A couple of weeks ago, I wondered whether we could trace the entire sidekick-derived wing of DC’s superhero-comics history back to Bill Finger. Today I’m less interested in revisiting that question -- although I will say Robin the Boy Wonder also owes a good bit to Jerry Robinson and Bob Kane -- than using it as an example.

Specifically, this week’s question has nagged me for several years (going back to my TrekBBS days, even), and it is this: as between Alan Moore and the duo of Marv Wolfman and George Pérez, who has been a bigger influence on DC’s superhero books?

As the post title suggests, we might reframe this as “who won the ‘80s,” since all three men came to prominence at DC in that decade. Wolfman and Pérez’s New Teen Titans kicked off with a 16-page story in DC Comics Presents #26 (cover-dated October 1980), with the series’ first issue following the next month. Moore’s run on (Saga of the) Swamp Thing started with January 1984's issue #20, although the real meat of his work started with the seminal issue #21. Wolfman and Pérez’s Titans collaboration lasted a little over four years, through February 1985's Tales of the Teen Titans #50 and New Teen Titans vol. 2 #5. Moore wrote Swamp Thing through September 1987's #64, and along the way found time in 1986-87 for a little-remembered twelve-issue series called Watchmen. After their final Titans issues, Wolfman and Pérez also produced a 12-issue niche-appeal series of their own, 1984-85's Crisis On Infinite Earths.* The trio even had some common denominators: Len Wein edited both Titans and Watchmen (and Barbara Randall eventually succeeded him on both), and Gar Logan’s adopted dad Steve Dayton was friends with John Constantine.

If Titans and Crisis versus Swamp Thing and Watchmen were the whole tale of the tape, it’d probably be enough -- but of course it isn’t. Moore also wrote one of the definitive Superman stories, “For The Man Who Has Everything” (1985's Superman Annual #11), an even-more-definitive Joker story, 1988's The Killing Joke, and 1986's elegaic “Whatever Happened To The Man Of Tomorrow?” Later in 1986, Wolfman literally helped redefine Superman with twelve issues’ worth of The Adventures of Superman (plus a big role in the conception of post-Crisis Lex Luthor), while Pérez (with writers Greg Potter and Len Wein) relaunched Wonder Woman.

Of course, Crisis facilitated the changes to Superman and Wonder Woman (and, not incidentally, helped make “Whatever Happened...?” possible). It also allowed Wolfman and Pérez to depict Wally West’s graduation from sidekick to headliner, as he took over the role of the Flash from his late uncle. Not quite two years before, the duo showed Dick Grayson similarly giving up his Robin identity for the long pants and disco collar of Nightwing; and as the ‘80s drew to a close, Wolfman and Pérez (with artist Jim Aparo) would introduce the third Robin, Tim Drake, in the Batman/Titans crossover “A Lonely Place of Dying.”

Accordingly, we might see this question in terms of quantity versus quality. While Wolfman and Pérez left their rejuvenative fingerprints on a multitude of DC’s characters (not to mention the underlying cosmology), Moore infused the relatively-few characters he wrote with new sensibilities and fresh perspectives.

However, I’m not sure that’s entirely accurate. New Teen Titans was a superhero soap opera, compared virtually from the start to Uncanny X-Men, but it was an extremely well-done soap opera. Simmering subplots like Starfire’s confrontation with her diabolical sister, and the year-long buildups to “The Judas Contract” and Donna’s wedding, demonstrated the eventual emotional wallops that monthly comics could produce. Likewise, no discussion of Moore’s work is complete without mentioning the hidden depths he found in Swamp Thing and Watchmen’s Charlton-derived creations.**

Instead, in gross terms I believe the difference between Moore and Wolfman/Pérez is one of direction. Although Wolfman and Pérez did a lot to update, “modernize,” and otherwise develop their characters organically, basically their approach was conservative, in order that those characters could still function as familiar going concerns. Even Dick’s and Wally’s graduations, progressive as they were at the time, came out of more practical needs. The Bat-books and Titans each wanted Dick/Robin for different purposes, and separating Dick from his original alter ego made both sides happy. Conversely, Wolfman and Pérez never quite knew what to do with the ultra-powerful Kid Flash, so in Titans’ first three years they made him a reluctant hero (who’d actually retired upon his graduation from high school), revealed that his speed was killing him, and had him quit the team. Fortuitously, Crisis cured him, depowered him sufficiently, and gave him a new reason (honoring his uncle) to be a superhero.

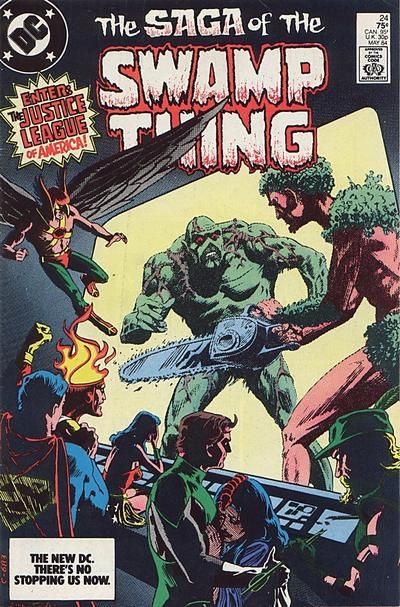

With Swamp Thing and Watchmen, though, Moore pretty much blew up familiar status quos in order to take his characters into uncharted territory. Even his depiction of the Justice League, in Swamp Thing #24, was nontraditional, among other things describing the JLA Satellite as “a house above the world where the over-people gather.” Moore had Swampy fight Batman and Luthor, but he also took the character into space and across dimensions. Obviously he had to have both character and book continue uninterrupted, but apart from that Swamp Thing’s narrative range expanded dramatically.

And then, of course, Watchmen blew up superhero comics themselves.

Now, at this point I suspect some of you may be wondering where a certain ex-Daredevil writer/artist fits into our DC-1980s retrospective. Somewhere between, I’d say; maybe closer to Moore than to Wolfman/Pérez, but maybe not as close as you’d think. Frank Miller’s Dark Knight and (with artist David Mazzucchelli, naturally) “Batman: Year One” set a new standard for Batman stories, just as Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams had done fifteen years before. I don’t include Miller with Moore or Wolfman/Pérez because he didn’t do a lot of Batman -- four 48-page issues of Dark Knight and four 23-page issues of Batman -- but pretty much instantly he became the main influence on the character for at least the next decade.

More generally, Dark Knight and Watchmen were a one-two punch in favor of ... well, hyper-violent, grim ‘n’ gritty superhero comics. Dark Knight especially showed how a well-known character like Batman could be revitalized through such an approach, and not long after Mike Grell was using the hyper-violent Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters as the pilot for a gritter, grimmer GA ongoing series.

Nevertheless, as prevalent as it was, grim ‘n’ gritty didn’t become ubiquitous across DC’s superhero line. Pérez’s Wonder Woman, Mike Baron and Butch Guice’s Flash, and the Keith Giffen/J.M. DeMatteis/Kevin Maguire Justice League International each had distinctly different tones, as did the biggest post-Crisis relaunch, John Byrne’s Superman.

I mention the Byrne Superman in this context largely because it was seen as evidence of DC’s “Marvelization.” In 1986 Byrne came to DC fresh from an extended, well-received run on Fantastic Four, just as Wolfman and Pérez had started New Teen Titans following their own well-regarded Marvel work. Titans might have been DC’s response to the success of X-Men; but it was also seen as a “Marvel-style” superhero soap, driven more by raw emotion than by fidelity to some square Silver Age ideal. Similarly, Marvel’s tighter continuity (and lack of reliance on an allegedly convoluted Multiverse) helped justify Crisis’ cosmic housecleaning.*** Add in Miller, doing for Batman what he’d done for Daredevil, and a pattern starts to form.

Even so, I believe Moore’s contributions to DC’s tonal palette have surpassed Wolfman and Pérez’s. The duo might have taken DC further down the road to Marvel-style storytelling, but the publisher had been on that road for a while already. After all, writers like Gerry Conway and Steve Englehart had similarly crossed over in the ‘70s. Moore’s success helped start a “British invasion” of writers and artists, leading eventually to the likes of Neil Gaiman on Sandman and Grant Morrison on Doom Patrol, Animal Man, and JLA.

In short, even though Wolfman and Pérez were wildly successful in their own right, Alan Moore’s influence led to the creation of a whole new line of comics. Moreover, the Vertigo style bled back into the superhero line, both in the ‘90s with JLA and James Robinson’s Starman scripts, and today in its own corner of the New 52.

This topic definitely deserves more space than I can give it today, but for now I’m content to give Moore the edge over Wolfman/Pérez. Tonight I will sleep just a bit more soundly ... that is, if I don’t start thinking about Len Wein....

++++++++++++

* [Moore also pitched a line-wide crossover, the dystopian-future Twilight of the Superheroes, but for various reasons it was never produced.]

** [Let me be clear: the phrase “Charlton-derived” is used solely for shorthand, and is in no way intended to diminish Moore’s role in creating the world of Watchmen. I’m not getting into that fight here.]

*** [In fact, a letter to the Wolfman-written Green Lantern, which confused Magneto with Dr. Polaris, helped get Wolfman thinking about streamlining DC’s continuity.]