As the current David Woods Kemper '41 Professor of American History at Harvard University and a staff writer at "The New Yorker" magazine, Jill Lepore is considered one of the leading public intellectuals in 21st Century America. As an author, Lepore's work is noted for her skill as a storyteller and the way she deftly ties together the past and the present in enlightening and often surprising ways. Her new book, "The Secret History of Wonder Woman," ties together the Marston family, comics, the suffrage and feminist movement, family life, and how it all directly relates to the present day.

The book does tell the story of the life of William Moulton Marston and the lives of his wife Elizabeth Holloway Marston and their companion Olive Byrne, but it's really much more than a biography. It looks at the family's ties to Margaret Sanger (who was Byrne's aunt), the vast influence of the suffrage, feminist and birth control movements on their lives and on Wonder Woman -- both in the stories Marston wrote & supervised and in the artwork. While much attention has been paid to the unconventional lifestyle of the three, Lepore and the book are far more concerned with dozens of other issues the character of Wonder Woman and this web of influence raise, and what they say about the history of women and contemporary America.

CBR News: You've said that this book began with a piece you were researching for "The New Yorker" about Planned Parenthood.

Jill Lepore: It began a little before that. I had been working on a bunch of unrelated pieces of research, including a history of privacy, and a piece about the history of evidence. Then I had an assignment from "The New Yorker" to write about the history of Planned Parenthood. This was during the GOP Presidential nomination season, and all nominees had to sign a pledge that if they were elected, they would defund Planned Parenthood. The Planned Parenthood papers happen to be at Smith College, which has a terrific collection of women's history, and they also have Margaret Sanger's papers. I try, whenever possible, to read oral histories. As a historian, you're mainly reading people's letters and their diaries and things like that; you get a different glimpse of someone in an oral history. I was reading oral histories in the Sanger Papers and realized that people who were being interviewed about Margaret Sanger were people in William Moulton Marston's family. I hadn't seen or heard anyone noticing a connection between those two families, and I was just knocked out by that.

Your focus as a historian is primarily 17th and 18th Century America. Is there a connection between your work as a historian and books like this or your work for "The New Yorker?"

My big book-length works as a historian have been about seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century America, but I've always been interested in the whole run of American history. For "The New Yorker," I write on a range of subjects. It's a little bit different from the work I do as a scholar, but it's also very closely related to it. What I often try to do for the magazine is to write about something that we think is a problem in the present and then offer up its backstory. Planned Parenthood seems like a very present day problem -- the current debate over contraception and the Hobby Lobby moment that we're in now -- but Planned Parenthood was founded in 1916 by Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne when they opened the first birth control clinic in the United States in Brooklyn, and has a really twisty, turny, surprising history. That's a story I like to excavate and tell, because it helps us to think about present-day problems when we have a richer, deeper sense of the history. I never thought, gee, where did Wonder Woman come from? [Laughs] I took Wonder Woman for granted.

There were so many fascinating things I discovered in the book, but one was that there was this rich sub-genre of feminist utopian literature of the early 20th Century from which Wonder Woman emerged.

I had read that stuff in college, years ago, things like Charlotte Perkins Gilman's novel "Herland," about a woman-only utopia where there's no war. I read that stuff years and years ago and never thought about it again. When I decided to work on this Marston project, because I was interested in the ties to the Sanger family, I read "Wonder Woman" and "Herland" suddenly came back to me. I had seen "Super Friends" when I was a kid, and I saw Lynda Carter, but I never paused and lingered over the origin story about how she comes from an island of Amazonian women who live in peace and harmony and have eternal life. But then, reading the comics for this book, it struck me that Wonder Woman's origin story borrows from all the conventions of feminist utopian fiction. I had never noticed that tie before, and I don't think comics fans or comics historians necessarily noticed it, either -- mainly because there's not a great deal of overlap between comics historians and readers of feminist utopian fiction.

I was astounded by Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, who was married to Marston and was very well educated and very accomplished. I don't think it's well known that there was this generation of women, of which Holloway was a member, that was going to college and graduate school and was very accomplished.

The generation of women, like Holloway, who graduated from Mount Holyoke in 1915, are called "the new women." They went to college. They want to vote. They want good jobs. They want to have kids. They want to be married. They want to have it all. It turns out they can't really have it all. They write a bunch of magazine essays in the 1920s -- the essays are hilarious, but they're also really sad -- called, more or less, "Can a Woman Have it All?" They're exactly like the essays you find in most magazines today because we haven't solved this problem. These "new women" enter professions in the 1920s and 1930s and really struggle. Then women get factory jobs during the second World War, and then there's this incredible cultural push to get women out of the professions and out of industry. There's this incredibly intense period of ascribing domesticity in the 1950s. Comics historians think about the 1940s as the Golden Age of Comics and the 1950s they think of as having been shaped by Wertham and the comics code. Wonder Woman is shaped by those things, too, but much more dramatic, for her, is this longer history of the struggle for equality for women.

You make two observations about "Wonder Woman" that I wanted to raise, that it presented feminism as fetish, and the suffragette as a pin-up. So much seems to contradict the ideas Marston is putting not just in the subtext but in the text.

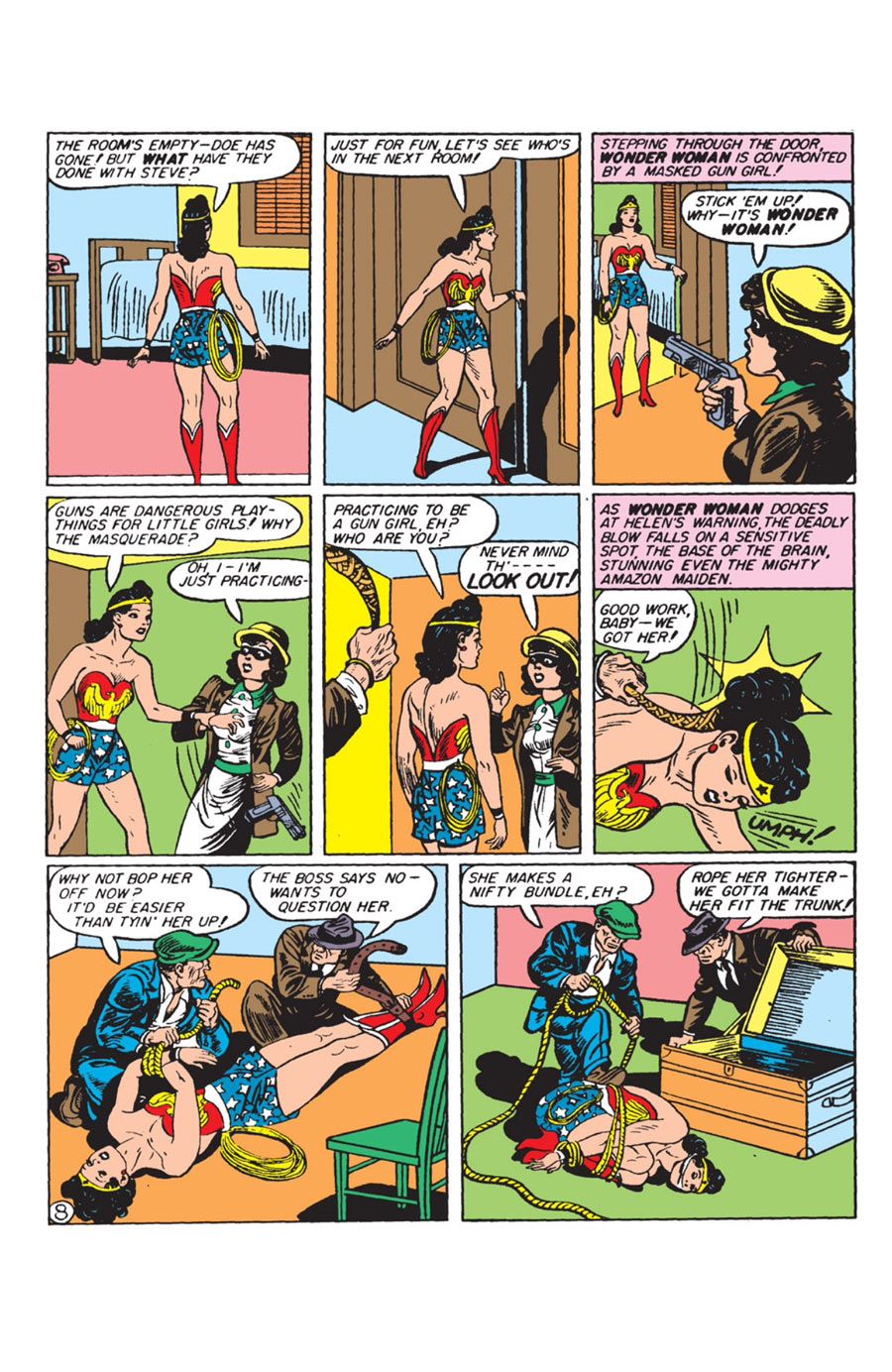

If you look at the comic books from the 1940s -- without any particular context or in relation to, say, Superman and Batman -- what you're struck by is all the bondage in "Wonder Woman." She's always chained up, tied up, bound and gagged and blindfolded in every story, and the fetishism comes across loud and clear. Then, you're left perplexed. What's the deal with this Wonder Woman character? [Laughs]

One of the things that I really wanted to do was to put that to one side, briefly, in order to reconstruct the role that chains and ropes played in the iconography of suffragism, feminism and the early birth control movement, where you see chains all the time. Women would march in chains, because this was political theatre, an expression of the idea that, without the right to vote, women are enslaved to men. Feminist cartoonist Annie Lucasta Rogers drew cartoons with women trying to break their bonds, all the time. Bondage was a central iconographic motif of the suffrage, feminist and birth control movements. So, when you have that in mind, the bondage in "Wonder Woman" begins to look more complicated.

In other words, emancipation through the breaking of chains of tyranny is the conceit that those political protests took, and Marston always insisted that that is what he was doing, too. He explicitly said, that is why Wonder Woman is always chained, and if a man chains her, she loses all of her Amazonian powers because she's submitted to the tyranny of men. When you look at the Wonder Woman comics of the 1940s, not against the Superman and Batman comics of the 1940s but against the iconography of feminism from the 1910s, then you might want take Marston at his word. Still, you can do that only so far. Because there's clearly something else going on in "Wonder Woman," too.

The interpretation of the bondage imagery is not usually considered in the context of suffrage iconography.

I think a lot of that, actually, is people who are thinking about bondage or kink culture today and looking for an origin story for that culture as opposed to looking at Marston's world, and its own origins. To find in "Wonder Woman" an origin story for kink culture is a fundamentally different intellectual move. That move begins in the present and looks backward to the 1940s. My intellectual inclination, as a historian, is to begin in the 1890s and move forward to the 1940s. That, generally, is how historians think: in chronological order.

Reading about the birth of Olive Byrne and how she was literally thrown into a snowbank by her father the way she was, I thought, that's the origin of a superhero.

It is! That's totally true. Someone should write that a comic book about Olive Byrne. I think Olive Byrne is a little like Olivia Dunham from "Fringe." Damaged -- but the power comes from the damage.

I kept thinking about Holloway wanting to take over "Wonder Woman" after Marston's death and run it with the same control Marston had. Obviously, it would have been radically different, but I kept thinking that Robert Kanigher and what he did was indicative of this postwar rollback of women's progress.

I really wish I had been able to find out more about Dorothy Roubicek, who was an editor for Shelly Mayer in the forties and then comes back in the late sixties working for DC Comics again, as Dorothy Woolfolk. In 1947, Woolfolk quit and had a baby right at the time Joye Hummel quit and Marston died and Mayer quit, too. "Wonder Woman" was left rudderless, and I was really fascinated to imagine, what if Holloway had taken over? But what Kanigher did to Wonder Woman, I think, makes us appreciate how utterly odd Marston's work was.

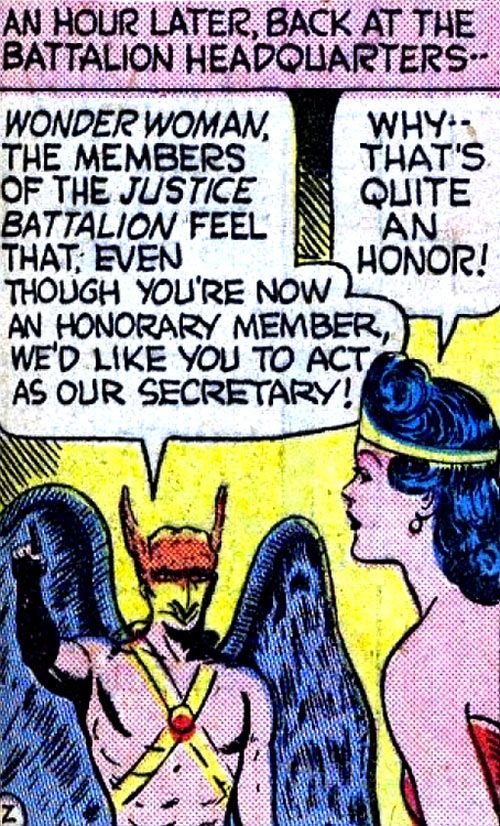

It was also really striking to read Marston's stories alongside the stories that Gardner Fox writes for the Justice League for "All-Star Comics." Fox just couldn't think of anything for Wonder Woman to do except to type the meeting minutes and answer the phone. You almost expect her to put on an apron and start dusting. But Marston had Wonder Woman do everything. She organizes boycotts, she tells women to leave their husbands, she runs for president. It's pretty extraordinary stuff. On the one hand, if you want to say, well, Marston wasn't really a feminist and this was in fact a subversion of feminism, that's a totally acceptable reading. On the other hand, compared to Gardner Fox? [Laughs]

Then, when Kanigher returned to edit and write "Wonder Woman" in the early seventies, it felt like a response to the previous few years -- not just the changes to Wonder Woman, but the changes in the culture. I mean, he opened his first issue by killing the previous editor, Dorothy Woolfolk.

I spoke with people who worked with Kanigher at that time, and he was just a certain kind of guy. He did not have any capacity to respond to women's demands for equality except with venom and hostility and defensiveness. There were -- and are -- a lot of people like that. The thing that I find so fascinating was how so many women of that generation, joining the women's liberation movement, were thrilled to have Wonder Woman as a feminist symbol. Even Kanigher's version of Wonder Woman from their childhood in the 1950s -- as relatively powerless as she was compared to the Wonder Woman that Marston had written -- she meant something to those women. My favorite example of the way women in the women's liberation movement re-claim Wonder Woman is a Los Angeles Women's Health Collective that put Wonder Woman wielding a speculum on the cover of a newsletter that contains, inside, a guide to how to conduct your own vaginal self exam. In some ways, that is completely perfect, of course, because Wonder Woman really is inspired by Sanger and Ethel Byrne, who were arrested on charges of obscenity for distributing information about how to use a diaphragm. There's something lovely about how that closes that circle.

One thing I was thrilled to learn was that Joye Hummel, who wrote a number of the early "Wonder Woman" stories, is still alive.

It was amazing to talk to her. It took me a very long time to find her -- she's a very private person, and I entirely and deeply respect that. I went to see her and she pulled out of her closet this big box, filled with more than a dozen original scripts and notes and copies of her comics and letters from Marston, receipts for the stories she had written, her work calendar. She had this incredible trove of material. She was delighted to talk about it. She hadn't gotten anywhere near the credit she deserves for all the writing that she did. She worked for Marston between 1944 and 1947, then, in a very great act of generosity, she decided to donate all of her incredible material to the Smithsonian to join a collection of scripts that Holloway had given after Marston's death. Now, people can go read the scripts that Hummel wrote with Marston, and some that she wrote herself. This means that future scholars will be able to look at the history of Wonder Woman in a whole different way when trying to chronicle the contributions of people that haven't been appropriately documented -- which, in the case of Wonder Woman, is mainly women.

I don't think you have an answer, but do you have any sense of why Byrne was so intent on keeping everything such a secret, even from her own children?

That is a little bit of a puzzle. I guess the way I understand it -- and this is speculation that I wouldn't feel comfortable putting in the book -- she's a woman who was literally thrown into a snowbank as a newborn, and grew up in orphanages and convents. She desperately wanted to be in a family. She wanted the legitimacy of family life and nevertheless made this choice to live in a very unconventional way at a time when it was very difficult to live in an unconventional way. So she invented a story about a marriage and her husband's premature death, and then her kids have a way of living in that household without being exposed to censure or ridicule or gossip. She felt profoundly protective of the kids and invested herself in that fiction and never let it go. But you're right to say, I do not know. I think the ways of many people are largely ineffable.

This idea of "having it all" is as much an issue today as it was a century ago. This arrangement the three of them had allowed Holloway especially to maybe not have everything, but get as close to it as she could.

The kids will say they were loved by everybody and, somehow, it just worked. Holloway loved to work. Olive Byrne really loved being home with the kids. Marston delighted in the arrangement. The kids speak with great fondness about their childhood in a "Cheaper by the Dozen" way. Still, the need for secrecy was a difficult thing for the children to bear.

Again, my inclination is to pull back from that and ask, what about this set of arrangements shows that it is really difficult for two people who want to have children together to also have meaningful work? It's almost as difficult today as it was one hundred years ago. Why is that problem so intractable in the United States? Because I'm a political historian, that political question is, to me, far more interesting than the narrow biographical question. As curious and fascinating as the family story is, to me it's chiefly a prompt for other interesting structural, economic, cultural and political questions.

When Sanger was sentenced in 1916, the judge said if a woman isn't willing to die in childbirth, she shouldn't have sex. A lot of people would argue that today. There are a lot of aspects of these issues that haven't changed in a century.

There are people who would still argue that. When Ethel Byrne was in jail on a hunger strike in 1917, there was an editorial in "The New York Herald Tribune" urging the Governor to pardon her because people didn't want Ethel Byrne to die in jail. The way the editorial writers berated the Governor was to imagine, "Fifty years from now, are people going to look back and be scandalized that a woman had to die in order for birth control to become legal?" And it is scandalous, but it's also sadly prophetic: 1967 is only two years after Griswold v Connecticut when birth control was declared to be legal. It took fifty years for the fight to be won, and it's not even really won.

I kept thinking of this book as a sequel of sorts to your last book, "Book of Ages." That book was more than just about Jane Franklin -- it was about how we think about history and how that period has been constructed. This book is about more than Marston or Wonder Woman, but about this era and rethinking how we think about it.

Interesting. I hadn't really thought of it that way. "Book of Ages" is absolutely about the writing of history and how history is written from what survives -- and in that case, from what doesn't survive. Because women were not taught to write in the eighteenth century, to record the ordinary life of a woman like Jane Franklin is unusual. This book is similar in a sense, I guess, in that there's a surprising discovery that the history of Wonder Woman is filled with -- stuff that we never knew, that I never knew, things that were generally not known, but for a very different reason.

In the case of Wonder Woman, the historical record isn't impoverished because it doesn't survive -- it's impoverished because the true story was kept as a family secret. That secrecy meant that the political origins and the biographical influences on Wonder Woman were hidden -- and lost to a very important political history of the twentieth century. But this particular family secret leaves a hole in the middle of the twentieth century. People often think of the women's rights movement as having taken place in waves: There's a first wave that ends with the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920, and a second wave that begins in the sixties, and in between those two waves, it's as if there's nothing going on. But, once you lift the veil on the secret history of Wonder Woman, right there in the middle in the 1940s, there's Wonder Woman, inspired by the feminism of the first half of the century, and an inspiration for the feminism in the second half.