First off, yes, I have read the first issue of Batman Eternal, but since its “pilot episode” includes issues #1-3, I’ll be talking about those more specifically in a couple of weeks. Eternal is one of two weekly series DC will offer this year, the other being Futures End, a look into the shared superhero universe five years from now.

However, we might well ask what difference will there be, one year from now, between an issue of either series and your average issue of a monthly title? When Eternal and Futures End are collected in their entirety two years from now, how different will they be from collections of Court of Owls or Throne of Atlantis?

The obvious differences are time and volume. The year-long weekly comics that DC put out from 2006 through 2009 -- 52, Countdown and Trinity -- all used their speedier schedule to tell a big story in a (relatively) short time. Instead of letting their epic tales play out over four-plus years, these series each got ‘em done in one.

Now think about sitting down with one of these thousand-page sagas. It won’t take a year to read, but it’s not something to approach lightly. That puts a special emphasis on how they’re to be read. Today we’ll look at DC’s history with weekly series (and some related experiments), with an eye toward what the two new ones might offer.

* * *

Weekly superhero comics tend to go against some well-established rhythms. Those of us in the every-Wednesday crowd no doubt expect to see new issues of our favorite series only once a month. That frequency affects our expectations about each issue’s content -- i.e., is it enough to tide us over for another four to five weeks? The time between issues also gives us an opportunity to digest and/or revisit the story so far.

Again, in contrast with the collected-edition reading experience -- where the bigger picture might emerge more clearly -- a weekly series’ rhythms may run the other way. Often, the weekly schedule gives creative teams the opportunity to explore characters and subplots in more detail. It’s basically a different format, even if the issues are the same length as those in a regular monthly series.

This was most apparent with 52 (2006-07) and Countdown (2007-08), which pretty much helped bridge the gap between Infinite Crisis (2005-06) and Final Crisis (2008-09). Similarly, in the wake of Blackest Night, DC published two concurrent year-long biweekly series, Brightest Day and Justice League: Generation Lost (both 2010-11). The Trinity series (2008-09) stood on its own, although it picked up on lingering subplots from writer Kurt Busiek’s short-lived JLA run. We’ll get into their specifics a little later.

To me, though, DC’s forays into a more-than-monthly schedule started in the early 1980s, when Gerry Conway was writing both Batman (which came out on the second week of every month) and Detective Comics (which got week four). For over five years, the two Bat-books shared the same plotlines, with only gradual turnover in the main creative teams. (Initially, Conway had Gene Colan and Don Newton trading off on pencils, and Dick Giordano editing both titles. By 1986, Doug Moench, Tom Mandrake and Len Wein had succeeded Conway, Newton and Giordano.) The arrangement allowed the creative teams to tell a variety of stories, from the soap opera of Jason Todd’s adoption to shorter, villain-specific arcs, and even a few standalone issues. After a while, Detective started running a Green Arrow/Black Canary backup feature, which shortened the main Bat-story and probably helped the biweekly logistics.

The Bat-books went back to separate tracks in the summer of 1986, coincidentally around the time John Byrne was relaunching Superman in the biweekly Man of Steel miniseries. I mention that not because of any logistical innovations, but because it may have gotten readers prepared for Byrne writing and pencilling two of the three upcoming Superman series. Byrne’s Superman and Action Comics didn’t flow into each other -- or, necessarily, into writer Marv Wolfman and penciller Jerry Ordway’s Adventures of Superman, which came out in the week between Byrne’s books -- but the three Super-titles all referred to each other, orienting readers frequently as to what was going on and where. When Wolfman left Adventures after a year, Byrne took over as writer, and made the connections more explicit. Consequently, when Byrne himself left in the summer of 1988, Superman and Adventures were pretty much interconnected.

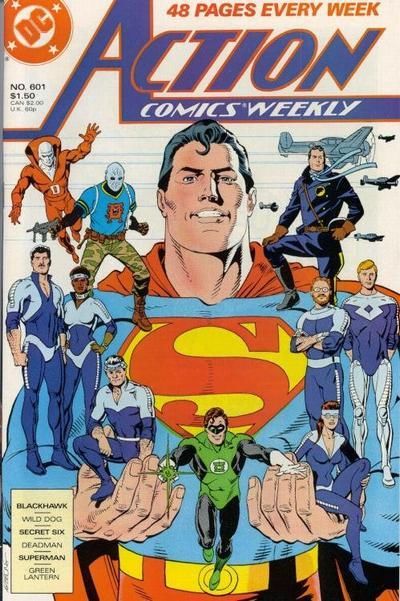

But wait -- what about Action Comics? Well, following Action #600, the title went on hiatus for a couple of months, returning as Action Comics Weekly #601. Besides being the new home of Green Lantern (the main GL book having been canceled), it featured five eight-page features and a two-page Superman serial. The latter wasn’t connected with the main Super-titles, and otherwise not much from ACW had an impact on the larger DC Universe. Exceptions included “Blackhawk,” which led into a short-lived ongoing series after ACW ended; “Black Canary,” showing the return to her classic jacket-and-fishnets look; and “Green Lantern,” which led off with Star Sapphire killing Katma Tui. By and large the ACW features -- among them “Nightwing,” “Shazam,” “Catwoman,” “Secret Six,” “Wild Dog,” “Phantom Stranger” and “Deadman” -- weren’t bad, but ACW didn’t go out of its way to seem essential.

After 42 weekly issues, Action reverted to a regular-sized monthly series -- and, more pertinently, returned to the interconnected Superman line -- in the summer of 1989. Although the Super-titles came out like clockwork, with Superman on the second week of each month, Adventures on the third, and Action on the fourth, DC eventually ratified the order with “triangle numbers” on their covers. From Superman vol. 2 #51 (cover-dated January 1991) to Action Comics #785 (January 2002), and later including the ongoing Superman: The Man Of Steel, the four-times-a-year Superman: The Man Of Tomorrow, and assorted specials, the triangles helped readers keep things straight.

More importantly (for our purposes), these “weekly” Superman titles were a model of production efficiency. Even before the line expanded to cover every week of the year, the various creative teams could collaborate on storylines of all sizes, knowing that readers wouldn’t have to wait as long between installments. They could show Clark and Lois’ relationship progressing at its own pace -- and in something approaching real time -- and build up to milestones like their engagement and his revealing the secret identity. They could also frame bigger arcs like “World Without A Superman” around the supporting characters, and gauge whether other characters like Supergirl or the Newsboy Legion could carry separate miniseries. However, that also meant giving up a good bit of control over the individual series, so after more than 10 years the triangle numbers disappeared and the Superman books each went their separate ways.

* * *

Still, superhero titles cross over all the time, especially when they’re related. With the biweekly Bat-books and the weekly Super-titles, the difference seemed to be one of dedication. We’re not talking about the occasional four-title Green Lantern crossover -- these were five- and ten-year stretches of constant interconnected storytelling. It was the same number of pages, but the concentrated focus created a more expansive environment.

We can see something similar in DC’s weekly events of the late 1990s. The Final Night (1996), Genesis (1997), DC One Million (1998) and Day of Judgment (1999) each came out in four or five weekly installments over the course of a month or so. However, each of those issues tied into most of the DC superhero books already scheduled for that week. Thus, while the main story of DC One Million involved four issues of the miniseries, an issue of JLA and assorted bits from various tie-ins, the whole thing covered dozens of issues and filled a thousand-page Omnibus hardcover.

Of more interest to us, though, may be the weekly Batman mega-arc called “No Man’s Land.” Starting with the prefatory “Cataclysm” arc in the fall of 1998, “NML” was serialized weekly in the four main Bat-books (Batman, Detective, Legends of the Dark Knight and Shadow of the Bat) for all of calendar year 1999. Likewise, it proceeded roughly in real time, telling a story that stretched from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31. It was broken up into various arcs, each told by a different creative team. This was almost the opposite of the Superman titles (or the Bat-books themselves, on occasion), which told stories across the different titles but kept the same creative team on each book. It made sure that particular stories were associated with particular creators, even as those stories built on each other to inform the larger mega-arc.

* * *

That brings us to 52. One of “NML’s” main writers was Greg Rucka, then new to the Bat-books but soon to become one of DC’s “Architects.” A big part of that ascendancy was his work on 52, wherein Rucka and co-writers Geoff Johns, Grant Morrison and Mark Waid each handled a particular set of storylines, and Keith Giffen did the breakdowns for various artists to pencil and ink. Designed to tell the story of an unusual year on DC-Earth, it took its real-time format very seriously, with each issue beginning on the week’s “Day One” and ending on “Day Seven.” The only deviation from the “one issue = one week” rule was the four-part World War III spinoff miniseries (not produced by the regular creative team), and all four of its issues came out the week that “World War III” occurred in the main series. Within that rigid structure, though, 52 turned out consistently-entertaining stories about lesser lights like Booster Gold, Animal Man and the Question; and introduced Batwoman, albeit in a very embryonic form. Accordingly, 52 is remembered fondly.

For a follow-up, DC produced Countdown, which had some obvious counterpoints to 52. While 52’s hooks were its lack of big names and its intended niche status -- filling in the continuity gaps between the end of Infinite Crisis and the regular books’ back-to-normal “One Year Later” storylines -- Countdown would be a year-long advertisement for 2008's Final Crisis. Moreover, it would be the “spine” of DC’s superhero books, tying into smaller events like Bart Allen’s death in Flash: Fastest Man Alive, the Amazons Attack miniseries, a familiar set of Legionnaires from the most recent JLA/JSA team-up and the newly-discovered Multiverse. Instead of a four-headed writing team working with Keith Giffen, Countdown was headed by “showrunner” Paul Dini, overseeing a collection of writers and artists (eventually including Giffen, coming back on breakdowns); and it turned out to be a huge mess. Essentially it was a hodgepodge of loosely-connected storylines -- and tie-in miniseries designed to capitalize on the Countdown “brand” -- the last of which were a) a rat-borne plague on Earth-51 that turned it into Kamandi’s Great Disaster, and b) a trip to Apokolips that ended with Mary Marvel becoming corrupted.

Countdown was all over DC’s superhero line for that year, but it was a failed product of the publisher’s opportunism. Although advertised as “important” to the superhero books, naturally it wasn’t “required” reading, because of course all the company’s titles stood on their own. Moreover, it was produced without much consultation with Final Crisis writer Grant Morrison, and so didn’t really tie into that miniseries as directly as one might have hoped.

After Countdown, DC took a break for a few months before launching Trinity, written by Kurt Busiek and pencilled by Mark Bagley. Trinity represented Bagley’s first DC work, and his reputation for timeliness seemed to suit the weekly schedule. Compared to its predecessors, Trinity combined their strengths: it was a standalone miniseries like 52, but like Countdown it focused on “the bigs,” namely Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman. While it didn’t unfold in real time, it did stick to a standard structure: a main story by Busiek and Bagley, and a related backup written by Fabian Nicieza and drawn by various artists including Scott McDaniel and Tom Derenick. I enjoyed it (and, for some bizarre reason, enjoyed writing about it every week), but it didn’t sell as well as 52 or Countdown.

Trinity was DC’s last year-long weekly miniseries for a while, but weekly comics weren’t gone entirely. Wednesday Comics was a 12-issue “newspaper-style” weekly miniseries that came out in the summer of 2009. Like Action Comics Weekly, it was an anthology mixing the big names with some lesser-knowns. Each issue contained one oversized page (physically, about the size of four regular comics pages) worth of story for each of the 15 features, and the creative teams could structure their stories however they wanted. Accordingly, while WC showcased a wide range of artistic styles, it also emphasized the immediacy of a weekly comic, with each feature having to hit its particular beats efficiently and effectively.

In 2010-2011, Brightest Day and Justice League: Generation Lost capitalized on various characters being revived at the end of the Blackest Night event. Each ran biweekly for a year, but in terms of both creative personnel and focus, BD was closer to 52 -- parallel story tracks produced by dedicated sets of creative teams -- while JL: GL was written by Judd Winick and drawn by a rotating set of artists including Aaron Lopresti, Joe Bennett and Fernando Dagnino. Brightest Day tied into several DC series, including Flash, Birds Of Prey and Green Lantern, but JL: GL stood largely alone. Indeed, it seemed likely that JL: GL would lead to a revival of Justice League International, but the eventual revival of JLI used a different, New 52-centric backstory.

Finally, DC’s digital-first comics deserve mention, inasmuch as they come (or came) out weekly. Like the Wednesday Comics features, they come out in smaller chapters before being assembled into regular-sized print comics, and from there into bound collections. Since I am so single-print-issue-oriented, the only digital-first comic I read is Batman ‘66, whose cliffhangers are pretty much an integral component of its unique style. Regardless, it’s not hard to pick out the chapter breaks in print versions of other digital-first offerings like Legends of the Dark Knight or Smallville Season 11.

* * *

We’ve seen that the rhythms and volume of a weekly (or biweekly) story can distinguish it from the more familiar 20-odd pages per month. However, the story’s “importance” also seems to be significant. 52 started out as an extended epilogue to Infinite Crisis, because the regular monthly series had already jumped ahead a year to establish their new status quos. It wasn’t immediately important, but it offered a glimpse into the mysteries of that lost year. Therefore, Countdown would be “52 done right” because it would tie directly into the current superhero comics. Likewise, it’s easy to see DC discounting Trinity and Wednesday Comics because they weren’t tied-in that directly. This might even have been foreshadowed in the ‘80s, when the Bat-books and Super-titles adopted interconnected storylines as an ongoing practice, but the less-essential Action Comics Weekly never really caught on.

Clearly DC wants to make sure readers know Batman Eternal and Futures End are capital-I Important. Scott Snyder is co-writing Eternal, and Futures End is getting a Free Comic Book Day preview. Both have the aura of grim inevitability, which comes from being part of the DC Universe’s not-too-distant future. (Indeed, “grim inevitability” might be one of DC’s slogans at this point, given the lingering effects of Forever Evil.) While all this buildup is obviously designed to get readers into the story right now, that’s something DC wants with all its comics. What’s different about these weekly series is the sense that if you don’t get in right now, you’ll be overwhelmed later. Arguably that supersedes the story’s “importance” because it puts the focus back on the story’s merits, but in a practical sense the two impulses work together: each issue is important for its immediacy.

It’s a pretty clear play to the participatory aspects of comics readership. Heck, it even plays out on a larger scale in other media. I’m willing to bet that far more people saw Captain America: The Winter Soldier over the weekend, and then watched Tuesday’s follow-up episode of Agents of SHIELD, than are waiting to watch ‘em in even quicker succession on home video. Batman Eternal #1 is certainly not a standalone issue, but neither is it as narratively dense as a regular monthly comic. Instead, by dividing its time between introducing an old character to the New 52, and showing Batman and Commissioner Gordon fighting Professor Pyg, the issue offers quick, apparently representative scenes intended to keep readers interested.

And that may well be the last big difference between a year-long weekly series and the average monthly ongoing: commitment for the long haul. It sounds counter-intuitive, but consider that these days, the regular monthly ongoings tell stories in discrete chunks. If you decide to stop buying Batman or Detective tomorrow, you can pick it back up without too much fuss when the collections come out; and you can catch up by reading however-many issues you missed. Bailing on a year-long weekly series, though, gets riskier the deeper you get into it. Odds are you’ll need to read more to catch up, the collections may be farther off (because they’ll collect more -- 52 and Countdown each took four collections, and Trinity took three), and if the series turns out to be either popular or “important,” those social pressures may be greater. At the risk of sounding like DC’s marketing department, it may be better to stick with the thing as it comes out -- but that still means having to decide, one way or another, fairly early on.

* * *

All this seems to indicate that DC has covered a lot of bases in setting up Batman Eternal and Futures End. The main problem with the latter may turn out to be its dependence on the conclusion of Forever Evil, which will now come out a few weeks after Futures End’s FCBD preview. However, both series seem to follow 52’s successful model of collaborative writers and compatible artistic styles. Both series seem to stand alone, as 52 did, but with enough ties to the current superhero books to make them important. Finally, the plots of both are based on pretty safe bets: a huge nightmare-vision of Gotham that only Batman and his allies can stop; and a huge nightmare-vision of the DC Universe that (ahem) only a future Batman and his allies....

Well, at least one’s got Stephanie Brown.

The bottom line seems to be that these big weekly series force an immediate choice on DC’s readership -- either get ready, or get left behind. Moreover, practical considerations associated with the weekly format tend to favor jumping aboard right away. The most intangible factor is also the most subjective; namely, how much each reader values that experience of immediacy, as well as the emotional and intellectual investments that accumulate over the year. Weekly comics can afford to play around with storytelling styles, but in the end they still have to give those first-line readers a reason to come back every seven days. We’ll find out soon enough how DC’s readership will vote.