So much time, money and creative effort is spent to bring comic-book superheroes to moving-picture life that it’s almost backward to contemplate how those adapted environments could be translated back into comics form. Thanks to technology, live-action and animated adaptations are finding new ways to convince viewers they’re seeing powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men.

And yet, these adaptations only go so far. Movies trade spectacle for (relative) brevity, offering two-plus hours of adventure every two to three years. The reverse is true for television, which is more prolific but often less earth-shattering. Both have to deal with practical considerations such as running time, actor availability, and the streamlining of complicated backstories. Thus, to borrow a phrase from politics, adaptations are often exercises in “the art of the possible.” By comparison, comics have much fewer limitations.

Therefore, comics versions of those adaptations must necessarily limit themselves, even if they only choose to work within some of those real-world limitations. Sometimes this is as simple as telling stories set within the adaptation’s version of continuity. However, sometimes comics are the most practical way to “continue” a well-liked adaptation, and thereby perpetuate its visual and tonal appeal.

DC’s digital-first line includes adaptations of three TV series, which themselves were inspired by DC superheroes: Batman ‘66, Smallville Season 11 and Batman Beyond Universe. A series based on Arrow ended earlier this year, but with the show apparently doing well enough to spin off a Flash series, there’s no reason it couldn’t come back.

Still, DC has a pretty prolific library of adaptations. At DC Women Kicking Ass, the indispensable Sue has occasionally suggested that DC do a digital-first series based on the Lynda Carter Wonder Woman series (Wonder Woman ‘75, I suppose); and I agree wholeheartedly. While it’s common for fans of the comics to speculate about how their favorites could be adapted, for me it’s always been fun to imagine where those adaptations could end up. Therefore, today we’ll look at some other DC adaptations which could get the digital-first treatment, as well as DC’s history of turning its existing adaptations back into comics.

* * *

First, a disclaimer: I know right off the bat that I am not going to remember every DC-inspired movie or TV series. That's because I haven't seen every DC-inspired movie and TV series. Yes, this includes more recent series like Green Lantern, Young Justice, Beware The Batman and the DC Nation shorts. You may love ‘em, they are probably fine shows, and I wish I had the time to enjoy them all. (Specifically, I am leaving discussions about the Swamp Thing live-action and animated series to the world’s foremost muck-monster scholar.)

On a related note, I am not going to pretend that every DC-inspired adaptation deserves its own digital-first series. If you feel strongly about a new comics series for Josh Brolin’s Jonah Hex or Shaquille O’Neal’s Steel, or that JLA movie with David Ogden Stiers as Martian Manhunter, more power to you. However, there are always possibilities (to quote a character adapted into comics form by DC and others), so maybe Halle Berry’s Catwoman might show up in one of the hypothetical series discussed below.

Accordingly, let’s get on with it, shall we?

* * *

Strictly speaking, DC’s characters started being adapted into other media fairly early on. Most fans know about the Superman radio and movie serials (also featuring Batman and Robin), the Batman movie serials, and the Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman newspaper strips; but Captain Marvel, Congo Bill and Blackhawk each got movie serials as well (with the latter starring Kirk Alyn, the first live-action Superman). However, I think it’s safe to say that none of those is either sufficiently distinct from the source material, or sufficiently popular on its own, to revisit today. Those are the main criteria I’ll use in discussing various page-to-screen-to-page series, because together they tend to justify an adaptation’s comics counterpart.

Indeed, collectively the various screen Supermen illustrate the interaction of those criteria. The Superman comics have always had a close relationship with their adaptations, acknowledging their contributions in various degrees. Still, even though the comics brought Jimmy Olsen over from the radio serial, imported the crystalline Fortress of Solitude from the Christopher Reeve movies, and based various costume permutations on the Fleischer cartoons and the black-and-white George Reeves outfit, I contend that to date -- and pending whatever spins out of the Man of Steel movie -- only Smallville has created a sufficiently distinct vision of the Superman mythology.

To put it another way, consider what a comics series based on the Adventures of Superman TV series, the Reeve movies, or Lois & Clark, would look like. Because each would seek to expand its particular setup into more traditional Superman fare, I suspect none would be significantly different from a comparable Superman comic of the ‘50s, ‘80s, or ‘90s. In fact, many of the changes made by the first Reeve movie were incorporated into the comics’ 1986 reboot; and L&C was influenced heavily by the comics of the time (although it did encourage the comics’ Lois and Clark to hurry up and get married). For that matter, the Reeve movies were revisited on the big screen in 2006's Superman Returns, for which DC produced a set of comic-book prequels.

Now, I’m not saying that the occasional mash-up wouldn’t be worthwhile. I wouldn’t mind seeing Vartox in a Lois & Clark story, or George Reeves outwitting Mr. Mxyzptlk or Bizarro. I just don’t know how different it would be from those Gary Frank issues where he drew Clark/Superman as Christopher Reeve.

Accordingly, Smallville stands apart because by design, the series didn’t deal directly with “Superman” until its final episode. As such, it practically demanded a comic-book sequel, expanding on its array of familiar-but-different DC folk, and going further into characters it couldn’t touch, like Batman and Wonder Woman. While the artists on Smallville Season 11 have gotten away from drawing Tom Welling as Clark/Superman, that’s a minor complaint. The point of the comics series (written by one of its TV producers, Bryan Q. Miller) is to show the world of Smallville’s Superman, and in that respect it’s been very entertaining.

Similarly, while the Adam West Batman series wasn’t overly concerned with world-building, it certainly established a unique tone and sensibility that the Jeff Parker-written Batman ‘66 has captured impressively. The artists of Batman ‘66 (including Jonathan Case, Ty Templeton, Joe Quinones, Ruben Pincopio and Christopher Jones) extend this fidelity to the series’ look, even going so far as to “cast” both Julie Newmar and Eartha Kitt as Catwoman, where appropriate. (Colleen Coover drew Eartha Kitt as Catwoman in a Batgirl-centric story, because both Kitt and Batgirl debuted in the series’ third season.) My only complaint with Batman ‘66 -- and it’s even more minor than the Smallville one -- is that Parker and company introduced a version of Harley Quinn, a character who wouldn’t appear in any medium until 23 years after the Batman series was canceled. That’s going a little too far outside the series’ scope for me; but I’m probably in the extreme minority.

* * *

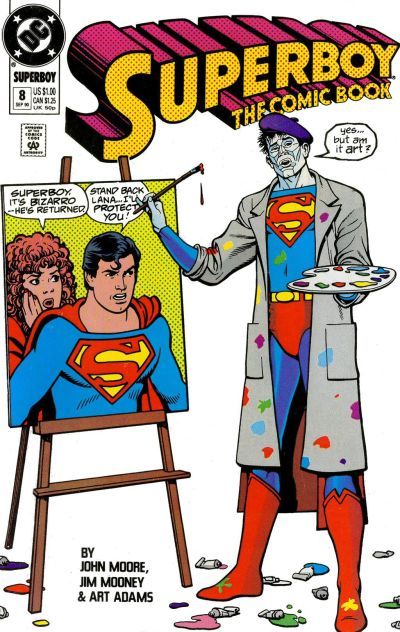

Before getting into the prospective series, I want to look back at those earlier comics adaptations of shows adapted from DC comics. Probably the most prolific are the DC Animated Universe comics, which started off with a six-issue Batman: The Animated Series miniseries. That led to a regular series (The Batman Adventures), which was relaunched occasionally to keep up with changes to the TV series’ title and format. Later came Superman Adventures, Adventures in the DC Universe (set in the DCAU, but not tied into a particular series), Justice League Adventures, and various Batman Beyond series and miniseries. In the early ‘90s, the live-action Superboy show got its own comic, which over 22 issues featured writer John Moore, pencilers Jim Mooney (one of the definitive Silver Age Supergirl artists) and Curt Swan, and inker Ty Templeton. Likewise, the live-action Flash series (1990-91) got its own comic-book special, and early in its run Smallville got a couple of specials and 11 issues’ worth of a series. Finally, non-DCAU animated series like Batman: The Brave and the Bold and the aforementioned Green Lantern, Young Justice, and Beware The Batman, have each been made into comics.

Today, of course, Batman Beyond Universe explores the DCAU future with stories focused specifically on its Batman, Superman and Justice League. Again, it’s a distinct “world” (even more so, since the New 52 relaunch) that remains popular long after the shows ended. As it happens, though, a couple of ‘70s DC TV series were integrated into regular comics continuity in somewhat surprising ways. The live-action Shazam! show featured Billy Batson tooling around America in a white RV with his older pal Mentor and a little device that connected him to the deities and demigods who gave him his powers. Consequently, the Shazam! comic did a handful of stories where Billy -- at the direction of his employer, TV station WHIZ -- took a white RV around America, accompanied by his old Uncle Dudley (who compared himself to a “mentor”) and a little deities-and-demigods device. Meanwhile, the Super Friends comic was set explicitly on the main DC-Earth (Earth-One), and did its best to reflect main-line comics continuity. The show’s two sets of “junior Super Friends” -- Wendy, Marvin, and Wonderdog; and Zan, Jayna and Gleek -- each got origins that tied them into the comics, and the Super Friends comic even did a story which showed the transition from one set of teens to the next. The Super Friends comic is probably remembered best for introducing the Global Guardians, who were later incorporated more fully into the regular comics (with Green Flame and Ice Maiden eventually joining Justice League International and becoming Fire and Ice).

* * *

Now that we’ve laid out adaptations that don’t really need their own comics and adaptations that have gotten their own comics, it’s time to look at adaptations which could justify their own comics. In the spirit of Batman ‘66, I’ll be using the year of the adaptation’s debut in the prospective comic’s title.

Naturally, first up is Wonder Woman ‘75, based on the Lynda Carter series. While the series’ appeal might rest largely with Ms. Carter’s winning portrayal, its differences could make for some intriguing storylines. The first season was set in World War II (1942-45), and took from the comics Queen Hippolyta, Steve Trevor, Etta Candy, and (for one episode each) villains Paula Von Gunther and Fausta. Diana’s sister Drusilla (played by Debra Winger) also appeared a couple of times as “Wonder Girl,” but she wasn’t costumed like Donna Troy and didn’t make it into subsequent seasons. After the first season, the show jumped forward into the mid-‘70s, and while Diana’s immortality allowed her to look the same, Lyle Waggoner had to play identical son Steve Trevor Jr. Both he and Diana Prince worked for a secret government spy agency, where for whatever reason they didn’t fight any of Wonder Woman’s traditional villains. Clearly a digital-first series might address ‘70s versions of the Cheetah, Giganta, and Doctor Psycho -- who’d fit especially well into the Me Decade -- but it could also play with the decades Diana spent away from the United States, after 1945 but before 1977. Maybe she had adventures in other dimensions; or maybe she explored the rest of the world (say, with a blind mentor who taught her martial arts and the finer points of wearing white). Wonder Woman ‘75 wouldn’t have to be all Nazis and/or cheap sets, is what I’m saying.

I mentioned the 1990-91 Flash series earlier, and while it may become something of a curiosity once the new series and/or a Justice League movie reworks the character, its single season created a distinctive environment. At a time when Bill Messner-Loebs and Greg LaRocque were building up Wally West’s supporting cast, producers Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo and story editors/comics pros Howard Chaykin and John F. Moore (who was writing that Superboy comic around the same time) were trying to make John Wesley Shipp’s Barry Allen appealing to viewers. They mostly ignored Iris West in favor of a platonic relationship with STAR Labs’ Tina McGee, and introduced a couple of new characters: Barry’s hipster police-scientist partner Julio, and Megan Lockhart, a feisty private-eye love interest. Although the TV Flash didn’t try to reproduce Barry’s Silver or Bronze Age adventures, it did use non-costumed versions of the Mirror Master and Captain Cold, and made the Trickster (played by Mark Hamill) more deadly and unbalanced -- albeit with a Harley Quinn-esque sidekick named Prank. The Flash was still inspired by a masked hero, only this time it was the Nightshade, who looked something like the Golden Age Sandman. While those last touches might seem reminiscent of Batman: The Animated Series, the Flash series predated it by about two years.

In any event, a Flash ‘90 series would have plenty of room to play around with familiar elements from the Flash comics, including the rest of the Rogues’ Gallery, Grodd, and Abra Kadabra. (One episode used a blue-clad Flash clone, so our hypothetical series might have to distinguish him from Professor Zoom.) Iris and/or Patty Spivot could complicate Barry’s relationship with Megan, Barry could team up with Kid Flash or the Elongated Man, and the Cosmic Treadmill and the Multiverse would be available too. It might not be as different as Wonder Woman ‘75, but it could be fun.

Similar in setup was the 2002 Birds of Prey TV show, which -- kind of like the upcoming Gotham -- was a Batman series without Batman. TV’s Birds were Oracle, Huntress and Dinah Lance, but only Oracle resembled her comic-book counterpart. Huntress was Helena Kyle, superpowered daughter of Batman and Catwoman, and Dinah was the telepathic daughter of an otherwise-traditional Black Canary. They lived in a post-Batman Gotham City and were friends with Alfred Pennyworth and (the secretly evil) Dr. Harleen Quinzel, but beyond that it was a lot of monster-of-the-week-style plots. As the series took the “Batman was an urban legend” trope very seriously, there was also a detective who refused to believe that anything paranormal was behind all the weird cases he investigated. Essentially, a BOP ‘02 comics series would probably get a lot more heavy into the Gotham side of things, since it could actually show Batman, Nightwing, Robin, et al., and maybe explain some of the series’ confusing-but-important backstory.

That brings us to an adaptation which naturally suggests a comics-based sequel, the Christopher Nolan Dark Knight trilogy. (SPOILERS for The Dark Knight Rises, of course.) The movies drew pretty heavily on the comics for inspiration, but then used those elements to take Batman into some unfamiliar territory. For one thing, they didn’t really give Bruce Wayne much of a Batman career. In Batman Begins he fights the Scarecrow and Ra’s al Ghul (and the Falcone mob, but that’s almost incidental). The Joker comes to light at the end of Begins, but several months go by before Batman captures him at the end of The Dark Knight. Harvey Dent’s death at the end of that movie then sets up Batman’s eight-year absence, which ends in Rises with the emergence of Bane. By the end of Rises, the League of Shadows is in ruins, but Batman is gone and Wayne Enterprises is bankrupt. However, there’s a new Bat-Signal on the roof of Police Headquarters, and someone new in the Batcave.

A fan-film postulates that this will be Nightwing, which is as good a start as any; but it is a Bat-Signal, after all, and there’s no reason to reinvent the Batsuit when all that gear is just sitting there. Besides, in the Nolanverse, the Joker and the Scarecrow are still alive (and one could easily bring back Ra’s), and Lucius Fox and Commissioner Gordon haven’t gone anywhere either. Batman ‘05 could tell Bruce Wayne stories set between Begins and Dark Knight, or post-Rises stories featuring the new guy and some new (or old) villains. If Nolan himself won’t go back to that setting, DC may well want to at some point.

Finally, though, there are the movies which -- for better and worse -- set both high and low standards for live-action superheroics. A Batman ‘89 comics series isn’t exactly a new idea, since the short-lived Batman newspaper strip was set loosely in “movie continuity” -- it started with the Joker’s apparent death, although it dropped him into the harbor instead of onto the concrete -- and Batman: The Animated Series was supposed to capitalize on the success of Batman Returns, in part by basing Catwoman and Penguin on their movie looks. However, I’d be eager to see a comics sequel based around Michael Keaton’s unique take on Bruce Wayne. Burton’s movies have their flaws (and we’ll get to Schumacher’s, don’t worry), but whenever they gave Keaton something meaningful to do -- particularly in Returns -- he brought intelligence, a distinct energy, and wit to the role. It was a performance as different in its way as Adam West’s was, and I contend it also deserves to be revisited.

To be sure, Keaton’s Batman inhabits a radically-different Gotham. When he found the man who killed his parents, his revenge took the form of heavy artillery, machine-gun fire, and eventually a plunge from an extreme height. He has two ex-girlfriends (Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle) who know his secret, and was ready to settle down with Selina. The Joker and the Penguin are dead, Harvey Dent disappeared between the first and second movies, there’s no Robin, and no evidence of a friendship with Commissioner Gordon. A Batman ‘89 series might begin by addressing any or all of these things, to see if they could be brought more in line with the classic Batman setup. Indeed, since the Halle Berry Catwoman apparently had some oblique connection with Michelle Pfeiffer’s, the two could conceivably meet -- although I wouldn’t lead off Batman ‘89 with that.

Naturally, if one were so inclined, one might also try to harmonize the Burton movies with the Schumacher movies, or (more simply) to craft a digital-first series based only on Batman Forever and Batman and Robin. Since those movies referred to the Burton films in the same way that Roger Moore’s Bond movies referred to Sean Connery’s, this Batman ‘95 series could add Robin, Batgirl (Alfred’s niece), Dr. Chase Meridian (yet another girlfriend who discovered the secret), and current flame Julie Madison. It could reuse Catwoman (either one, remember), Mr. Freeze and Poison Ivy, but its Two-Face would be dead and its Riddler would be a gibbering idiot (who also discovered the secret). There would also be a good bit of rubber nipples and neon, which almost goes without saying.

* * *

In the end, though, any such re-adaptation must work pretty hard to justify its existence. Batman ‘66 is based on a TV show which left its mark so indelibly on Batman and Robin -- not to mention superheroes and comics generally -- that it would barely be challenged, let alone superseded, in the public mind for at least twenty years. Today fans embrace it, but for years a significant group rejected it, decrying its mockery not just of their beloved characters, but of the genre to which they belonged. Although Tim Burton’s Bat-movies were part of Batman’s post-Adam West “rehabilitation,” I’m not sure their interpretation is as distinct, or as valid, as the show which inspired Batman ‘66.

Again, revisiting one of these other-media adaptations means working within some, if not all of the limitations that comics can normally choose to ignore. An adaptation has to be pretty special to warrant those kinds of concessions. However, this sort of exercise also implies that comics’ greater freedom could “fix” these adaptations, and thereby allow fans to enjoy them to the fullest. Now that is a powerful incentive to revisit a movie or TV show which could have been so good, if only....

It’s not exactly rewriting history -- more like overwriting it, using a more lax set of rules -- and I’ve looked at it from a somewhat conservative, reversion-to-the-mean perspective. Truthfully, while Wonder Woman ‘75 could explore the “white-suit” period, or Flash ‘90 could make Barry’s brother Jay the Flash of Earth-2, this sort of sanctioned fanfic could just as easily go off in any number of directions. That’s what Nolan and company did with their three Batman movies, and to a certain extent that’s what Burton did with Batman Returns. DC’s current digital-first adaptations succeed because they are evocative both of their moving-picture and four-color inspirations. That’s hard to do, and I’d hope DC aspires to that standard when evaluating similar prospects.

But I would still love to see Wonder Woman ‘75 ...