If there is any true visionary in comics today, surely it is Jim Woodring. No one is able to plumb the horror and wonder of simply being alive in the same surreal and enigmatic fashion as Woodring, nor able to combine veer from whimsy to Lynchian terror at the drop of a hat. In graphic novels like Weathercraft and Congress of the Animals, he has shown himself to be not only a (wordless) storyteller of the highest order, but one whose stories feel both warmly familiar and totally alien at the same time -- no small feat.

Woodring's latest book is Problematic, from Fantagraphics, a collection of sketchbook drawings made between 2004 and 2012 on a series of pocket-sized Moleskine books. Ranging from concept sketches to figure studies to caricatures to the sort of phantasmagorical creatures that populate his universes, Problematic is both a stroll through Woodring's unique imagination and an opportunity to see his working process -- to see the "idea batteries" (as the press release calls it) up close and personal.

Woodring was kind enough to answer a barrage of questions I threw at him about Problematic, as well as his next, upcoming graphic novel Fran, a sequel to Congress of the Animals. I could have spent weeks pestering him with questions, and I'm grateful for taking the time to respond.

Robot 6: Before we discuss Problematic, I'd like to ask you about Fran, your next graphic novel scheduled to come out in 2013. Can you talk a little about the plot of Fran? Does this new book give you the opportunity to explore and/or learn about Fran's character a bit or is she fully formed in your mind?

Jim Woodring: Fran is without a doubt the most complex and difficult story I've ever worked on. When I told my wife and son the plot, they were dismayed and begged me not to do it ... so I knew I was on the right track. It's a somewhat traumatic story.

The introduction of Fran in Congress of the Animals was a real game-changer for your Unifactor set of stories. You come to the end of it realizing Frank and his world has changed significantly. What made you decide to go this route? Was it a conscious decision on your part to introduce Fran? Did you feel the need to shake things up at all and introduce a new character?

When the idea of bringing Fran into Frank's life occurred to me I thought it was a great notion and watched complacently as the story of Congress of the Animals unfolded. Then I realized her being there changed everything because Frank's primary relationship had been with the Unifactor, which was always calling him to come and find out something. With the acquisition of a mate, Frank would either lose his wanderlust or go on adventures with her. Both possibilities seemed to spell death to the driving force of the whole enterprise. As things worked out, that's not the case but the road away from that undesirable result is somewhat brutal.

Moving on to Problematic: Not every cartoonist or artist keeps a sketchbook. What made you decide to start sketching?

Well, when I was an adolescent I read Delacroix's daunting assertion that an artist should be able to sketch a man falling from a high window before he hits the ground. That statement roused me in a major manner. I loved the implication that an artist could attain almost superhuman skill, and I also loved that he had chosen such a morbid example of a rapidly moving subject. At that time everything I wanted to draw was gruesome, weird or scary and I was excited to think that as an adult artist I could maintain my interest in such grim stuff. Then I saw David's sketch of Marie Antoinette on her way to the guillotine. Knowing that he was right there, watching that historic journey and capturing something of it on paper (and knowing that Marie was about to have her head chopped off) made that nothing little drawing deeply interesting to me and awakened me to sketching's potential.

Also around that time I saw Rembrandt's sketch for his painting The Return of the Prodigal Son alongside the painting itself and was struck by how much energy and personality the sketch had compared to the painting and also compared to his more finished drawings and etchings. I wanted to be able to do something like that ... so I made my first attempts at keeping a sketchbook in junior high school. It was the beginning of my self-identification as an artist, which, having nothing else at all going on I could be proud of, I clung to like a delusion.

Do you find keeping a sketchbook helps generate ideas for future stories? Or is it more a way for you to improve your art? Both? Neither?

The books themselves don't help me do anything ... drawing in them isn't easier or more stimulating than drawing on scrap paper. But having a pocket sketchbook on me at all times means fleeting impressions and ideas that might otherwise be lost are captured. I fill up a minimum of one sketchbook per month, which requires me to draw in them even when I don't feel like it. This extra drawing practice is no doubt beneficial.

In the introduction to Problematic, you write about how the pocket-sized Moleskins were the "answer to your prayers." Can you talk a little bit about why these particular sketchbooks proved to be effective in encouraging you to draw where others did not?

As a kid I used to see little sketchbooks that were very similar to the Moleskines in old-fashioned stationery stores, but by the time I got around to wanting to buy one they had vanished along with ink knives, two-for-a-dime nibs and half-pound sticks of sealing wax. I tried to find little sketchbooks like that for decades. The closest I could find were little memorandum books, but they had thin, lined paper.

I had a hard time keeping a bigger size of sketchbook, especially after I saw some of the immaculate sketchbooks that some artists keep. I tried to do the same and I just couldn't. There were always drawings I hated so much I would inevitably ruin the books trying to correct, cover or remove them. I wanted a pristine sketchbook and couldn't stand what messes I made of them. For some reason that didn't bother me with the little books. The same sloppiness and chaos that I couldn't abide in the big sketchbooks I found pleasing in the pocket-sized ones.

How did you go about selecting material for Problematic? Did you have any difficulty deciding what to include or leave out?

For Problematic I went through about thirty sketchbooks and picked out things that I thought had that peculiar glow that indicates a link to something hidden and powerful. Some of the most intense (for me anyway) are the most simple, like the drawings labeled SALVIA DIVINORUM. My favorite function of art is fetish-making, creating an object or drawing and then turning to it for answers, contemplating it and finding your contemplation rewarded ... that is for me is the whole game.

One of the recurring images in the book is of the warped faces, where you've drawn an abstract shape and then tried to draw a face or person in the shape. What do challenges/games like these provide for you? Is there a motive beyond simply twisting the human form?

Actually those things are slightly upsetting for me to do. I almost feel like I'm mutilating someone, but I also feel it has to be done if I'm going to prove to myself that I'm not afraid of certain things which in truth I would rather not see. Also it's fun to see how badly you can distort the shape of a head and still have it read as a personality.

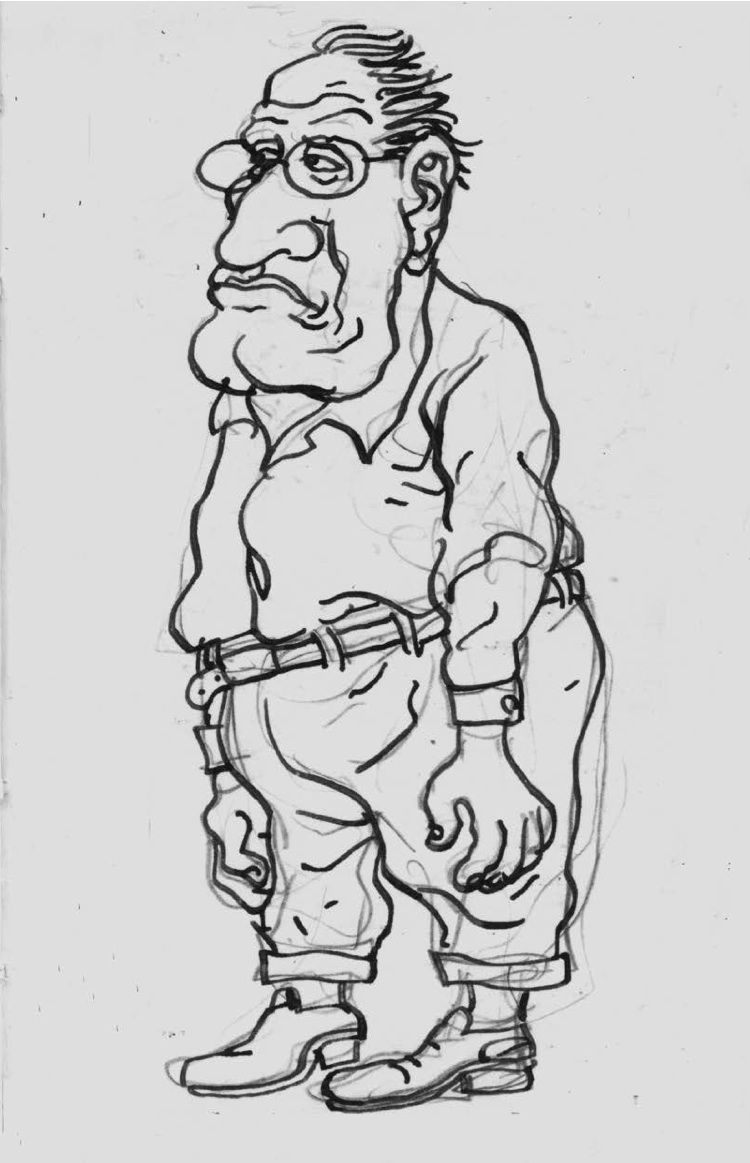

While not prevalent in the book, there are a number of sketches clearly drawn from life. How much do you rely upon referencing reality when working in your sketchbook, even when drawing something more surreal or fantastic?

Everything I draw is reality-based.