The elevator pitch for new Image Comics series Infidel is “Get Out with Muslims,” but that description is really selling the series’ complexity short by a large margin. In Infidel, the creative team of writer Pornsak Pichetshote (best known as a longtime Vertigo editor), artist Aaron Campbell (James Bond and The Shadow at Dynamite), colorist/editor José Villarrubia (who has worked on basically everything) and letterer/designer Jeff Powell are exploring something beyond how Muslim Americans are seen in this country. They’re exploring how we talk about issues of race and bias, and more importantly, how we misunderstand one another and how our inability to communicate slows social progress.

As for the Get Out comparisons, they’re not all bad. “I was [a fan of the movie],” Pichetshote said, laughing. “It’s funny, because I had the story for Infidel for so long -- it’s one of those ideas that I figured somebody would do sooner or later, so when I saw Get Out I figured somebody beat me to it! But in a weird way, there’s a benefit to going second. It provided a way to talk to people about Infidel, even though what we do is very different.”

RELATED: Lemire & Pichetshote Reveal Secrets of New Series Gideon Falls, Infidel

Campbell agreed, saying, “[It’s] almost proof of concept. It’s proof of genre really, because it’s kind of a brand new genre: topical horror.” Villarrubia particularly appreciated Get Out, calling it “flawless” and saying that it marked “a revival of psychological terror, and that the torture porn trend in film horror had mercifully passed. Get Out led me to catch up with other recent horror films with topical themes like The Babadook and It Follows.”

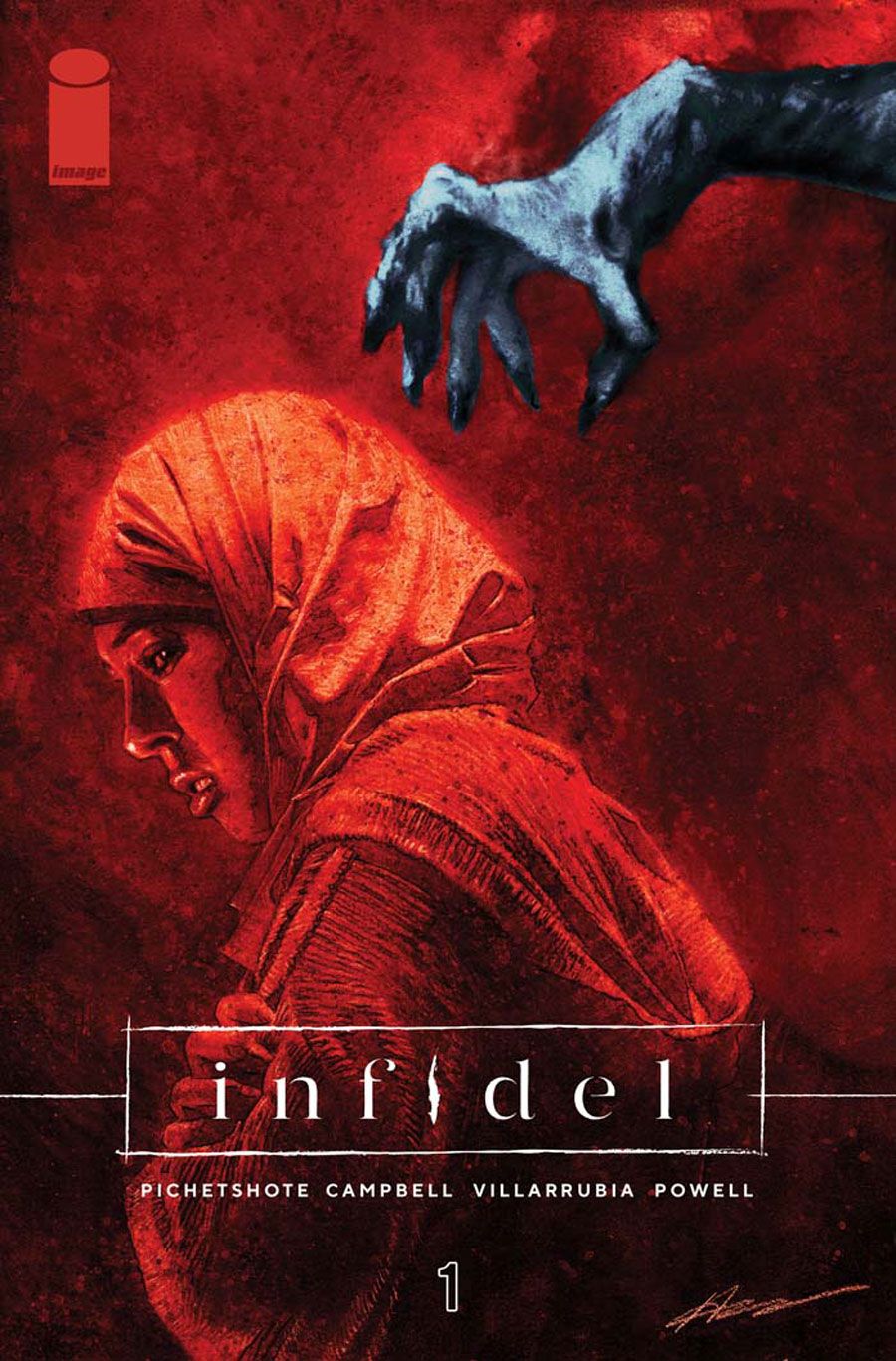

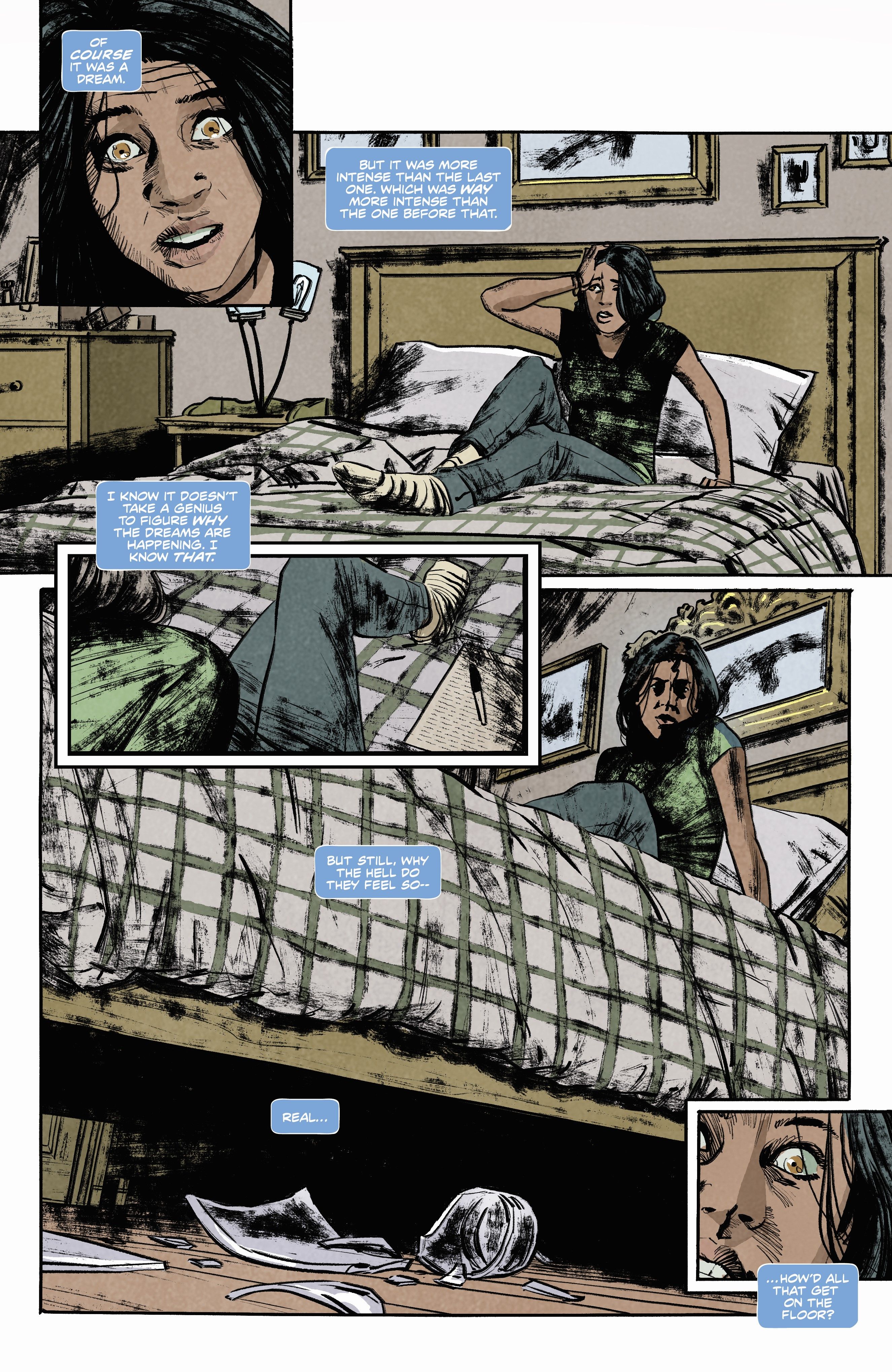

But despite the comparables, all three made it clear that they have their own story to tell. Infidel focuses on a Muslim-American woman named Aisha living with her white boyfriend Tom, his mother, and his daughter in a haunted apartment building -- haunted by ghosts with their own horrific tragedy that fuels their rage. The effects of that haunting ultimately push all the characters to confront how they perceive each other and, more importantly, how they are trapped by those perceptions.

“Much of this book is about xenophobia, Islamophobia and racism, [but] Aaron and I talked a lot about this: there is, especially with race, a hunger for a conversation, but we haven’t had it for so long that we haven’t really developed the language for it,” Pichetshote explained. “It’s been an interesting thing to watch, how when we talk about race, there’s like a little timer in our head and we’re just waiting for somebody to fuck up. It shows how much we haven’t developed this vocabulary to talk about something so integral, especially when you tell a story and you talk about mixed communities and people interacting. So much of the conversation in Infidel comes from the idea that we’re still kind of bumbling in the dark for how to do that, which is interesting because so many people, and certainly the characters in the book, are really grappling with this. One of the impetus behind the book [is] to start a conversation and have that conversation inform the story.”

“You can go into a conversation with the best intentions,” Campbell added, “and not realize you’re bringing bias that might negatively impact the person you’re talking to. In the fourth issue, that issue -- implicit bias -- becomes [really] important. Pornsak is attacking this subject from almost every angle you can imagine.”

Implicit bias became such a strong theme that it informed the creative collaboration as well as the story. Pichetshote told CBR, “I love working with Aaron [and Jose], because we really are a team and all weigh in on where the story is going. It was really important for me to write this without awareness of my own bias and then let Jose and Aaron check me on that. Like in issue #3, after I wrote the first draft, Jose came back and kind of checked me. It’s been a really great experience.”

To inform the conversations, the creators worked hard to ensure that their relationships reflect a diverse range of outlooks and behaviors. While Aisha gives people the benefit of the doubt, her Muslim best friend Medina is less forgiving of perceived slights. Boyfriend Tom steamrolls over Aisha’s budding friendship with his mother, taking an angry and aggressively protective stance toward the slightest disrespect. A suspicious neighbor is weighed down by a past experience that fills her with terror. The effect creates a complex sounding board for the way Aisha interacts with her community -- showing acceptance, senseless paranoia, and justified fear.

“We have this tendency to think about xenophobia, Islamophobia, racism, whatever it is, as this black and white monolith,” Pichetshote said. “But when we started this book, neo-Nazis were still the fringe. [Getting] into the areas of implicit bias, rather than explicit xenophobia and racism, is more interesting to me -- the degree to which all of us hold these things despite our best intentions. These things exist in people we call friends, and we want to explore that and interrogate that. Having the best intentions can lead you to [bad places]."

Expanding on those best intentions, Campbell explained, “When Tom is absent, Leslie and Aisha actually function quite well together, even though there’s a wall between them. Aisha has the type of humanity that enables her to bypass that and connect with Leslie. But then Tom comes around brings with him all of the emotional and societal baggage of being with somebody who is representative of a completely different culture. He inserts himself as a sort of apologist and makes everything worse. He’s the one that ratchets up the tension in the house, because he is so desperate for these two women to love each other and be able to exist together that he does the exact opposite. It’s indicative of what’s happening now with the inability to come together for so many people. You create these walls where you say this behavior is not acceptable and if you do this behavior for any reason whatsoever, that ends the debate completely and I don’t want to have anything to do with you.”

“As the ‘right thing’ evolves over time, people harm one another even with the best of intentions,” Pichetshote said. “If the same comment is said to me now, as compared to years ago, do I push back against it now? Am I being too sensitive to it? Am I hurting a global conversation? It all goes back to this confusion -- we’re so not used to thinking about it.”

Campbell expanded on the moving goalposts of acceptable social standards with a pop culture comparative. “I’ve been rewatching Friends recently and I can’t help but watch it through the lens of right now and think how the show, with this scripts, would never get made right now. It just wouldn’t happen. There’s so much that at the time was considered very progressive, very open, accepting and inclusive, which now would be considered offensive, topics that aren’t allowed in just twenty years from the beginning of that show.”

The creators worked hard to ensure that while Infidel draws on divisions in modern America to create its emotional resonance and terrifying underbelly, it never ever loses sight of being a horror story. Infidel is a ghost story, a haunted house story really, with truly unsettling designs and fonts to carry across the spectres’ deathly wails and undying rage.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='How the creative team came together, making a horror story reflective of modern times']

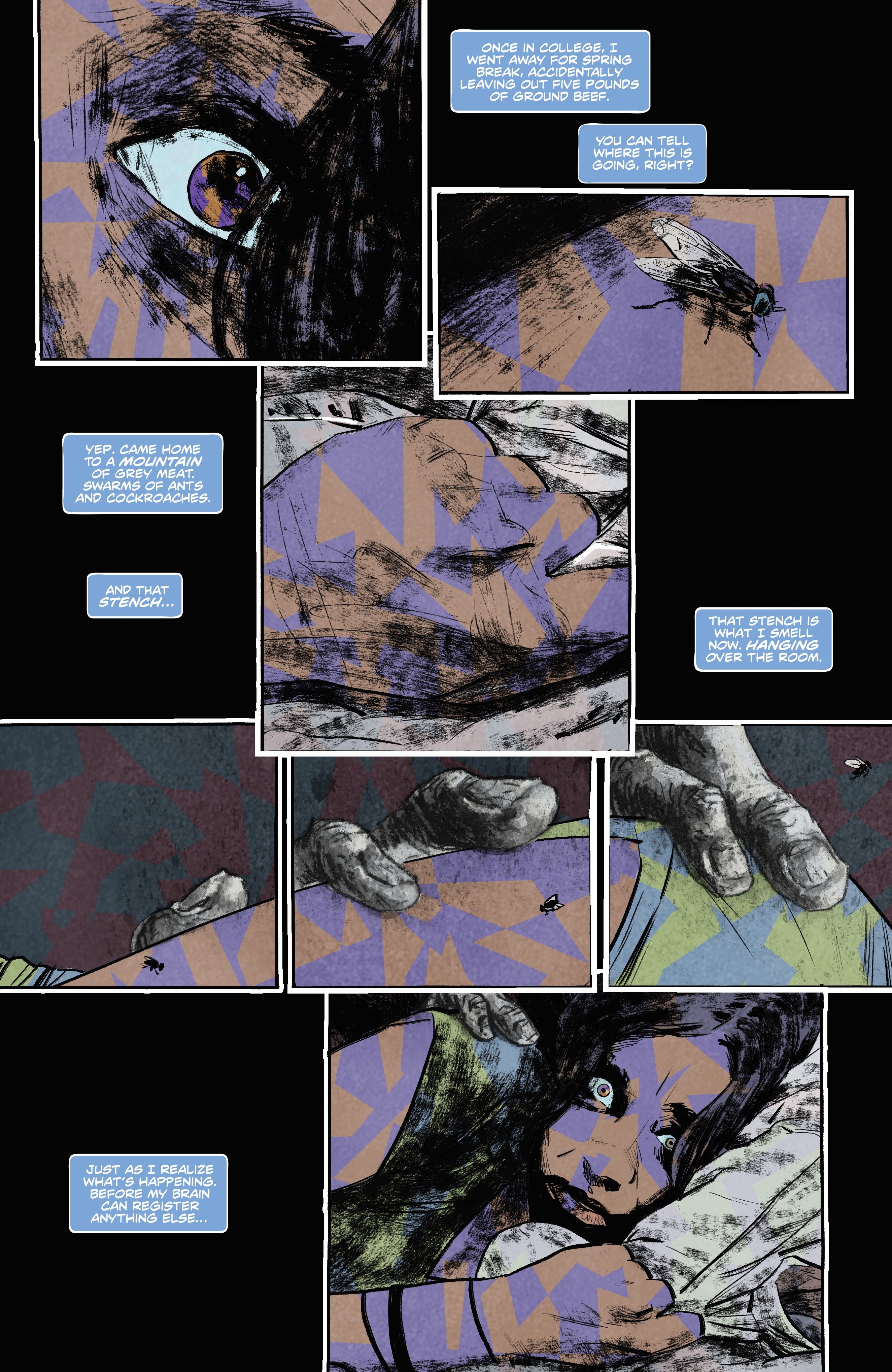

“Because I wanted to experiment with techniques, I decided that the ghosts -- anything spiritual or spectral -- is done traditionally. So it’s paint and wash and several mixed media techniques,” Campbell said, enjoying the chance to talk process. "Those pieces get layered in to the digital aspect, which is all of reality. All of our real world characters and settings are done digital, drawn on Cintiq. The line between the traditional technique and the digital technique represents that line between the old ways of thinking and the new ways of thinking that are at odds with each other.”

Pichetshote expanded on the ghosts, discussing how their presence ties concretely to the fears Aisha is facing. “Without getting into spoiler territory, we [feel] any sort of xenophobia isn’t black or white. It’s on a spectrum. This idea that anybody’s biases can become harmful or malevolent was very much on our minds. There’s a spectrum that exists and trying to figure out how people move along that spectrum is so much of what the story is interested in. When you start reading the first issue, it’s presented to be a very clear-cut thing. You have an American-Muslim woman in this building; you have things that seem to be anti-Islamic that are tormenting her based on the background of the building - but the intent of the book was always to keep going one step farther and to show how blurry the lines are. And how scary it is that those lines are so blurry.”

On the topic of assembling the creative team, Pichetshote says he first approached Villarubia with a game they’d often played when Pichetshote was an editor at Vertigo. “‘Hey, I’ve got this new book in and who do you think the artist should be? Here’s who I think the artist should be.’ Jose’s knowledge of comics is so broad. He can tell you about Adam Hughes’ Superman Meets Gen 13, and he’ll also tell you about this obscure French artist who just won the Angoulême. He knows so much about comics, so it’s great talking to him about different artists. And Jose actually came back and said that he’d love to edit this.”

Villarrubia confirmed. “Pornsak knew that for a long time, I have been a ‘closeted editor.’ I helped my friend Jae Lee with Hellshock two decades ago, suggesting plot twists, character names, the shape of the story… I have been doing this to different degrees since then for comics, theater and even some film projects. But always uncredited. Because Pornsak was my editor for years, and a very picky one at that, I knew that we could agree and disagree [without arguing]. That is important -- to get the best results you need to be perfectly honest with each other without the fear of insulting the other person.”

On selecting Campbell as the artist for Infidel, Villarrubia said, “I always wanted to color Aaron. We tried for a previous series, but it did not work out. I pretty much always knew how I would do it (not over-rendered [Laughs]), but I cannot edit my own colors. So Pornsak and Aaron are the ones who give me correction on the colors.”

Campbell had studied at Maryland Institute College of Art where Villarrubia teaches. Although Villarrubia never taught one of Campbell’s classes, the connection had led to a casual friendship over the years. “One day, out of the blue, he messaged me about this book,” Campbell said. “I’d been wanting to do a creator-owned project for my entire career, [but] I never had an opportunity. I was wrapping up my work on Felix Leiter when Jose messaged me. The timing was perfect because the initial stages of development -- from the eight-page pitch package to designing the ghosts, getting Pornsak’s final edits on issue #1 -- were done. One day I finished work on Felix Leiter, the next day I started on Infidel. We sent off our pitch to [Image Comics publisher] Eric Stephenson and he contacted us, what, within the hour?”

Laughing, Pichetshote confirmed. “It was kind of freaky. We had planned this whole six-month process of figuring out who wants Infidel, and Eric literally wrote an hour later and said, ‘Let’s do this.’”

Image stood out as the team’s first choice to publish Infidel, because, Pichetshote said, “I wanted to work with Jose as an editor, which makes it a lot trickier. And having made comics as an editor, I get so geekily jazzed about the minutia -- the idea that I can put out a book that doesn’t have to have ads if I don’t want it to, and I’ll know where every single page turn is -- that should not give me as much joy as it does. It gives me so much joy.”

“There were a couple important art decisions that were all about page turns,” Campbell added. “‘The big scare, the big splash, is on the right-hand side, so you don’t get that page turn. We need to add a page.’”

In the end, the creators just hope people like the book and are unsettled by the questions it poses. “The real intent here,” Pichetshote said, “was to make a horror story that’s a little more reflective of our times. Everyone on the team is a big horror fan, and we felt, especially now with all the remakes, that the horror genre feels a little trapped in amber. We are still living off the fears of the '70s and '80s. We wanted to try to bring out the unique stuff [that we’re scared of]. Part of that is me delving deep into my own fears. So much of this book comes from my fear of where we’re at in this moment and what happens next. And to try to be as honest as I can about the portrayals of the intent and the fear, to modernize it as much as possible with the idea that if you take something familiar and the moment we’re in, you’ll get something familiar and something fresh at the same time.”

RELATED: Image Announces Three New Titles: Infidel, Analog & Bingo Love

“As I’ve been working on this, I’m more and more realizing that people are coming to this project thinking that there’s a political agenda, and there isn’t,” Campbell said. “At its core, this is a horror story that is using a unique and polarizing aspect of our times as a setting, and using that setting to tell a compelling and terrifying story. If people put aside that notion that we’re putting forth this particular agenda and approach it with the idea that this is a horror story for our times, they’ll get much more out of it on a much more basic level.”

Pichetshote agreed with his partner that the story has to rule the day in Infidel: “We’re trying to be honest and truthful to the situations and the characters. Aaron’s 100 percent right that that’s definitely the guiding light. Stories fall apart when you try throw an agenda on.”

Infidel #1 is available now from Image Comics.