What does Ed Brubaker leaving Captain America have to do with New-52 storytelling? For me, the connection goes through Gotham Central.

Okay, that requires a bit more explanation. Mr. Brubaker isn’t leaving Captain America on bad terms, but apart from Winter Soldier he’s not especially interested in writing any more superhero comics. It’s not the same as Chris Roberson’s principled departure from DC, but it puts me in a similar mood.

Like Roberson, Brubaker is a good storyteller who can incorporate shared-universe lore effectively into his comics. For example, Winter Soldier’s first issue started out as a straightforward super-spy caper, but abruptly veered close to Silver-Age-Wacky territory with [SPOILER ALERT, I guess] the arrival of a gun-toting ape. The rest of the arc combined a couple of longtime Fantastic Four villains (one minor, one pretty major) with the threat of regional warfare. It never did get truly goofy, but it was rooted in a Marvel Universe where the former Soviet Union had some pretty odd operatives. Of course, the Winter Soldier concept itself is a retcon (Bucky was revived as Soviet covert agent) of a retcon (he died near the end of World War II).

While Gotham Central didn’t trade extensively on DC trivia, its premise depended similarly on Batman and his allies being well-established elements of the law-enforcement landscape -- and being as odd to cops on the job as gorillas with assault weapons. That’s something I don’t think works as well in the New-52's five-year timeline, which isn’t quite comfortable with its treatment of superheroes to take the air out of them. Put another way, it’s a concept which works best when you’re kind of tired of the very idea of Batman, so it helps if Batman’s been around for a while (i.e., so he’s had enough time to become annoying). Otherwise, it risks sounding contrived: “WHY-IS-THIS BAT-MAN-HUMP BUSTING-MY-BALLS?” It’s like launching Justice League Dark and JLI at the same time as Justice League -- you don’t have time to get used to the primary book, so you have less context for the spinoffs.

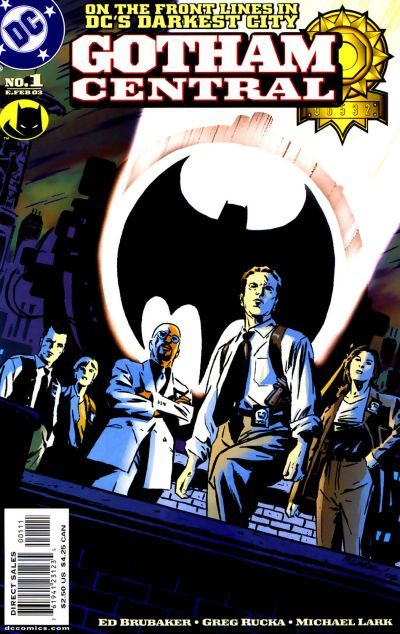

First, though, some background. Before moving to Marvel, Brubaker had well-regarded runs of varying lengths on a handful of Batman titles. (Speaking of shared-universe lore, one of his supporting characters was the daughter of venerable Gotham gangster Lew Moxon.) He co-created and co-wrote Gotham Central with Greg Rucka in 2003, and wrote all or part of 22 of the first 36 issues. In fact, part of Gotham Central’s inspiration later became one of Brubaker’s Batman stories:

“[T]he first Batman story I ever pitched ... ended up being cannibalized later to become Batman #603,” [Brubaker told CBR in 2003]. “At the time the story was called ‘Slam Bradley’s Final Case’ and Michael Lark and I pitched it as a one-shot [for] Legends of the Dark Knight, and it got shot down. It’s a story about the investigating officer in the death of Bruce Wayne’s parents, and it was about how Batman and his villains changed the way the job is in Gotham.

“Greg liked that idea, and he’d been trying to put more and more cops into Detective at the time, and so we just sort of kept talking about doing a cop book in Gotham.”

In 2011, Brubaker explained further to The A.V. Club:

[W]e realized how cool it would be if we did a comic like this every month. Where it was always about a crime scene where The Joker walked through and killed a bunch of babies. Just seeing the horror from a perspective that… You don’t see it from Batman’s point of view. These people, they do this every day to the point that it becomes a grind. And how angry they must get, and feel powerless that they can’t catch these people, but Batman’s going to do it. And half of the time, they’re not gonna get convicted, because Batman arrested them. Things like that. It just seems like a comic that really needed to exist.

Indeed, for most of the 1990s the Bat-books flew pretty high above street level, balancing brutal, high-stakes action with gaudy superheroics. Often this meant inter-title crossovers, starting with 1993-94's “Knightfall,” “KnightQuest” and “KnightsEnd,” wherein a new Batman made himself into a shiny, pointy action figure to demonstrate just how deadly serious he was about the grim business of eradicating crime. After the old Batman returned, the events continued: fighting Russian mobsters in “Troika,” trying to stop a deadly super-virus in “Contagion,” chasing Ra’s al Ghul around the world in “Legacy,” and then dealing with a massive Gotham earthquake in “Cataclysm,” “Aftershock,” and “No Man’s Land.”

That last set of arcs started in 1998 and took all of 1999 to resolve. “No Man’s Land” even played out in real time, chronicling Gotham City’s quake-ravaged 1999. It also provided a transition between one set of veteran Bat-writers (including Doug Moench, Alan Grant, and Chuck Dixon, each of whom had been with the books for at least seven years**) and the next. Initially, that next group included Rucka on Detective Comics, Devin Grayson on Batman: Gotham Knights (Shadow of the Bat’s replacement), and Larry Hama on Batman. Brubaker followed Hama, whose seven-issue stint is perhaps most memorable for worst-villain-ever candidate Orca. Her introductory arc -- which Chris Sims described as “the last story before Batman got good again [under] Ed Brubaker” -- took up three of those issues.

This was in contrast to Rucka’s excellent Detective Comics work (drawn with a sublimely minimalist style by Shawn Martinbrough), which introduced pivotal characters like Whisper A’Daire, Vesper Fairchild, Sasha Bordeaux, and the just-transferred-from-Metropolis Detective Crispus Allen. Brubaker’s approach complemented Rucka’s pretty well, and was certainly a nice change of pace after Hama’s more blunt storytelling. Both writers worked hard to make Gotham City feel authentic -- well, authentic for a habitat of well-financed urban vigilantes and the criminal psychotics they fought -- and like a place actual people could live and work.

Their efforts were helped by the familiarity which accompanies a shared universe’s established characters. Rucka and Brubaker created new characters for GC, but they also used Crispus Allen, stalwarts Reneé Montoya and Harvey Bullock, Commissioner Michael Akins (at the time, Jim Gordon had retired), Maggie Sawyer, and the psychic Josie MacDonald (created for a Detective Comics backup by Judd Winick and Cliff Chiang). Seeing a mix of characters with varying levels of GCPD experience helped give Gotham Central the feeling that generally, the Major Crimes Unit had been dealing with the Bat-family for longer than it would have liked. In 2003, that meant somewhere around ten years. As mentioned above, if Gotham Central were relaunched today, naturally it could include the same names and faces, but it might have to go farther to create such a convincing world-weary atmosphere.

In particular, Gotham Central benefited from the kind of fictional history which grows up organically from decades of prior comics. Occasionally, when fidelity to that history takes precedence over storytelling concerns, you get complaints that continuity is killing comics and/or driving away potential new readers. (Despite their longevity, I don’t remember the Grant/Moench/Dixon Bat-books of the ‘90s doing a whole lot of looking back.) Sometimes, though, that trivia can provide the details which bring a setting to life. The Rucka-written 52 and Checkmate (both of which followed GC) also grounded themselves pretty firmly in an “old,” established DC Universe.

Now, I don’t pretend to believe in one approach for all superhero books. The Bat-books of the ‘90s did pretty well with new villains (especially Bane), and Scott Snyder’s “Court of Owls” arc would probably look a lot different -- and be a lot more byzantine -- if it had to line up precisely with seventy years of Batman continuity. (This week’s Batman Incorporated #2 also goes a long way towards explaining how a ten-year-old Damian Wayne fits within a five-year Batman timeline.) There is a lot of history in the New 52, and a lot of dots to connect, but apart from the “historic” books like All-Star Western and Demon Knights, Snyder’s work on Batman and Swamp Thing, and Geoff Johns’ Green Lantern, much of it feels a mile wide and an inch deep. The New-52's backstory doesn’t appear to lean on existing stories as much as the old one did, which reinforces the perception -- good or bad -- that DC now sees its voluminous library as a storytelling liability.

That’s the publisher’s prerogative: if that’s what brings it more business, that’s what it’ll do. (I realize I’ve been arguing on behalf of a cult-favorite comic cancelled for six years.) Besides, it’s not like the only books Ed Brubaker knows how to write depend on retcons and shared-universe minutiae. I’m happy for him that he’s more free now to focus on his own creations.

Even so, whenever a publisher decides simply to cut itself off from its own fictional history -- regardless of how complicated that history may be -- it strikes me as short-sighted. In a market saturated with superheroes, where Batman stars in four monthly books and his allies star in four or five more, there can be so much “sameness” that anything too different might be too odd even to sample. However, we readers need that difference in order to avoid being beaten down intellectually. After a decade of flashy, gaudy superheroics, Gotham Central cast a critical, but respectful, eye on the public face of the Batman mythology; and the Bat-books were better for it.

Ed Brubaker probably won’t be writing for DC’s superhero line anytime soon, and (as with Chris Roberson) the New-52 books seem content to get along without him. At the risk of gross generalization, a certain air of superficiality still hangs over the New-52 books, which I think discourages unusual titles like Gotham Central. The Bat-books of the 1990s weren’t entirely similar, but I think some of the same high-concept thinking is at work across the New-52 generally. In 2003, Gotham Central was a thoughtful, introspective response to all that flash. I imagine it’ll be a while before the New-52 books look at themselves in such a way -- but this time, DC appears less willing to mine its own past.

++++++++++++++++++++++

* [Brubaker wrote Batman from 2000-02 (issues #582-87, 591-607) and Catwoman from 2002-05 (issues #1-37, plus an introductory 4-part backup feature in Detective Comics); and in 2003 wrote several issues of Detective itself (#s 777-82, 784-86), following Greg Rucka’s three-year run on the title.]

** [Chuck Dixon wrote some 87 issues of Detective Comics from May 1992's #644 through February 1999's #729. (During this time Dixon also wrote Robin, Nightwing, the pre-Brubaker volume of Catwoman, and Birds Of Prey, but I didn’t total those up.) In his second extended Bat-stint, Doug Moench wrote 79 issues of Batman, from Early July 1992's #481 through October 1998's #559. Alan Grant was even more of a constant, starting with Detective Comics #s 583-97 (February 1988-February 1989), #s 601-621 (June 1989-September 1990), and #s 641-42 (February-March 1992); plus 19 issues of Batman in 1991 and ‘92 (#455-66, 470-71, 474-6, and 479-80) and all 83 issues of Shadow of the Bat (1992-99). (Where appropriate, these totals include October 1994's “zero issues” and November 1998's “one million” issues, in case your math isn’t working out.)]