The artwork in Elaine M. Will's Look Straight Ahead, a webcomic now available in print, is uniformly excellent. Striking the perfect balance between cartooning and representational art, she's built a comic book world that's recognizable as our own, but as drawn by her, and then she's filled it with realistic characters delineated in a personal style.

As accomplished as the artwork is and as well as it succeeds in all the various categories comics art can be judged by — design, storytelling, character acting — some of it seems truer than other parts, and it's these elements that make Look Straight Ahead a truly exceptional work.

The story is a fairly straightforward one. Quiet social outcast Jeremy Knowles is having a pretty rough time at his private school: He has a few friends, and is a talented artist, but he's regularly bullied; he's so shy he can't even speak to the girl of his dreams (who's dating one of his friends), he feels alienated from his well-meaning but clueless parents and, compounding everything, he can't sleep.

One day at school he seemingly snaps, smashing glass beakers in the lab and storming out. Then he has a vision in which he thinks God, in the form of an Eastern dragon, is communicating with him. That night, his father finds him furiously digging in the backyard, convinced that one of the bullies from school has secretly planted a bomb there to kill him.

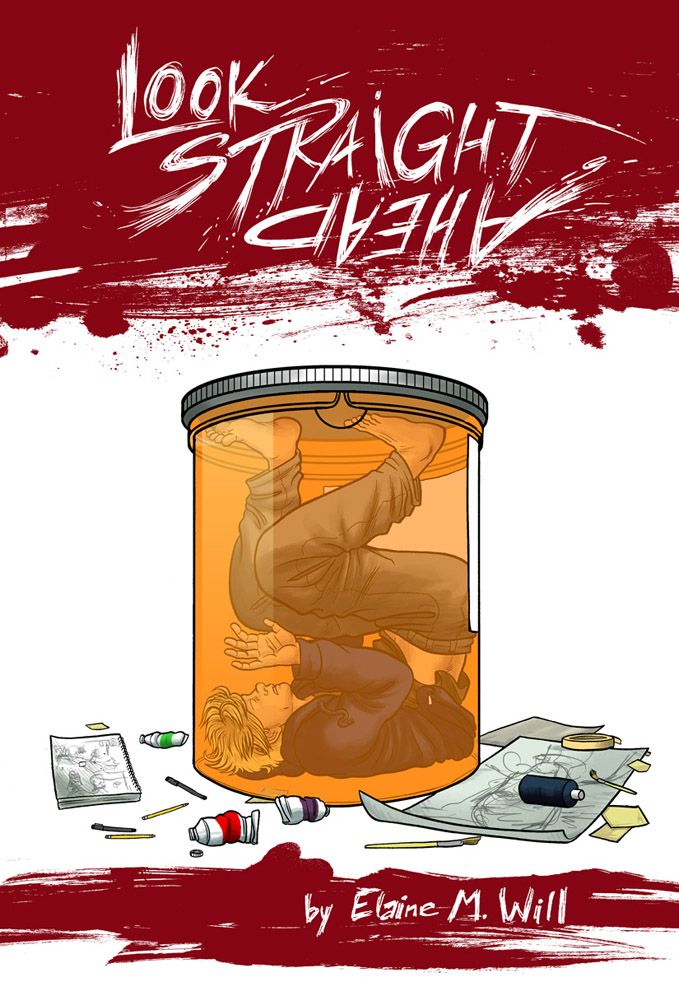

Jeremy is suffering from some form of mental illness, and the rest of the book details his struggle, in and out and in and out of an institution, and on and off and on drugs.

Because Jeremy is an artist and this is a comic book, Will is able to use her art, as filtered through her character's art, to express Jeremy's state of mind, and it is very much the art of a frustrated, alienated teenager. There's a great deal of imagery that I would call cliched, and some of the symbolism employed over-obvious, but then, this is a teenager we're talking about, right?

And thus the imagery looks like what one might find in the notebook of a young person sketching alone in the corner of an all-night diner, or in the edges of handouts and notebooks at school, or hidden away in a box of a talented adult artist who is embarrassed by the work he or she might have made when they were young, but can't bring themselves to throw it away.

There are lots of incredibly, ornate squiggly lines, panes of geometric shapes, puzzle pieces and monsters. Jeremy's illness takes on personification as a devil character, and he's drawn as a man in a nice suit with a gargoyle's head. Several scenes take place in what look like those Ditko-esque realms Dr. Strange hangs out in. At one point of crisis, Jeremy draws himself a sword and slays the dragon of his illness (which Will draws as a skeletal pterosaur of some kind). At certain points, the black-and-white art gives way to brilliant color.

There are certainly more accomplished effects as well, with people's faces becoming whirlpools, or the sidewalk reaching out amorphous tendrils with figures and faces to absorb Jeremy and so on.

The art is, in a word, trippy, but it's trippy in both the way a teenager might use that word and the way an adult might use that word, which is pretty damn impressive, really.

Mental illness is a terrible thing for anyone to have to deal with, but it can be particularly difficult for teenagers, who don't really have the life experiences to know what might be happening to them, what's normal versus what's natural but requiring medical attention.

It's even more difficult for someone with a religious background, in some cases, and more difficult still if that teenager with a religious background is also an artist of some kind, as there are additional fears of not wanting to go against what might be God's will, and not wanting to dull the creative part of you. In other words, it's always hard to tell where a mental illness ends and the where the person suffering from it begins.

That's Jeremy's main struggle in Look Straight Ahead, and it's one communicated in a way that mere words can't really manage — personalized imagery and iconography, tweaks and alterations to comic book storytelling conventions.

It's a pretty important story, and it's told in such a way that it communicates the confusion and horror of mental illness the most effective way possible: Letting a reader see exactly what it's like, without the reader actually having to suffer through it themselves.