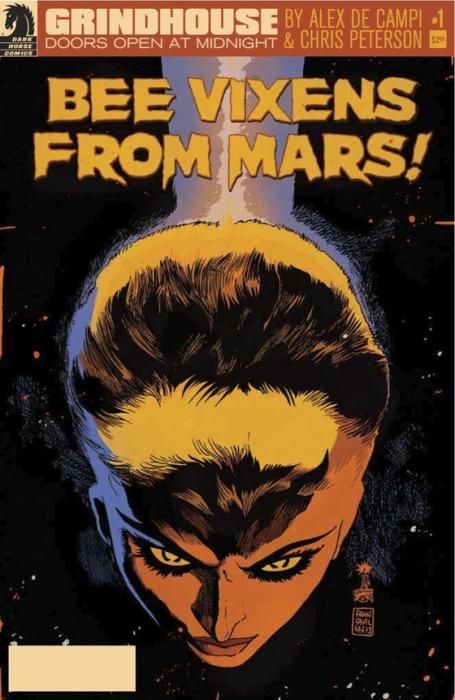

From the grindhouse homages of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez to the surprise popularity of B-movies like "Sharknado," it's fair to say that schlock storytelling has found an audience again. Alex de Campi's new Dark Horse series "Grindhouse: Doors Open at Midnight" attempts to bring that exploitation aesthetic to comics, with artist Chris Peterson drawing the first arc, "Bee Vixens from Mars".

The title more or less says everything you need to know about the story. It's a classically-structured monster movie where young people get torn apart while the authorities get picked off investigating their disappearances. Meanwhile, one lone cop -- in this case, the silver-haired, eyepatch-wearing, shotgun-toting Garcia -- attempts to bring the reign of terror to an end single-handedly.

As you'd expect, the grindhouse aesthetic is completely up-front. It's all gore, sex and explosions. That said, Peterson does do better with the moments of over-the-top horror than with the moments of exploitative sexiness. Perhaps the problem is that comics are already over-exploitative when it comes to women, but here they seem cartoonish rather than titillating, which means the book loses its aesthetic. You could even argue that it doesn't go far enough -- there's no actual nudity, despite some pretty graphic gore.

Although it generally makes concise use of the page, there are times when the book's fast-cut style works against the storytelling. Some panel and page transitions are hard to pin down, which brings the narrative to a halt at odds with the intended pace. Arguably, indecipherable transitions are an authentic trait of grindhouse cinema, but while you can get away with that in film where viewers can simply ride the confusion out, comics allow readers to stop completely if there's something they don't understand -- something which happens a little too often in this issue.

For the most part, though, it's a fun read, and it's certainly enjoyable to see something a little different. In an era when creator-owned comics often aiming to be as literary, dense and plot-driven possible, de Campi and her collaborators have gone in the opposite direction, reminding us that there's room in the industry for all forms of story, even the ones that start with a title and work backwards. It could backfire -- there's definitely a sense that it's preaching to fans of the genre, rather than finding a new audience for it -- but broadly speaking the nostalgia is the driving force, rather than the point, and in the end it's hard not to get caught up in the enthusiasm.