by John Lees (check out John's column, Comic Book Club, at ProjectFanboy here)

Okay, so who reads Scalped? For those of you unfamiliar with the series, Scalped is a sprawling crime drama by writer Jason Aaron and (for the most part) artist R.M. Guera, published by DC Comics’ celebrated Vertigo imprint. Set on the Prairie Rose Indian Reservation in South Dakota, it tells the story of Dashiell Bad Horse, a prodigal son returning to his childhood home and falling under the sway of community leader turned gangster Chief Red Crow. The comic has been widely met with critical acclaim, not least from here at Comic Book Resources. As well as regularly reviewing the book, CBR has prominently featured Scalped right here on the Comics Should Be Good blog. The comic is a constant fixture on What I Bought by Greg Burgas, who offers plenty of insightful commentary on the developing narrative. Brian Cronin, meanwhile, devoted an entire week of 2009’s Year of Cool Comic Book Moments to Scalped. CBR ranked the series at #5 in its Best of 2009 list. Looking beyond this site, Jerome Maida of the Philadelphia Daily News not only ranked Scalped as the best comic of 2009, but as one of the greatest comics of all time.

But the response to the book has not been universally positive. Some detractors have accused the comic of

perpetuating negative Native American stereotypes, even going so far as to condemn those who praise Scalped as part of the problem. As readers of Scalped, are we guilty of promoting racism? Well first, I would suggest arguing on these lines takes us up a blind alley where we don’t look too closely into the facts and simply accept that Scalped and its author are racist, knowingly or otherwise. So I am going to take things back a notch, and ask: is Scalped really racist?

To answer this question, we need to take a closer look at Scalped, and see how the comic itself holds up against such accusations. The most common complaint is the idea that the comic portrays all Native Americans as criminals and lowlifes. While yes, there are violent characters in Scalped and many laws are broken, this is a crime story, and is therefore by its very definition going to focus on criminals. But it should also be noted that thoroughly decent, law-abiding Native characters such as Granny Poor Bear and Franklin Falls Down challenge the notion that the book presents all Indians as scum, while the very worst figures in the book, those most devoid of redeeming qualities – such as psychotic killer Diesel or the amoral, vindictive FBI agent Nitz – are white.

One line of criticism I have encountered demanded more balance, that for every Native American engaging in crime or wallowing in drunken despair we should see another doing good for the local community or enjoying a happy and contented life on The Rez. This to me seemed like an odd request, not only because it would be utterly incongruent with the somber tone established in this particular comic, but because it clashes with the very dynamics of the genre as a whole. Should a comedy have balance by having half its content be harrowing drama? Should a horror have balance with extended sequences devoid of any suspense or peril? Why should the crime genre not be too much about crime? Perhaps, as I shall touch on later, it is more to do with the color of the characters committing the crimes.

I think part of the problem could be that much of this criticism is based on the first few issues of Scalped, or on the first graphic novel collecting the series: Indian Country. In these early chapters, the focus seems to be less on character than action, and while I wouldn’t necessarily say the characters are presented as racial stereotypes, one could see them as noir archetypes: the outsider, the gangster, the wise old drunk, the femme fatale. While there were some glimpses of the depth that was to come – take, for example, the series of near-misses and miscommunications that prevent Gina Bad Horse from getting in touch with her son in issue #4, which in the next issue are given tragic significance - in its beginning, the series felt more like a conventional crime thriller, well told. I’d argue that it was with the collection of issues contained in the second graphic novel, Casino Boogie, that Jason Aaron really began to stretch his wings and the book’s unique voice was truly established. From this point on, the intricate experimentation with time and chronological structure made Scalped less about constant action than dwelling on a single moment, reflecting on it from different perspectives and examining its causes and consequences. Characterization came to the forefront, and those archetypes began to get a lot more complicated, turning into nuanced, multi-faceted individuals. As a result, critiques based solely on the first handful of issues don’t just seem outdated, but rather it’s like they miss the point of Scalped entirely, almost as if they were talking about a different comic.

As an example of this, one character that has been a target of particular scorn is Lincoln Red Crow. Based on his first appearance in the first issue, it might be easy to dismiss him as a one-note caricature, just a typical gangster heavy. In his first appearance, he has just finished scalping some unknown victim, so it is perhaps understandable to assume the character is to become a stereotypical Indian villain. But as the series develops, Red Crow evolves into a fascinating, tragic figure. Red Crow’s soul has been steadily eroded by the moral compromises and Faustian pacts he has made to open his casino. Driven by a desire to bring prosperity to the struggling Oglala Lakota tribe, this casino for him represents these lifelong dreams becoming a reality.

After decades of fighting to secure his people’s future, he has succeeded, but at the cost of becoming the very thing he hates the most. “You done spent too long playin’ the part a’ the poor, old pissed-off ‘skin who wouldn’t be caught dead workin’ for the man,” sneers one associate, “Cause now you are the man, and you don’t know what the hell to do with yourself.”

But still, some would continue to disregard this complexity, concluding that the book’s readers will only view him as a “savage Indian” or a “greedy Indian”. Not only is this an inaccurate appraisal of Red Crow’s story – classic themes like “the loss of idealism” and “power corrupts” are universal, not exclusively Indian - but it severely underestimates the intelligence and morality of the comic’s readers, assuming they must all be as racist as its author is imagined to be. What is the more likely scenario? That deep down, all readers of Scalped secretly hate Indians, and they were attracted to a comic with Native criminals through an insatiable desire to validate their own bigotry? Or that readers of Scalped just happen to like strong storytelling and compelling characters?

Red Crow is a mass of contradictions, with Aaron encouraging the reader to alternatively view him as a tragic hero, a monster, an optimist, a tyrant, a loving father, an abusive father, a mentor, a traitor, courageous, cowardly, spiritual, violent, a man on a downward spiral of despair. But these racially-charged arguments against the book can only see Red Crow as an Indian, with all these other aspects of his character becoming secondary, simply ways of commenting on him as an Indian. In this line of thought, it seems a white criminal can be a fully-fledged character in his own right, but an Indian criminal must be seen as a representation of all Indians. Who then, out of Aaron and his detractors, is more racially progressive?

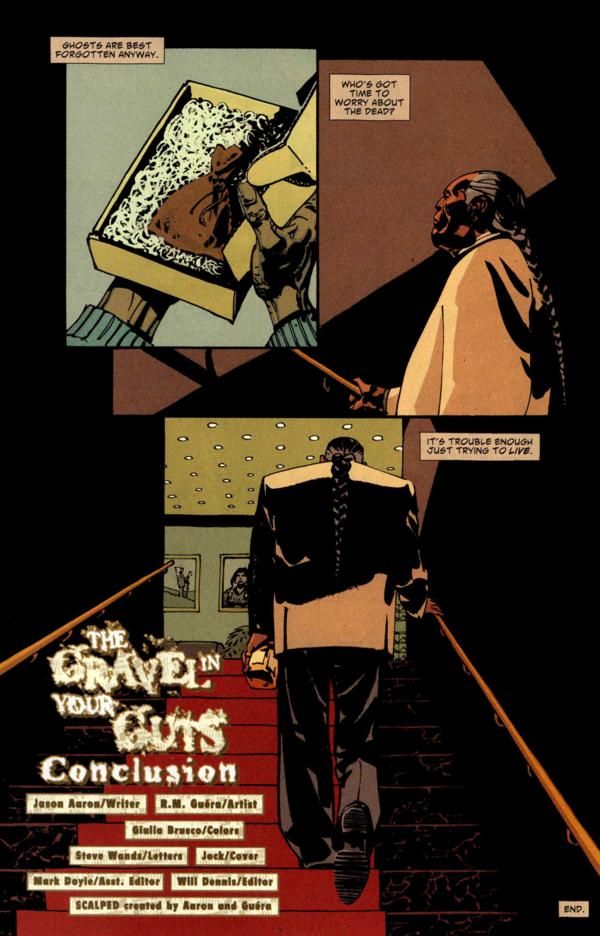

Here is a scene featuring Red Crow from the conclusion of a 2009 storyline...

It has been said that the reader generates just as much meaning from a text as a writer does, and as such no matter how fair and nuanced writers become in their depictions of Natives, the possibility of someone (over)reading a subversive racist subtext into everything will always remain. I believe Scalped to be the victim of what I call the stereotype that wasn’t there. By this, I mean that it is easy to assert that a creator is racist, but it is more difficult for said creator to conclusively prove that they’re not, meaning a piece of fiction can be burdened with a vague stigma of racism even without any substantial evidence to actually confirm what, with Scalped, too often amounts to overreaching assertions built on skewed interpretations.

Sadly, this mindset only hinders the representation of Natives (and other minorities) in fiction. It can be a vicious cycle, with writers reluctant to tackle minority-based stories for fear of being perceived as racist and so contributing to the underrepresentation of these minorities in fiction. And when a minority character does see the light of day, are they to be portrayed in a manner more “sensitive” (some would say patronizing) than their white counterparts, so as not to offend anyone? What a regressive view of minority characters, where their loftiest aspiration should be to not be offensive! Some critiques go so far as to suggest we should only allow white characters to be featured in crime stories, to be sure no one can equate any minority to criminality. I would say this is a dangerous precedent to be setting in the name of “equality”. It seems like backwards logic to me, that because there aren’t enough minority-focused stories out there, we should further limit them by branding certain genres out-of-bounds for anything but white characters. Isn’t it a better solution to stop viewing characters as “white criminals” or “Indian criminals”, to look past their color for more substantial ways of defining them?

With Scalped, Jason Aaron demonstrates that a Native American character can be just as flawed and damaged as a white character. Far from being racist, I would suggest that is a necessary step towards that sought-after equality.

One could argue that Scalped is too violent, too foul-mouthed, too unrelentingly bleak and depressing. These are all complaints based on what is right there on the page, ready to be received by its audience in one way or another. Accusing the book of racism, however, is dependent on leaps of logic and speculation on both the writer’s intention and the response of other readers that are insulting to both writer and reader alike. For those yet to read the book, my recommendation would be to check out Scalped for yourself – there are currently five graphic novel collections available – and make up your own mind about it. But please, judge it on its merits as a crime story or a character drama rather than on its stereotypes or lack thereof, because Scalped is so much more than just an “Indian comic”.