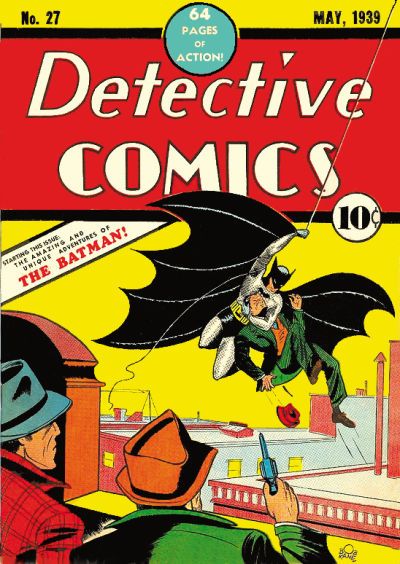

Not that I’d forgotten, but CSBG’s new 75 Greatest Batman Covers poll was just the latest reminder that this is Batman’s 75th anniversary year. According to Mike’s Amazing World of DC Comics, Detective Comics (Vol. 1) #27 hit newsstands on or about April 18, 1939, which means the celebrations don’t have to start right away.

Still, so far Batman’s 75th seems to be a rather low-key affair, at least as compared to Superman’s 75th last year. That anniversary included a special logo, a new movie, a few new ongoing series, a couple of celebratory collections (including one for Lois Lane, who shares the anniversary) and an animated tribute. Batman’s already gotten a giant-sized Detective (Vol. 2) #27, and the final Arkham Asylum video game is coming out. Additionally, before 2014 ends, we’ll probably see Ben Affleck in the new Batsuit, plus whatever Batman Eternal has in store. Beyond that, however, it seems like business as usual for the Dark Knight.

Fortunately, business has been pretty good for a while now, such that slapping an anniversary tag on the various Bat-offerings almost seems superfluous. By this point Batman practically is eternal -- but what does that really mean?

* * *

Batman’s success comes in no small part from his adaptability. In a sense, this goes back even to his conception, when Bill Finger’s improvements turned Bob Kane’s winged, red-suited character into a gray-and-black creature of the night. Naturally, the additions and expansions didn’t stop there. In “The Case of the Chemical Syndicate” there was just Batman, Commissioner Gordon and an array of white-collar figures embroiled in a murderous scheme. Bruce Wayne appeared only at the beginning and the end, and the origin wouldn’t be told for another six months. Girlfriend Julie Madison, the utility belt and Batarang, villains Doctor Death and the Monk, and early versions of the Batmobile and Batplane all got the spotlight before readers learned about the Wayne murders. Robin was the next big addition, coming at the end of Batman’s first year in April 1940's ’Tec #38.

Indeed, the Boy Wonder changed Batman comics irrevocably, turning the headliner from a grim avenger into a more fraternal-paternal figure; but the comics endured. Similarly, in the 1950s, when outside pressures forced the Dynamic Duo away from grotesque gangsters and into more fantastic adventures, the comics kept going -- and even after that style had run its course, it helped inform the insanely popular television series. The 1960s generally put Batman through all manner of different approaches, from a ‘50s sci-fi hangover to the relatively sober “New Look,” and from TV-fueled wackiness to, ultimately, Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’ Darknight Detective.

Throughout those periods, and indeed into the 1970s and ‘80s, there were times when Batman wasn’t all that popular. The “Batman Family” expansion of the 1950s -- it included Batwoman, Bat-Girl and Ace the Bat-Hound -- deliberately mirrored the introductions of Krypto and Supergirl in the better-selling Superman titles. Later, Julius Schwartz, John Broome and Carmine Infantino created the New Look to stave off low sales (which, in those days, meant fewer than 200,000 copies per month). Detective itself was almost canceled in the mid-1970s, before someone realized it was the book the company was named after -- so they instead canceled Batman Family and moved its features into ’Tec. Following the early-‘80s success of New Teen Titans (which, of course, featured Robin heavily), Batman got his own team book, whose Titans-esque roster also mixed established and new characters.

Those down periods ended in 1985, with Frank Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley’s The Dark Knight Returns. Its four issues established Batman firmly as a solitary, misanthropic loner, beholden to no one but himself and the memory of his murdered parents -- and, by the way, more than a match for that stooge Superman. It was probably the most extreme portrayal of Batman to that point, and the comics didn’t really try to go as far. Jim Starlin’s run as writer (which ended with Jason Todd’s death and featured M.D. Bright and Jim Aparo as artists) probably came the closest. Compare it, though, with Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle’s energetic work, or writer Marv Wolfman’s not-so-subtle attempts to lighten up Batman (including introducing Tim Drake) following Starlin’s tenure.

Guided by editor Denny O’Neil and writers like Grant, Doug Moench and Chuck Dixon, the Bat-books reached a sort of equilibrium in the 1990s, with Batman as the gloomy center of a growing circle of better-adjusted associates. That was the start of the Bat-franchise we know today, which supports not just Detective and Batman but spinoffs for many of those ancillary characters. Although it’s being pared back, the line of Bat-books still makes up between 20 and 25 percent of the New 52's ongoing series. That speaks to the character’s continuing appeal, and specifically to his long coattails (capetails?).

Of course, the ‘90s also saw the fruit of 1989's Tim Burton-directed Batman movie. Besides its three sequels, Batman also led to a long-running animated series that itself spawned the DC Animated Universe. Even the flop that was Batman and Robin allowed Christopher Nolan and company to launch what became the “Dark Knight Trilogy.” Now Nolan and screenwriter David Goyer are responsible for the latest round of Superman films, and by extension the putative “DC Movie Universe.” Moreover, the Arrow TV series seems indebted heavily to Nolan and Goyer’s style (just as the ‘90s Flash series aped Burton’s), and it too hopes The Flash will have spinoff success.

In short, it’s not difficult to see how DC might try to use a successful Bat-project as a template for jump-starting something else. Not only is Batman popular on his own, but certain elements of style and setting are apparently comparably popular. There’s also the appeal of characters who don’t have Batman’s emotional issues, but are still perfectly capable of doing Batman-like deeds. (This last applies especially to the Green Lantern books, which may be part of why that line is expanding.)

More to the point, though, it must be tempting to look at all those Bat-successes -- from Miller forward -- solely as the product of a consistently “serious” or “realistic” approach, and want to apply that to any number of tonally-different characters. After all, Batman inhabits the world that’s closest to our own, where there are no super-powers and no Kryptons, Themysciras, Atlantises or Oas to faciliate them. You don’t have to believe a man can fly, just that he can move convincingly in body armor. From there it’s not much of a stretch to hold those more fantastic characters to a similarly practical standard of believability.

While this hasn’t done away with the traditional explanations for superpowers -- yellow-sun rays, gifts from the gods, lightning and chemicals -- it’s more problematic when comparing Batman’s psychological elements to those of his colleagues. There are various degrees of tragedy in the backgrounds of many DC characters, from Krypton’s destruction and the Amazons’ subjugation to Adam Strange being separated from either Earth or his significant other. However, that doesn’t mean every DC character needs some melancholy. Nevertheless, Hal Jordan and Barry Allen must now deal with fallout from a parent’s untimely death, and the Amazons are currently a lot more bloodthirsty. Grim and gritty may work for Batman, but it doesn’t work for everyone. Even “A Death in the Family” was supposed to produce a more mellow Batman and a less-combative Robin, either through a recovered Jason or his replacement.

And that brings up another critical element in Batman’s success: the audience. Only a fraction of Batman’s readership voted in “DITF’s” fateful poll, and the margin was razor-thin -- but it was still the public speaking. The public also rejected the jokey Batman and Robin and embraced Batman Begins eight years later. DC can justify grim and gritty, because even after all this time, it still works -- and if it doesn’t work on some characters, it still works on Batman, and that may be enough.

To be sure, arguing against grim and gritty is hardly new. However, as Batman turns 75 -- and in two years, when The Dark Knight Returns reaches 30 -- the reasons for his continued success seem to come back to Frank Miller’s paradigm shift. Miller gave the world a Batman as he could be, and the world ate it up, even as the comics soon backed off.

Regardless, while Miller reduced Batman to some very primal elements, The Dark Knight Returns also reacted to almost 20 years’ worth of Batman ‘66's biff-bang-pow imagery, as well as (to a lesser extent) the driven-but-sociable figure from the then-current comics. The most rebellious thing the Batman of the 1980s did was quit the Justice League and form a team that included Halo and Geo-Force. His adventures were serialized twice a month in Batman and Detective, and he juggled the affections of Catwoman, Vicki Vale, and Alfred’s daughter Julia. Compared to those comics, The Dark Knight Returns was a blast of raw pulp energy, refocusing Batman’s mission as the only possible marriage of childhood tragedy and bat-winged inspiration.

Still, not even that went back to the very beginnings of Batman. As those first six months of existence demonstrated, before ’Tec #33 revealed his origins and ’Tec #38 revisited them (in the context of introducing Robin), Batman was all about style, not psychology. After “Chemical Syndicate,” he fought mad scientists, vampires and werewolves, while inventing new weapons to help his solitary crusade. It didn’t matter why, because at that time the readers didn’t know why -- and it didn’t matter for decades afterward, because style and adventure remained the emphases. Even something as classically-dark as the Joker’s origin (in 1951's Detective #168) was part of a goofy story about Batman becoming a college professor -- but that was perfectly in keeping with the style at the time. Whether drawn by Bob Kane, Dick Sprang, Carmine Infantino, Marshall Rogers, Jim Aparo or Greg Capullo, this notion of a Bat-style unifies the books across the decades.

For me, devotion to that style (however portrayed) has enabled Batman to survive and thrive. Accordingly, instead of any single tribute (or set thereof), the best way to celebrate his 75th anniversary might well be to recognize that his success isn’t so easily duplicated. Rather, as the world around him has changed, Batman has adapted. Miller’s force of nature casts a long shadow, but in the past several years, writers like Grant Morrison and Scott Snyder have incorporated elements that he implicitly rejected, in order to fashion a more nuanced, compelling, and (indeed) timeless character.

That’s why it almost seems redundant to make a big deal out of Batman’s anniversary. By this point Batman has become so pervasive that a parody version can steal scenes in The Lego Movie. Nobody needs a reason to put out a new set of Batman comics, a new video game, a new TV series or (because you know they’re coming) new movies. It’s just Batman, you know? So by all means, celebrate however you want -- I’ll probably do something in this space before too long -- but keep in mind that Batman’s perpetual appeal is the product of countless professionals, each of whom were no doubt inspired by what “The Case of the Chemical Syndicate” set forth so stylishly, and so minimally.