Manhua are comics that originate from China -- like Korean comics or manwha -- they often fight to establish a culturally unique identity and struggle with the often overpowering influence of Japanese comics. Many Korean comics have succeeded here in the U.S. but very few Chinese comics are even publishedhere (I know of a few here and there ....they certainly exist, I believe Dr Master publishes a few series but if I'm mistaken about the scarcity ofChinese comicsin English please speak up!)

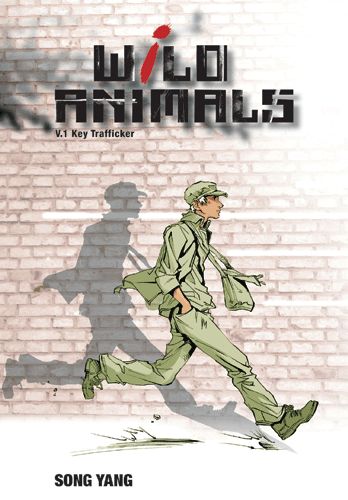

Wild Animals is an adaptation of both a novel and a film about a teenager's experience during the Chinese Cultural Revolution and has just recently been published by Yen Press in English.

Wild Animals is an attempt to createa comic that is Chinese in both subject matter and in artistic style according tocreator Song Yang andthe result is something that is visually accessible but content-wise feels asthough anyone not born with certainChineseexperiences and types of knowledge will miss quite a bit of intended meaning.

First, let's get the art out of the way. It is very unusual mix of what I would call "photorealism" and more traditional seinen-style representation of figures and environments. I call this mix "unusual" because unlike folks like Ai Yazawa and Miki Aihara who use adapted photographs of Tokyo as backgrounds in their manga, here Yang has chosen to use photorealism to represent portrait-like close-ups of a woman -- the woman, if you know what I mean-- of our protagonists daydreams and desires. This was....odd. In general the art is serviceable, but the artist still has a lot to learn I think. His action scenes are generally incomprehensible, although his close-ups (often more like "portraits" as I've mentioned before) are engaging. However a comic isn't comprised simply through stringing together close-ups and action scenes -- something as to make it flow and that is really what Wild Animals seems to lack artistically.

I've dealt with the art first, because I have a certain frame of reference to compare it to (Japanese and Korean Comics) but it is thesubject of the comicthat purposefullyplacesit outside my cultural orbit. I, and really anyone who isn't Chinese, isn't the intended reader for this comic.The creator even makes a point of saying so in the forward: "to create something unique to China['s culture]," an art form that needs to "completelyunderstand and integrate elements ofChineseculture." Reading was frustrating because I felt as though I had no entry point to theexperiences of the main character Ma Xiaojun since I really have no entrypoint to the CulturalRevolution as a real lived experience or even simply as a historically remembered nightmare. Throughout the comic we see him struggle to try to do something incredibly normal for a teenage boy -- get close to the girl. But for him and his culture this is practically a taboo act, and it is the stress ofliving with this taboothat leads him to do something absolutely horrific in the closing page in the comic (this horrific act is only referenced, we'll find out more in volume 2 what really happened).

In a way, the spirit of this comic is almost exactly the opposite of Persepolis. Persepolis really does an extraordinary job of conveying multiple worldviews and cultures that often clash but can also converge,but there is a maturity that comes with being able to tell a story that can appeal to multiple cultures. Yang, concerned with creating something that resonates for the Chinese reader, certainly wasn't thinking about thepotential Western one as well. I don't think that is a bad thing but it does make one wonder if this book wasbest choice to represent Chinese comicsinternationally at this particular point in time.

Review Copy provided by Yen Press