Writer Joshua Dysart may be best known for his work on Vertigo's "Unknown Soldier" from 2008 to 2010, which saw him spend time in southern Sudan, extensively researching child soldiers and refugees for the title's relaunch. While he's recently made waves at Valiant Entertainment with "Harbinger" and "Imperium," Dysart opened up on his trip to Iraq in 2014 to gather material to write the 35-page graphic novel, "Living Level-3: Iraq" Vol.1 (currently free on comiXology). The book is drawn by Alberto Ponticelli and was originally released last January as part of the United Nation's World Food Programme's initiative to alleviate hunger and offer aid to Middle Eastern refugees.

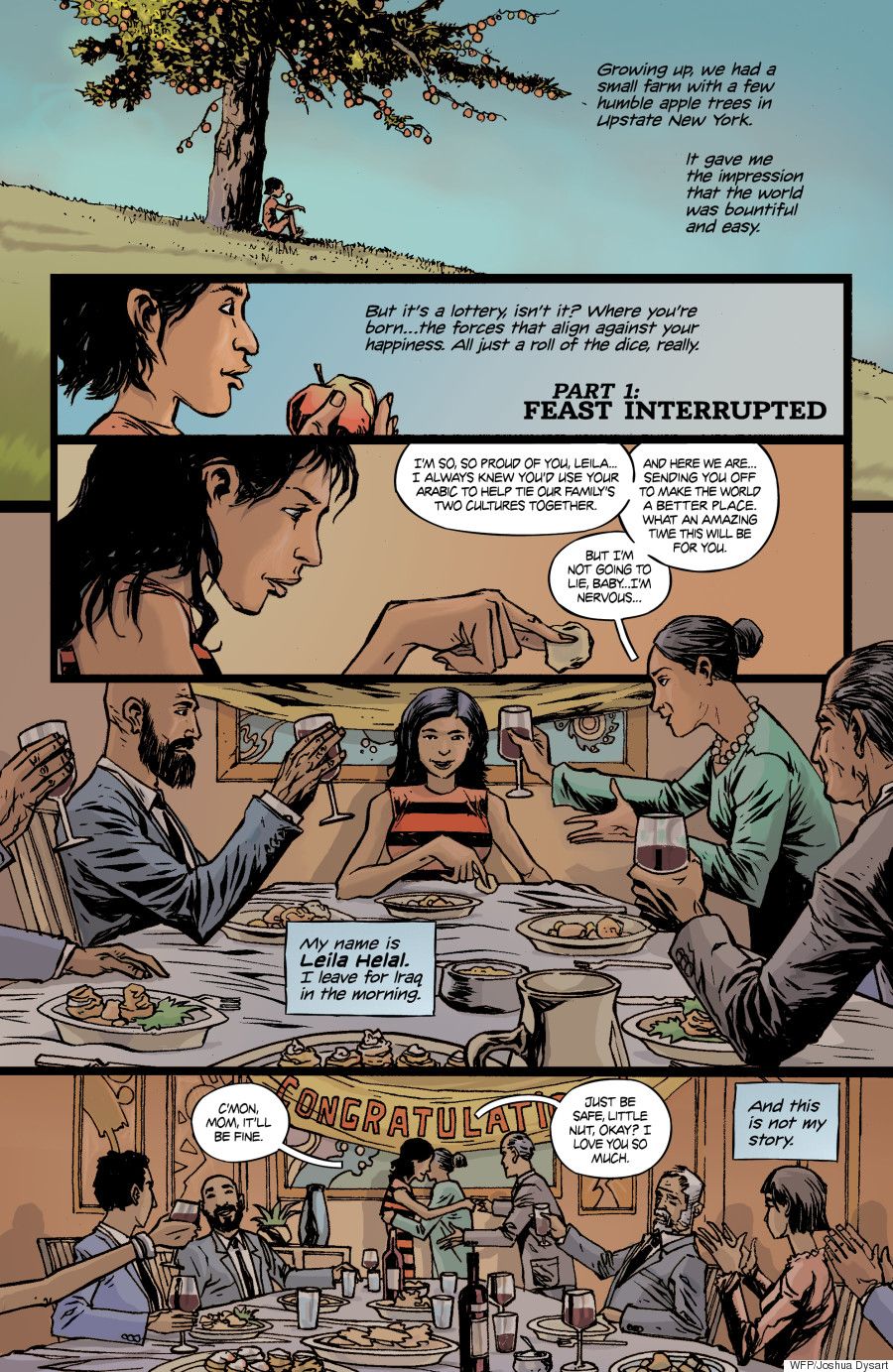

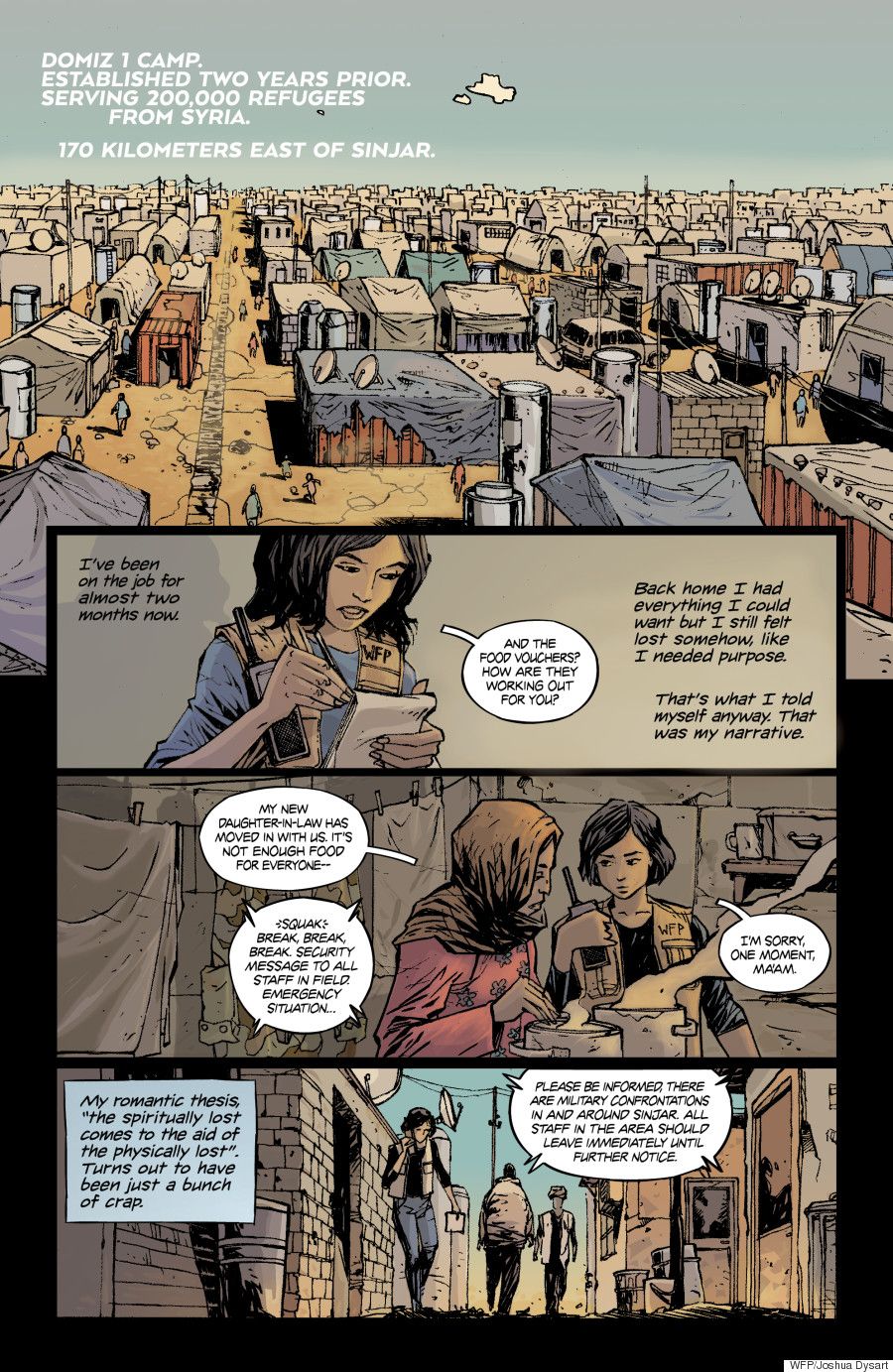

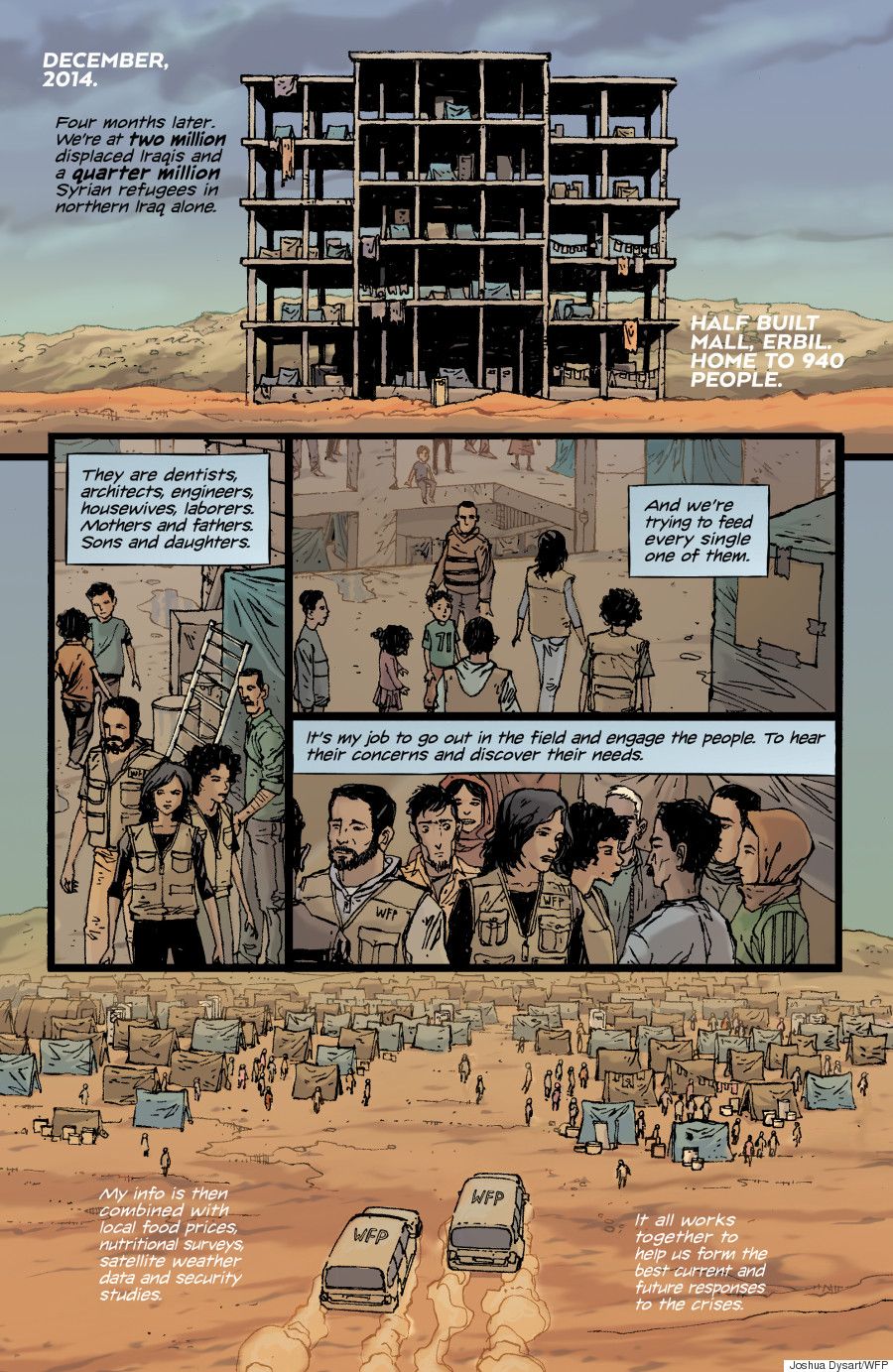

"Living Level-3: Iraq" is the brainchild of Jonathan Dumont (a Bostonite now living in Italy) and Gioacchino Gargano, both of the WFP. The story focuses on highlighting the work of the organization's humanitarian aid workers and those they strive to help. The title refers to the most severe classification of humanitarian crisis, and the comic tells the story of a fictional humanitarian aid-worker, Leila, on an aid mission after the self-described Islamic State brutally seized territory there in 2014.

This awareness-raising project focuses on the struggles of the war-torn region, combining fiction with Dysart's real-life documentaries taken on-site. The writer returned to southern Sudan in the first week of May 2016 to begin researching for a 40-page follow-up and second volume. CBR News spoke with him one month before he left for South Sudan, as Dysart discussed the debut volume and his lifestyle of, as he called it last month on Twitter, his "schizophrenic mix of comic art & global politics."

CBR News: Joshua, could you share some insight on how LL-3 came to your table?

Joshua Dysart: Originally, the United Nations World Food Programme -- it was their idea to do a graphic novel like this as part of their reach-out and media program. And they approached a comic book writer by the name of Ande Parks, who's a close, personal friend of mine. Ande Parks did "Capote in Kansas" and some other really lovely graphic novels. At that time, they wanted him to go to Boko Haram-affected parts of the African continent and he said no. [Laughs] But he said, "I know someone who will go" -- and so he directed them to me. And as soon as I found out the nature of the project, I lobbied pretty extensively to get it because when "Unknown Soldier" was over, there was -- there has been -- something definitely missing from my life and from my work. I've had fun and I enjoy the comics that I make, but there is this other dimension that was missing so the minute this opportunity arose, I saw it as a chance to get back to the kind of work that is completely fulfilling to me as a creative person.

For "Unknown Soldier," you went to Uganda and experienced the hardships in Africa, correct? In these kinds of projects, you venture into hostile territory. Aren't you scared? How does your family react to these ventures, especially with Iraq being the destination now?

That's correct. And in South Sudan before it was a country -- when it was just a part of Sudan. The summer of 2014 was the summer of Daesh. They exploded across Iraq. The official Iraqi military ceased to exist. The Peshmerga suddenly reemerged and held the line so it wouldn't even make sense except to tell the story in Iraq at that time.

There's always this moment, you know, when you're making your plans and you're fueled by excitement. This is always a hard discussion to have because it sounds exploitative and it very well may be exploitative to a certain degree, and I've to talked to a lot of war journalists and aid-workers who have been in far more dangerous situations than I have and certainly, it's not all altruism. There is something in you that pushes you to go to these places and want to be a part of this and there is something dark in you that wants to be there. You just hope that you turn that energy into something positive and good for the world...and for the people who have to live and don't want to be there -- who are forced to be there.

Then the night before you fly into low-impact guerilla war-zones, like where I was in northern Uganda or a relatively active zone like I was in Northern Iraq, it's terrifying. You are scared that night. You wonder what you've done with your life and what you're going to do. This trip to Iraq was a little bit different. When I went to East Africa, I went by myself. When I got off the plane, I took a bus, I took public transportation, I rode on the back of boda-bodas, which are these sort of motorcycle taxis -- into the bush and there was no security for me at all. It was during the period of a ceasefire in that conflict but nonetheless, I now look back on that and realize that was a tremendously foolish thing to do; whereas going into Iraq with the WFP, I was part of the WFP security bubble which is an enormously effective, professional, well-honed security response bubble around you that you don't even necessarily see. You're not armed or anything but you have constant radio contact. Everyone knows what's happening in the region at all times. You don't eat at a restaurant that hasn't been vetted. You don't get in a car that hasn't been vetted. You're not out overnight. They sort of invisibly manage you and it felt much safer. Of course, you're there with people who do this every day, who have chosen to work in these zones and you're also meeting people everyday, who... this is their home and their home has been destabilized. Your own personal fear sort of evaporates in the face of aid-workers who have chosen to be there and of course, the population that's dealing with these destabilizing factors. Is my family worried? Sure. My mom doesn't even really totally understand until I come back with the pictures and the stories. My fiancee is worried. They worry for you but you have to walk your path, right?

Well, factoring these loved ones in, do you ever feel like you could get interviews or transcripts done via recording or Skype or phone call? Or get some of the aid-workers to do it for you? Why be on the dangerous ground zero?

The people most impacted and affected by the destabilization in these regions are not someone you can Skype with. They're living in more than just poverty. It's internally displaced persons [IDP] camps. It's these massive, sprawling refugee zones and communicating with them is a technological problem. But that's not the real reason to go. The real reason to go is because there is something about being there and talking to those people face to face and looking at their homes they live in now and being told about the homes that they had to flee and all that they have lost. All their possessions, their bank accounts drained, their homes taken over. And they have also, more importantly, lost people -- children, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters -- so it is your responsibility now. If your hope is to go there and to be told their stories, if you're going to further invade their lives -- and you're a much more passive invasion, but nonetheless -- come in and sort of, for lack of a better term, exploit their narrative... the least you can do is go and eat the meal that they've prepared and sit in their home such as it may be. And in this case their home is a cargo container given to them by UNICEF or a tent that an aid foundation has set up for them somewhere in a field or a half-abandoned construction project that the rain leaks into. The least you can do is be there in their home and hear their stories and hug them and hold their hands and walk the ground that they walk. And then the little things -- the tangible nature of being in a place and witnessing a thing instead of being told the thing... that makes it into the bones of the work too and you feel the difference -- a real difference between Google research and something you have observed and processed and that you have your own opinion about and your own commentary on as a personal experience. And that is not to say that the five days I spent in Iraq or the one month I spent in East Africa in any way makes me an expert but it's just this tiny little slice that you owe it to these people to go to them after all they've been through. Otherwise, it's just exploitation for exploitation's sake.

Getting into the comic, Leila, she's the upper-class protagonist who left America to come to the fore as an aid-worker with the WFP to Iraq in the story. She finds herself in the midst of families devastated by loss as well as intersecting military forces... so I ask, what inspired her origins and how did you put the character together? Found parallels to her and yourself?

Firstly, the parallels between Leila and myself? Absolutely. She's more of a mouthpiece for me than a character. I tried to give her her own sense of self and with the page allotment that we had, it's a pretty short book and that's problematic when it comes to building out character. So she absolutely represents a lot of my concerns about this story that I'm telling, whether I deserve to tell that story and of course, through her lens -- why is she there? Does she deserve to be there? What is her perspective on this thing? She's also a way for me to explore the global class divide. She's relatively upper-class. Her family owns land in upper New York. Her father flies her first-class to a war-zone, which is my little comment on global classism and so her observations are as an intelligent person but also a privileged person. Like... I am a privileged person. I won a lottery to be born in this country [USA] where we have relative stability and relative to what that region is going through, it's a real lottery. And so, that's exactly who she is. At the same time she is also very much an amalgamation of many young people that I met working for WFP on the ground and in that instance, she's also sort of my ode to the young aid-worker or the young person who decides to do something. And not mindlessly or with some sort of mission but to just be a part of the world.

You mentioned it was a compact story which would restrain how you build characters and things like that. So how did you go along balancing and adapting fictional characters with real characters you encountered?

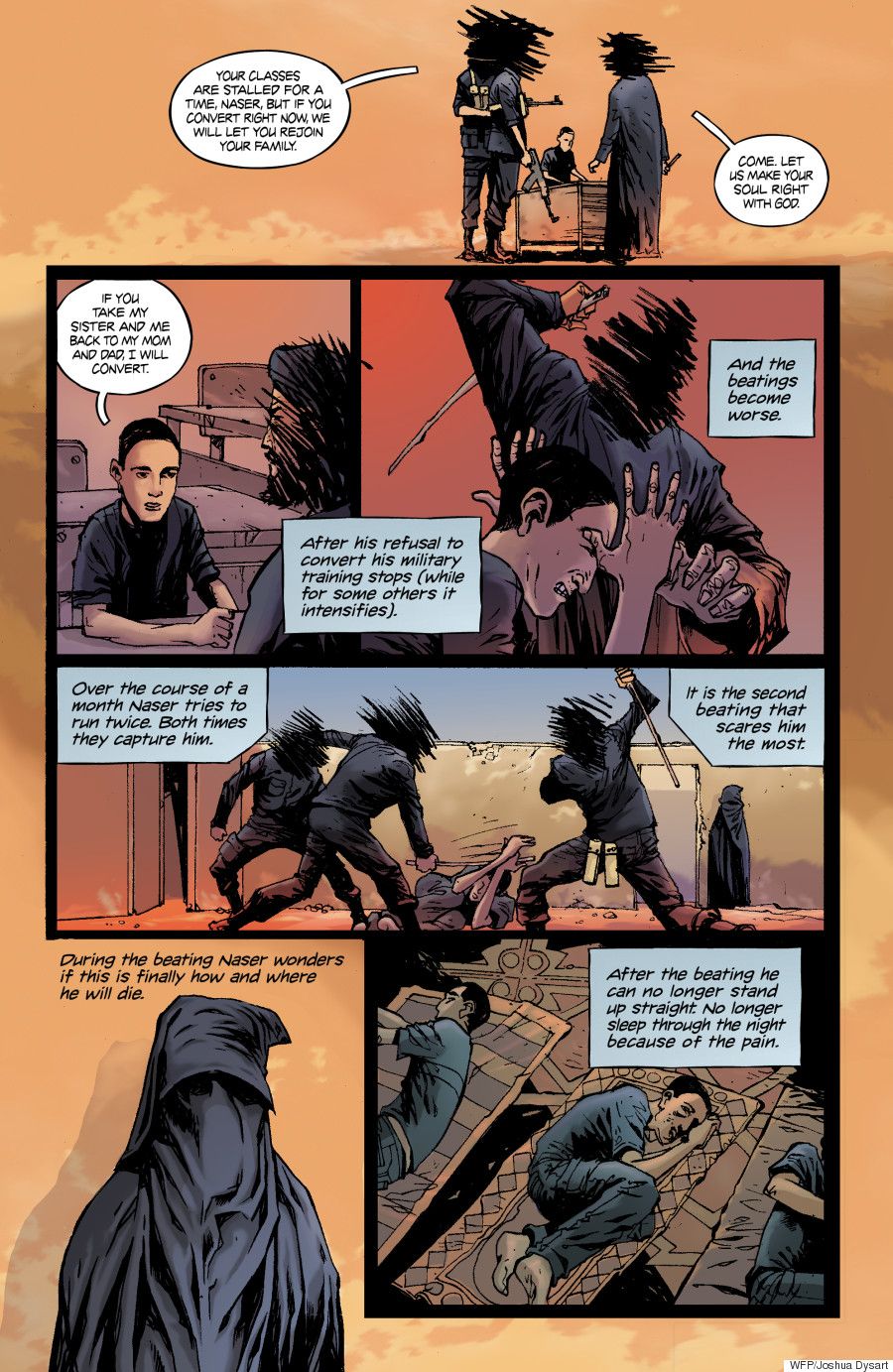

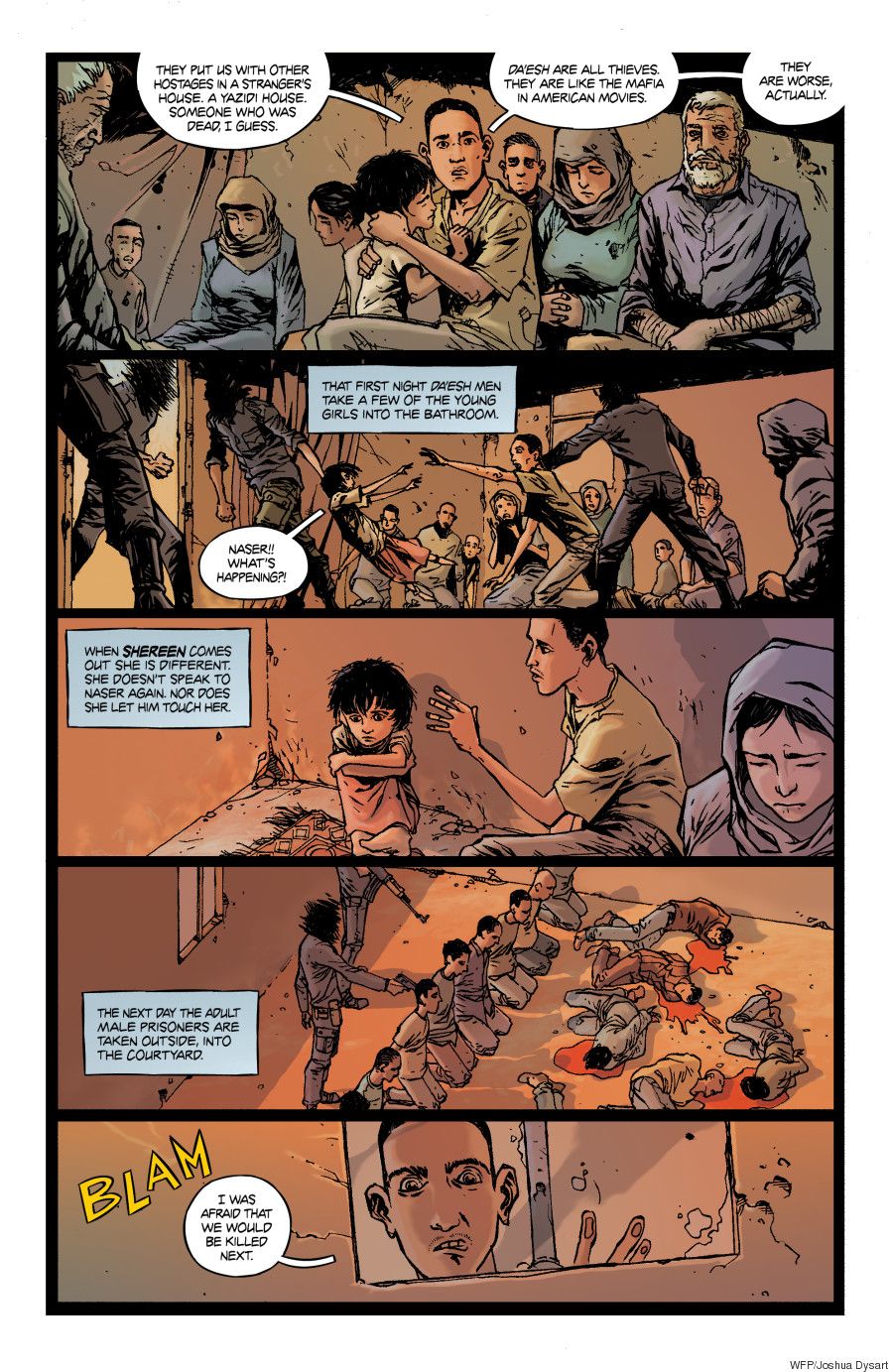

This is the biggest challenge of this project because we had this compact space. I wanted to talk about a lot of different kinds of people because it's supposed to be about life in a war zone and I wanted to basically talk about everyone but the soldiers. So all the characters are fictional but some are kind of larger conglomerates of people than others. There is a character in there who is an aid-worker for WFP who discusses when he was in Baghdad during the American bombing of Baghdad -- the shock and awe. He's almost based entirely on a real person -- an Iraqi who I traveled with and that is his story. And that was just taken whole-cloth and I hope he doesn't mind. That's a real story. The story of Khaled, the boy, and his sister, with some details extracted solely for space -- that's a real story that one person went through as well as his parents. But other characters are sort of amalgamations, like Leila and some of the other aid workers she travels with. So there's this really fine line you're always walking with this kind of fiction. It's technically fiction but the purpose of this fiction is to tell a greater, deeper observational truth. And so you have to be really careful with these characters that they are as true as possible within the fictional confines of the work.

The team behind LIVING LEVEL-3: IRAQ. Left to right. Alberto Ponticelli, me, @patmasioni. Taken in Algeria in 2014. pic.twitter.com/wH4e7vRC8G- Joshua Dysart (@JoshuaDysart) January 22, 2016

How many families like Khaled's did you encounter and interview on your five-day trip?

Khaled is based on a very real character and a very real family. The only details changed in his narrative are pieces that were removed so that we could fit it into the space provided. However, I couldn't even tell you how many people I spoke with for those five days because that's all I did -- go from camp to camp and speak to people and refugees who were fleeing either the Syrian conflict or Daesh in Iraq. I couldn't even give you a figure. All we did was ride in convoy from location to location and speak to people. Some of them I had dinner with and they cooked meals for me using food they purchased with WFP vouchers which was really a very extraordinary experience. I would spend an hour with some of these. Some of them you only get two or three minutes with -- just you, the translator and them. Some of them were women alone so because of certain aspects of their culture, you could only talk to them for a brief amount of time and then the female translator would take over and you would step away. And then the female translator would come back and tell you things they told her. With Khaled's family, I specifically went into their home and they're Yazidi so we needed a different translator. We spent a couple hours with them. There are just some organizations you walk away from and think humanity is inherently good and that's how I feel about WFP.

What jumps out at you to do these kinds of stories as opposed to the comics you do for Valiant and other publishers, mainstream and indie?

Well, comics is what I do and I am involved or inspired with the world and with people. I love writing comic-books. It's a super-interesting job and at the same time, I not an escapist by nature. When I need inspiration for my comics, no matter how escapist they may seem on the surface, I'm always looking at my life or the lives of others and other things that are happening in the world for inspiration. I'm not one of these cannibal writers who looks in a superhero story and thinks that I want to do them. When there's an opportunity to be a part of something that is important, I leap at it and it's kind of been adverse to my career but it makes me feel more fulfilled and part of the planet. Also, I really like people. People are just amazing. We have so much potential yet we can be so cruel. There's something really beautiful about that so I want to go where people are being really human to one another -- both kind and horrible. I want to see that, I want to be part of it and I want to bring those stories back. This is about trying to disrupt the idea of the other... in the minds of the reader. We were halfway through when the migrant crisis poured into Europe and stressed the European ability to host the other. Then I realized it's about breaking down the wall. I can show you that we are more similar than we are different. We laugh the same way. We love the same way. Maybe I can increase your empathy load a little bit. We all want what's better for our families.

How tough is it seeing kids and families wrapped up in Daesh and stuff like that?

It's an utter nightmare. You go because it's tough and you look around at the world you live in. I live in Venice Beach, California, where the weather is always nice. We have a gentrification problem and a homeless problem but it's not anything like what they're experiencing over there. That's where people are suffering the most. I think it's our jobs as human beings to go and witness and speak up and try to alleviate our brothers and sisters' suffering. They need their voice to be amplified. This comic-book is a megaphone allowing the Yazidi and other ethnic groups to discuss what's happening to them under Daesh.

What were some of the scariest things that shook you over there?

When you're there, things are happening so quickly and you don't think a lot. You hear the stories and a lot of the processing happens later. There was never anything scary. WFP took a care of their people, keeping them safe, but for the most part, it's just the weight of stories. It's the wave of empathy when you're hearing what happens to these people who flee Daesh and the Syrian conflict. When you're there and hearing the stories, you're in a very analytical place and it's not until when you come back to safety that you begin to process and start writing... that's when you start to deal with guilt and other things that are hard to explain.

So you documented these stories and came back with material. Describe the process of now making the comic happen with the artist, editor and WFP?

The process went very slowly for a couple of reasons. Basically what I did upon coming back [to the states] -- we had already built the art team and were sort of ready to go. I didn't have a real editor. I just had a friend who was helping me keep schedule with artists and stuff and the [WFP] communications team in Rome as this project was their brainchild. The WFP did get all the scripts but I never got any editorial hand in the story. Everybody was happy with the way the scripts were coming in. Really, the process of writing it is you sitting alone in a dark room and deal with this massive avalanche of narrative you've been told by these people. And dealing with the weight of the responsibility that you have now to get all of those stories to the best of your ability into to this very contained, little item of narrative -- this 35 page comic-book. It was hard. You really feel like every single little thing everyone told you should be in the comic. So you conflate stories and that's where you have an ethical battle with your craft as a storyteller but also with the ethical idea of what fiction can be. And it took a long time to write those 35 pages. It was a battle for me.

Was the art-team pre-assembled?

Once they brought me on board, I began to float a couple different artists to them [WFP] in Rome to see what they were interested in. I showed them a lot of different styles -- Ronald Wimberly, Greg Ruth, Pat Masioni who ended up coloring the book... and Alberto Pontecelli, because he and I had done Unknown Soldier together and I view him as my brother. At first, they actually chose Pat, and I'll always have some guilt about this as Pat began gearing up for the project, but then once we got up and rolling... I guess for pragmatic reasons, they switched to Alberto because he's Italian and there in Rome, I guess they thought it'd be frictionless to deal with Alberto. So I brought Pat on as the colorist so he can still be on the project. It was a shifting roster. I wasn't going to let them pick without me as I'm not a big fan of people choosing the artist I'm going to work with. That's a pretty intimate relationship.

I've heard a lot of intimidating things about Sinjar. How was the experience and relaying the visuals to the creatives?

I've never actually got to be near Sinjar but I was close as we went up to the Syrian border. Honestly, Northern Iraq is really pretty. It looks a lot like Central California. It's rolling and I was there in December. It was about to get cold but it wasn't that cold yet so everything was green. Pat, who was coloring the book, kept laying down browns because we just view Iraq as a desert nation. And it is that. There are a lot of parts that are arid but as you start heading north and you get closer to the Turkish border, it gets more verdant and green. So we had to give him notes for a little bit more green. That was kind of interesting -- the perceptions we have of a place and how that perception changes once you're there.

What period specifically were you there?

December 2014. I was there December 17, 2014. That's when the Peshmerga group began the liberation of Sinjar and that's in the comic -- we really did cross paths with a mobilized Peshmerga unit. If you go to my website and go under the journal page, you'll find photos of that group. At Christmas, there was a lot of people who didn't know I was going. Mobilizing happened really rapidly so many people didn't know I was there until I came back. It wasn't always Iraq as I was discussing aid work for a long time for Boko Haram-affected areas.

How did production go once you got back in with all the Valiant stuff on your plate too?

Upon returning, I spent January of 2015 working with Pat on a flyer -- a silent comic one-sheet. We created a wordless comics designed how to teach people to use these food vouchers, wherever the necessity is. Then we started the comic in February 2015 and it took us the rest of the year to put together these 35 pages. Alberto had a lot of work in his schedule. I also had a hard time writing it and wrestled with what was appropriate and what was genuine. I was initially budgeted for 20 pages so I hijacked the project. There were all these situations that made it take longer than it should have.

In Chapter 4, there's an unspoken incident with a young female, Shireen, which we can assume is sexual assault. How hard was it putting this in the story and was there any other extreme stuff that couldn't be put in?

I don't want to be dishonest and I need the reader to know exactly what's happening there. At the same time, it don't want it to be unreadable. Shireen is based on a real person. I met her family. Shireen is a huge part of this conflict. When a young woman gets captured by Daesh -- the odds of that family seeing Shireen again are miniscule. I hope everything we tell lets you feel the rage and the sorrow but doesn't stop your reading. To discuss violence as a virus is a lifelong research project for me. When I was 24 or 25, I was travelling through the revolution in Chiapas, Mexico. I saw tanks on the move. Men with guns. Thousands of Chiapas Indians marching in Mexico City. Something in me turned on and changed me and I've pursued trying to understand why we harm each other. It's always for greed, to be honest. That research is lifelong.

This malnourished arm belongs to an 18 year old girl. I met her Sat. Tell the world about Aweil, South Sudan now. pic.twitter.com/ggzFJffj0i- Joshua Dysart (@JoshuaDysart) May 10, 2016

You're documenting heavy stuff -- child soldiers, kidnappings and such. How is it reliving these moments when writing in terms of the emotional toll?

The first thing you do is question if this is even the right thing to do. Like who am I to go there to hear these stories and create populist entertainment with them? There is a very real discussion with ethics that people should do around these projects I do and I love these discussions. Sometimes, I feel like I'm the most postcolonial person who has ever worked in comics and other times, I feel like the only one who tries to give a voice to populations that don't have access to this same audience. I oscillate back and forth between those two opinions of myself. But once you get past the guilt, the doubt and the ethical struggle of the work, you're just dealing with the experiences of these children. And this has its own guilt. Those people certainly don't deserve what they've experienced. Their fate is out of their hands. You don't live the stories they tell you. You hear them. While there is such a thing as PTSD that the listener can have, it's nothing compared to what these people have been through.

When you look at freedom issues, democracy issues, race issues -- all popping up within America, how does that affect your storytelling as you see so much outside USA as well?

We do have to put it in perspective. We still have the rule of law in America, which is unquestionably serving some populations better than others. For example, that's what Black Lives Matter is about -- social justice. That's very important. A nation struggles to become a better nation no matter where it is on a sliding scale of stability and rule of law. In the US, we are struggling to be a more just nation, of equality and democracy, which is being illustrated by our insane presidential election right now. But it's different to the rule of law of say, Southern Sudan or Syria -- where their struggle is one with guns, with ethnic cleansing. When you travel to these zones and come back, your perspective is so much bigger. But at the same time, I'm an American and I want to see this country be exceptional and live up to the ideals it purports to live up to. Nothing kicks up dust like a horse with its ass on fire.

There's a lot of humanity in this story but were you ever worried over how it'd be received? Given the medium's most-known for superheroes in tights and escapism.

I feel the opposite. I think it's the perfect medium for it. I think this story can come off as dry, too professorial and too preachy so people may shy away from it but I tried not write it this way, of course. The medium has no motion or sound so when you engage with it, you're in more control as a reader. Comics is perfect for this kind of storytelling and I wish it'd do more of it. I think one of the great tragedies of American comics is that they're almost entirely monopolised by superheroes. But this is changing. Funnily, as film, as American cinema becomes monopolised by superheroes, comics seem to be less interested in superheroes. This is exactly the kind of projects comics should participate in -- part of the global human conversation.

What about the follow-up with the next volume in South Sudan? I know that area holds a place close to your heart.

The intention all along was for this project to be part of a bigger project. I've always been interested and engaged with life in conflicted zones, whether that's zones conflicted by geopolitics or conflicted by calamity. And the least interesting person in a war-zone to me, is the soldier. Even though we pulled a sleight of hand with "Unknown Soldier," it seems to be about a soldier fighting a large resistance army but in fact, it's really about other people in the war zone -- civilians, aid workers and celebrities in some instances. And so my perennial fascination is how people live, manage and survive in utterly disruptive cultures. So I absolutely intend on continuing as much as WFP will allow the "LL3" series and I also intend after that's done to continue to pursue my exploration of civilians in war time. It's just an itch I have to scratch.

It's really something to live in a stable environment and I personally feel like I owe it to tell the stories of people who don't have that. That's how I earn my place in this stable culture -- by amplifying the narratives of people who are not as fortunate as I am. Yeah, I intend to keep telling these stories.