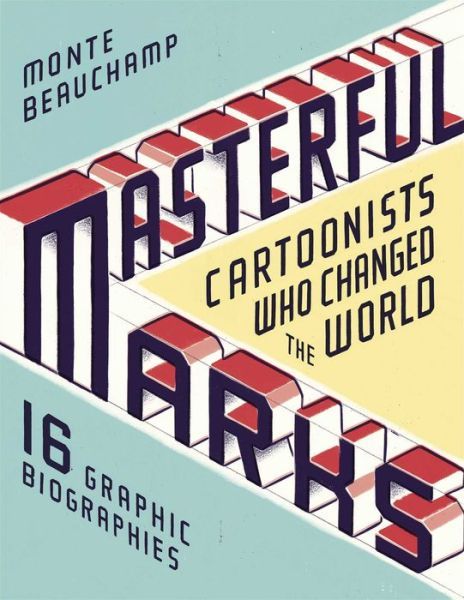

Blab founder and editor Monte Beauchamp's latest book, Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed the World, bears a subtitle that begs to be parsed, almost as much as it begs to be read.

He's gathered a Murderers' Row of great contributors and collaborators to tell the life’s stories of 16 cartoonists, in the most obvious format to do so — comics, of course.

But what, exactly, constitutes a cartoonist? Some of those included might have worked at one point in the field, but made their greatest marks in other areas: people like Walt Disney, Theodor “Dr. Seuss” Geisel and Hugh Hefner (whose inclusion will likely be the biggest surprise to more readers; and, make no mistake, the book is made as much for the casual reader as the expert, armchair or otherwise). Others you might not think of as cartoonists at all, like Edward Gorey or Al Hirschfeld.

And changing the world — the whole world?! — is a pretty bold claim, certainly bolder than changing, say, a genre, or a medium or an industry. Certainly Disney and Osamu Tezuka qualify, as do Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who introduced the superhero as we know it, and Jack Kirby, who reimagined the superhero, made countless contributions to the form and who created or co-created characters and concepts that today make billions of dollars.

But what about Harvey Kurtzman, Robert Crumb and the aforementioned Hirschfeld? Are their influences and innovations on equal footing?

Then, of course, there’s the matter that always arises in any such attempt: Who’s in and who’s not? Do those in deserve to be there more than some of those who aren’t? Why Winsor McCay instead of E.C. Segar or George Herriman? Why Charles Schulz instead of Walt Kelly?

And hey, why is everyone a white man of European descent, with the sole exception of Osamu Tezuka (who's nevertheless still a man)?

These are the conversations a book like this is all but guarantees to elicit. Hell, it’s actually part of the fun of such a work.

But it’s important to note that putting forth arguments, or establishing an exclusive stable of great, influential cartoonists, isn’t Beauchamp’s goal here, either stated (in his introduction) or implied (from the material that follows). Whatever quibbles readers might have about elements of the book, the subjects of all 16 entries are unquestionably masters of their respective fields, and all are more than deserving of having their stories told and even championed.

In that introduction, Beauchamp states that the book started with an attempt to answer the question, “Who were the original comic artists that left an indelible mark upon the world, paving the way for those who followed?" From there, he assembled various aspects of “cartoon genres" -- comic strips, animation, picture books, etc. -- and trying to identify the figures who most influenced or revolutionized those categories.

The resulting stories, four of which Beauchamp collaborated with others to tell, are as different from one another as the men they’re about, although most try to tell their biographies using a style at least evocative of that of their subjects, cross-referencing the work verbally and visually in the narrative.

Each is a rather strong work, which shouldn’t come as any great surprise, given the fact that cartoonists like Peter Kuper, Drew Friedman, Frank Stack, Gary Dumm, Denis Kitchen and Dan Zettwoch are involved.

Beauchamp and Ryan Heshka’s Siegel and Shuster story leads off the book, and it’s a pretty depressing read. The central characters are first seen hunched over, holding their heads in “the depths of despair," and their final appearance is as sad and worried-looking ghosts, tucked under the arms of their famous creation, who flies them off into immortality. Drawn in a warm, bright style that looks like a storybook version of the Fleischer Studios Superman cartoons, the imagery contrasts sharply with the subject matter, one of the more tragic — and potent — stories in American comics.

That’s followed immediately by Mark Alan Stamaty’s Jack Kirby tale, which fills its pages with bodies in exaggerated, in-your-face motion, a deluge of emotive lettering, and propulsive panel borders. Stamaty doesn’t draw much like Kirby, but I’ll be damned if he didn’t distill a bit of the legendary artist's lightning-bolt energy into a pastiche that nevertheless maintains his own particular style.

Nora Krug goes in the opposite direction with her story of Herge -- which couldn’t be further removed from the subject’s stately, perfectly composed, even images -- with loose, rough character designs, bright, sickly colors and a general alt-comics aesthetic (Tintin and Snowy appear but once, the former from the knees down, the latter from the collar down).

Masterful caricaturist Drew Friedman draws “R.Crumb and Me,” folding the seminal counter-culture cartoonist’s story into one that his own life occasionally intersects with, his photorealistic-plus style perfectly capturing the real people featured, making them look as big and exaggerated as any comics characters.

Peter Kuper likewise appears in the Harvey Kurtzman entry “ Corpse on the Imjin!” as the subject interrupts Kuper’s story with a “Hey — Schmendrick!” and then walks Kuper's comics avatar through much of it.

My favorites are probably Dan Zettwoch’s Osamu Tezuka and Denis Kitchen’s Dr. Seuss (both of which rely heavily on the characters and iconography of the subjects’ extensive works), and Beauchamp and Gary Dumm’s Hefner bio, in large part because so much of it was new information to me (and because Hefner’s story is also the one of many other great cartoonists) and Marc Rosenthal’s Charles Addams … although Rosenthal has the advantage of having one of the most natural subjects for a comic strip imaginable. Even among this crowd Addams’ life stands out as particularly, almost unbelievably, perfect, in a you-can’t-make-this-stuff-up kind of way.

I was much less impressed with Sergio Ruzzier’s Schulz biography, which casts the artist as a weird, sad little bird-like creature, and Beauchamp and Larry Day’s Disney biography, which is quite oddly told, with an anthropomorphic chicken walking alongside a chick, telling him about Walt Disney in a 60-panel, six-page info dump of dialogue. The artwork is lovely, and perhaps concerns about litigation led to this particular form, but it stands out as particularly dull compared to the other 15 stories.

There’s also Winsor McCay by Nicolas Debon, Al Hirschfeld by Arnold Roth, Lynd Kendall Ward by Beauchamp and Owen Smith, Rodolphe Topffer by Frank Stack, and Edward Gorey by Greg Clarke.

That's a lot of great cartoonists telling the stories of a lot of the greatest cartoonists, then. The conversations the book is likely to spark? That's just a bonus.