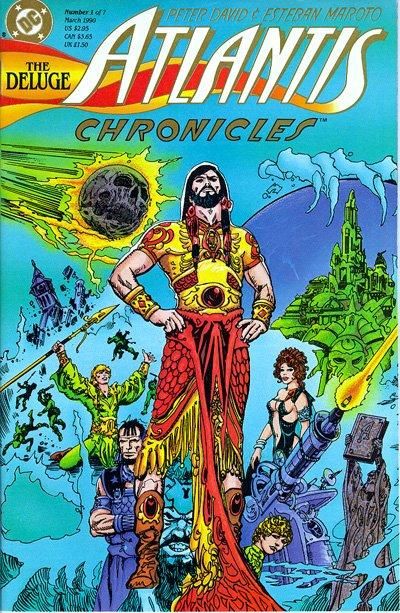

Last week’s big reorganization project is finished (for now) -- but by reintroducing me to Peter David and Esteban Maroto’s The Atlantis Chronicles, it has already paid off.

The Atlantis Chronicles was a seven-issue 1990 miniseries designed to give Aquaman a more “classically mythic” backstory. Like the Old Testament or your average Shakespearean tragedy, it is full of intrigue, violence, sinister motives, and secret affairs. Along the way it traces the history of twin cities Poseidonis and Tritonis from their sinking to Aquaman’s birth, explaining such things as marine mental telepathy, why the Tritonistas are mer-people, and when the Idyllists broke off into their own community. It was all in service to a PAD-written Aquaman regular series which ended up being delayed for a few years; and which, when it finally did appear, produced the cranky, hook-handed Aquaman of the ‘90s. Re-reading The Atlantis Chronicles reminded me that some noteworthy plot elements -- including an involuntary amputation -- foreshadowed similar events in the later series. Some characters from TAC also reappeared in David’s Aquaman, further connecting the two.

I enjoyed The Atlantis Chronicles on its own merits, but I couldn’t help but think how it would have been treated better in today’s marketplace. That, in turn, got me thinking about the roles various “historical” DC miniseries played (and might still play) in the building of their legends.

* * *

These kinds of miniseries aren’t that common, simply because the history they impart tends to come out in more run-of-the-mill superhero stories. The 1992 “Destroyer” arc revealed the secrets of Gotham City’s weird architecture while Batman raced to stop a mad bomber. (It also let DC incorporate the late Anton Furst’s movie-style designs into the comics’ Gotham.) The development of the Green Lantern Corps, from the Guardians’ homeworld of Maltus through the Manhunter revolt and up to the present, could be pieced together from factoids dropped in various issues. Krypton’s history was explored similarly throughout the Silver and Bronze Ages. However, with each bit of data serving a different story’s needs, pulling them together into their own coherent narrative might not be that easy.

In this respect, I’ve always been curious about what (for lack of a better term) I’ll call “the Superboy problem.” Regardless of incarnation, we treat Superman as if he only became “Superman” when he first performed some heroic public feat (likely involving Lois Lane) in Metropolis. This is understandable, because Superman’s debut marks the beginning of the current Age Of Superheroes, and it’s a renaissance for the heroic ideal, blah blah blah. That’s all fine.

Nevertheless, on the old Earth-1, Kal-El of Krypton first appeared to the public in his familiar red-and-blue costume as “Superboy,” a kid operating out of somewhere in the Midwest. From what I understand, there were a few other adult superheroes (and assorted heroic types) doing good deeds during this same “pre-Silver Age” period -- guys like Zatara and Captain Comet, and maybe the Challengers of the Unknown. Remember, on Earth-1 there was no Justice Society, and no significant Golden Age of superheroes, to give Superboy any context. His debut was probably more of a game-changer than, say, Captain Comet’s; but it’s not treated that way. For practical reasons -- i.e., because none of the other big Silver Age superheroes had significant teenage careers -- the Earth-1 Age of Superheroes kicked off in earnest with the first appearances of Batman, Wonder Woman, the Flash, Green Lantern, Aquaman, the Atom, et al. Superboy might have saved the world several times over before he could drive, drink, or vote, but those adventures are, in large part, separated pretty definitely from his Superman career.

Trying to bridge the gap was 1985's Superman: The Secret Years, a four-issue account of Clark Kent in college, written by Bob Rozakis and pencilled, as usual, by Curt Swan. It had the misfortune to come out right before Crisis On Infinite Earths, which meant it was only a valid part of Superman continuity for about a year and a half. Still, it did feature a couple of previously-untold skirmishes with Lex Luthor, a retelling of the Lori Lemaris story, and the introduction of Clark’s college roommate. If Superman were Ron Howard, Secret Years was like American Graffiti, providing a link between the child Opie and the young-adult Richie. Such a linkage is important, I think, because only by seeing one’s career as a whole can we evaluate it properly.

However, among history-minded Superman miniseries, Superman: The Secret Years may have been unique in focusing on the Man of Steel himself. Other miniseries looked to Superman’s ancestors and surroundings: 1979's World Of Krypton, 1997-98's The Kents, the one-shot Unauthorized Biography Of Lex Luthor, and 1988's John-Byrne-written triptych World Of Krypton, World Of Smallville, and World Of Metropolis. I never read the first Krypton miniseries, but I don’t think it had much impact on the regular monthly series. I know The Kents -- which was basically a Western with very loose connections to the Superman mythology -- didn’t really tie into the ongoing books. The Luthor book had some influence, which (thanks to Luthor’s “rediscovered” years in Smallville) may have been dulled; and naturally the Byrne-written books were designed to deepen what was at the time a brand-new continuity.

Because the “Byrne influence” isn’t as pronounced as it was in the ‘80s, or even the ‘90s, those World Of ... miniseries aren’t as relevant to today’s books. It’s therefore a little surprising to me that 2008's Superman: World Of Krypton paperback collected the 1988 miniseries (drawn by Mike Mignola -- hey, there’s a reason to collect it!) along with some pre-Crisis “World Of Krypton” backup stories. The Kents is also readily available from Amazon, so there are two paperbacks which, if you’re interested in current continuity, may be no more than curious footnotes.

And speaking of which, if a publisher wants to promote its current continuity, I guess there are two practical reasons to do an historical tie-in: either to set up said continuity, or to pull disparate data together into a coherent narrative. In the wake of Crisis On Infinite Earths, DC launched Secret Origins, dedicated entirely to the details of continuity, and particularly dedicated to those two types of stories. At the time it was a valuable resource for readers concerned about what Crisis had changed; and I think there are still a fair amount of such readers today. If the project doesn’t deal with current continuity in some way -- and, perhaps more importantly, if the publisher doesn’t treat it as controlling -- it’s just another superhero story. (Signs that The Atlantis Chronicles wasn’t initially promoted as the harbinger of Peter David’s Aquaman included house ads for issue #5, and that issue’s text recap pages.) It may be an exceptionally well-done superhero story, but it loses that historical cachet which presumably gives that sector of the audience a reason to read it.

In other words, it’s Superman: Birthright, which I liked quite a bit, and which I thought told a more cohesive Superman origin story than Byrne’s Man Of Steel; but which always had a shaky relationship with the then-current Superman books. Somewhat in the same boat, ironically enough, is the recently-concluded Superman: Secret Origin, Geoff Johns’ and Gary Frank’s six-issue overview of Clark’s childhood and early appearances in Metropolis. Since it came out after Johns had left the Superman titles, it struck me more as a victory lap than a setup for future storylines. Specifically, it showed Clark, as “Superboy,” meeting the Legion of Super-Heroes; and it retroactively established Lois’ father, Luthor, and Metallo as part of a military-industrial anti-Superman plot. Both of these plot elements first appeared during Johns’ tenure on Action Comics, although they could have come from his fellow Superman writers and editors. Secret Origin also reprised some themes from Birthright, including putting young Lex Luthor back in Smallville, and having Luthor’s Superman-driven paranoia fuel the climactic battle. There were other nods to post-Crisis continuity too (Kenny “Conduit” Braverman comes immediately to mind), but Secret Origin wasn’t exactly a synoptic overview of the current Superman origin story.

Indeed, for something like that you have to go back over thirty years, to 1980's three-issue Untold Legend Of The Batman. Written by Len Wein, the first issue was pencilled by John Byrne and inked by Jim Aparo, and the other two were drawn entirely by Aparo; so it looked fantastic and it read well too. Because the basic plot involved a mysterious mastermind out to destroy everything Batman held dear, the Dynamic Duo and Alfred ended up reminiscing as part of their detective work. This was during the period in Bat-history when gangster Lew Moxon ordered Joe Chill to murder the Waynes, and when a teenaged Bruce donned a familiar red-and-yellow costume to train with detective Harvey Harris. Thanks in large part to those stories, and others from the ‘40s and ‘50s which explained various Bat-minutiae, Wein wove a good bit of pre-existing material into his narrative, updating it appropriately for the ‘80s readership. It’s the kind of miniseries which gives the basic Batman setup a real sense of depth and scope. I hesitate to compare it to Grant Morrison’s recent Batman work, because Morrison dealt with those old stories more lyrically and abstractly, and was more concerned with establishing a new tone than setting old details in concrete.

(Not that the concrete setting of details is unimportant, mind you. My memories of ULOTB raised my expectations for Wein’s current historical miniseries, DC Universe Legacies, but eight issues in, I’m still not sure how I feel about it, mainly because I think he’s placed some events out of order. I’m sure a DCUL post will be forthcoming.)

Because 1993's The Golden Age added some disturbing new details to the Justice Society’s postwar history, it was eventually given the Elseworlds badge. Still, writer James Robinson incorporated some of TGA’s plot elements into his Starman series, which launched soon afterwards and which also featured regular “Times Past” flashback tales. The Golden Age is still readily available, and I think it may compare best with The Atlantis Chronicles in terms of influence on a subsequent regular series. We may never know whether an Atlantis Chronicles paperback would have helped the fortunes of Peter David’s Aquaman, but I believe The Golden Age and Starman were mutually beneficial.

Of course, Geoff Johns (and whoever writes Aquaman after him) is free to use whatever he wants from The Atlantis Chronicles as he reintroduces Aquaman to today’s readers. That in itself may be enough to get The Atlantis Chronicles back into print; but I have a feeling that if such a thing were going to happen, it would have happened already. As well, maybe The Atlantis Chronicles has become so identified with David’s run that subsequent writers haven’t wanted to deal with it.

I can’t leave this topic without noting a couple of recent historically-oriented storylines, namely Paul Levitz’ and Kevin Sharpe’s looks back at the early Legion of Super-Heroes in Adventure Comics and the terrific Chris Roberson/Jesus Merino Lord of Time two-parter in Superman/Batman. The former seems targeted to longtime Legion fans who can plug the particular stories into a Legion timeline which is no doubt familiar to them. I’m sure that is rewarding, because this week’s issue of Superman/Batman should fit quite neatly into DC’s books from, say, 1982. References to the Wild West and to Gordanian slavers place its “Bronze Age” sequence after both New Teen Titans #1 (November 1980) and Justice League of America #199 (February 1982), and the rest of the issue spans centuries. In both cases I’m sure the details are just Easter eggs, but what are Easter eggs for if not to make you happy?

Ultimately, then, I think these historical storylines are valid exercises to test the limits of superhero continuity. Can we learn anything from a character’s previously-unexplored period, as in Superman: The Secret Years? Would a project like Untold Legend Of The Batman produce a consistent, coherent narrative from disparate data points? Will an entirely new backstory, like that provided by The Atlantis Chronicles, entice new readers and satisfy existing ones? I am still waiting for the “synoptic Superman” origin -- or, better yet, a detailed look at the post-Infinite Crisis Wonder Woman -- to examine whether anything consistent remains from recent continuity changes. While strict fidelity to established continuity shouldn’t dictate the kinds of stories DC’s superhero line tells, a critical examination of that continuity can be both instructive and illuminating.