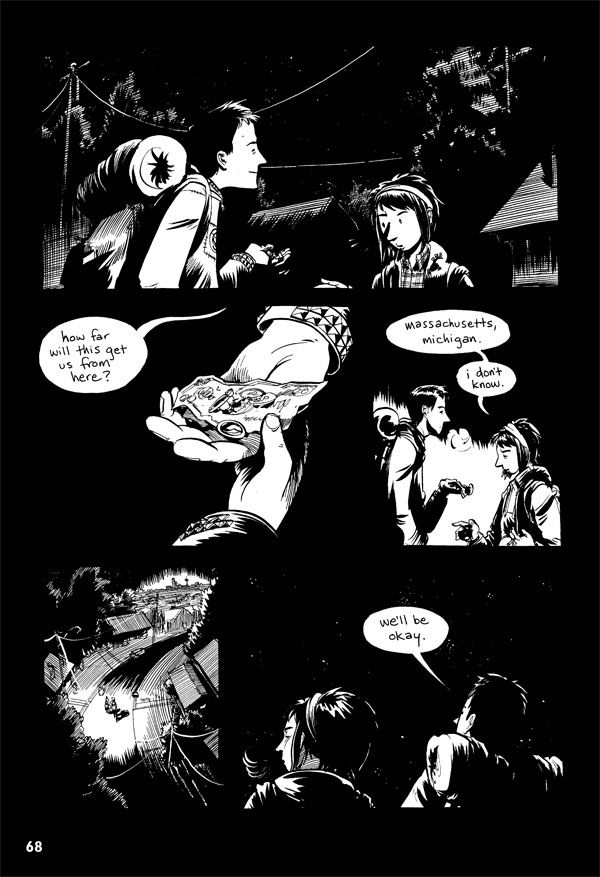

Exactly. That's probably the biggest value to it. Especially when other people's narratives are so nailed down to the floor, as it were, it allows me to read between the lines in their script and see where things weren't clearly defined in the description or the action or the dialogue. I remember with "The Silence of Our Friends," those spaces in between the script revealed themselves to me in an almost Japanese cartooning kind of way. There were moments where I could work in moment-to-moment transitions or try and feel my way with the camera visually around a scene.

There's a moment about three-quarters of the way through "The Silence of Our Friends" where young Mark Long puts gel in his hair, and he hates it, so he goes outside to rinse it out with the hose in his front yard. Then this racist neighbor comes over and vaguely threatens him, and he'd also been punched in the face earlier in the story. So through all this, he's kind of guarding his shame while hosing this gel out of his hair, and everything's turning to spring. Those are the moments I look for in someone else's script -- where I can see moments not clearly indicated in the script that I can also stretch out as much as possible.

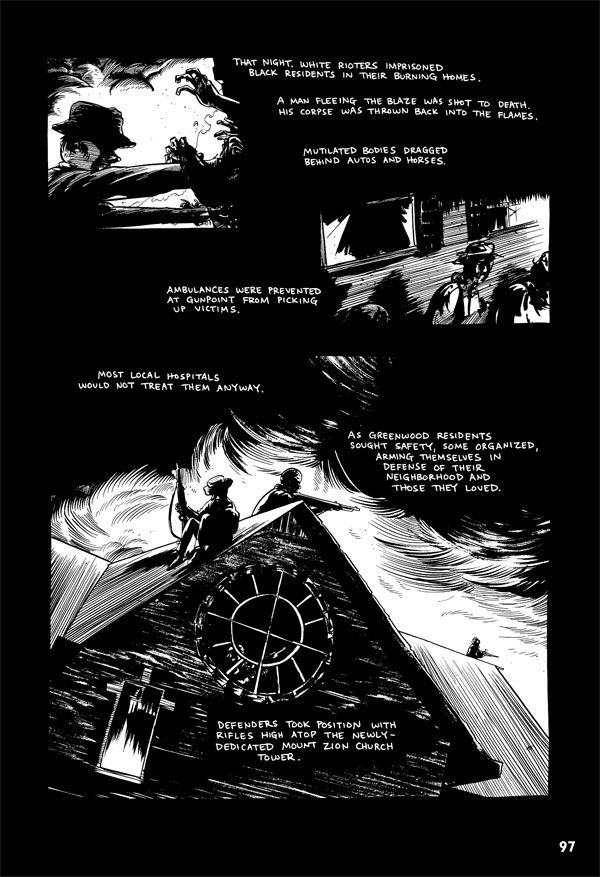

With "March," it's so closely tied to Congressman Lewis' perspective. And in the first book, there's such a vividness and gravity to his experiences and perceptions as a child when he was living on farmland in Alabama. It felt like I had that same kind of lens where I was looking through his eyes as much as I could but also seeing what was happening before him so I could pull the Nate Powelly-ness out wherever possible.

I wanted to ask about your role in "March" in that sense. Just recently, Congressman Lewis and many others returned to Selma to recreate the walk that he took years ago, to commemorate its 50th anniversary. And there was this minor uproar in conservative media because President Obama was there, and the photo his people released of this moment was more zoomed in on his place in the line of people so that you couldn't see that President George W. Bush was also there. There were a lot of sites saying that Obama "cropped Bush out" or whatever, which is crazy because it's not like they doctored a photo to keep him out -- they had a picture taken that wasn't as wide as to get all the people lined up on the bridge.

It was a reminder of how even when we're looking at something that's supposedly an objective moment of history, there are many ways to interpret the facts, visually. That must be a huge part of the challenge you face in drawing things in "March," where there's such iconic imagery connected to those events and thousands of photos. Do you feel the tension in your job between "getting history right" and also presenting what is inherently Congressman Lewis' very personal and subjective memory of those days?

Yeah, it's gotten exponentially more complicated. But in between Book 1 and Book 2 is where I feel like [co-author] Andrew [Aydin], my editor Leigh Walton and I have stepped up to the plate in terms of getting a much more clear idea of what we were needing to get out of the archives. Or even knowing what information we needed to press Congressman Lewis for in terms of details. It's weird, because this is a first-person historical document, and we're trying to follow a lot of the Common Core standards so that we can potentially keep the book in classrooms to be taught as a part of history. But at the same time, it's indisputably a memoir. It's from John Lewis' perspective in the movement, and he tries to be as up front about that as possible. This is his perspective and his memories.

There are many conversations we have about that stuff on a regular basis as we are working through each book. We don't really leave anything out. We've had very few conversations about whether or not something is worth including. In Book 2, there were a couple of sequences where John Lewis had to leave the Freedom Rides for some reason, and then something important would happen -- for example, the bombing of the bus outside Anniston. That was a bus he was supposed to be on, but he left for three days to go interview for a program. Or he was not in Birmingham during the Children's March, because he was working elsewhere, but he was communicating with the Birmingham crew.

So there's a constant series of conversations we're having -- I know Andrew and Leigh are having them literally every day when we're working on the book -- in terms of making sure we're on the correct footing in terms of perspective. Andrew has done an amazingly incredible job of doing his homework. He stays in touch with these figureheads and Civil Rights leaders and other authors and historians. He does a huge amount of researching in addition to working on his craft, which just went off the charts once he dove into Book 2. But it is more than a full-time job to juggle those things in addition to directly working on the books. We really had no idea what we were getting into on that level until after we finished the first book. Then we felt like we knew how we'd all work together, and we had to tighten the machine because it would take twice as much work to make the second book as powerful as we wanted it to be in addition to being tight enough as a work of history.

As an aging punk rocker with two kids and a congressman on speed dial [Powell Laughs], what's it like to revisit work even as far back as 2004 where "You Don't Say" begins? Is there ever a feeling like these are naked baby photos getting put back out into the public eye, or do you just view it as a different part of your career than you're in now?

I really like the naked baby photo analogy. That works perfectly for this, because you're still so tied to it. You know that's you when you're looking at the naked baby photo. You're always going to come to its defense. I feel like, in terms of the work that I published, the only things that are really "embarrassing" are things I don't feel bad about, still. If I look at some of the stories I wrote when I was still in college at SVA, like, stuff from "Walkie Talkie" #1 had a lot of me doing my 21-year-old rants after I took a class in religion and philosophy. It's just so obvious.

But I'd say, inversely, the major feeling I have is that even though I'm ultimately so much happier with the work I've been able to do recently -- strictly speaking, I feel like I've grown as a storyteller -- there is something about working in that absolute vacuum. Sometimes you're not just working without an editor but even without any friends looking over your comics before you draw or send them to the small press printer. There's just a deliberation in work where you have no audience. Even though you're making objectively worse comics, there's a magic to being able to step into a realm that's solely yours when you're drawing your stories.

And I don't want that back. Like, I don't actually want that situation, but I do try to find that cave whenever I draw comics. I've realized that being set free by the work you make is what I'm after. So I'm doing this very regulated, very methodical work in "March," and I'm starting on this series I'm doing with Van Jensen at Dark Horse. But working on this book, "Cover," is where I get to return to the womb, as it were, and not really have a tight publishing schedule to finish the book on. It makes you recognize that the feeling you're going after is one of sitting alone in your room with a story. That's what I miss.

Considering the fact that you're looking down a two or three-year stretch where all your big work is already on track and set in place for you, do you think that you'll find time to do more short stories like we're seeing in "You Don't Say," or does "Cover" replace that kind of work for you moving forward?

The shorter work is built into my schedule. I have a few more short stories planned that I absolutely want to do. It's just a matter of really playing it cool. When I finish "March Book 3," I have a story I want to do that I actually thumbnailed before I worked on Book 2, I think. I just didn't have time to finish it. It was going to be in "You Don't Say," but I'll get to it, and a few others I'm working on.

But there's such a difference between doing the graphic novels that are mine, and then the short form comics. In a punk context, I still need to record a seven-inch or make a demo tape really fast, sometimes. There's a satisfaction in projects like that. Time is so much different now, not only as a dad, but also being 36. Sometimes it's ridiculous to me to think that when "March" is all done as a saga -- it'll probably be four books now, because we're planning a super-long epilogue that will probably fit a fourth book -- that'll be a total of seven years I've spent drawing that. But now I'm halfway through it, and going, "Oh, okay. I've got three years done." That was unfathomable when I started, to think that I'd go so quickly through three years of my life. And it's kind of liberating, too. I'm an American cartoonist, and I'm going to draw until I die at my drawing table. I mean, it's not like there's an awesome retirement plan for this job. [Laughs] So that really takes the pressure off. Do what you do well and what you love doing -- and I've got about 50 years left to crank some stories out.

"You Don't Say" arrives this May from Top Shelf.