It's 2012, I'm 35 years old and I'm reading two new comic book series, both based on decades-old intellectual properties for which I had a great interest in, and rather intense feelings about, at different points in my childhood. This is in no way unusual: Every line of toys, every cartoon series or TV show, every movie I was into at some point in my childhood now exists as a comic book and, in most cases, rebooted toys, cartoons, TV shows and movies. For children of the 1970s and 1980s, our entertainment franchises have grown up with us.

What's slightly unusual about Battle Beasts and The Crow is how relatively obscure they are, compared to the Godzillas, Star Wars and G.I. Joes.

It's 1987, I'm 10 years old and I don't know it yet, but I'm reaching the end of the period in my life in which I can play with toys, in which I can easily slip into a time-stopped world of pure imagination and see characters appear and dramas unfold based on nothing more than some small piece of plastic, molded into He-Man or Boba Fett.

A friend comes over to play with me, and we divide our mixed lines of action figures — Transformers, Ghostbusters, Masters of the Universe, etc. — into teams that will build bases and battle one another. He has something new with him called "Battle Beasts."

They were little rubber anthropomorphic animal-men wearing high-tech armor and bearing weapons. One of his was a deer with a drill in place of his left hand. They were a bit bigger than M.U.S.C.L.E. guys, but much smaller than even Star Wars and G.I. Joe guys. Each one had a little heat-sensitive sticker on it its chest, and if you rubbed it, a symbol would appear — for either fire, water or wood.

As an animated television commercial would eventually explain to me, each beast belongs to some sort of team, and their chest symbols revealed which beast could best which beast. It was essentially like rock, paper, scissors: fire beat wood, water beat fire, wood beat water. (The first two made perfect sense to me, although I never quite got how wood beat water. In the commercial, they would just show a tree falling on the surface of some water and splashing — I guess the fact that it floated on water somehow defeated the water?)

Unlike most of the other action-figure lines of the 1980s, the Battle Beasts weren't accompanied by any cartoon — at least no one I ever saw — and so I didn't know their stories and characters the way I knew my G.I. Joes or Transformers. (In their country of origin, Battle Beasts were called BeastMorphers, but I was 10; I couldn't find Japan on a map, let alone know about its toy trends). They were just cool-looking monster guys.

It's 1994, and I've just turned 17. It's a Saturday night, and I'm lying on my bedroom floor, writing bad poetry in a spiral-ring notebook, or maybe drawing pictures of Batman or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on sheets of typing paper. The television is on for noise, and every single time a set of commercials comes on MTV, there's one for the upcoming movie The Crow; the targeted marketing was so intense that the TV practically hypnotized me into seeing it.

It didn't age all that well, but I loved it, and quickly sought out the trade-paperback collection of James O'Barr's original 1989 comics that inspired it, easily obtainable at the big box bookstore at the mall, thanks to the movie. I loved that even more.

Soon I would be drawing The Crow fighting Batman villain the Scarecrow. The sequel helped dampen my enthusiasm for the character and franchise — and each new film would dampen it further — but that movie and especially that comic were ideal experiences for a 17-year-old kid, and they introduced me to bands that would become favorites (Joy Division, The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Cure, etc.).

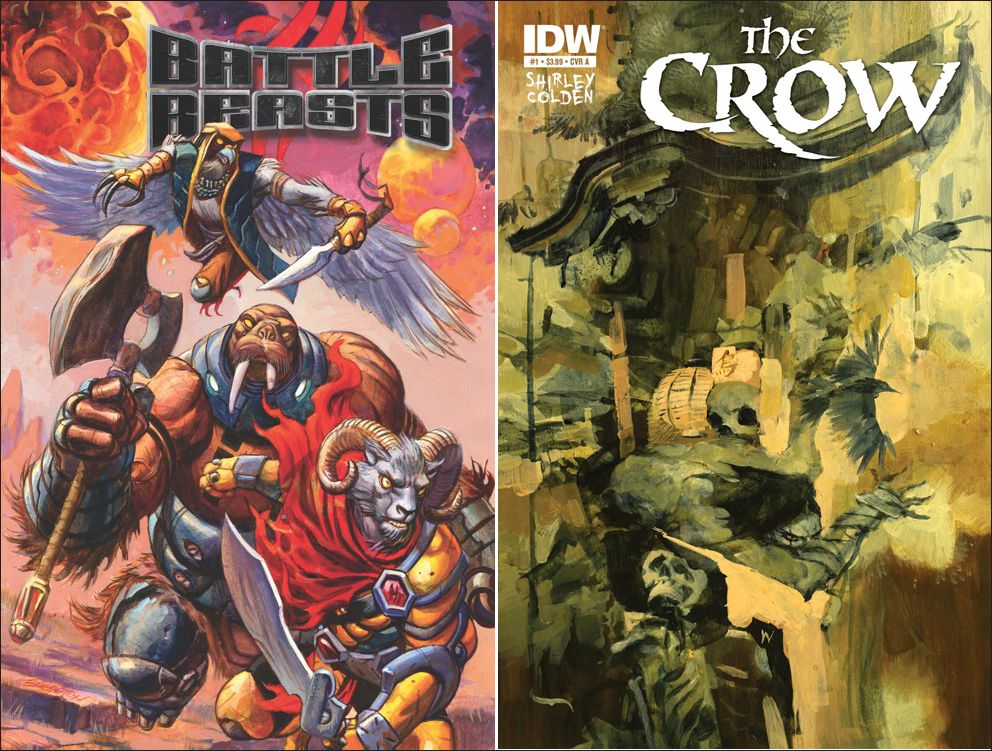

And it's 2012, I'm 35 and I'm reading Battle Beasts #1 and The Crow: Death and Rebirth #1.

Battle Beasts is a pretty solid first issue, introducing the characters and outlining some of the conflict while shifting the action from somewhere alien to somewhere readers can relate to.

Writer Bobby Curnow and artist Valerio Schiti introduce us to a trio of warrior animal-men — a bighorn sheep, a walrus and a bird guy — on a strange planet, with other planets visible hanging in the sky like moons. With the sheep guy doing the narrating. They are outcasts, conscientious objectors of some sort who refuse to fight in a senseless war the rest of their people are engaged in. That means, however, that they have to fight large groups of their own people pretty much constantly.

About halfway through, we're introduced to a Department of Defense linguist played, weirdly enough, by Zooey Deschanel, who is working to translate the directions to a Battle Beast artifact found on Earth. And then the Beasts invade Earth, and she and her brother are protected by the heroic trio from the first half of the book.

The plot reminded me a lot of Transformers (the Michael Bay movie version, not one from the cartoons or any of the comics, which IDW also publishes), with an alien war coming to Earth, and the outnumbered good guys siding with the attractive, twenty-something humans against all the bad guys. Only sans the Transformers trilogy's awful attempts at comedy.

It's difficult to declare a book a success or failure by its first issue alone, but this one left me interested enough to want to check out the next one, which is one of the more reliable metrics by which to judge serial comics. There's lots of cool and weird-looking animal-men during the Earth invasions scenes (a monkey-man wielding a sword with his prehensile tail, a goose-man, etc.), and they are all engaged in some form of battle, so that certainly meets the of the expectations engendered by the title.

I didn't recognize any of the characters from the toy line, and they all seemed to be outfitted like medieval or ancient Eastern warriors rather than the space-age soldier I remember from my childhood. But there were animal-men fighting each other and wrecking shit; I'm sure my 10-year-old self would have liked it well enough. Although he might have liked it if one of the many variant covers IDW published had a heat-sensitive sticker to reveal if this issue of the comic could defeat another issue of the comic.

As for The Crow #1, it has a higher bar to pass, as the nostalgia it's aiming to invoke is of more recent vintage, and it's based not on a goofy toy line, but on a classic of the black-and-white publishing boom, a comic (and film) aimed at adult audiences.

It too has a bunch of variant covers -- seven in all, I think -- including two that give it the look of a 1990s Vertigo offering, by Kent Williams and Ashley Wood, and two by O'Barr himself, although they seem to depict the original version of the character, rather than the one appearing in this story.

Perhaps wisely, the action is set in Japan, and the book is therefore distancing itself from the original comic, the original film and much of the previous extrapolations of them rather immediately and forcefully.

Writer John Shirley hasn't just changed the location of the story, however, but the nature of the basic Crow formula of "murdered lover is resurrected to avenge his soul mate." The nature of the woman's death is old-school B-movie bizarre, and involves the upper echelons of a bio-medical corporation transplanting the brains or minds into dying, elderly members into the bodies of young and beautiful victims.

The new Crow's lover is still murdered, and, after he himself is, he still wants to avenge her, but now the bad guy is in her still-living body and ... well, it' s a departure, which is welcome, but it's such a departure, that it seems like it may have been too much of one.

It's a little more difficult to tell where this is going, as the title character doesn't appear until the last panel of the last page — the rest of the issue is devoted to unconvincingly depicting the gaijin soon-to-be-Crow and his Japanese fiancee as a lovers with a bond stronger than death and the brain-transplant plot.

What worked best about the original Crow narratives, for me anyway, was the more or less random, this-could-happen-to-anyone nature of the crimes, and the sense of frustration that the victims must have felt given those circumstances. This is something else entirely, and I think it loses the emotional impact in the sci-fi nature of the plotting.

That said, this is something like the 15th telling of the tale, so one can't blame the creators for trying something different, whether it ultimately works or not.

Kevin Colden's artwork goes a long way towards helping it work; his highly expressionistic work and somewhat stylized character design occasionally evoking a little bit of a young Sam Kieth's work. It might have worked better still in black and white, however, given both the source material and the country in which its set, a place where most the comics that come from there and end up here are also black and white.

But it's 2012 and I'm 35, and it's also 1987 and 1994, and I'm 10 and 17, and it always will be and I always will be, and that's one nice — if strange — thing about comics, and the modern entertainment industry in general.