Different interpretations aren’t a problem for Batman, who’s taken on everything from Adam West and Bat-Mite to Frank Miller and Kelley Jones. Same goes for Wonder Woman (the original Marston/Peter crusader, Gail Simone’s steely warrior, and the current Brian Azzarello/Cliff Chiang monster-killer) and Aquaman (Ramona Fradon, Jim Aparo, Peter David). Likewise, each new Robin, Flash and Green Lantern puts a different spin on the core concept.

And yet, among all the elasticity of DC’s superhero line, Superman stands out as somewhat inflexible. More and more I am becoming convinced that there can be only one valid interpretation of Superman. That interpretation might work for a variety of storytelling styles, but the character at its core must fundamentally be the same.

For starters, let’s run down the list of everything the main-line Superman -- the character, not necessarily the stories in which he appears -- is not. Superman is not arrogant, manipulative, cruel, boastful ... well, you get the idea. I’m not rewording 1 Corinthians 13 here, but that’s not a bad place to start when thinking about Superman’s motivations. “Love never fails,” begins the New International Version translation of verse 8, and that’s pretty much the idealist at the heart of Superman, isn’t it? Superman never fails, not because of invulnerability or super-strength or heat vision, but because his indomitable faith in the goodness of humanity keeps him going.

That’s why the periodic images of a crying Superman are so incongruous. While the character may be seen as hopelessly naïve (and therefore more prone to disappointment than some of his hardened-by-tragedy colleagues), the real shock of Superman distraught comes from recognizing that apparently not even he has any optimism left. Put more simply, Crying Superman confirms that we are as bad off (or perhaps just “as bad”) as we suspected.

To be sure, such nihilism may fit whatever DC’s trying to sell. In the summer of 1985, mourning Supergirl’s death helped readers understand both the scope and the stakes of Crisis on Infinite Earths. In 2007, weeping on Wonder Woman’s shoulder in the infamous Countdown teaser similarly alerted readers that things could still get worse. Paradoxically, though, the farther DC gets from a resonant Superman characterization, the less value such sentiment has. The cover of Crisis #7 worked in large part because Superman was the very symbol of DC’s constancy. (Its homage to Jean Grey’s sacrifice in Uncanny X-Men #136 -- which at the time was next to Gwen Stacy’s in terms of an ongoing character’s game-changing, irrevocable death -- helped drive home the point.)

Indeed, DC has played with Superman’s status quo for decades. January 1971's Superman #233 (by Denny O'Neil, Curt Swan, and Murphy Anderson) -- in which a freak nuclear accident rendered inert all the Kryptonite which had thus far made it to Earth -- both increased Superman’s effectiveness and undermined his trustworthiness. As Morgan Edge put it, “I don’t trust anyone who can’t be stopped!”

Accordingly, trust is at the heart of Superman’s character. Just as his lack of a mask helps the public trust him, so does he trust the values the Kents taught him. Rather than being the emissary of a more ethically-advanced culture, Superman is a reflection of the best in human morality. If I were more of a moralist, I might even speculate that those who find him unrelatable blame him for not mirroring their own ethical drifts.

However, I am not so inclined, because the stories themselves are often the problem. Both Smallville and Superman: Earth One focused on a Kal-El growing into an heroic ideal, and therefore both allowed him to be self-centered in various ways. Smallville did it practically by design (as explained hilariously by ComicsAlliance’s two-headed season-long evisceration), and I have to assume that Earth One did it similarly to show a Superman who hasn’t quite arrived.

(Actually, in light of Earth One author J. Michael Straczynski’s fractured take on the grownup Superman, we might reasonably be concerned about his development. “Grounded,” the Superman storyline Straczynski started before leaving the book for the Earth One sequel, wasn’t received all that well, in part because it opened with a couple of tough-love moments. One had Superman try to call a suicidal jumper’s bluff, and another had him merely identify an elderly man’s imminent heart problems without, say, rushing him to the hospital. Both have been compared unfavorably to more persuasive Superman portrayals, including Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely in All Star Superman and Garth Ennis and John McCrea in a Hitman guest-shot. Straczynski’s Superman is willing to help, and I sort of liked the jumper scene, but at the very least there’s something a little hinky about his methods.)

For that matter, the first two Christopher Reeve movies had Supes follow his own interests. At the emotional climax of 1978's Superman, the Man of Steel has single-handedly saved California from falling into the ocean. Among other things, he’s shored up the San Andreas Fault, repaired the Golden Gate Bridge, dammed (I so wanted to say “changed the course of”) a runaway river, and prevented at least one trainwreck. When he realizes that all his efforts failed to save -- and maybe even prevented him from saving -- Lois, he races back through time to pick up the spare.* Likewise, renouncing his powers in Superman II also allows him to be with Lois unencumbered by superheroic obligations, even if he does so without a backup plan for safely leaving the Arctic. We can rationalize both: the first movie has Supes choose between Jor-El’s abstract edict and Jonathan Kent’s intuition, while in the second Supes may think there are no more super-menaces to thwart. Regardless, even allowing for inexperience we expect Superman to be a bit more selfless. The original King James Version of 1 Corinthians 13 referred to “charity,” not “love,” and what is Superman if not charitable?

In this respect the New-52 iteration is making progress. The socially-conscious Superman of Grant Morrison and Rags Morales’ five-years-ago Action Comics is young and cocky, but that attitude takes a back seat to his larger mission. It’s been harder to get a handle on the present-day Superman book, because that title has been more concerned with big action sequences and alien invasions. Specifically, Superman Vol. 3 has consistently featured villains trying to convince Kal-El he should be ruling the puny humans, yadda yadda yadda, only to be met inevitably with Superman’s emphatic refusal. As long as there are Superman stories there will be this plot, but its perpetual variations would be easier to take if they came amidst fresher attempts. And yes, an “old-fashioned” portrayal of Superman which emphasizes the effectiveness of his ethics** would be fresher than the slightly-above-average material coming out of Superman and Justice League. (I’m still good with Morrison, Morales, and the occasional guest artist in Action.)

To be clear, I don’t want Supes monologuing constantly about My Foster Parents’ Morals. Actually, I imagine that would undermine the effectiveness of his adherence to them. We shouldn’t have to be told he’s trying to do the right thing, because it should be self-evident. “Superman” is what happens when our ability to do good approaches our capacity for doing good, such that we see something when he doesn’t live up to that potential.

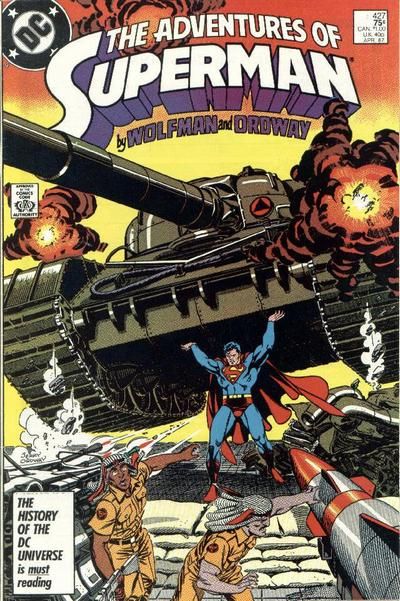

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster had Supes intervene in all manner of conflicts, from beating up an abusive husband to heading off a war. Marv Wolfman and Jerry Ordway tapped into that proactive streak in their 1986-87 Adventures of Superman run, by having Superman destroy the fictional Qurac’s military after it sponsored a terrorist attack on Metropolis. That arc balanced the visceral appeal of super-powered destruction against a healthy dose of “has Superman gone too far?” It also featured The Circle, a hidden super-powered society trying to convince Supes he should join them and rule the humans, but at least that wasn’t the story’s focus.

In a larger sense Superman’s reliance on personal ethics reminds me of Star Trek’s Prime Directive, or even the two sides of the Force. The Superman books could do worse than emulating Trek or Star Wars, because clearly neither of them had any problems working lots of cosmically-significant carnage into their morality plays. In particular, Star Trek’s famously sunny outlook comes from the same sort of this-is-who-we-should-be attitude. Providentially, James T. Kirk and Ma and Pa Kent all share a Midwestern upbringing, albeit a few centuries apart. Besides, even if late-period Trek got a little dark at times, our heroes were still conflicted about their choices. Rest assured, if a Superman story compares favorably to good Star Trek, it’s doing something right.

Nevertheless, you don’t get there without higher standards. Although ten months into the New 52 still leaves some time, the window won’t be open forever. It’s not enough for Superman to turn down hollow partnerships with alien conquerors, and I’m not content with all the ambition being concentrated in Action Comics. We may have moved beyond Weepy Supes, and the “who wants some?” attitude from early Justice League may be five years in the past, but let’s be definite about retiring those tropes. There are plenty of opportunities for Superman to embody the Kents’ lessons in matters big and small, and his current handlers should offer no less. You want comics for adults, DC? Put Superman in situations where he has to act like one, and show us why he’s the heroic ideal.

+++++++++++++++++

* [Yes, my interpretation of flying-real-fast-in-the-wrong-direction was that it allowed Supes to be in two places at once: saving Ms. Teschmacher’s mom and the rest of New Jersey while simultaneously diverting the West Coast-bound missile. This is clearly at odds with the movie’s footage-in-reverse depiction, but I can live with that.]

** [Not to mention its alliterative aspects....]