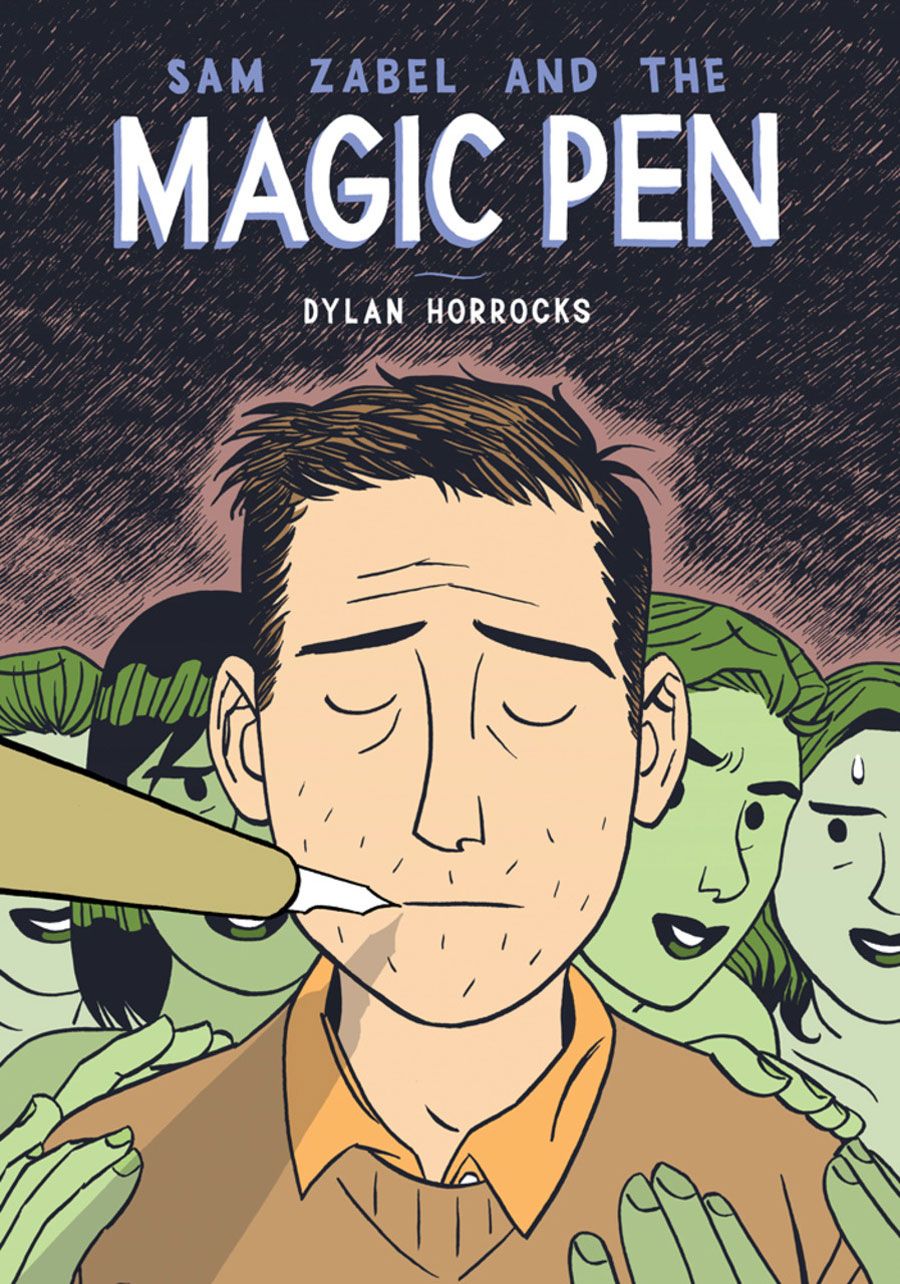

Since its publication in 1998, Dylan Horrock's "Hicksville" has been lauded as both a great graphic novel and an iconic book about comics. In "Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen," Horrocks promotes one of the central characters in "Hicksville" to title character status.

5-STAR REVIEW: "Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen" is "Highly Recommended"

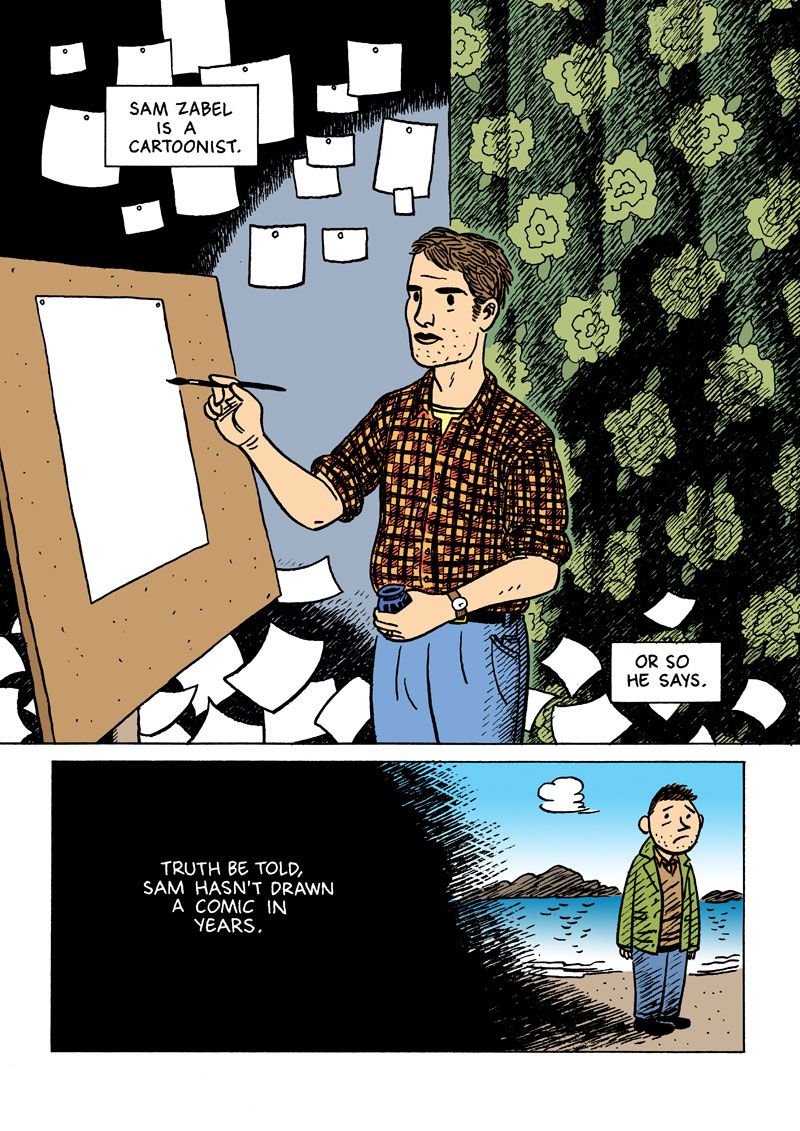

At the beginning of the Fantagraphics-published book, Zabel is suffering from depression and writers block -- much as Horrocks himself was even while he was scripting DC Comics' "Batgirl" series. The book explores what happens when Sam finds a magic pen and examines a variety of fantasies -- his own and other people's -- in a story that's fun, but ultimately reaffirms the importance of fantasy and escape in our lives. "Sam Zabel" is funny and thoughtful, moving and beautiful, and much like Horrocks' first book, is a thoughtful meditation on the comics form.

CBR News: Where did "Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen" start?

Dylan Horrocks: I started work on the book about ten years ago. I was still working for DC Comics writing "Batgirl," and I was going through a pretty tough period in terms of my own work. I was struggling to get anything written or drawn and when I was writing for DC, I was writing stories that weren't really me. They weren't coming from my own imaginary landscapes. I was writing characters and worlds and stories that came from other people's imaginary landscapes. I also felt like my own writing voice wasn't suitable for those stories so I found myself adopting a voice that wasn't really true to me. It was as though I lost my own voice as a writer and a cartoonist and lost the ability to tell the stories that came from me.

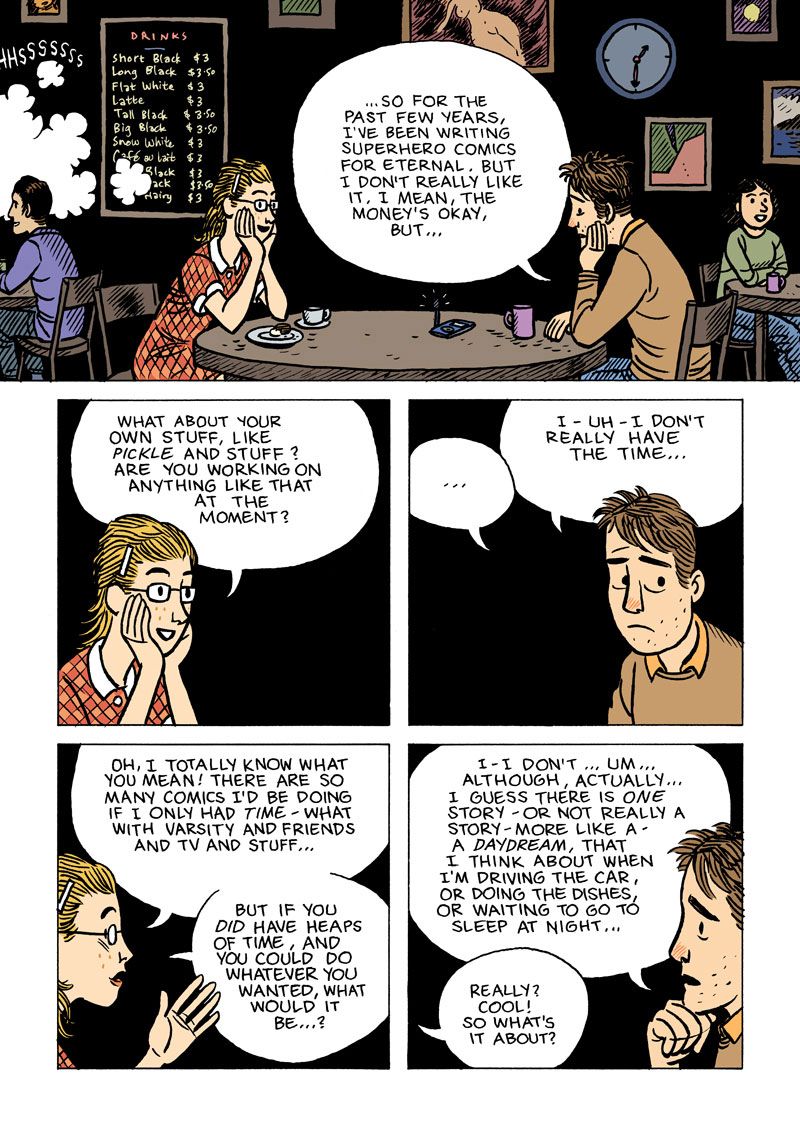

"Sam Zabel" started as a daydream which I would indulge in while I was driving the car or lying in bed waiting to go to sleep. It was an escape from all the stories I was thinking about all the time for "Batgirl" and the other projects I was supposedly working on but was struggling to get done. "The Magic Pen" daydream was detached from all of those stories. I didn't intend for it originally to turn into a comic. It was just a daydream.

One day, I was talking to my sister who is a filmmaker. She was deep in development hell on a film she was working on, and we were at a playground with our kids. Inevitably, we ended up talking about the nightmares we were both going through with our work. [Laughs] We got to talking about writers block. I had been trying to find books by writers about struggling with stories -- not struggling with writing, but struggling with their relationship to story. Because through all of this, I had started to distrust stories and art. A friend of mine called it a crisis of faith that I was going through -- a crisis of faith in story, rather than in religion. My sister said that a lot of writers don't like to write about this stuff because there's almost a superstitious fear that by writing about it you'll bring it on and won't be able to write any more. [Laughs] She told me I should write about what I was going through and so I did. That was how "The Magic Pen" actually started being put on paper. That's why it opens with Sam struggling with all of these issues and feeling very stuck. Then I allowed the daydream that I'd been having to take over and at that point, all bets were off. [Laughs]

Did you know from the beginning that it would be about Sam?

The very beginning of the daydream actually involved Sam being put in a situation of absolute power. [Laughs] It involved Sam Zabel and Dick Burger, from "Hicksville," stranded in the middle of nowhere on two islands. The locals, who had never seen people from off the island before, decided that each was the god king of the island and they could do whatever they liked. I was interested in seeing how these two very different characters would make use of that situation in different ways. At some point, that morphed into Sam being on Mars.

There is that great moment where Sam is on Mars and he says he's a cartoonist and all the Martians bow down.

A little bit of wish fulfillment. [Laughs]

This idea of fantasy and how we escape is at heart of the book.

The book becomes a story about fantasy and our relationship to it. It approaches that question from a variety of different angles. It asks a series of questions about fantasy. At the beginning, fantasy is explored as escape. I'll try to avoid any egregious spoilers, but in the earliest stages of the story Sam escapes from his writer's block and his despair and depression by looking at these 19th Century genre paintings online. It's like escaping into a perfect world, into an arcadia -- with an erotic tinge to it. Later, he finds himself inside a comic book; he's accidentally escaped into someone else's escape fantasy and he has to navigate that. That begins to raise the question of whether fantasies have a moral dimension;whether it matters what we do in fantasies and what shape those fantasies take.

When I was writing superhero comics for DC, I was thinking a lot about power fantasies and wish fulfillment fantasies as they were expressed in superhero comics. Especially the very dark, violent Gotham City-based superhero comics. I started to feel that fantasies aren't always benign. Maybe some fantasies can feed parts of ourselves that can take us down destructive paths -- not necessarily just individually, but also as a society. There was a moment when I received a parcel of contributor's copies of an issue of "Batgirl" that I had written and on the back cover was a recruiting advertisement for the U.S. Army. This was around the time that the U.S. Army was using white phosphorous on civilians in Fallujah. I started to feel as though the vision of the world and of how you solve problems in the world that formed the bedrock of the Batman comics that I was writing was in some ways related to the fantasies about how the world works that helped drive the public acceptance of the invasion of Iraq. It's not that I had any clear opinions or answers about it, but I had a lot of questions. More than anything, "The Magic Pen" is my way of trying to explore those questions.

Sam seems to start out skeptical about fantasy and story and by the end he has a more complex relationship to it and understanding that it can serve an important function.

In a way, I was trying to find my way back to what I had always loved about fantasy. I feel as though the process of drawing the book restored fantasy to me as a thing I can wholeheartedly enjoy -- and also use for all sorts of positive things -- while also having a deeper understanding for myself of the complications of fantasy. I'm interested in fantasy in all sorts of forms. The epic fantasy genre -- Tolkien and all the rest -- has always been my favorite genre as a reader. I'm kind of obsessed with the fantasy genre, but I'm dissatisfied with 95% of fantasy novels that I try to read. I've long had a really complicated relationship with the fantasy genre. I've also been obsessed with fantasy roleplaying since I was thirteen. It really is my other great lifelong obsession other than comics. Fantasy roleplaying games are all about creating an imaginary world and then going there and exploring it and making it as real as possible. All of that is playing into these questions that I was asking in "The Magic Pen," but I'm also really interested in erotic fantasy and the very complicated place it has in our culture and our own personal lives.

At one point, a character says in the book, "there's a dark side to fantasy. Not all dreams are dreams of liberation, pleasure or joy. There are fantasies of purification and destruction, hatred and revenge." You could argue that fascism is essentially a political fantasy. I think you could say the same of Leninist Communism as well. Part of what I'm interested in is that relationship between our fantasies, our daydreams, our stories, and the real world that we're living in. It's a two-way relationship and there's no way of avoiding that relationship. Fantasies are very central to how we function as human beings and certainly how we function as a society. I feel as though our ways of talking about that relationship are often very simplistic. I just wanted to muddy it up and look at the complicated stuff that started to emerge and rise to the surface when I muddied the waters.

You open the book with two quotations by William Butler Yeats and Nina Hartley.

Yes, the poet and the porn star.

The point of Hartley's quote is that our actions have morality, our intentions have morality, but our fantasies do not.

She has a lovely way of putting it, that they have no moral weight.

I loved that phrase, and yet as Yeats gets at, how we do one thing is connected with how we do all things.

Those two quotes feel equally true to me -- and yet they contradict each other. Yeats and Hartley are arguing with each other. I wanted to open the book that way to set up a dialogue between those two positions and then see what that discussion would generate. In the book, every time I create a situation which seems to confirm one or the other, I always wanted to muddy the waters again to make sure that the other position would have something to say about that situation as well. There are various situations where Sam or another character may be making moral judgements about a particular fantasy that they find themselves inside, but while they're doing that, the drawings are making sure that we get a chance to enjoy the pleasures of that fantasy at the same time. I feel like it's very dishonest to moralize about something while denying that it has a visceral effect on us. Maybe the visceral effect is, in and of itself, of sufficient value that it overrides the moral concern? Maybe that's a valid position to take. I just wanted to make sure that the conversation kept going and always opened up new angles in the discussion.

This is a very serious conversation we're having. The book was also meant to be a lot of fun. [Laughs]

I wouldn't say that it's a lighthearted book, but your approach is lighthearted. It's easy to read, but there is so much going on.

That's what I wanted to do. I want the book to be serious, but also fun and pleasurable. I didn't want to just talk about fantasy, I wanted to indulge in it as well. I feel like it's a very indulgent book. Even the very serious discussion throughout the book about fantasy -- some of which is stated and a lot of which is implied -- is indulgent because I enjoy doing it. My wife has always joked that on my tombstone it will say, "It's more complicated than that." It doesn't matter what we're talking about, at a certain point I will always say, "I think it's a bit more complicated than that." Throughout the story, that's what I'm basically doing. It was also just a chance to indulge in all kinds of crazy escapist fantasies -- and to celebrate them, too.

I'm very interested in stories and fantasies which at a certain point became unsavory -- either for moral reasons or political reasons -- and yet, the fantasy itself is rich and complicated and served all sorts of purposes. Those fantasies clearly serve desires, fantasies, needs and fears which often go deeper than the superficial aspects of the fantasy which have since become unacceptable. I think epic fantasy is a really interesting example because a lot of what's underlying the tropes that are common in epic fantasy are very familiar from 19th Century and early 20th Century adventure stories. You can see that very clearly in the use of races in fantasy fiction. The races in fantasy on one level simply adopt all the incredibly racist stereotypes that were common in colonial adventure stories; for example, orcs and goblins often take the role previously played by African or Arab savages. They're described in the same terms. The same adjectives are used. Tolkien again and again calls the orcs "swarthy," for example. The behaviors that they exhibit are the behaviors of the Victorian idea of savages. But it's acceptable for us to treat them as a race almost deserving of extermination in modern fantasy literature because they aren't human. We're not talking about black people, we're talking about orcs -- and yet, it's the same set of tropes. It's the same narrative. It's the same fantasy of the other as the savage.

In saying that, I'm not condemning fantasy as some kind of racist ku klux klan fantasy. What intrigues me is that we still want to have those tropes. I'm interested in what purposes they serve beyond the continuation of racist ideas of "the other." I think there's more to it. Orientalism is partly a package of racist ways of looking at the relationship between Europeans and Arabs, but it's also a purely European wish fulfillment fantasy. Europeans desired a certain imaginary landscape into which they could escape and then they projected that onto the Arab world. Projecting it onto the Arab world is a destructive, colonialist thing to do, but the fantasy itself that was constructed in the first place is really interesting and may contain all sorts of things that are quite important to us culturally. Maybe they're inherently terrible and destructive and we need to purge them from our culture, but I'm not so sure. I think epic fantasy -- and to a lesser extent science fiction -- has become one of the main genres into which we've transported the parts of those fantasies that we want to keep. Often we try to detach the political and moral problems that we're now aware of with Orientalism, but we still want the pleasure of it. I explore that in "The Magic Pen." It's not explicitly spelled out, but that was in my mind when I was constructing the Mars and Venus sections of the book.

As you were talking about that, I thought of the Lady Night section, where she explains her origin and its meaning, which as you would say, is more complicated than Sam thought. I kept thinking about Wonder Woman, who was a very radical and complicated character, but has become less interesting and more of a power fantasy.

I feel as though people want a very simple narrative about a character or a story or a fantasy. They want to have the things that they identify as good about the story without the stuff that they feel uncomfortable about -- but it's all bound together. When a character or a story is really rich and potent, the reason is partly because it touches a lot of stuff that goes quite deep.

I have a very difficult relationship with Batman, having written Batman and so having to engage with him much more intensely than I otherwise would. I just don't like Batman. He's a character that I find really disturbing on a lot of levels. When I was writing "Batgirl," I was very conscious of thinking that Batman expressed values that were very contrary to mine, that ultimately he was a destructive presence in the culture. I feel like he wasn't doing anything good. As I've gained more distance from him because I haven't had to write him, I've been able to recognize that it's more complicated than that. [Laughs] There's all sorts of layers to the role that Batman plays in our culture. Some of them I can feel more positive about, but even if he were purely a destructive presence, maybe that's worth having. I mean, he's not real. [Laughs]

I would definitely write "Batgirl" very differently today than the way I wrote it then. It would be a story explicitly about violence. About the way we construct our ideas about violence, the effects that it has on people, and about both the reality of crime and the myths that we construct about crime. I feel Batman is a very potent myth that we construct about crime. It expresses a very powerful -- and not necessarily honest -- story that we carry around about the relationship between crime and cities and drugs and poverty and power and the state. Some people have explored that quite explicitly and quite intelligently, but I shied away from it when I was writing "Batgirl." I don't like violence. I don't find it exciting. I don't find it appealing. It doesn't speak to me as a power fantasy that I have any desire to indulge. Instead, it speaks to me as a very destructive fantasy. I really don't enjoy violence -- even silly, playful violence in action movies. It disturbs me. It was hard writing a Gotham City comic. [Laughs] My sense of it at the time was that those comics partly indulge our pleasure in stories of violence and I just don't feel that pleasure. If I was writing it now, I would write precisely about what makes me uncomfortable about it.

This is your second graphic novel after "Hicksville," which has become sort of iconic.

It's great that "Hicksville" has been received so well. One of the great joys and satisfactions of my life is knowing that "Hicksville" really means something to people. It's not just that I told a story that people had fun with. Even now, I get emails from total strangers telling me that Hicksville had a really big impact on their lives. That's an extraordinary feeling, and quite humbling, but I don't feel like I can take credit for whatever impact it's had on people. It didn't feel entirely like something I made up. The core elements of that story felt like they emerged and I happened to pick them up. In some ways, it's a terrible book. [Laughs] But it may be that it will always be known as my best book. It's acquired a status that's more than I could have ever hoped. Every so often people send me their PhD thesis about it. I mean, I was just making this shit up! [Laughs]

When I first started working on a book after "Hicksville," I felt like I had to do something that was simultaneously whimsical and enjoyable, but also had some great literary weight and significance. I don't think anyone can write a decent book under that kind of expectation. [Laughs] I did go in circles for a while. The first book I started was "Atlas" and I started serializing that as a comic book through Drawn and Quarterly. I kept going in circles. I kept changing the overall vision of the book. My conception of who the central character and narrator was changed between issue 1 and 2. I thought, well, I'll just fix it all when I put it together for the book. I was trying to put so much into that story that it became bloated and it could no longer breathe or move. I started doing "The Magic Pen" as a backup story that would be episodic and much more relaxed. I could have fun with it. That's actually how "Hicksville" started, as well. "Hicksville" was the backup story in "Pickle." The main serial was "Cafe Underground," which was the first graphic novel I planned. I fully scripted that and then slowly started drawing it. I started "Hicksville" to have a story where I didn't know where it was going. I just knew the landscape I wanted to explore. So I started that as a backup story and then it grew and started to take over the comic and began to subsume all the other stories in "Pickle" and finally became the first book I ever finished.

We've had this very heavy conversation, but the feeling of telling the story being pleasurable and telling a pleasurable story really comes through.

When I was in the worst of my creative block, I didn't enjoy drawing or telling stories. I felt like I had to do them, and they had to be done well enough to impress everybody. I kept trying to draw like other people. The first issue of "Atlas" was me trying to draw like the European cartoonists I was obsessed with at the time because I was very conscious of my drawing being inadequate. For God's sake -- I was being published by Drawn and Quarterly! I was on the same list as Julie Doucet and Seth and these other heroes of mine. It was very intimidating. Add to that the whole second book syndrome; I was giving myself such a hard time. At a certain point, it was painful to draw. It was really painful because I was so conscious of how badly I was doing it. After a couple years of that I got to the point where I felt like, drawing used to make me happy, telling stories used to make me happy. I used to enjoy it. I decided that I had to draw just for myself. I started doing a lot of sketchbook stuff. I did a couple of stories just for the pleasure of it.

I think for me the turning point was realizing that I couldn't actually draw like other people. There were all these other people I wished I could draw like but I just couldn't pull it off. Drawing is too physical. It's like singing. You can train your voice and you can exercise it, but you can't change it to someone else's voice. I feel that way about drawing. My drawing is innately awkward. I'm not a natural draftsman in the way that someone like Craig Thompson is. I've always struggled to draw. I realized I can't draw like other people, but there's no one else in the world who can draw quite like I do either. Drawing is so personal, it's like handwriting. I went back to using the same drawing tools I used when I did "Hicksville," which is felt tip pens. I went back to drawing on crappy cartridge paper and it was very liberating. I found myself drawing with pleasure again.

By the time I finished "The Magic Pen," I felt that the key was walking away from other people's expectations -- or my perception of what other people's expectations would be -- and deciding that I was going to do it for the pleasure of doing. That's something Lynda Barry talks about all the time, dipping your brush into the ink, moving it along the paper, and focusing on the physical pleasure of moving that brush across the paper and watching the ink trail along behind it. The goal isn't to produce a beautiful picture that other people will be impressed by; instead the goal is to have that experience of moving the brush along the paper. Once I got to that, drawing became like meditation -- and ultimately almost like a prayer to the world. I'm enjoying making comics more now than I have ever in my whole life. It's just sheer joy.