Here are five words that, to my knowledge, have never been spoken or written in this particular order: "I don't like Kate Beaton."

This being the Internet, there very well may be someone somewhere who does not, in fact, care for Beaton's work, but I've never run across that person. Similarly, it's difficult to find a cartoonist whose work is so widely enjoyed and championed that affection for it approaches universal.

From her long-running online comics about historical and literary figures (collected in the Hark! A Vagrant books, a second volume of which is due soon) to her online-only, more-doodled-than-drawn strips about visiting her family, Beaton's work is always engaging and easy to share.

A classic cartoonist, hers is a style that succeeds in looking effortless while remaining highly detailed enough to convey various time periods and settings. And this week, we finally get to see her style and storytelling sensibility applied to a new medium: the children's picture book, beginning with The Princess and the Pony.

Now, while it's new territory for Beaton, picture books are obviously neighbors of comics, and the border they share is porous and unguarded. Both rely on a combination of words and pictures, just in different ratios. In many children's picture books, this one included, if you regard pages as panel borders, or implied borders around distinct drawings, the only real difference is the narration doesn't appear in boxes, and the dialogue in quotes rather than bubbles.

I've always been fascinated by the similarities and differences between picture books and comics, and have often found the greatest one usually involve the presentation more than the contents themselves.

For Beaton's many fans, this presentation affords some new opportunities for how they engage her work. First, here's a relatively rare chance to read it not online, but on paper, and on paper first. Second, it's an opportunity to see her art bigger and brighter than ever before, as the pages are about 9 inches by 10.25 inches, and seemingly fully painted. She makes great use of all that space, filling many of the panels with rich backgrounds, alive with little gags to look for.

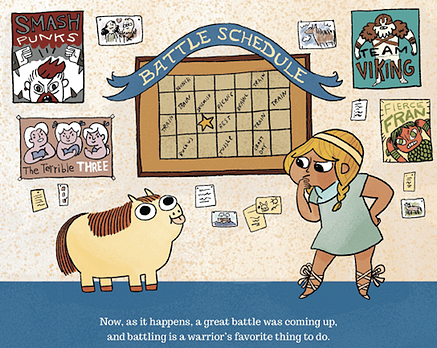

The princess of the title is Princess Pinecone, the smallest warrior in a kingdom of warriors, who was excitedly looking forward to her birthday. Warriors tend to get "fantastic birthday presents," Beaton's simple, direct narration tells us. "Shields, amulets, hemlets with horns on them. Things to win battles with."

Pinecone tends to get a lot of cozy sweaters with sayings and pictures on them. Appropriate gifts for some little girls, maybe, but not little warrior girls. On this particular birthday, she campaigns hard for a very particular present: a big, strong, fast warhorse.

What she receives instead is the round, little, flatulent, curtain-chewing pony you see on the cover. That pony, by the way, seems to be one character who originated in Beaton's online body of work. I scoured the crowd scenes for familiar faces, but the only one I recognize is that pony, which has made several appearances in Beaton's comics. Well, maybe not that particular pony, but certainly bug-eyed, blank-faced, stubby-legged round ponies of its sort, anyway (uust check out the "pony" category of her archives).

With a big battle coming up, Princess Pinecone attempts to train her new pony for the event – which is more sporting event than actual battle, complete with bleachers, snacks and big foam hands for spectators – but it doesn't look good for the pair.

But perhaps cuteness can be a weapon, and maybe even the most powerful one of all?

The Princess and the Pony makes the expected reversal, along with a last page callback to an earlier gag to deflate any sense of over-seriousness, but these moments are predictable only in their contribution to the structural integrity of a picture book, not their exact content. Also, if you're a little kid reading or being read this story, then this is likely one of your first dozen or three books, and thus you're not going to pay as much attention to the craft as you are to the jokes.

Beyond offering Beaton's followers a new place to see new aspects of her work, the move to a medium with a very young audience means The Princess and the Pony will likely earn her many new fans. I wouldn't expect any of them to ever utter "I don't like Kate Beaton" either; this is a confident, accomplished work that is all-ages in the literal definition of that term.

If Beaton decides to focus on children's picture books, it's easy to imagine her fitting in quite well with the likes of Mo Willems and Jon Klassen and similar writer/artists with a knack for fun stories that are as much for the parents who read them as they are for the kids being read them.