The first six pages of Beautiful Darkness comprise one of the more dramatic sequences you're likely to see in any comics work. On the first, a saucer-eyed young blonde is having hot chocolate and cake with the fancily dressed man she met at the ball, and then something is falling from the ceiling — "But this isn't how things were supposed to turn out!" — and after a quick, desperate struggle, the reader is treated to maybe the last thing he or she might expect to see. It's creepy, scary and intriguing, a potent dare to stop reading, and an irresistible lure to turn the page.

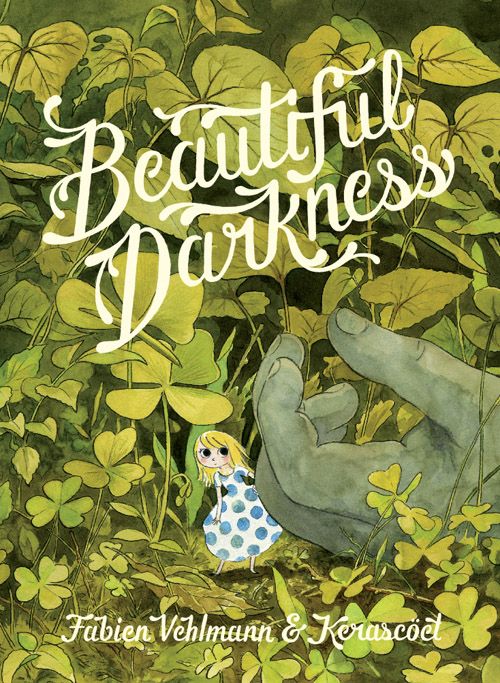

The book is a collaboration between writer Fabien Vehlmann, who wrote the quirky, Jason-drawn comedy Isle of 100,000 Graves, and Marie Pommepuy, one-half of the art team known as Kerascoët, who drew the Miss Don't Touch Me books, and who rather lavishly renders this story. Publisher Drawn and Quarterly bills it as an anti-fairy tale, but adding "anti-" seems a bit much, given how closely elements echo fairy tales and more modern, but still classic, children's literature: Thumbelina and Tom Thumb, most especially, with at least a touch of Hansel and Gretel near the ending. There's some Beatrix Potter in here, particularly in the visuals, and anyone who has read or encountered any adaptation of the The Borrowers will find much of that as well.

Without ruining the fairly shocking opening (any more than perhaps I already have by saying it's shocking), the saucer-eyed blonde is Aurora, the principal character among a society of tiny people. They range rather dramatically in size, shape and design, but all are small: The littlest are about the size of a pea, while the largest looks like a living baby doll but is still small enough to fit comfortably in the palm of a child's hand.

All are drawn in a very loose, very cartoony style, in sharp contrast to the natural world around them, which the artists draw in a realistic style with beautiful detail, all beautifully water-colored. The tiny people have quite suddenly lost their unusual home, and are stranded somewhere in the woods, beset by dangers on all sides: insects, birds, frogs and small mammals, the occasional footfall of a human, and the threat of starvation.

And, as always, nothing is so dangerous to people as other people, not matter how teensy they may be. Aurora struggles valiantly to keep her kind fed, alive and in comfort, trying to forge alliances with the animals, but animals will be animals, and people will be people. Soon jealousy, selfishness, spite, deception, greed and cowardice begin to tear the little people apart, and things get worse and worse for our little heroine. Her peers are all capable of shocking cruelty, ranging from cannibalism to animal mutilation, but there's a disturbing child-like naivety to much of it -- as if they're playing games without realizing limbs can't be reattached and the dead don't come back to life.

Before long, it's The Borrowers meets Lord of the Flies.

There's an "it" to be gotten, but there's probably more than one interpretation of what that "it" is, exactly, that an argument could be made to support. And even if taken completely literally, the book still works. The origins of the little people might seem a bit more bonkers that way, but the narrative they're embedded in still works just fine as a series of beautifully crafted jet-black gags in which a variety of horrors fall upon teensy cartoon people in the woods until they gradually destroy themselves.