“I shall become a bat.”

One popular theory holds not only that “The Batman” was born at the moment Bruce Wayne was orphaned, but that the personality of eight-year-old Bruce was replaced with one dedicated to the cause of justice. Thus, the embryonic “Batman” traveled the Earth for the better part of seventeen years, learning the skills he would need for the cause to which he had become wedded. “Batman” shunned anything which would not advance that cause, because “Batman” was the only thing that made sense after all sense had left eight-year-old Bruce’s life. More particularly, only “Batman” -- and not Bruce Wayne -- was psychologically equipped for such a crusade, because (however paradoxical it may seem) only Bruce Wayne could become Batman.

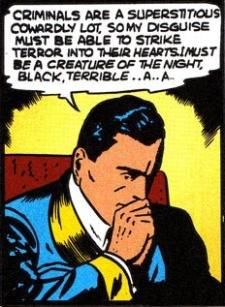

While that theory is very appealing, I don’t think it is supported completely by the generally-accepted accounts of how Batman came to be. After over seventy years, the origin’s main elements have not changed. The Waynes’ murders drive Bruce to a strict regimen of physical and mental training, but it’s still not enough. The first account, from November 1939's Detective Comics #33, famously finds Bruce in his library, puffing on a pipe and musing

Criminals are a superstitious[,] cowardly lot. So my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts. I must be a creature of the night, black, terrible, a ... a ... [cue the open window] A bat! That’s it! It’s an omen. I shall become a bat!

All but the last phrase was cut out of the “Year One” origin. As related in February 1987's Batman #404, a badly-wounded Bruce, disguised only as a disgruntled veteran, has just escaped police custody and must decide whether to bleed to death in shame or summon Alfred. This time the bat crashes through his window and perches, like Poe’s persistent raven, on a bust before him. Most recently, The Return Of Bruce Wayne #6 cast the bat not only as the thing which frightened young Bruce prior to his parents’ deaths, but as an avatar for darkness and even evil itself.

Heady stuff, to be sure, and while it looks fairly totemic, it speaks to a mature Bruce in constant conscious control of his own destiny, not a man possessed by some spirit of vengeance created out of childhood trauma. This is a Bruce Wayne who can pass on what he has learned, especially including how to keep “Batman” from dominating anyone else’s life. Personally, I find it hard to believe that “Batman” raised Dick Grayson, adopted Jason Todd, trained Barbara Gordon and Tim Drake, romanced Julie Madison, Linda Page, Selina Kyle, Vicki Vale, Silver St. Cloud, et al., befriended Jim Gordon, J’Onn J’Onzz, Ralph Dibny, etc., etc. This is a Bruce/Batman who would see the Bat-Signal and all the various Bat-gadgets cumulatively as a marketing strategy, as ubiquitous in Gotham as McDonald’s or Coke. One makes you thirsty, one makes you hungry, and one makes you think twice about sticking up that nice old Dr. Thompkins.

Why, then, does the post title assert that “no one knows what it’s like?” Aside from me wanting to paraphrase that Who lyric for who-knows-how long, I do still think there is something at Bruce Wayne’s core struggling for complete control. I don’t believe that “Batman” is Bruce’s dominant personality, because there is too much evidence to the contrary. Instead, “Batman” is a just-so-crazy-it-might-work response to the crime-dominated world of Gotham City -- and because only Bruce had the specific experiences which led to “Batman,” only Bruce understands “what it’s like.”

Again, though, that doesn’t mean Bruce can’t farm out “Batman” to Dick, or Sir Cyril, or Mr. Unknown, just like McDonald's lets local businesses use the Golden Arches. A good idea is a good idea, whether it’s a way to deliver food fast or a universal symbol for scaring bad guys. Besides, going global allows Bruce some measure of control, however indirect, over his franchisees. Remember, he never really approved of the Huntress until she agreed to wear that Batgirl suit back in "No Man's Land." Similarly, the events of Batman: The Return seem to confirm Bruce's decision to keep Damian as Dick's Robin -- and, naturally, there's still the new Batwoman, who has no real connection to any of the nominal Bat-Family.

Speaking of Batwoman, such "corporate control" clearly applies also to publishing concerns, but I am optimistic enough to think that DC will leave J.H. Williams III, W. Haden Blackman, and Amy Reeder alone for as long as they remain on her eponymous title. Ironically, it seems popular enough on its own (that is, with Williams' involvement) that it doesn't seem to need the boost of a "Batman Incorporated" brand. Bringing titles like Batgirl and Red Robin into the "Incorporated" fold may also be a touch unnecessary, since they too seem to have found their own audiences. "Incorporated" therefore looks more like Grant Morrison's and/or DC's attempt at unifying all the Bat-titles while still letting each of them have a particular direction. Dick gets the two foundational Bat-books, Batman and Detective, and stays in Batman and Robin and Streets of Gotham with Damian. (Dick also stays in Justice League.) Bruce headlines Batman Incorporated and the new Dark Knight, but is free to pop up anywhere else as required.

All this is fine for logistics, but what about style? What objectively separates Bruce's Batman from Dick's, or any future caped crusader's? For the better part of twenty years, influenced mostly by Frank Miller's work on the original Dark Knight and on "Year One," Batman was an antisocial figure, distrustful to a fault, respected and even loved almost despite his personality. The events of Infinite Crisis and 52, which helped set up Grant Morrison's current run, were supposed to make Batman "less dickish." I personally used to pitch Nightwing just that way -- as the "well-adjusted" Batman. (Less of a dick, more of a Dick, as it were.) Today, Bruce must necessarily cultivate better people skills in order to facilitate recruiting; so one might see this as dulling that longstanding, misanthropic edge.

Regardless, even without that concentrated mix of paranoia and condescension, Bruce won't get lost in the crowd. In Batman: The Return and in the first issue of Batman Incorporated, Bruce has become calmly confident without beating his associates over their heads with his confidence. One might even say he's enthusiastic about his new venture -- but it's a different kind of enthusiasm than that displayed by Dick Grayson. Dick's exuberance is rooted in a lifelong love of performing, while Bruce's may well come from the realization he's once again in control of his own destiny. "Batman Incorporated" could produce any number of actors, but for Bruce Wayne, Batman is literally the role of his life. I look forward to seeing how that role both evolves and remains unique.