Director John Erick Dowdle and his co-writer/producer brother Drew Dowdle -- the team behind The Poughkeepsie Tapes, Quarantine and Devil -- return to their found-footage roots with the supernatural thriller As Above, So Below.

Opening today nationwide from Legendary Pictures, the film follows a team of American explorers searching for the fabled Philosopher’s Stone in the Catacombs of Paris, the city’s historic subterranean cemetery. However, as they descend deeper into the winding maze of tunnels, they are haunted by terrifying visions that threaten to consume them.

The Dowdles spoke to Spinoff Online about the terrors of enclosed spaces, the challenges of filming in catacombs, and the different levels of hell.

Spinoff Online: Your last film, Devil, was supernatural and psychological. How did you go about capturing both elements again?

John: We took more of a mythical approach; there is a little more mysticism and occult stuff. Devil was supernatural, but it was lightly so. There were supernatural elements, but you don’t really see too much.

Drew: We always wanted to do something more supernatural in the documentary/found-footage style.

The catacombs are an essential character in the movie. Did you conceive the premise and then go secure the rights to film on location, under Paris’ streets, or vice versa?

John: It’s sort of a combination of things. We had this idea that we wanted to do a female Indiana Jones character. Drew and I had a long fascination with the Parisian Catacombs, but we hadn’t put the two ideas together. Thomas Tull, the head at Legendary, called us one day and said, “Hey guys, I’d love to do something with the Parisian Catacombs. Do you have any ideas?” It was that lightning-bolt moment: “Oh, my God. We could use this character Scarlet in that journey. It would be the perfect match.” We came in and pitched that. They bought it on the spot. When we went to Paris, we were deep in prep, even before we had permission to shoot in the catacombs. It was only the day before shooting that we were actually granted permission.

Drew: We gambled a little bit. We were very much all-in on that specific location. We were fully crewed up and prepping in Paris. We had a couple of sections of catacombs that we had permits for, but a couple of the key ones, we didn’t get until the day before shooting. We were definitely playing chicken a little bit.

CBR TV: Dowdle Brothers Discuss Their Horror Film "As Above, So Below"

Was there a Plan B if they said no?

John: No, we don’t believe in Plan B [laughter]. That’s sort of our mantra: There is no Plan B. We just have to figure it out.

This isn’t a set. You are shooting in this maze of tunnels, in the dark, and everyone is crammed in there with the equipment. How claustrophobic did it get for the cast and crew?

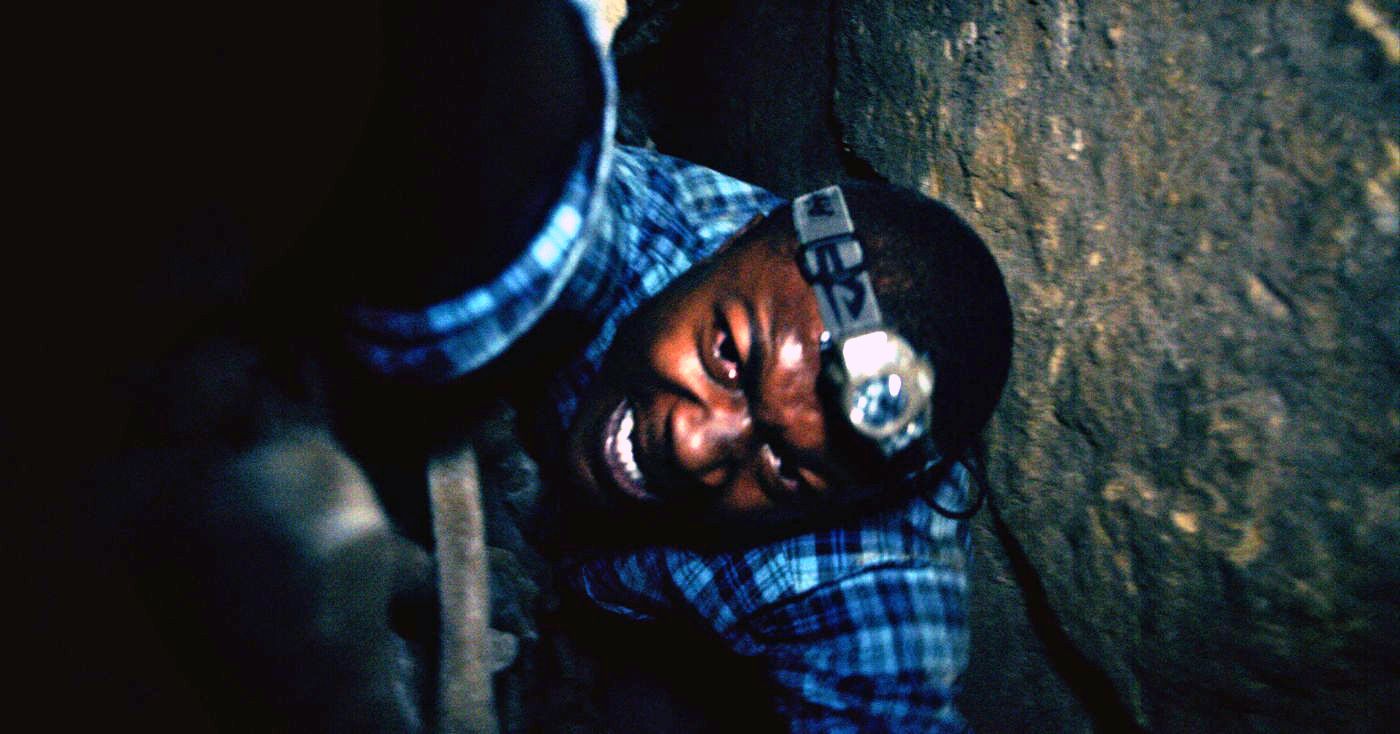

John: Incredibly. We did what we’re calling a “camera wardrobe test.” Before shooting the scene, we asked, “Is anyone genuinely claustrophobic?” We realized Edwin Hodge, who plays the cameraman, actually is claustrophobic. He plays claustrophobic in the movie, so it really enhances the performance. You really feel his terror.

It was tight. We had to stay minimal crew. We lit the whole movie using the actors’ headlamps. We weren’t supplementing that light. We had to do this really guerilla. There wasn’t much space down there.

Drew: Whenever we were shooting a scene, we only had the cast and three or four crew members total. We would have a base camp 30 feet away, wherever there was room to put more bodies. We were stacked on top of each other.

What about confined spaces speak to you as directors and writers?

John: We love doing films of crisis. Whenever a crisis erupts, it triggers that fight-or-flight response. We find confined spaces take out the ability for flight. Once flight is taken out of the equation, it forces characters to hit their fears head on and face the things they would normally try to get away from. That’s an interesting experiment to do. If the characters can’t escape this, how can they deal with it? That amplifies tension. Confined spaces, or having a tight timeline, both of those things enhance the inherent energy a movie can have.

Why don’t they get the hell out of there?

John: Their exit collapses. We always believe characters should be smart. “What would I do in the situation? Don’t drop the knife in front of the killer. If you can get out, and it’s life-threatening, get the hell out. Abandon mission.” Growing up, our dad used to call Drew, “Mr. Exactly.” Drew will not go for anything illogical. He keeps me honest.

Drew: It was important in this script to make sure that nothing too life-threatening happened before the way we came in became sealed. Nothing too dangerous could happen up until that point because that is one of those moments that drive me crazy in movies. “You would leave. You would go. You would do that.” We made it clear that they get into the meat of it after the way they came in is no longer an option. Finding a new way out is very difficult down there. That’s part of the reason they need to keep going deeper, is to essentially look for a way out.

As far as plot is concerned, what are some of the initial signs that something is wrong?

John: There’s a choir down there doing this strange tonal music. They do come across a tunnel full of bones, which actually exists down there. Soon they feel the maps and the tunnels aren’t quite matching up.

Drew: It’s a very strange place in real life. When you’re down there, we really wanted to toy with, “Is this just weird or is this supernaturally weird?” That’s a fun area to play in.

Do you explain why the characters are experiencing their personal demons, or is it just a form of mental torture?

John: One of the references we used putting this together was Dante’s Inferno and the levels of hell. One level is the adulterers and they have a very specific kind of torture implemented. We borrowed from that, but we don’t go into a lot of explanation. We tried to treat it as if you were there, how would you see this? You wouldn’t get the full story. You couldn’t get the flashback to the character as a child. We wanted to keep it in the present time and not do a whole bunch of explaining, but you can get the gist of what each person’s backstory is.

Drew: With some characters, we go a little bit further in terms of exactly what you learn. But, we like the idea of a couple of characters seeing an image and not knowing more than that and begging the question of, “What is that? What was it that they did?”

Quarantine and Devil played up the scares with sound and off-camera kills. Are you continuing down that route or is this more in your face?

John: Part of the reason found footage, or the documentary style, is such an effective way to do horror films is you don’t feel you have to see everything. We don’t feel every kill, every monster or every zombie has to be right in your face.

When you see just a part of something, somehow that makes sense. Part of it is giving the audience enough that you trigger their imagination. We realized in Quarantine that when you see the zombie-ish people for a second, it’s really scary. You see them for three seconds and it becomes silly. The audience’s imagination can do a better job of anything you can do. If you can just trigger that imagination and let it run, that will make it scarier.

Drew: This was such a great setting for sound design, too. That was clear from the first location we did. That element of the movie is so critical to the scares because sound moves in interesting ways down here.

After producing projects that are PG-13 and R, which class rating works best for you?

John: This is R, and we love R-rated. I remember in Devil, deep in post, we would get it kicked back to us with, “It’s rated R because it’s too intense.” “Too intense? That’s the point of the movie.” They would be like, “You have to bring down the intensity.” “What does that mean? You mean make the movie less good?”

Early on with Legendary, in one of our first meetings, we said, “We really think this should be an R-rated movie. We personally like the found-footage movies or horror films that are R-rated. They always feel like they are more interesting and good.” To their credit, they were like, “Sounds great.”

Drew: When you are dancing around language and blood in a found-footage movie, it’s amazing. In Devil, we had a sound effect kick back over a black screen. All the lights were out and they said the sound effect was too wet. We said, “Let’s try and never make another PG-13 movie again.”

John: Then you can take the gloves off and make an exciting, intense experience for the audience without trying to rein yourself in.