Because this space is normally reserved for DC Comics and its stable of characters, you might think a post on Miracleman goes a little outside the lines. However, Miracleman was based on Captain Marvel, who is a DC character in the same way that Miracleman is now a Marvel character: the wonderful world of intellectual-property rights. That’s just one of several traits the two features share, so today I’ll be comparing and contrasting. I’ll also consider whether Marvel’s upcoming Miracleman revival could affect DC’s latest version.

Miracleman (under its original name of Marvelman, but you knew that already) started out as a way to hold onto British readers of Captain Marvel when the latter closed up shop in the mid-1950s. In that form, the series lasted until 1963. In 1982, writer Alan Moore headed up a revival that started by updating familiar elements, but ended up going off in a decidedly different direction. As reprinted, renamed, and subsequently completed in the United States, Moore’s Miracleman (from Eclipse Comics) filled 16 issues, give or take some reprints, and came out over the course of about four and a half years (cover-dated August 1985 to December 1989). Moore’s artistic collaborators included Garry Leach, Alan Davis, Chuck Austen (under the name Chuck Beckum), Rick Veitch, and John Totleben. From June 1990 to June 1993, Eclipse published eight more issues, written by Neil Gaiman and drawn by Mark Buckingham, and an anthology miniseries (Miracleman Apocrypha) came out from November 1991 to February 1992. For various reasons, though, no new Miracleman has seen the light of day for over twenty years.

That’s all about to change, starting with January’s reprints from Marvel. It remains to be seen whether today’s readers will be interested in 20- to 30-year-old stories from a writer whose popularity isn’t what it once was, and which will apparently be reprinted initially in a somewhat-pricey format. Additionally, Miracleman has turned into much more of an “Alan Moore book,” as opposed to a Captain Marvel parody. Therefore, its return doesn’t strike me as the sort of thing which will automatically generate more interest in Captain Marvel; but their similarities (and even some of their differences) can be instructive.

* * *

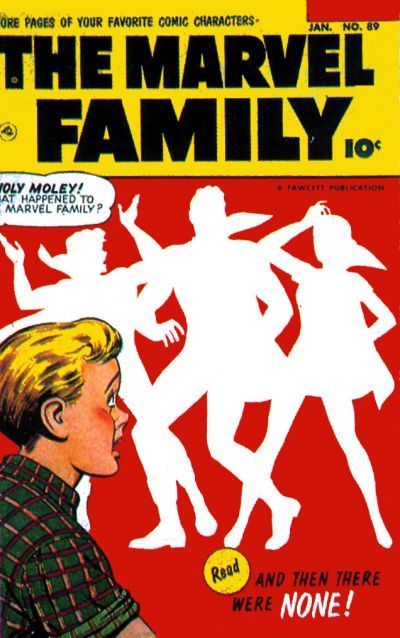

Captain Marvel was created by Otto Binder and C.C. Beck and first appeared in 1940's Whiz Comics #2, published by Fawcett Comics. One night, orphaned teenager Billy Batson followed a mysterious figure into a supernatural subway car which took him to the hidden dwelling of the wizard Shazam. Deeming him worthy, the wizard gave Billy the ability to turn into the super-powered adult Captain Marvel, whose abilities (derived from mythical figures Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles, and Mercury) included wisdom, super-strength, invulnerability, and flight. Later, Cap acquired two teenaged partners, both of whom basically stayed the same age when they transformed: Freddy Freeman, who became Captain Marvel Jr., and Mary Batson, who became Mary Marvel. The Marvel Family books quickly became popular, and before long the extended family included Uncle Marvel, the “Lieutenant Marvels,” and even Hoppy the Marvel Bunny.

For this longtime fan, there are many frustrations in the history of the original Captain Marvel. First is the legal challenge to the feature from National Comics, the company that would become DC. National/DC (hereinafter simply “DC”) thought Fawcett’s Captain Marvel was too similar to Superman, and thereby infringed on its intellectual-property rights. Both characters were super-strong and invulnerable, both wore capes and skintight costumes, and both could fly. As Pádraig Ó Méalóid points out -- and again, if you haven’t read the mind-bogglingly comprehensive “Poisoned Chalice,” you really should -- these days it would be a heck of a lot easier for Fawcett to fend off such a suit. However, in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, the comics marketplace was significantly different, and Fawcett ended up settling. One condition of the settlement forbade Fawcett from publishing future Marvel Family comics, so by 1954 Cap and his friends were off the shelves completely. In fact, the “Captain Marvel” name itself bounced around among various characters and publishers, until Marvel’s death-grip closed around it in the late 1960s. When DC acquired the rights to Fawcett’s characters,* and revived Cap and his friends in 1973, it called the new series Shazam! -- and so it has remained for lo, these many decades.

Nowadays, even the character formerly known as Captain Marvel is called “Shazam,” because DC figures that’s how the public knows him. One hopes that the public doesn’t confuse Cap/Shazam with that movie where Shaquille O’Neal played a genie, or with the app that tells you what the name of that song is. For that matter, one wonders how much money it would take for TimeWarner/DC simply to buy the trademark from Disney/Marvel (who could still feature its own Captain Marvel, albeit in a series called Warbird or Photon or Quasar) and avoid a lot of confusion. Neither of these are especially likely, but they are emblematic of the obstacles which keep DC from publishing straight-up traditional Captain Marvel stories.

Naturally, those original Captain Marvel (and affiliated Marvel Family) stories tended to be whimsical, light-hearted affairs. At least, that’s their reputation. Occasionally there were racist caricatures, the Captain Marvel Jr. stories drawn by Mac Raboy could get a little violent, and the conclusion of the “Monster Society Of Evil” saga ended with Mr. Mind -- who, villainous demeanor notwithstanding, was basically a cartoon worm only a few inches long -- being executed, stuffed, and put on display.

However, the idea of the Marvel Family as wholesome, innocent superheroes proved fairly resilient. DC’s revival even explained their 20-year absence by saying they (and all their friends, and some of their enemies) had been in suspended animation, literally unchanged since the mid-1950s. However, there weren’t a lot of Captain America-style “kids out of time” touches, and no “world’s gone to hell without the Marvels” motif. At first the new stories came from Denny O’Neil and Elliott S! Maggin, who had already become famous just a few years prior for their more “realistic” work on Batman, Superman, and Green Lantern/Green Arrow; but with Cap co-creator C.C. Beck returning as series artist (and late-period artist Kurt Schaffenberger helping out), things weren’t likely to get too grim.

Still, the “retro” approach only lasted about five years; and ever since, DC has struggled to find the right tone for Captain Marvel. The new direction started with Shazam! #34 (March-April 1978), whose cover featured an enraged Captain Marvel Junior about to kill his arch-nemesis, Captain Nazi.** The series was cancelled with the next issue, although the feature moved into the newly-expanded World’s Finest Comics. There it remained for about four years (26 bi-monthly issues), which in retrospect is a surprisingly quiet part of the character’s DC history. Heck, I didn’t know it ran that long; and it makes me want to seek out those old overstuffed WFs. Otherwise Cap appeared occasionally in team-ups with Superman (mostly in DC Comics Presents), and in a Golden Age setting in All-Star Squadron. From what I know, those stories tried to “modernize” the Marvels for the 1980s, while still keeping a fairly wide-eyed, optimistic attitude.

Finding the right light/dark balance hasn’t been easy. I only got one (depressing) issue into Roy Thomas and Tom Mandrake’s four-issue 1987 Shazam! The New Beginning miniseries, and didn’t even try the twelve-issue Judd Winick/Howard Porter Trials Of Shazam! relaunch from a few years back. It just looked like an overcomplicated route towards making Freddy Freeman the new Shazam, and I say that as someone who’s read his share of Donna Troy and Hawkman origin stories. Then there was Mary Marvel’s “bad girl” phase from the Countdown and Final Crisis period (2007-09), which pretty much speaks for itself.

Better-received were the Justice League International takes on Cap and Mary, which basically made them good-hearted, sympathetic saps; Alex Ross and Paul Dini’s coffee-table-sized graphic novel Shazam! Power of Hope; Jeff Smith’s kid-friendly Monster Society of Evil miniseries, which set up Mike Kunkel’s Johnny DC series; and of course Jerry Ordway’s reverent Power of Shazam! graphic novel and subsequent series, which probably worked the hardest and succeeded the most at finding that elusive balance. While Geoff Johns and Gary Frank’s current reboot (serialized in Justice League) seems more interested in making the characters seem “realistic,” they’re not exactly keeping the feature’s fantastic underpinnings under wraps.

* * *

By contrast, Moore’s Miracleman (which debuted in March 1982's Warrior #1) almost immediately went for gritty realism. Like the Marvel Family, Miracleman also spent a couple of decades in suspended animation, but his alter ego wasn’t stuck there with him. Michael Moran grew old, got married, and let himself go to pot, until a terrorist attack on a nuclear plant triggered the memory of his magic word. Moore used the dichotomy between human and superhuman to explore issues of identity. Before too long, Moran was firmly in the background, and Miracleman was thinking about how best to use his omnipotence. Other characters, like the easily-corrupted Kid Miracleman and the pragmatic Miraclewoman, offered their own perspectives on these matters. Meanwhile, Emil Gargunza, the evil scientist who had been our heroes’ main antagonist, was revealed as a more central figure in their adventures; and his role similarly allowed Moore to examine the role of fantasy in superhero stories ... sometimes in very unsettling ways. Moore’s run ended with (and Gaiman’s run then explored) a completely new status quo, not just for the series but for the Earth itself, as Miracleman and friends used what they’d found to integrate superheroics firmly into society.

There’s a lot more, but I am reluctant to spoil it for anyone. Besides the quasi-scientific gloss on switching into a super-body -- via another dimension, not unlike Rick Jones and Mar-Vell -- Moore came up with the requisite shadowy government agency (it was the early ‘80s, when such things were new), a group of extraterrestrial facilitators, and a way to incorporate all those nonsensical old stories into the modern continuity. Miracleman played out alongside Moore’s higher-profile 1980s works like Swamp Thing, Watchmen, and V For Vendetta, most of which used similar themes -- and/or pre-existing characters -- in more memorable ways. Specifically, Swamp Thing had more room to expand the main character’s mythology, and there was more focus on Doctor Manhattan changing the course of human history. Accordingly, Miracleman may be seen best as a sort of test bed for those kinds of ideas. It’s fascinating reading, particularly as a window on the “deconstruction” trend of the ‘80s, but I’m not sure it has either the scope or the structure to rise to the level of those successive works.

It’s not even a real commentary on Captain Marvel, at least not in the sense that Moore’s Supreme was a commentary on the Silver Age Superman. Miracleman merely uses the basic Marvel Family framework as a starting point. That probably means it’s not as “controlling” on the Marvel Family as, say, the alternate future of Kingdom Come -- or, for that matter, Moore’s Twilight of the Superheroes crossover pitch -- but as we’ve seen, the Marvel Family got dark enough on its own.

* * *

In fact, the character who’s probably benefited most from the various Marvel Family revamps has been the “fallen angel” of the group, Black Adam. As he did with Sinestro, Geoff Johns wrote Black Adam as the bitter, jaded realist who was knocked off his golden-boy perch early on, and who now scowls his way through life with little use for the goody-goodies who succeeded him. Black Adam was an adult when he got the power of Shazam, and he’s lived the hardest of lives -- starting off in ancient Egypt, which means a lot of living -- so he knows better than anyone how best to use his powers, and don’t you forget it. There’s no whimsy with Black Adam, and no inner child expressed in the joys of flight and super-strength; just a heart shriveled by disappointment and hardened by painful lessons. Kid Miracleman used his powers to make himself rich, and then went on a killing spree that pushed his old mentor almost to the limit. Black Adam would have settled KM’s hash by the end of one issue and set himself up as the punk’s long-lost father, back to claim his boy’s fortune.***

However, as long as Captain Marvel (or Shazam, or whatever DC ends up calling him) is around, Black Adam will always be the bad guy. Again, this isn’t necessarily bad news for the character, because he seems to be a more natural fit for today’s storytelling and tone. For that matter, the next time DC decides to relaunch the Marvel Family -- and there will be a next time, don’t worry -- they could probably do worse than to relaunch it around Black Adam. Make him the focus, make him as dark and brooding as he can be, but bring in Billy, Freddy, and Mary as the “new hopes” of the power of Shazam. Billy would be the David to Black Adam’s Saul, the Luke to his Anakin, the Harry to his Tom Riddle. You get the idea.

Normally this would be the point where I’d argue for the necessity of an unvarnished Marvel Family, all smiles and sunshine, in an otherwise murky DC landscape. I’d say the Marvels need to be on their own Earth again, where they wouldn’t have to take a backseat to Superman and Batman. (We may see this in action on that far-future day when Grant Morrison’s Multiversity comes out.) I’d plead for them to enjoy a more static environment, where they didn’t have to worry about aging into young adulthood alongside the other DC teenagers, and time could slow to a crawl while they enjoyed being kids.

I’ve just about given up on that, though. DC relaunched Shazam! 40 years ago, and discovered pretty quickly that even in the 1970s, Captain Marvel’s brand of storytelling wasn’t sustainable in DC’s superhero line. Alan Moore relegated the old Marvelman stories to mind-numbing computer simulations (or worse, in Miraclewoman’s case), and even the creators with the best of intentions treat Billy and company as somewhat anachronistic. There’s not going to be a traditional Captain Marvel feature at DC anytime soon, because there’s no incentive for DC to do one.

* * *

So what does more Miracleman mean for Shazam!? Probably not much. Even when Moore’s work was coming out initially, DC didn’t appear to change Cap in direct response. The two series were just so divergent narratively that Miracleman did its own thing, while DC kept trying to find a good take on the Marvel Family.

Ultimately, the similarities between the two features are more coincidental than anything else. Both ceased publication for upwards of twenty years, both put their main characters in in-story hibernation as a result, and both arguably work best apart from a shared superhero universe. (I’m not opposed to Cap and company visiting the main DC-Earth, but it would be pretty weird for Miracleman to pop over to Earth-616 to help the Avengers fight Kang.) However, because Miracleman developed from “what if Captain Marvel were real?” into “what if you could be a superhero,” it took on a much more philosophical tone. I suppose there’s now room in Miracleman for the kinds of lighthearted adventures the old Marvel Family enjoyed, but those would necessarily take place as part of a larger, and radically different, superheroic environment. Today Miracleman isn’t just the story of a grown-up Captain Marvel, or a Cap who grew up to be Shazam. It’s more like Cap growing up to be Doctor Manhattan, with a touch of Ozymandias. I don’t see DC taking Shazam! in a similar direction, unless it has an idea for After Watchmen ...

Regardless, “growing up” is the real complication. At its heart, “Captain Marvel” is a kid’s fantasy, which means that it must be ageless, because Billy and company can’t age. This won’t work in an environment of shared-universe superhero serials -- not even the Harry Potter comparison, because nobody wants to read about a middle-aged Harry Potter -- so more often than not it is relaunched, usually accompanied by protests from people like me. I said earlier that Miracleman wasn’t really a commentary on Captain Marvel, but that’s not entirely true. In a sense, Miracleman is the ultimate critique, because it claims that the fantasies we think we want are illusions, and the changes life has in store can be even more incredible than we might dream. Nothing remains static, and reality always wins -- but sometimes reality can be surprising. It’s a bittersweet viewpoint, one which seeks to be optimistic while at the same time reminding us that our dreams are just that. Nevertheless, it -- and Miracleman are meant for the grown-ups.

Meanwhile, I’ve been reading my 5-year-old selected stories from Showcase Presents Shazam! (she’s a big Mary Marvel fan). I’d like to think that as long as there are kids who love superheroes, there will be an audience for “Marvel Family Classic”-style stories. Of course, DC’s tried a number of different Marvel Family approaches, including the aforementioned Johnny DC series. Maybe someday DC will put it all together, but I don’t expect Miracleman to show them how.

++++++++++++++++

* [Footnotes? In a Miracleman post? Who’d have thought? Anyway, according to Wikipedia, DC started out licensing the rights to Fawcett’s characters from Charlton Comics, which had bought those rights after Fawcett stopped publishing in the ‘50s. DC didn’t buy the characters from Charlton outright until 1994.]

** [For those who came in late, Captain Nazi had killed Freddy’s grandfather and left Freddy for dead, and only Captain Marvel’s plea to Shazam saved Freddy’s life.]

*** [SPOILER ALERT -- Black Adam also gets a relatively heroic moment in this week’s Justice League #24.]